Preview text:

ASAIO Journal 2017 Clinical Cardiovascular

Multi-Sense CardioPatch: A Wearable Patch for Remote

Monitoring of Electro-Mechanical Cardiac Activity

EMANUELA MARCELLI,* ALESSANDRO CAPUCCI,† GABRIELE MINARDI,* AND LAURA CERCENELLI*

This study describes the conceptual design and the first proto-

Heart sound (HS) is an acoustic signal that results from vibra-

type implementation of the Multi-Sense CardioPatch, a wear-

tions created by closure of heart valves, mainly the first heart

able multi-sensor patch for remote heart monitoring aimed

sound (S1) when the atrioventricular valves close at the begin-

at providing a more detailed and comprehensive heart status

ning of systole, and the second heart sound (S2) when the aor-

diagnostics. The system integrates multiple sensors in a single

tic valve and pulmonary valve close at the end of systole. HS

patch for detection of both electrical (electrocardiogram,

signal is a well-known expression of cardiac mechanics, since

ECG) and mechanical (heart sounds, HS) cardiac activity, in

the amplitude of S1 reflects cardiac contractility,10–12 while dia-

addition to physical activity (PA). The prototypal system also

stolic pressure affects the amplitude of S2.13 HS signal is tradi-

comprises a microcontroller board with a radio communica-

tionally recorded using stethoscopes and phonocardiographs,

tion unit and it is powered by a Li-Ion rechargeable battery.

even if in recent years also accelerometers applied on the chest

Results from preliminary evaluations on healthy subjects have have been used.14–16

shown that the prototype can successfully measure electro-

We report the conceptual design and the assembly of a first

mechanical cardiac activity, providing useful cardiac indexes.

proof-of-concept prototype of a wearable multi-sensor patch

The system has potential to improve remote monitoring of

(Multi-Sense CardioPatch) that provides the remote monitoring

cardiac function in chronically diseased patients undergoing

of electro-mechanical cardiac activity. Compared with the patch

home-based cardiac rehabilitation programs. ASAIO Journal

systems already available on the market for cardiac monitor- 2017; 63:73–79.

ing, the Multi-Sense CardioPatch includes a sensor for record-

ing transthoracic cardiac vibrations related to HS (HS sensor),

Key Words: wearable, patch, electrocardiogram, heart

together with more standard sensors for electrical cardiac activity

sounds, accelerometer, sensor R

(ECG sensor) and physical activity level (PA sensor). The idea is to

ecent advances in sensor technology, microelectronics,

provide a wearable system for a more detailed and comprehen-

sive heart status diagnostics in patients undergoing home-based

cardiac rehabilitation programs, thanks to the simultaneous

telecommunication and data analysis techniques have enabled

detection of both electrical and vibromechanical cardiac activity.

the development and spread of wearable systems for patients’

remote monitoring.1 An emerging area is application of wear-

able sensors in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. Methods 2,3 The current

capabilities of wearable systems include physiologic sensing and motion sensing. Overview of the System

1,4–6 Physiologic measures mainly com-

prise heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, blood oxygen

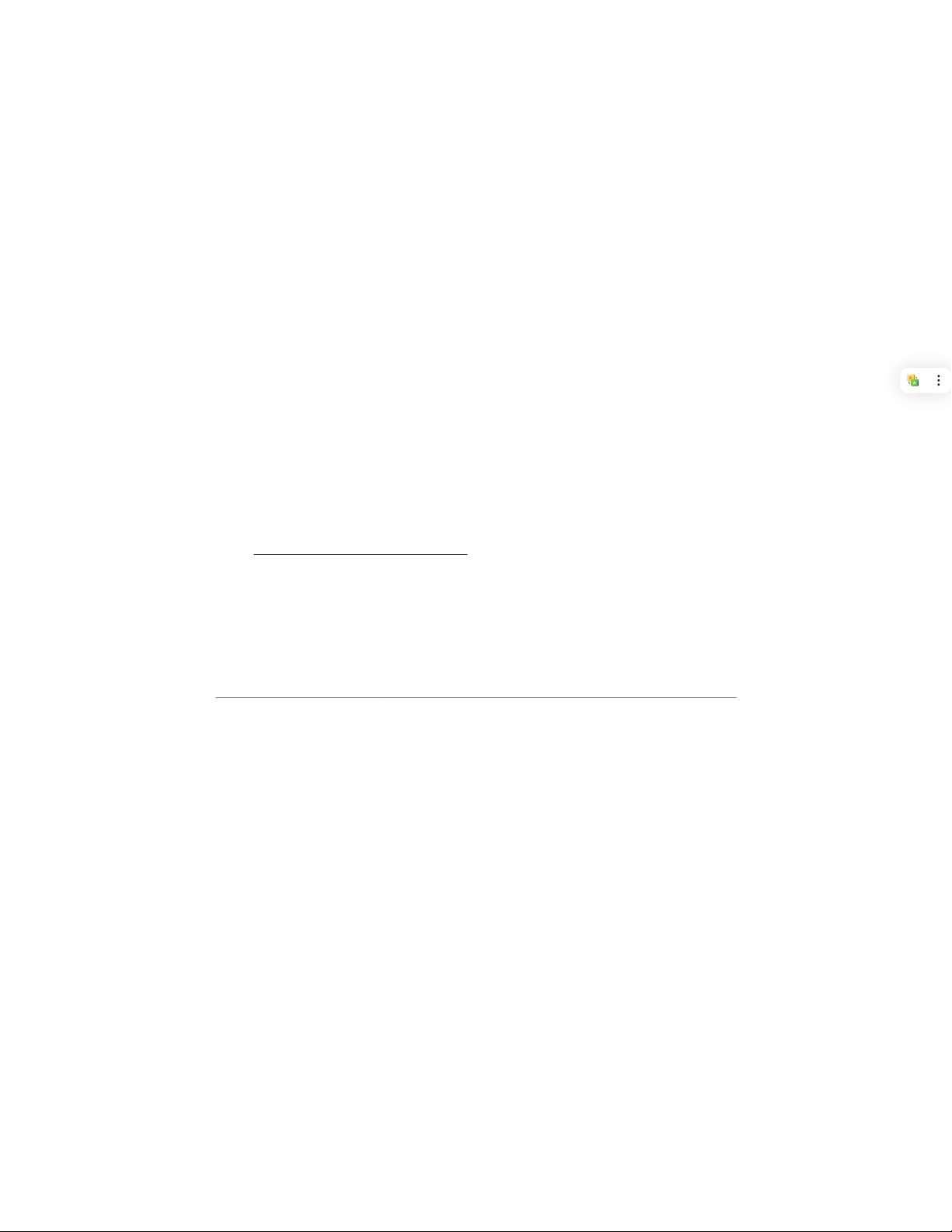

The Multi-Sense CardioPatch is a prototypal patch to be

saturation, and body temperature.6

applied on the chest, which comprises sensors and electron-

In the last years, a lot of work has been done about wearable

ics encapsulated in a flexible biocompatible silicon housing to

devices for remote monitoring of cardiopulmonary activity and

protect them from sweat and moisture. It is composed of two

many systems are now commercially available.7–9

parts: the main body and the small appendage (Figure 1A). The

All these systems have been mainly designed for continuous

main body is a silicon case (108 mm × 55 mm × 14 mm), which

monitoring of arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation, as well

