Preview text:

lOMoARcPSD|45316467 lOMoARcPSD|45316467

International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Business Review

j o u r n a l h o m ep a g e: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c at e / i b u s r e v

Foreign institutional investors and dividend policy: Evidence from China

Lihong Caoa, Yan Dub,*, Jens Ørding Hansenc

aBusiness School, Hunan University, China b

EDHEC Business School, France

c University of Agder, Norway and Niels Brock Copenhagen Business College, Denmark ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Received 19 February 2016

This study examines whether foreign institutional investment influences firms’ dividend policies. Using data from all

Received in revised form 11 January 2017

domestically listed nonfinancial firms in China during the period of 2003–2013, we find that foreign shareholding

Accepted 2 February 2017 Available online

influences dividend decisions and vice versa. 13 February 2017

Furthermore, changes in dividend payments over time positively affect subsequent changes in foreign

shareholding, but the opposite is not true. Our study indicates that foreign institutional investors do not change Keywords:

firms’ future dividend payments once they have made their investment choices in China. Moreover, they self-select Foreign institutional investor

into Chinese firms that pay high dividends. Our evidence suggests that in an institutional setting where foreign Dividend

investors have tightly restricted access to local securities markets and a relatively high risk of expropriation by Agency theory

controlling shareholders exists, firms can use dividends to signal good investment opportunities to foreign Signaling theory Corporate governance investors.

© 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

0969-5931/© 2017 Elsevier Ltd. Al rights reserved. 1. Introduction

One important manifestation of the increasing integration of the

global economy in the past several decades has been the gradual

opening of developing countries’ securities markets to international

investors. In response to this trend, foreign institu-tional investment

has proliferated in emerging markets. While the growth potential of

corporations in these markets offers a tantalizing prospect of high

returns, foreign investors face information disadvantages because of

geographic distance, lan-guage barriers, and cultural differences.

Further, many emerging markets are characterized by weak protection

of minority shareholder rights, and foreign investors’ exposure to the

risk of expropriation by controlling shareholders gives them a strong

incentive to be vigilant in protecting their investments. This raises the

question of whether foreign investors play an active role in the

corporate governance of local firms.

This study addresses this question by examining the relation-ship

between foreign investors and the dividend policies of Chinese listed

firms. In November 2002, China partially opened its

* Corresponding author at: EDHEC Business School, 24, Avenue Gustave Delory—

CS 50411, 59057 Roubaix Cedex 1, France.

E-mail addresses: c aolhjy@gmail.com (L. Cao), y an.du@edhec.edu (Y. Du), je

nsordinghansen@gmail.com (J.Ø. Hansen).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.02.001

shares were held by QFIIs in 2012 (Jiang & Kim, 2015). Therefore,

one may expect that foreign institutional investors in China are

dispersed outsiders who do not have the incentive or power to exert

domestic stock market to foreign institutional investors by launching a

oversight over the firms in which they invest. However, some studies

scheme assigning investment quotas to qualified foreign institutional

find evidence that foreign investors stabilize the Chinese capital

investors (QFIIs) that were officially approved by the China Securities

market (Han, Zheng, Li, & Yin, 2015) and play an effective monitoring

Regulatory Commission (CSRC). Since then, the system has been

role in the corporate governance of state-controlled Chinese firms

gradually expanded, and by the end of 2015, 294 international

(Huang & Zhu, 2015). While the literature on the impact of foreign

financial institutions had QFII status in China. Because of the quota

shareholding in other emerging markets that are more open to foreign

scheme, foreign institutional investors do not play as large a role in the

investors is growing (Baba, 2009; Buckley, Munjal, Enderwick, &

Chinese stock market as in other emerging markets that have a more Forsans, 2015; D

esender, Aguilera, Lópezpuertas- L amy, & Crespi,

liberal approach to foreign investment. For example, only 1.4% of A

2014; Jeon, Cheolwoo, & Moffett, 2011; Kim, Sul, & Kang, 2010), the

role of foreign institutional investors in China is not well known. lOMoARcPSD|45316467

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827 817

The corporate governance literature shows that the principal–

centers on governance aspects such as firm restructuring (Ahmadjian

principal agency problem is pronounced in developing countries such

& Robbins, 2005), dismissing poorly performing CEOs (Aggarwal, Erel,

as China (Claessens & Fan, 2002; Jiang & Kim, 2015; La Porta,

Ferreira, & Matos, 2011), board monitoring (Desender et al., 2014),

Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, 2000; Song, Wang, & Cavusgil,

firm performance (Douma, George, & Kabir, 2006; Aggarwal et al.,

2015). The Chinese institutional environment is characterized by weak

2011), and ownership (Leuz, Lins, & Warnock, 2009). The relationship

investor protection, concentrated ownership structures, and high levels

between foreign institutional investment and corporate dividend policy

of government and political influence (Claessens, Djankov, & Lang,

has received less attention. This oversight is remarkable because

2000; Chen, Chen, Schipper, Xu, & Xue, 2012; Fan

dividends, unlike accruals, cannot be easily falsified or manipulated. & W

ong, 2002 ). As a result, the controlling shareholder (usually a

Therefore, they are an attractive variable to study, particularly in

state-owned entity) of a Chinese listed firm is likely to have both the

emerging markets, which are often characterized by unreliable

power and the incentive to divert corporate resources from minority

accounting and auditing practices.1

shareholders and extract private benefits of control. Unlike their local

counterparts, foreign institutional investors do not face political

Second, in the small but growing literature on the impact of foreign

pressure to facilitate state shareholders’ expropriation of wealth from

institutional investment on corporate dividend policy in emerging

minority shareholders (Firth, Lin,

markets, existing studies imply that foreign investors enhance & Z

ou, 2010 ; Huang & Zhu, 2015) and are unlikely to have potential

monitoring and improve corporate governance quality in countries that

business ties with the listed firms they have invested in (Firth et al.,

have poorly developed legal institutions (Baba, 2009; Desender et al.,

2016). Thus, foreign institutional investors are independent and can

2014; Jeon et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2010). While these insights are

therefore theoretically be more effective at monitoring controlling

valuable, they are mainly based on studies focused on Japan and

shareholders. Research shows that dividends play an important role in

Korea. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine

disciplining managers and mitigating agency conflicts between insiders

the impact of foreign institutional investors on dividend policy in China,

(e.g., managers and controlling share-holders) and outside minority

where foreign investors’ access to local securities markets is more

shareholders. Dividend payouts to shareholders reduce the amount of

tightly restricted and a relatively high risk of expropriation by controlling

cash under insiders’ control and consequently limit the opportunities

shareholders exists. Recently, H

uang and Zhu (2015) find that foreign

for insiders to spend cash inefficiently or divert it to themselves at the

institutional investors may play a beneficial role in limiting expropriation

expense of outside shareholders (Easterbrook, 1984; Jensen, 1986).

by controlling shareholders in China. Consistent with Huang and Zhu

Thus, we argue that foreign institutional investors can induce

(2015), our findings support a positive influence of foreign managers to pay out dividends.

shareholding on dividend payments. More importantly, our findings

suggest that foreign investors tend to prefer investing in Chinese listed

In addition to the proactive role of monitoring managers, dividends

firms that already have more generous payout policies. In this way, our

can function as a substitute for poor legal protection of shareholders

study complements the existing literature on the impact of foreign

(La Porta et al., 2000). This is particularly relevant in the Chinese

institutional invest-ment in emerging markets and presents an

setting. Foreign institutional investors investing in Chinese listed firms

alternative interpreta-tion to the one offered by Huang and Zhu (2015).

experience significant information asymmetry because of the

geographical, institutional, and cultural distance they face. However,

they are typically large and sophisticated institutions with resources

Finally, while prior studies examining the relationship between

and skills that allow them to collect value-relevant information and

dividend policy and institutional ownership focus mainly on the U. S.

invest their holdings prudently (Gul, Kim, & Qiu, 2010). Having limited

and other developed markets (Grinstein & Michaely, 2005; Short,

knowledge of local conditions, such investors may be particularly

Zhang, & Keasey, 2002),2 the potential impact of institutional

sensitive to signals of firm governance quality. They will prefer to

ownership in China has been comparatively neglected. Given the

invest in well-managed firms that have a reputation for equitable

continuous growth of China’s economy and ongoing development of its

treatment of shareholders. Following this line of thought, we argue that

capital market, the role played by institutional investors in China can

Chinese listed firms can use dividend payouts to establish a reputation

no longer be ignored. Recently, F

irth et al. (2016) find that mutual

for moderation in expropriating the wealth of outside investors and

funds, an important type of institutional investor, influence firms to pay

thereby attract foreign institutional investment.

higher dividends in China. Although the findings are interesting, they

do not differentiate the effects of foreign and domestic investors. This

Using data from 1592 publicly listed Chinese firms during the

study complements Firth et al. ( 2016) by showing that foreign

period of 2003–2013 (14,706 firm-year observations), we find a

institutional investors investing in Chinese listed firms under the quota

significant positive association between foreign shareholding and

scheme have different incentives to monitor firms and influence their

dividends. Moreover, our simultaneous equation models using the

dividend payouts, as compared to their domestic counterparts.

generalized method of moments (GMM) method show that foreign

Moreover, foreign institutional investors are more attracted to dividend

shareholding influences corporate dividend payouts, and vice versa.

increases than their domestic counterparts.

Thus, in an institutional environment with weak investor protection,

foreign shareholding and dividends are jointly deter-mined and

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2 we

influence each other in a positive manner. Furthermore, we study the

review prior literature on dividend policy and develop our

relationship between changes in dividends and changes in foreign

shareholding. We find that firms that increase their dividend payments

wil subsequently have a larger propor-tion of foreign institutional

shareholdings. By contrast, there is no significant effect of a change in

1 In China, for example, there have been several examples of publicly listed firms

the shareholding of foreign institutional investors on subsequent

having used inaccurate bank statements (with or without col usion of the bank in

question) to deceive auditors. In fact, contrary to intuition, faking cash balances seems

dividend payments. This suggests that foreign investors self-select into

to be one of the easier ways to distort corporate accounts. For an egregious example, firms paying higher dividends.

see Deloitte’s resignation letter to Longtop Financial Technologies from May 2011,

which is registered with the SEC:

http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/ d

ata/1412494/000095012311052882/d82501exv99w2.htm (retrieved on January

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, while 31, 2016).