includes a standard module for ECG recording, a tri-axial

as patient falls that may be associated with arrhythmias; there-

MEMS accelerometer for PA recording, a radio communication

fore, they rely on electrocardiogram (ECG) sensors to monitor

unit (Bluetooth module), and all the electronics (microcon-

the electrical cardiac activity and on a tri-axial accelerometer

troller, conditioning circuits, battery). Two side wings protrud-

to record activity level and body position.

ing from the main body include two metal snaps for standard

disposable ECG electrodes (Figure 1B).

The appendage is a small silicon case (23 mm ×10 mm × 8 mm)

From the *Experimental Diagnostic and Specialty Medicine Depart-

comprising a miniature piezoelectric accelerometer for HS sens-

ment, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy; and †U.O.C. Cardiologia

ing (HS sensor) and a third metal snap for the reference ECG elec-

Clinica, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy.

trode (Figure 1A). The appendage allows to adjust the position of

Submitted for consideration February 2016; accepted for publica-

tion in revised form September 2016.

the piezoelectric accelerometer on the chest to detect the highest

Disclosures: The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

HS signal. The flexible silicon material used for both the main

Correspondence: Laura Cercenelli, Università di Bologna, Dip. Medic-

body and the small appendage allows a good adaptation of the

ina Specialistica, Diagnostica e Sperimentale, c/o Sezione Tecnologie

patch to the chest’s shape. Adhesion to the thorax is ensured by

Biomediche, Policlinico S. Orsola Malpighi, Via Massarenti 9 (pal.17 – 2°

three standard adhesive button electrodes used for ECG recording.

piano), 40138 Bologna, Italy. Email: laura.cercenelli@unibo.it. Copyright © 2016 by the ASAIO

Data from HS, ECG, and PA sensors are preliminarily pro-

cessed (sampling and preliminary signal conditioning) by the

DOI: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000446 73

Copyright © American Society of Artificial Internal Organs. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 74 MARCELLI

Figure 1. Multi-Sense CardioPatch prototype (A) and its explosion view (B): 1. cover of the main body; 2. “wings” including ECG electrodes;

3. ECG module; 4. ECG electrodes; 5. appendage including HS sensor; 6. amplifier module for HS sensor; 7. Bluetooth module; 8. microcon-

troller; 9. tri-axial accelerometer for PA sensing; 10. battery. (C) Cantilever accelerometer used for HS sensor.

microcontroller, then sent via Bluetooth connection to a note-

data provided by the sensors included in the patch. Data sav-

book for real-time display and further signal processing.

ing can be controlled by soft keys on the GUI.