a substantial body of literature exists on the impact of international

2 We thank an anonymous referee for drawing our attention to the relevance of these articles

ownership on corporate governance, prior research to our study. lOMoARcPSD|45316467 818

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827 hypotheses. In Section 3

we introduce the research design and

minority shareholders (Du & Dai, 2005; Faccio et al., 2001; Song et al.,

methodology. Results are presented in Section 4, and Section 5

2015). Outside investors are at a disadvantage in benefiting from their concludes.

investment because insiders prefer to keep cash in the firm or divert it

to themselves. Dividends, which are shared by all investors on a pro

2. Foreign institutional investors and corporate governance in China

rata basis, thus mitigate the agency costs associated with the

deployment of free cash flow (Easterbrook, 1984; Faccio et al., 2001; Jensen, 1986).

Despite increasing direct investment in China by foreign

Given that managers naturally prefer to retain surplus cash instead

companies, foreign portfolio investors were legally prohibited from

of paying out dividends, the question arises as to who can induce them

investing in the Chinese domestic stock markets until November 2002,

to pay dividends. Grinstein and Michaely ( 2005) argue that institutional

when the QFII scheme opened the A share market to foreign

investors typically have large amounts at stake and are wel informed,

institutional investors that were officially approved by the CSRC. Since

and hence have incentives to devote resources to monitoring and to

then, the rapidly growing Chinese economy has attracted a wide press for dividend payments. F

irth et al. (2016) argue that institutional

variety of institutional investors—investment banks, pension funds,

investors can communicate with management teams directly and

insurance firms, sovereign wealth funds, and others—from around the

exercise voting rights during shareholder meetings. Alternatively, they

world. Foreign institutions that attain QFII status are granted a quota

can influence a firm’s dividend payout by the implicit threat of selling

that they can use to buy A shares (i.e. domestically traded shares

their shares. Empirical evidence with respect to the relationship

denominated in domestic currency) as wel as other domestic financial

between institutional investors and dividends is mixed. For example,

products.3 Foreign institutional investors approved so far are

Grinstein and Michaely (2005), using a sample of public U.S. firms, do

exclusively large, reputable international investors such as UBS,

not find empirical support that institutions cause firms to increase

Morgan Stanley, Nomura Holdings, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, HSBC,

payouts. Short et al. (2002), using a sample of U.K. public firms, find a

Deutsche Bank, and so forth. The system has been gradually

positive association between institutional investment and dividend

expanded, and by the end of 2015, 294 international financial payments. F

irth et al. (2016) examine this relationship in the China institutions had QFII status.

setting and find that only one class of institutional investors – mutual

In China, the privatization of state-owned companies has resulted

funds – influence firms to pay higher cash dividends. While these

in a prevalence of concentrated ownership in listed firms (Chen, Jian,

studies provide important insights, less is known about the role of

& Xu, 2009; Sun & Tong, 2003; Wang & Wong, 2003). For example,

foreign institutional investors in the corporate governance of listed

Chen et al. (2009), in an examination of 1271 firms listed on the firms in China.

Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 1990 to 2004, find that

the controlling shareholder holds around 44% of the shares on

average. The concentrated ownership structure allows a controlling

As the institutional framework in China is characterized by weak

shareholder (usually a state-owned entity) to dominate the board of

investor protection, concentrated ownership structures, and relatively

directors and the top management team (Chen, Firth, Gao, & Rui,

inexperienced individual investors, insiders often expropriate wealth

2006). In addition, legal institutions for the enforce-ment of ownership

from minority shareholders (including foreign shareholders). Moreover,

rights remain relatively underdeveloped, though the degree of

most Chinese listed firms are ultimately controlled by state-owned

underdevelopment varies by region (Li & Qian, 2013). The

entities that do not consider dividends to be the main source of return

combination of a concentrated ownership structure and weak

received from listed firms.5 Therefore, Chinese listed firms generally

governance mechanisms enables controlling shareholders to

do not have much incentive to keep dividends high in order to transfer

expropriate company wealth at the expense of minority shareholders

wealth to all shareholders. We argue that foreign institutional investors

(Berkman, Cole, & Fu, 2009; Cheung, Jing, Lu, Rau, & Stouraitis,

are more independent of management and controlling shareholders

2009; Clark, 2003; Du & Dai, 2005; Faccio et al., 2001).

than their local counterparts, who often face political pressure to

facilitate state shareholders’ expropriation of company wealth (Firth,

Lin, & Zou, 2010) or have potential business ties with the listed firms

3. Foreign institutional investors and dividends

they have invested in (Firth et al., 2016). Therefore, they have a

heightened incentive to monitor controlling shareholders and push for

The finance literature attempts to explain the puzzle of corporate

equitable treatment of all shareholders. Consistent with this argument,

dividend policy primarily by using two lines of reasoning: agency and

previous studies present evidence that the presence of foreign

signaling theories (see Baker, 2009, for an overview of different

institutional investors can be an effective way to enhance monitoring

schools of thought on dividend policy).4 In this section we develop

(Gul et al., 2010; He, Li, Shen, & Zhang, 2013). For instance,

hypotheses from both perspectives. A

ggarwal et al. (2011) find that international institutional investment

leads to subsequent improvement in governance in a broad range of

3.1. An agency perspective

countries. More specifically, B

aba (2009) finds that foreign institutional

ownership is associated with higher dividends in Japan, and Kim et al.