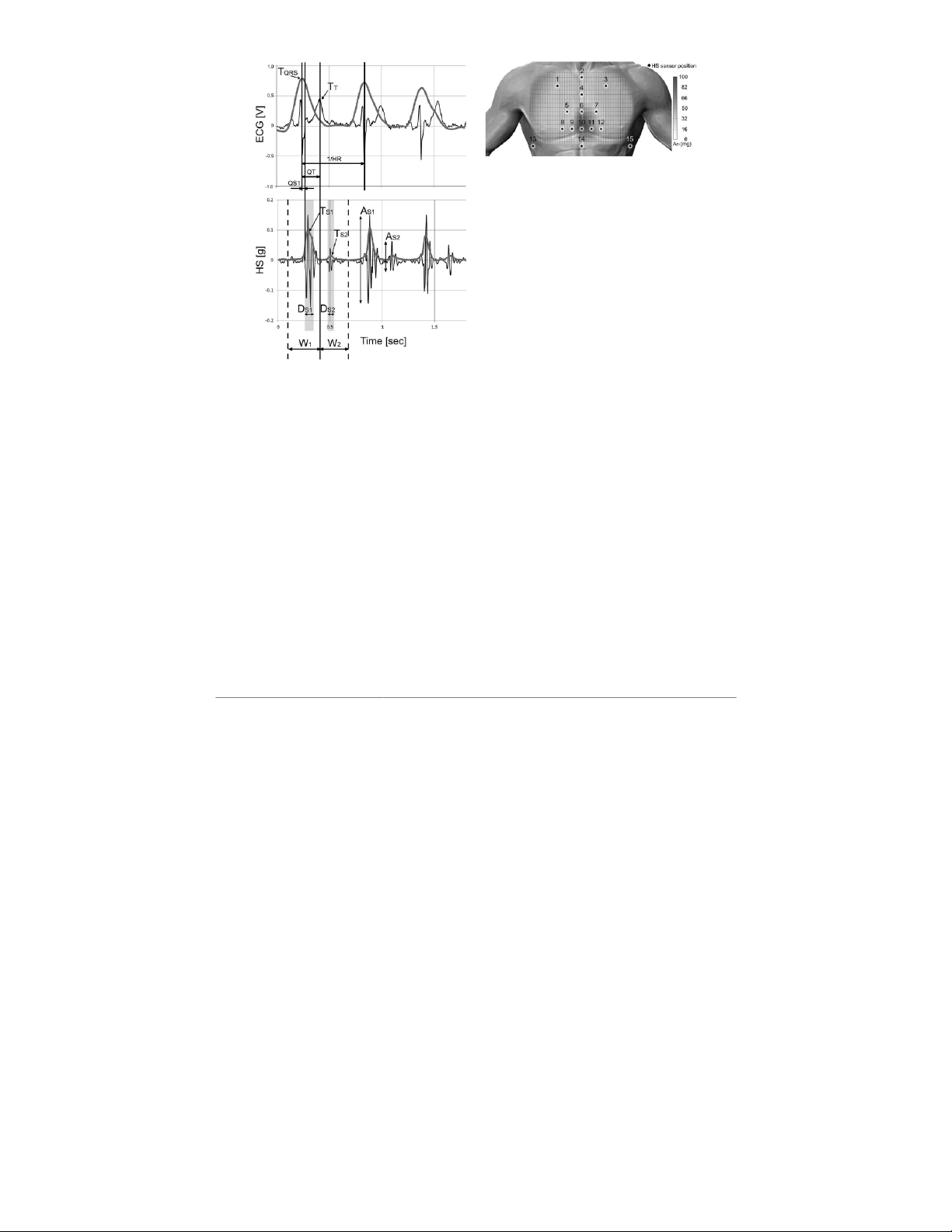

Electrocardiogram processing. A band-pass filter (10–30 Hardware

Hz) is applied to the acquired ECG signal to isolate the pre-

dominant QRS components and to attenuate the low frequen-

Sensors. The ECG sensor is a custom design composed of

cies of P and T waves, as well as to remove the baseline drift

1-lead recording provided by the two disposable ECG elec-

and the power line interference. The filtered signal is differ-

trodes included in the side wings of the main body of the patch

entiated and squared to emphasize the QRS high-frequency

and the third reference electrode in the appendage, coupled to a

components and then integrated (by low-pass filtering, cutoff

signal conditioning module (gain 200, bandwidth 0.1–100 Hz).

frequency of 3 Hz) to obtain the processed ECG waveform re-

The HS sensor is a piezoelectric cantilever accelerometer

ported in Figure 2 ( upper panel, grey bold line). A peak de-

(285–784 M641, Sensor Technology, Collingwood, ON, Can-

tector algorithm, based on a dynamic threshold, finds R-peaks

ada), with sensitivity of 80 mV/g, which detects the transthoracic

in the processed ECG waveform and the corresponding times

propagation of cardiac vibrations due to HS (Figure 1C). The

(TQRS), thus providing R–R intervals and heart rate (HR).

sensor, coupled to a transistor and a signal amplifier module

To detect T wave, a band-pass filter (0.5–30 Hz) is applied

(gain 200, bandwidth 5–155 Hz), is included in the appendage.

to the acquired ECG signal. Then, T-peak is searched within a

The PA sensor is a tri-axial MEMS accelerometer (ADXL335,

window that starts at TQRS and ends after a period equal to QT

Analog Devices, Norwood, MA) with a detection range of ± 3 g, interval estimated by using the Bazett’s formula, Equation 1.17

sensitivity of 500 mV/g, bandwidth 0–45 Hz.

Electronics and wireless communication. A microcon- =3.5

troller board (Arduino Pro Mini 328-5V/16MHz, Sparkfun, QT HR (1)

Niwot, CO) is used to sample the data collected by ECG, HS,

and PA sensors and to send them to a notebook via a Bluetooth

module (RN42, Roving Networks, o L s Gatos, CA) with baud

For P wave detection, the software estimates a dynamic tem-

poral window (P wave window) that starts at t = (T

rate 115200. The prototypal patch is powered by a Li-Ion re- QRS − 20% of

cardiac cycle duration) and ends at t = T

chargeable battery with 1,000 mAh capacity. QRS.

Heart sound processing. HS processing is strictly related to

ECG processing (Figure 2). The acquired HS signal is prelimi-

Software and Data Processing

nary differentiated, squared, and low-pass filtered (cutoff fre-

Graphical user interface. A dedicated program and graphi-

quency 10 Hz). Two searching windows for S1 and S2 analysis

cal user interface (GUI) were developed in ab L VIEW (National

are selected on the basis of the identified QRS complex, T wave,

Instruments, Austin, TX) to acquire, process, and display the

and P wave window: S1 is searched within a temporal window

Copyright © American Society of Artificial Internal Organs. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

WEARABLE PATCH FOR ELECTRO-MECHANICAL CARDIAC MONITORING 75

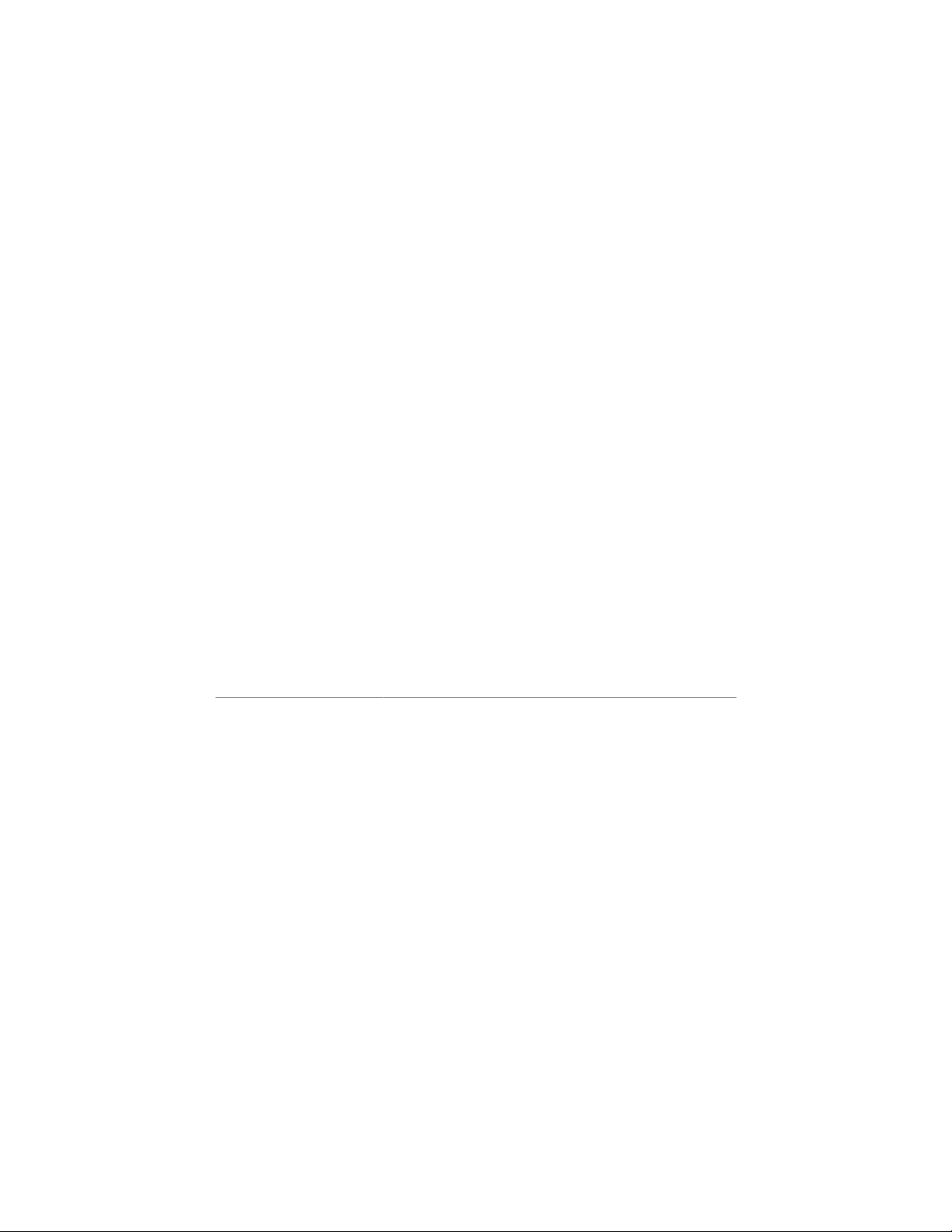

Figure 3. Topographic mapping of the thorax for S1 detection

(results from averaging AS1 data from 19 subjects).

categorized as motion conditions according to a preliminary

calibration procedure where several basic static and dynamic

body motions (e.g., stretches, walking, running, falls) are carried

out by a subject wearing the Multi-Sense CardioPatch.

Cardiac indexes. The implemented data analysis provides

indexes of both electrical (HR, QT interval) and mechanical

(AS1, AS2, DS1, DS2) cardiac activity. Additionally, by combining

simultaneous recordings of ECG and HS signals, cardiac time in-

tervals related to the electro-mechanical cardiac activity can be

derived. An interesting index that the implemented data analysis

calculates is QS1,18,19 i.e., the time interval from the onset of

QRS complex to the beginning of S1, as reported in Equation 2. QS = S S Q 1 RS 2 ( ) T- D / - T (2) 1 1

QS1 is the major component of the pre-ejection period

(PEP), which is a commonly used index of myocardial con-

Figure 2. Example of ECG, HS recordings (black lines), and the

tractility and sympathetic control of the heart.18,19 It has been

corresponding processed waveforms (grey bold lines). AS1: esti-

widely demonstrated that in heart failure patients, because of

mated S1 amplitude; AS2: estimated S2 amplitude; DS1: estimated

systolic dysfunction, there is a relevant prolongation of QS1

S1 duration; DS2: estimated S2 duration; HR: heart rate; QS1: inter-

val from onset of QRS to S1; QT: time interval between TQRS and

interval, as well as a reduction of left ventricular ejection.18,19

TT; TQRS: time of R-peak; TT: time of T-peak; TS1: time of S1-peak;

TS2: time of S2-peak; W1: searching window for S1; W2: searching In Vivo Evaluation window for S2.

We evaluated the Multi-Sense CardioPatch on 19 healthy vol-

(W1) from the start of P wave window to the time of T-peak (TT),

unteers. Preliminary tests were performed to evaluate the opti-

while S2 is searched within a temporal window (W2) from TT to

mal HS sensor position on the chest (“Positioning tests”) and to

the following start of P wave window (Figure 2).

compare, in three different body types, the HS sensor recordings

Amplitudes (AS1, AS2) and durations (DS1, DS2) of the two most

with a phonocardiography (PCG) signal (“Comparative tests”).

relevant HS components (S1, S2) are calculated: 1) a peak detec-

Finally, the 19 volunteers underwent a step-climbing exercise

tor algorithm is applied to the processed HS signal (grey bold

and their electro-mechanical cardiac activity was monitored

line in bottom panel of Figure 2) to find peaks within W1 and

with the Multi-Sense CardioPatch at the maximum workload

W2; 2) DS1 (DS2) is calculated as the time interval between the

condition and during recovery after exercise (“Exercise tests”).

instants when the processed HS signal falls below 50% of its

All tests were performed with informed consent from the

peak, by moving back and forth with respect to the time of the

volunteers and following the principles outlined in the 1964

peak (TS1 (TS2)); 3) the peak-to-peak amplitude of the acquired

Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable

HS signal within DS1 (DS2) interval is associated to AS1 (AS2). ethical standards.

Physical activity processing. In this first prototype, accelera-

Positioning tests. For each subject, we explored 15 differ-

tion data retrieved from the PA sensor are mainly used to provide

ent positions of the HS sensor on the chest (Figure 3). For each

an ON/OFF algorithm to reject from the automatic analysis those

position, the peak-to-peak amplitude of the first heart sound

ECG and HS recordings affected by motion artifacts (“motion-re-

component (AS1) was considered and for each subject, a rep-

jection algorithm”): the acceleration modulus is calculated from

resentative mean value of AS1 (average of 20 heartbeats) was

the X, Y, Z-axis components of the tri-axial MEMS accelerometer

calculated. Representative mean values from the 19 subjects

and it is continuously compared with a predefined threshold

were averaged and a topographic mapping of the thorax for

value that discriminates between motion and rest conditions.

S1 detection was obtained by interpolating the representative

The threshold can be set to fine or coarse increment to interpret

AS1 values within a rectangular region included in an averaged

various g-values of the acceleration modulus: these g-values are thorax size (Figure 3).

Copyright © American Society of Artificial Internal Organs. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 76 MARCELLI