Agency theory acknowledges the existence of conflicts between ( 2010) and Je

on et al. (2011) report similar findings for South Korea.

outside investors and insiders (managers, controlling share-holders) of H

uang and Zhu (2015) and Han et al. (2015) find that QFIIs help raise

a firm. Research shows that firms in developing countries are

the standards of corporate governance

especially subject to the principal–principal agency problem that arises

from the conflicts between controlling and

3 See Walter and Howie (2006), Ch. 11, for details on the QFII scheme.

4 Another explanation of dividend policy is tax incentives (see e.g., Dahlquist &

5 Taxes paid by listed firms are significantly higher than dividends. For example,

Robertsson, 2001). Since QFIIs are currently exempt from business taxes on capital

from 2006 until 2010, firms control ed by the State-owned Assets Supervision and

gains and some of them are entitled to preferential tax treaty benefits for withholding

Administration Commission (SASAC) paid 168.6 bil ion yuan in total dividends but 5

taxes of dividend, tax-based explanations of dividend behavior are less relevant in our

tril ion in taxes (South China Morning Post, February 23, 2011: “State firms to hand context.

over more profits to Beijing”). lOMoARcPSD|45316467

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827 819

and stabilize the capital market in China. Thus, based on the existing

money will not be expropriated (Grinstein & Michaely, 2005; Jiraporn &

literature, there is reason to predict that foreign institutional investors in

Ning, 2006; Kim & Yi, 2015). In light of the above discussions, we

China make an active effort to reduce information asymmetry, promote

propose the following hypothesis:

dividend payments, and reduce management’s ability to squander

firms’ resources. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. All else equal, firms that pay higher dividends attract

greater foreign institutional holdings.

Hypothesis 1. All else equal, greater foreign institutional holdings lead to 4. Methodology

firms paying higher dividends. 4.1. Data and sample

3.2. A signaling perspective

The data set consists of all nonfinancial firms listed on the

Our second hypothesis concerns the impact of dividends on foreign

Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges during the time period of

institutional ownership. Signaling theories are based on the

2003–2013. We retrieve accounting and shareholder information from

assumption that firm insiders (e.g., managers or controlling

the Chinese CSMAR database using the following criteria. First, we

shareholders) know more than outsiders (e.g., minority share-holders)

select all firms listed on the Shenzhen and Shanghai stock exchanges

about a firm’s growth opportunities, governance quality, and so forth.

for which complete information is available for 2003–2013. This leads

In the context of information asymmetries between insiders and

to a total of 1645 firms with 15549 firm-year observations. Second, we

outsiders, firms can demonstrate their commitment to good corporate

exclude financial firms (275 firm-year observations) because they may

governance standards by consistently and voluntarily paying high

have different incentives for paying dividends. Third, we exclude firms

dividends (Miller & Rock, 1985). Grinstein a nd Michaely (2005) argue

that are listed in CSMAR as being ultimately foreign-controlled (568

that institutional investors prefer dividends to retained earnings as

firm-year observa-tions), reasoning that they are effectively foreign

firms paying stable dividends are considered prudent investments.

subsidiaries and cannot be compared to ordinary listed firms with

Thus, firms paying stable dividends are able to attract institutional

respect to the impact of foreign ownership. Applying these criteria

investors and raise external finance. Moreover, many firms maintain a

results in a final sample of 1592 publicly listed Chinese firms for a total

regular pattern of dividend payments because investors prefer such

of 14706 firm-year observations.

regularity for psychological reasons (Graham & Kumar, 2006; Shefrin,

2009). In particular, firms operating in an environment of relatively

weak legal protection of shareholders can use dividends as a

4.2. Variable measurement

substitute for such protection (La Porta et al., 2000). The empirical

research based on data from the U.S. and other developed markets 4.2.1. Dividends

does not support the signaling role of dividends in attracting

In this study we focus on cash dividends and measure corporate

institutional investors. For example, G

rinstein and Michaely (2005) find

dividend policy based on two variables in our main analysis: dividend

no evidence that U.S. public firms that face more asymmetric

and dividend payer. Dividend is the ratio of dividends to total assets,

information (small firms and high market-to-book firms) are able to use

similar to the measurement used in Ben-Nasr (2015) and Grinstein

dividends to attract institutional investors. On the contrary, they find

and Michaely (2005). Following the definition used by Firth et al.

that institu-tional investors as a group reduce their holdings in firms ( 2016) and B

aba (2009) among others, Dividend payer is a dummy

that increase their dividend payout. One emerging-market study by

equal to one if the firm pays dividends, and zero otherwise. In the

Fairchild, Guney, and Thanatawee (2014), using a sample of widely

robustness check, we add two additional measures: dividend yield and

held Thai firms, find little support for the signaling hypothesis.