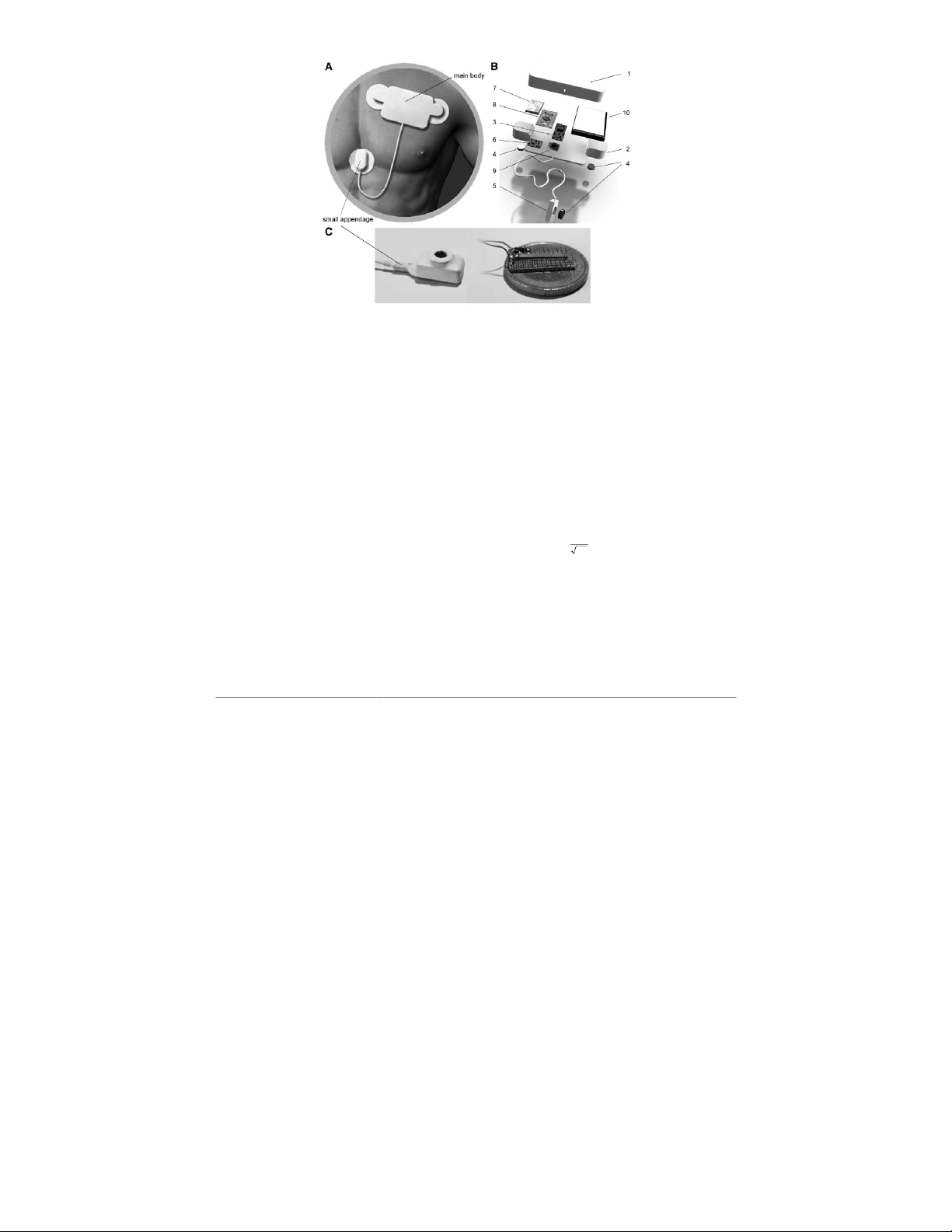

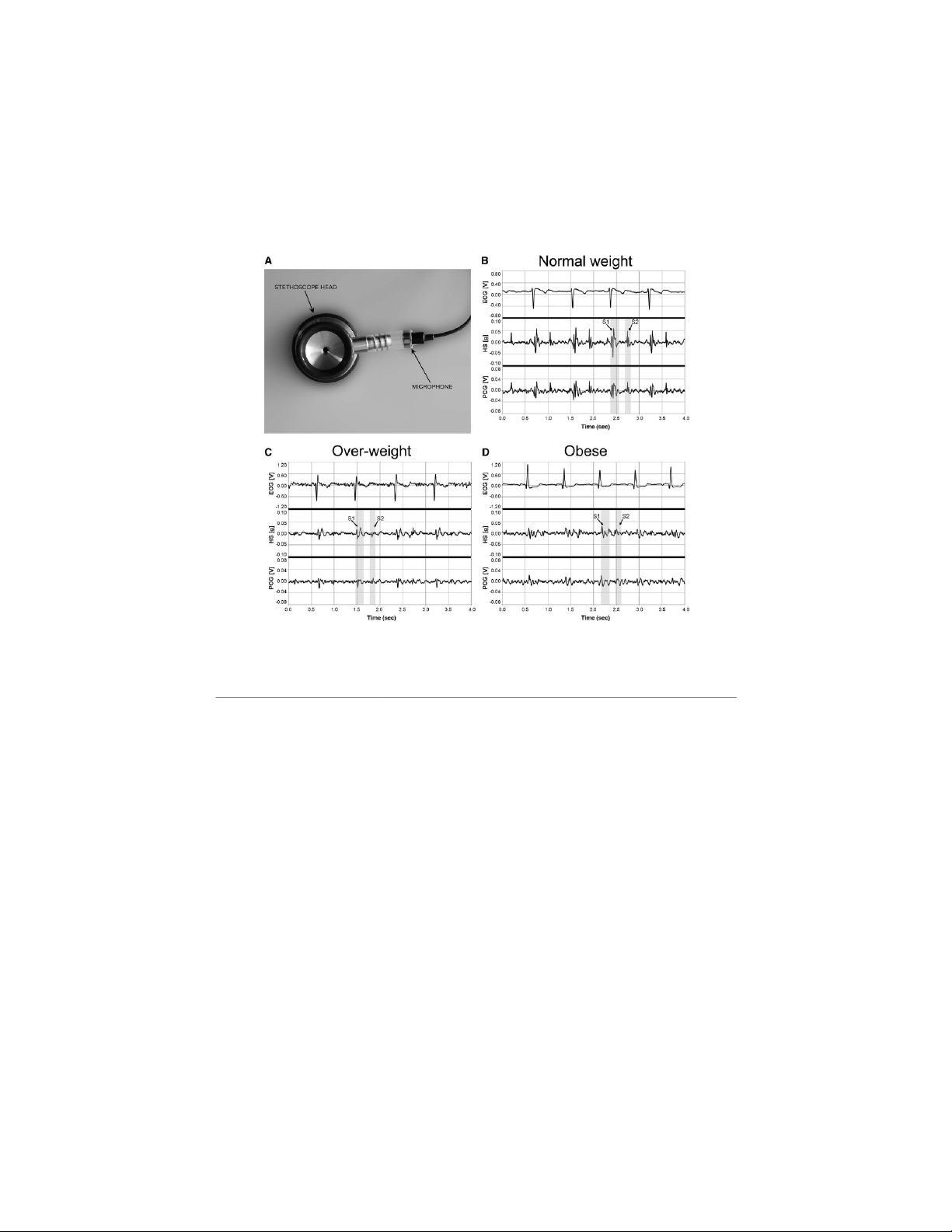

Comparative tests. We considered three subjects repre-

exercise protocol with a peak workload of 2,000 J. The end-

sentative of different body types in the group of volunteers: 1)

point of the exercise test was the achievement of the designed

normal weight (body mass index, BMI = 19.4); 2) over-weight

exercise workload. Immediately after exercise, recordings us-

(BMI = 27.4); 3) obese (BMI = 47.9). The PCG signal was

ing the Multi-Sense CardioPatch were continuously performed

acquired using a self-developed electronic stethoscope com-

with the subject laying in supine position, for 8 minutes of re-

posed of a standard stethoscope head connected to an elec-

covery after exercise. Real-time signal recordings and cardiac

trect condenser microphone (Lavalier RS Pro) with frequency

indexes derived from data processing were displayed on the

response window from 30 Hz to 18 kHz. The microphone

GUI and saved. Electrical (ECG) and mechanical (HS) cardiac

was coupled to the stethoscope head using a piece of PVC

signals corresponding to any possible body motion as detected

tubing, as shown in Figure 4A, and the output of the micro-

by the PA sensor (“motion-rejection algorithm”) were automat-

phone was connected to the PC through an audio input jack.

ically excluded from the analysis.