dividend payout. Similar to Dahlquist and Robertsson (2001), we define

Dividend yield as common dividends divided by the market value of

equity. Similar to Adjaoud and Ben-Amar (2010), Dividend payout refers

to the payout ratio, that is, dividends divided by net earnings. In

Research has shown that the signaling perspective is more

addition to cash dividends, open-market share repurchases have

relevant in emerging markets like China where formal legal protection

become an increasingly popular method during the last decade for

of minority shareholders is imperfectly developed (La Porta et al.,

firms in many countries to return excess cash to shareholders. We 2000). For example, S

u et al. (2014) suggest that Chinese firms with follow

political connections pay higher dividends, signaling to investors the

expected future profitability resulting from privileged access to key

resources. Compared with their local counterparts, foreign institutional

investors face geographical, institutional, and cultural distance, which

6 The approach taken to share repurchases by the Company Law of China in both

its original version from 1993 and its updated 2005 edition is that the law prohibits firms

magnifies the informa-tion asymmetry vis-à-vis management and

from buying their own shares back by default in accordance with a principle of capital

controlling share-holders (Buckley, 1997; Desender et al., 2014; Leuz

preservation (Gu, 2010; pp 279–280). However, the Company Law does permit firms to

et al., 2009). Moreover, because they hold a relatively small stake,

repurchase shares in special circumstances (i.e., see Article 149 of the 1993 Company

foreign institutional investors’ ability to effectively monitor management

Law; Article 143 of the 2005 Law). In practice the attractiveness of buybacks is sharply

limited by several factors. First, firms are not al owed to hold treasury shares with a

may be limited (Douma et al., 2006). Furthermore, foreign institutional

view to sel ing the shares back to the market later. Since issuing shares is associated

investors in China are typically large and sophisticat-ed institutions

with considerable regulatory and bureaucratic hurdles in China, very few firms that

with resources and skil s that allow them to collect value-relevant

have managed to issue shares in the first place are interested in undoing the process

information and invest their holdings prudently (Gul et al., 2010). Thus

through a repurchase (Zhou & Zeng, 2003). Second, since share repurchases entail a

reduction of the company’s registered capital, such transactions are subject to strict

they will be purposefully seeking assurances that they will not be

creditor protection provisions under the Company Law, which makes them more

harmed by their disempowered status as minority shareholders.

complicated to implement than dividends (The creditor provisions are in Article 178 of

Having limited knowledge of local con-ditions, such investors may be

the 2005 Law). As a result of these impediments, share repurchases were hardly ever

particularly sensitive to signals of firm governance quality. A historical

used by Chinese listed firms as an alternative to dividends during the period studied

here, although they were occasional y used for the purpose of changing a company’s

pattern of generous and stable dividend payments may help to share class structure. See G

u (2010, p. 260) on the buyback of B shares and Walter

convince the investors that their

and Howie ( 2006, p. 180) on the buyback of nontradable state shares. lOMoARcPSD|45316467 820

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827

previous empirical studies on the dividend policy of Chinese listed

generated from their operating activities to finance their positive net

firms (Chen et al., 2009; Su, Fung, Huang, & Shen, 2014; Zhang,

present value projects. Therefore, they are less likely to pay dividends.

2008) in not making any adjustments for the impact of share

We include two variables to measure a firm’s growth opportunities.

repurchases on dividend policy because share repurchases were a

Market to book is the ratio of the market value of equity to the book

highly uncommon means of disbursing cash to shareholders during the

value of equity, as is used in B

aba (2009) and Jeon et al. (2011), time period we are studying.6

among others. This variable has been found to be negatively

associated with dividend policy in the literature (e.g., Adjaoud & Ben-

4.2.2. Foreign shareholding

Amar, 2010; Chen et al., 2009). The second variable representing

We identify foreign shareholding by matching the official list of

growth opportunities is Intangible, which is calculat-ed as intangible

QFIIs with the firm’s ten largest shareholders collected from CSMAR

assets divided by total assets.

database. Restricting attention to QFIIs, as opposed to other foreign

Second, larger and more profitable firms are expected to pay

investors, has the advantage of avoiding including industrial investors

higher dividends (Adjaoud & Ben-Amar, 2010; Holder, Langrehr, &

in the dataset. This is important because such investors may be driven

Hexter, 1998). Therefore, we include Firm size, which is measured by

by strategic interests that are irrelevant to institutional investors (and to

the natural logarithm of total assets, following Adjaoud and Ben-Amar

this study). We used the official list of QFIIs which was published on

( 2010) and Baba (2009), among others. We also control for Cash

the website of the CSRC in July, 2014. The list includes the English

holding, which is calculated by cash and cash equivalents divided by

and Chinese names of all institutions currently approved as QFIIs

total assets, similar to the measurement used in Jeon e t al. (2011) and

along with the date of approval. In addition to strictly foreign

Shao, Kwok, and Guedhami (2013). A firm’s cash holding is likely to

institutions, the list also comprises institutions from Hong Kong,

influence its ability to pay dividends. The same is true of ROE, which is

Macau, and Taiwan. However, the list does not include institutions that

the after-tax return on equity, following Adjaoud and Ben-Amar (2010)

held QFII status in the past but subsequently lost it for some reason and Fairchild et al. (2014).