The HS sensor and the self-developed electronic stethoscope

Statistics. The cardiac indexes, collected for both the maxi-

were positioned in the same most sensitive sternal region on

mum workload condition and the final recovery condition,

the chest, and simultaneous recordings of cardiac vibrations

were expressed as mean ± SD, obtained by averaging 10 car-

from the two systems were provided for each body type, at

diac cycles for each condition. rest conditions.

Relations between the cardiac indexes were assessed using

Exercise tests. Each subject in the group of 19 volunteers

linear regression analysis and Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

was engaged in a step-climbing exercise following a designed

A probability value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Figure 4. Results from tests to compare HS signal provided by the patch with a standard phonocardiogram (PCG) signal: (A) the self-

developed electronic stethoscope, made of a stethoscope head connected to a microphone; ECG, HS, and PCG signals obtained for three

different body types: normal weight (B); over-weight (C); obese (D).

Copyright © American Society of Artificial Internal Organs. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

WEARABLE PATCH FOR ELECTRO-MECHANICAL CARDIAC MONITORING 77 Results

attenuates the higher frequencies and probably introduces a

variable propagation delay. This makes reason of a vibrational

From positioning tests, the most sensitive region for S1

signal less powerful than the myocardial vibrations recorded

detection using the HS sensor was the most inferior part of

endocardially, but it can be still considered a good signal for

the sternum, i.e., the xiphoid process (position 10 in Figure 3).

assessing changes in myocardial contractility.14 Our results for

Comparative tests showed that the HS sensor is effective to

AS1 are consistent with peak values of transthoracic cardiac

acquire heart sound vibrations: in accordance with previous

vibrations previously recorded in healthy subjects by the cuta-

literature on seismocardiography (SCG),14–16 we found a corre-

neous precordial application of an accelerometer sensor.14

spondence between the waves composing the HS sensor signal,

Comparative tests showed that HS signal is reflective as

with distinctive systolic (S1) and diastolic (S2) components, and

much as PCG signal of heart sound vibrations. Indeed, com-

those composing the acoustic signal (PCG signal) detected with

pared with PCG signal, the seismocardiographic signal has

the self-developed electronic stethoscope ( Figure 4). In over-

the advantage of not being contaminated by acoustic noises

weight and obese types, both the PCG and HS signals seem to occurring in the environment.

be attenuated, probably because of the fat layer (Figure 4).

The key advantage of our patch is the capability of assess-

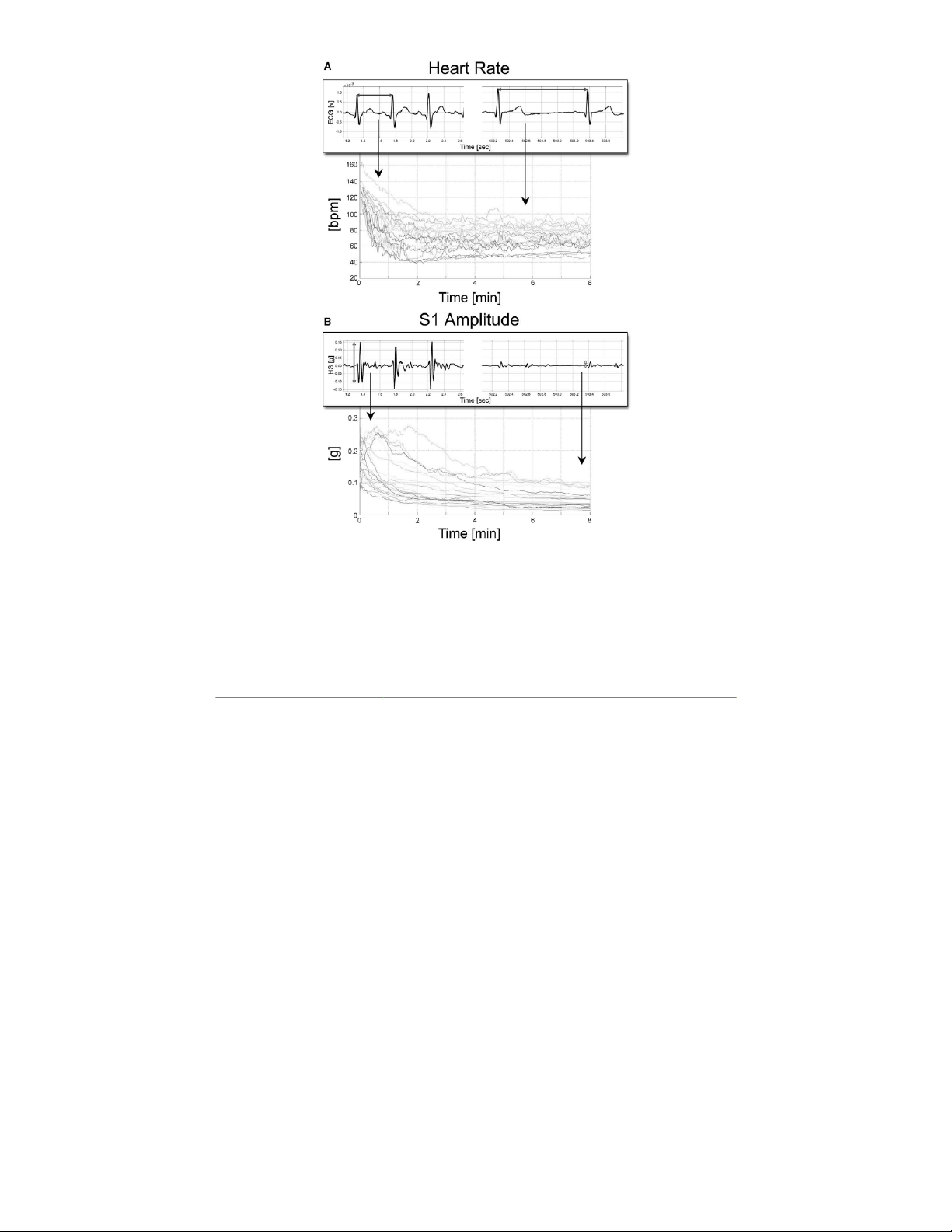

Exercise tests performed for all subjects confirmed the capa-

ing simultaneously both the electrical and mechanical cardiac

bility of the Multi-Sense CardioPatch of measuring stable,

activity, thus providing useful indexes of electro-mechanical

reproducible, and consistent signals for ECG and transthoracic

cardiac performance (e.g., QS1 interval) that can be impaired

cardiac vibrations related to HS. in failing hearts.