(e.g., Lehman Brothers, which went bankrupt in 2008). In order not to

Third, highly leveraged firms may pay lower dividends. Creditors

overlook institutions that obtained QFII status in the early years of the

may limit dividend payouts in order to protect their own interests in a

QFII scheme but are no longer on the official list, we checked the

firm. Moreover, large creditors are able to monitor the behavior of

official QFII list published in April, 2006, available in Walter and Howie

management, which alleviates potential free cash flow problems and

(2006). Our final list of foreign institutional investors, then, consists of

the necessity of paying dividends. Therefore, we control for Leverage,

QFIIs that are either on the official list (2014 version), or the official list

which is total liabilities divided by total assets, similar to the

(2006 version) or both. Moreover, we have assigned QFII status not

measurement used in Shao et al. (2013).

only to entities that match the official name (in either English or

Chinese) of a QFII exactly but also to affiliated entities, in recognition

Fourth, prior research has shown that managerial ownership helps

of the fact that the names of particular institutional shareholders are

to resolve the agency conflicts between outside shareholders and

not always recorded in the same way and with the same level of detail

managers. Consistent with this argument, Agrawal and Jayaraman in CSMAR.

( 1994) find that managerial ownership and dividends are substitute

mechanisms for controlling the agency costs of free cash flow. When

In this study, Foreign shareholder is a dummy variable equal to one

managerial ownership is high, there is a high goal alignment between

if at least one of the ten largest shareholders is foreign, and zero

managers and shareholders, making dividends less necessary.

otherwise. Foreign share is the proportion of shares held by foreign

However, several scholars argue that managers will become

shareholders identified as described above; if a firm has more than

entrenched above certain ownership levels (Farinha, 2003), and

one foreign shareholder among its ten largest, the percentages for

increase dividend payments if they feel restricted in selling their shares

these shareholders are added up. In the robustness check, we

in the company (Firth et al., 2016). Therefore, similar to Firth et al.

introduce a dummy variable (High foreign) equal to one if the foreign

( 2016) and others, we control for Managerial ownership (Managerial),

ownership of a given firm is higher than our sample median foreign

which is the proportion of shares hold by top managers of the firm. ownership and zero otherwise.

Fifth, prior literature suggests that state ownership positively

4.2.3. Control variables

influences a firm’s dividend policy. For example, Adjaoud and Ben-

We include firm-specific control variables that have potential A

mar (2010) argue that in firms with partial state ownership, paying

influence on dividend policy. First, we control for a firm’s growth

dividends will indicate to the shareholders that the privatized firm is

opportunities. When firms grow rapidly, they need funds performing well. F irth et al. (2016) argue that Table 1