For all subjects, the cardiac indexes provided by the patch

In this preliminary study, we performed only measurements

and their relationship were consistent with normal electro-

on healthy subjects, who have a normal response to exercise,

mechanical behavior in nondiseased hearts: in response to

characterized by a positive correlation between contractility

exercise, cardiac contractility (AS1) increases with increases

(mechanical function) and HR (electrical function). In failing

in HR and it recovers from maximal workload condition to

hearts, it is expected that this force–frequency relationship

final recovery (8 minutes after the end of exercise), following

reverses from positive to negative: as a result, increases in HR

a decreasing trend similar to that observed for HR (Figure 5).

reduce contractility, impair exercise tolerance, and precipitate

In the group of subjects as a whole, mean AS1 decreased from

dyspnea and cardiac congestion.22 In heart failure patients,

0.17 ± 0.06 to 0.05 ± 0.03 g, and mean HR decreased from

the assessment of both HR and cardiac contractility (AS1), as

112 ± 23 to 64 ± 11 beats/min, when passing from maximum

provided by our patch, may be extremely useful to detect any

workload condition to final recovery condition. A significant

progressive reversion of this force–frequency relationship, or

positive correlation between AS1 and HR was found (r = 0.79,

any possible improvement of it after a cardiac rehabilitation

p < 0.05) when considering data collected for each patient program.

at maximal workload condition and at final recovery. A mild

In this study, we presented a first generation prototype of the

inverse correlation (r = −0.45, p < 0.05) was found between

Multi-Sense CardioPatch, therefore it still lacks of true wear- DS1 and HR.

ability. Future efforts will be directed to reduce the size and

Mean QS1 obtained for the whole group of volunteers at

the thickness of the patch to provide a most comfortable and

final recovery (48 ± 10 ms) was within the physiologic range for wearable solution.

healthy subjects at rest condition,19 and, in accordance with

Power consumption of the prototype is still high because we

the literature,18 we found that QS1 is inversely related to HR

employed general purpose electronics (e.g., Arduino Pro Mini

(r = −0.72, p < 0.05).

and standard Bluetooth radio module) that require from 60 to

Automatic identification/processing of S2 (AS2, DS2) was not

100 mA. This, with a battery of 1,000 mAh, provides at most

always reliable, because of the low level of S2.

10–15 hours of operation. New generation of microelectronic

systems for wearable medical electronics, such as the recently Discussion

standardized Bluetooth low energy (B E) L technology and the

ultra-low-power ECG System on Chip (ECG SoC)23,24 could be

The Multi-Sense CardioPatch presented in this study expands

employed in a new version of the Multi-Sense CardioPatch to

the physiologic sensing capabilities of wearable systems for

lower power consumption and increase the system lifetime.

heart monitoring, by providing the combination of HS, ECG,

Another critical issue with the current first-generation pro-

and PA recordings. The simultaneous recordings of electri-

totype of Multi-Sense CardioPatch is related to artifacts on

cal (ECG sensor) and mechanical cardiac activity (HS sensor)

the HS signal because of body accelerations (e.g., vibrations

might be beneficial for a more comprehensive evaluation of

due to cough, speech, and motion) retrieved by the HS sen-

cardiac function recovery in patients undergoing cardiac reha-

sor attached on the chest. Motion artifacts represent the major bilitation programs.

obstacle for the evolution of systems based on SCG toward

It has been previously shown that the peak of the myocar-

daily-life monitoring. Some recent studies25–27 have been

dial vibrations occurring in the isovolumic contraction phase

specifically addressed to the challenging aim of removing

(the absolute peak value of first heart sound), detected endo-

motion artifacts from SCG recordings, and they have achieved

cardially using an implantable accelerometer, is an index of

promising results. Pandia et al.25 implemented a polynomial

myocardial contractility and that its directional changes mirror

smoothing filter to cancel motion artifacts in walking sub-

changes in left ventricular peak dP/dt very closely.20,21

jects and their preliminary results showed a primary heart

Our HS sensor is positioned on the chest, therefore it detects

signal detection rate of 99.36% with a false positive rate of

the transthoracic cardiac vibrations that propagate as mechani-

1.3%. Di Rienzo et al.26 developed an algorithm that selects

cal shear waves, and the intervening viscoelastic thoracic tissue

movement-free data segments from 24 hour recordings of SCG

Copyright © American Society of Artificial Internal Organs. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 78 MARCELLI

Figure 5. Signal trends recorded during the Exercise tests: (A) Heart Rate, (B) S1 amplitude (AS1), both recorded with the Multi-Sense Car-

dioPatch: in the foreground boxes, there are examples of ECG and HS signals recorded at maximal workload condition (left side) and after

8 minutes of recovery (right side).

from ambulant subjects. Yang et al.27 recently proposed a novel

by motion artifacts. This obviously limits the HS processing

method of extracting seismocardiographic data from moving

to a “controlled” condition (e.g., patient at rest, no speak-

adult subjects, using a digital signal processing system based

ing). Taking as reference the above-mentioned recent works

on the normalized least mean square adaptive filter, achieving

on motion artifacts cancellation for SCG applications,25–27

a detection rate of SCG recordings of 96% in moving subjects.

signal processing algorithms will be studied to provide dis-

In our early stage prototype, we used the PA sensor to

crimination and automatic removal of artifacts accelerations

exclude from data processing those HS acquisitions affected from HS signals.

Copyright © American Society of Artificial Internal Organs. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

WEARABLE PATCH FOR ELECTRO-MECHANICAL CARDIAC MONITORING 79

Further improvements of the Multi-Sense CardioPatch pro- 1 1. Hansen PB, u

L isada AA, Miletich DJ, Albrecht RF:

totype will include the following: optimization of the process-

Phonocardiography as a monitor of cardiac performance dur-

ing anesthesia. Anesth Analg 68: 385–387, 1989.

ing algorithms to provide a more reliable identification of the

12. Stept ME, Heid CE, Shaver JA, eo L n DF, eo L nard JJ: Effect of alter-

second heart sound component (S2); optimization of the PA

ing P-R interval on the amplitude of the first heart sound in the

sensor processing to expand its use beyond the motion-rejec-

anesthetized dog. Circ Res 25: 255–263, 1969.

tion algorithm by improving the motion pattern recognition

13. Sabbah HN, Stein PD: Investigation of the theory and mechanism

analysis; implementation of patient’s data transmission to a

of the origin of the second heart sound. Circ Res 39: 874–882, 1976.

mobile phone or to an access point to relay the information to

14. Bombardini T, Marcelli E, Picano E, et al: Operator independent

a remote center via Internet.

left ventricular function monitoring during pharmacological

stress echo with the new peak transcutaneous acceleration sig-

nal. Heart 85: 286–289, 2001. Conclusion

15. Zanetti JM, Salerno DM: Seismocardiography: A technique for

recording precordial acceleration. Proceedings of the 4th

We have presented the conceptual design and the first

Annual IEEE Symposium Computer-Based Medical System

prototype implementation of the Multi-Sense CardioPatch, 1991:4–9, 1991.

a wearable patch designed to remotely monitor the electro-

16. Jain PK, Tiwari AK, Chourasia VS: Performance analysis of seis-

mechanical cardiac activity. A preliminary evaluation of the

mocardiography for heart sound signal recording in noisy sce-

Multi-Sense CardioPatch has been performed in 19 healthy

narios. J Med Eng Technol 40: 106–118, 2016.

17. Bazett HC: An analysis of the time-relations of electrocardiograms.

subjects, with promising results. Further optimization of the

Heart 7: 353–370, 1920.

system is required, and then a larger scale evaluation on heart

18. Weissler AM, Harris WS, Schoenfeld CD: Systolic time intervals in

disease patients can be undertaken.

heart failure in man. Circulation 37: 149–159, 1968.

19. De Oliveira NR, Pinheiro MA, Carriço AS, Santos de Oliveira MM, References

Camara MF, Lagreca RJ: Abnormalities of the systolic time inter-

vals obtained by electronic stethoscope in heart failure. Internet

1. Patel S, Park H, Bonato P, Chan , L Rodgers M: A review of wear- J Cardiol 5: 2, 2008.

able sensors and systems with application in rehabilitation.

20. Marcelli E, Vanoli E, Mattera GG, et al: An endocardial accelera-

J Neuroeng Rehabil 9: 1–17, 2012.

tion sensor for monitoring cardiac function of ischemic hearts.

2. Ahsan A, Brahmbhatt A, Cantwell D, Melik-Martirosian A, Meyer

Journal of Mechanics in Medicine and Biology 6: 75–80, 2006.

JA: Wearable sensors for cardiac rehabilitation, in Insights in

21. Delnoy PP, Marcelli E, Oudeluttikhuis H, et al: Validation of a

Engineering Leadership White Paper, No. 2014.4.10, Apr 2014.

peak endocardial acceleration-based algorithm to optimize

3. Pollonini L, Dacso CC: Wearable sensing device for home monitor-

cardiac resynchronization: Early clinical results. Europace 10:

ing of cardiac rehabilitation, in AMAIEEE. Medical Technology 801–808, 2008.

Conference, Boston, USA, October 16th–18th, 2011.

22. Böhm M, La Rosée K, Schmidt U, Schulz C, Schwinger RH,

4. Teng XF, Zhang YT, Poon CC, Bonato P: Wearable medical systems

Erdmann E: Force-frequency relationship and inotropic stim-

for p-Health. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng 1: 62–74, 2008.

ulation in the nonfailing and failing human myocardium:

5. Bonato P: Wearable sensors and systems. From enabling technol-

Implications for the medical treatment of heart failure. Clin

ogy to clinical applications. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag 29: 25–36,

Investig 70: 421–425, 1992. 2010.

23. Altini M, Polito S, Penders J, Kim H: An ECG patch combining

6. Andreu-Perez J, Leff DR, Ip HM, Yang GZ: From wearable sensors

a customized ultra-low-power ECG SoC with Bluetooth low

to smart implants–toward pervasive and personalized health-

energy for long term ambulatory monitoring, in Proceedings of

care. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 62: 2750–2762, 2015.

Wireless Health ’11. San Diego, USA, October 10–13, 2011.

7. Barrett PM, Komatireddy R, Haaser S, et al: Comparison of 24-hour 24. Yang G, Xie ,

L Mantysalo M, Chen J, Tenhunen H, Zheng LR: Bio-

Holter monitoring with 14-day novel adhesive patch electrocar-

patch design and implementation based on a low-power sys-

diographic monitoring. Am J Med 127: 95.e11–95.e17, 2014.

tem-on-chip and paper-based inkjet printing technology. IEEE

8. Chan AM, Selvaraj N, Ferdosi N, Narasimhan R: Wireless patch sen-

Trans Inf Technol Biomed 16: 1043–1050, 2012.

sor for remote monitoring of heart rate, respiration, activity, and

25. Pandia K, Vijayraghavan K, Kovacs GT, Giovangrandi : L Physical

falls. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2013: 6115–6118, 2013.

modeling of low-frequency sound propagation through human

9. Chakravarthy N, Engel JM, Chavan A, Finlay B, Nosbush G: A

thoracic tissue. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2010: 2455–

study of activity and body posture with the PiiX mobile body- 2458, 2010.

adherent device. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2014: 2714–

26. Di Rienzo M, Meriggi P, Rizzo F, et al: A wearable system for the 2717, 2014.

seismocardiogram assessment in daily life conditions. Conf

10. Durand LG, Langlois YE, Lanthier T, et al: Spectral analysis and

Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2011: 4263–4266, 2011.

acoustic transmission of mitral and aortic valve closure sounds

27. Yang C, Tavassolian N: Motion artifact cancellation of seismocar-

in dogs. Part 4: Effect of modulating cardiac inotropy. Med Biol

diographic recording from moving subjects. IEEE SENSORS J

Eng Comput 28: 439–445, 1990. 16: 5702–5708, 2016.

Copyright © American Society of Artificial Internal Organs. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.