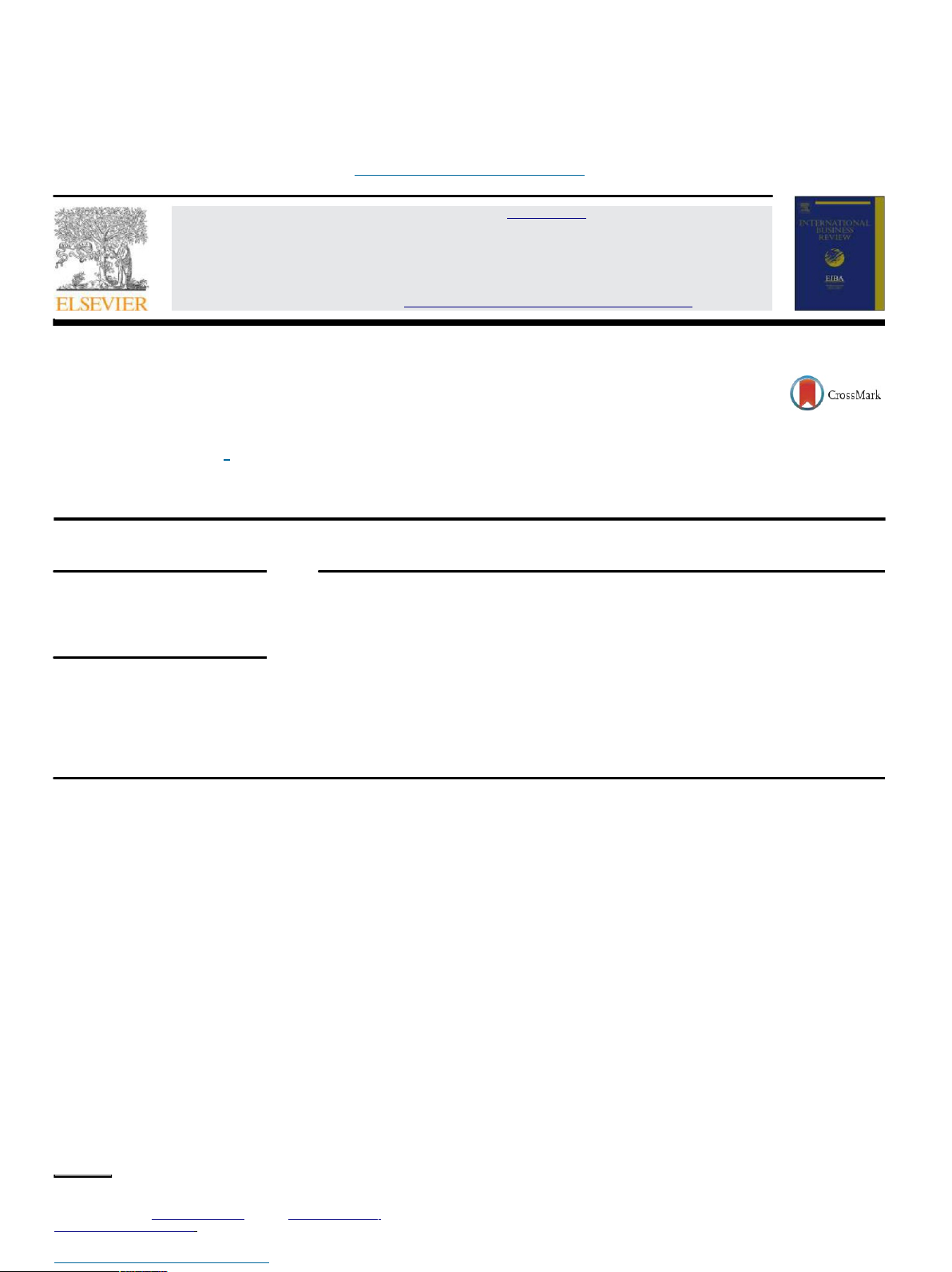

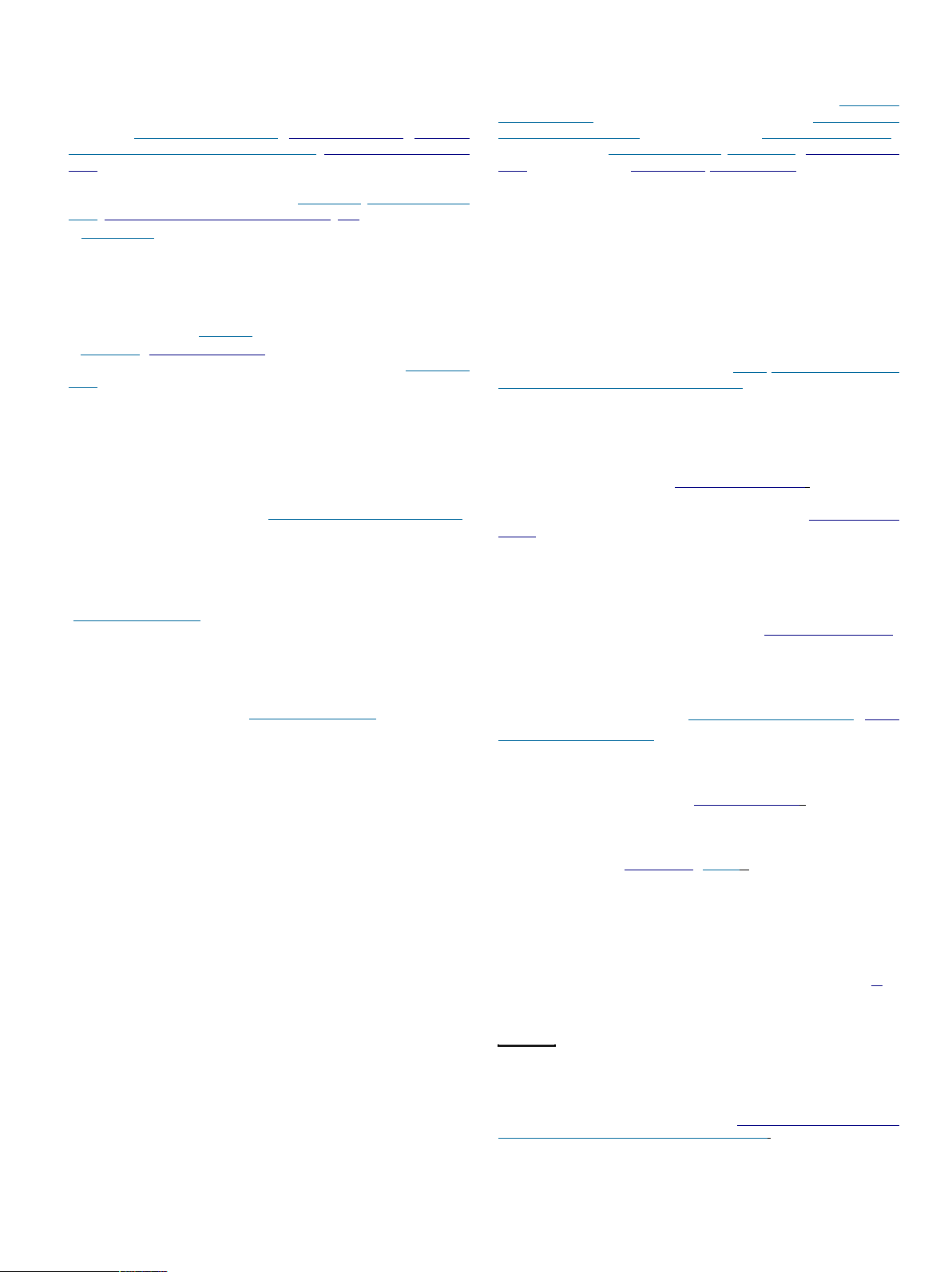

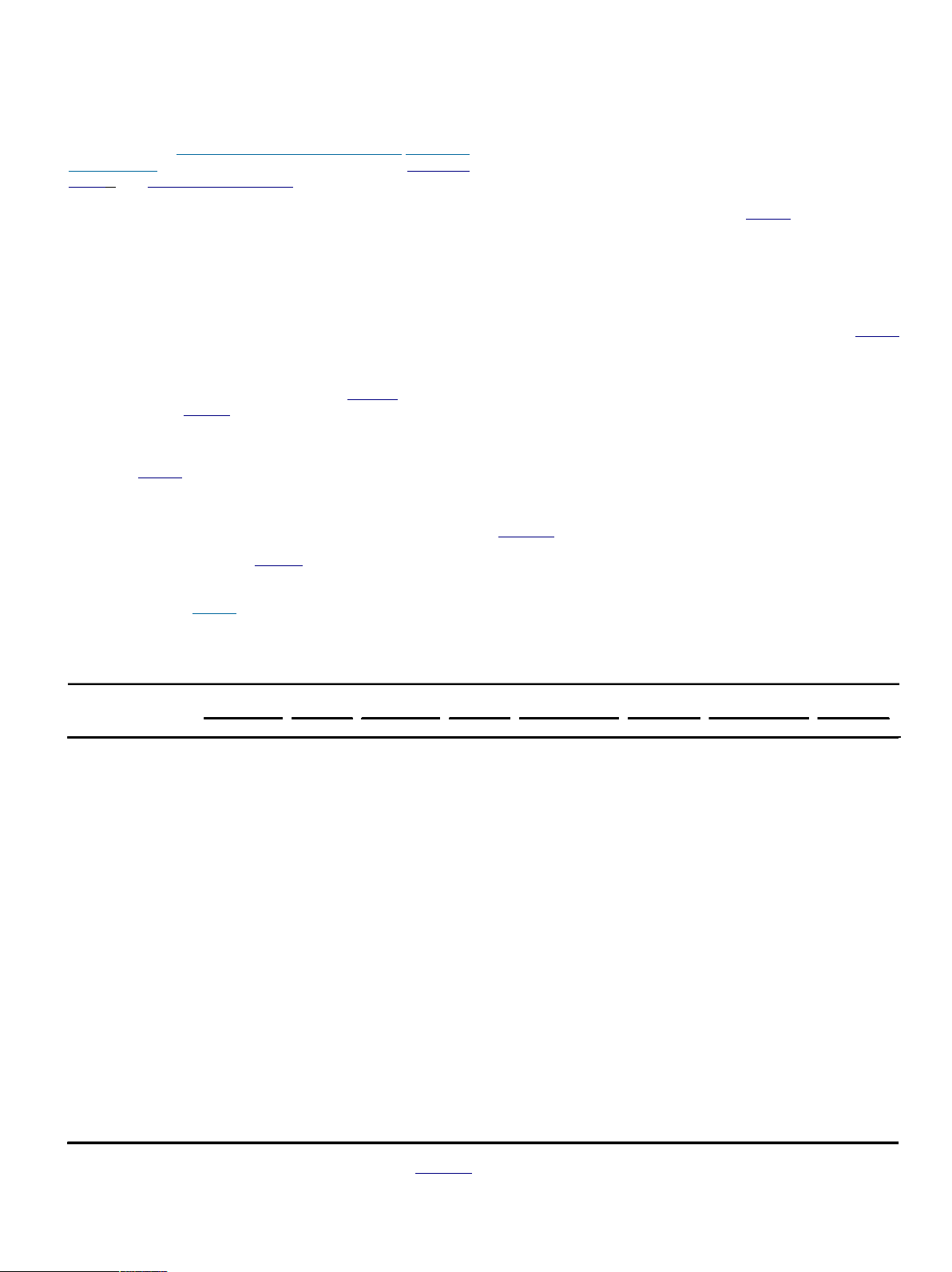

Descriptive statistics, multicollinearity indices, and Pearson correlations. Mean SD VIF 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1. Dividend 0.001 0.016 1.00 2. Dividend payer 0.552 0.497 0.59 1.00 3. Foreign shareholder 0.127 0.334 1.62 0.14 0.14 1.00 4. Foreign share 0.002 0.008 1.57 0.13 0.09 0.60 1.00 5. Market to book 3.396 4.034 1.08 0.01 0.13 0.02 0.01 1.00 6. Firm size 21.627 1.275 1.20 0.09 0.33 0.21 0.13 0.24 1.00 7. Cash holding 0.159 0.118 1.17 0.27 0.20 0.01 0.01 0.06 0.09 1.00 8. ROE 0.057 0.225 1.04 0.21 0.24 0.06 0.06 0.11 0.10 0.12 1.00 9. Leverage 0.528 0.255 1.13 0.35 0.25 0.05 0.02 0.04 0.08 0.31 0.03 1.00 10. Intangible 0.045 0.058 1.04 0.04 0.10 0.00 0.03 0.08 0.09 0.14 0.05 0.02 1.00 11. Managerial share 0.029 0.100 1.19 0.12 0.11 0.03 0.03 0.06 0.13 0.15 0.05 0.13 0.02 1.00 12. State-owned 0.647 0.478 1.23 0.01 0.06 0.08 0.04 0.11 0.25 0.07 0.03 0.01 0.04 0.37 1.00

N = 14706. Bold type denotes significance at the 0.1% level. See A

ppendix A for variable definitions. lOMoARcPSD|45316467

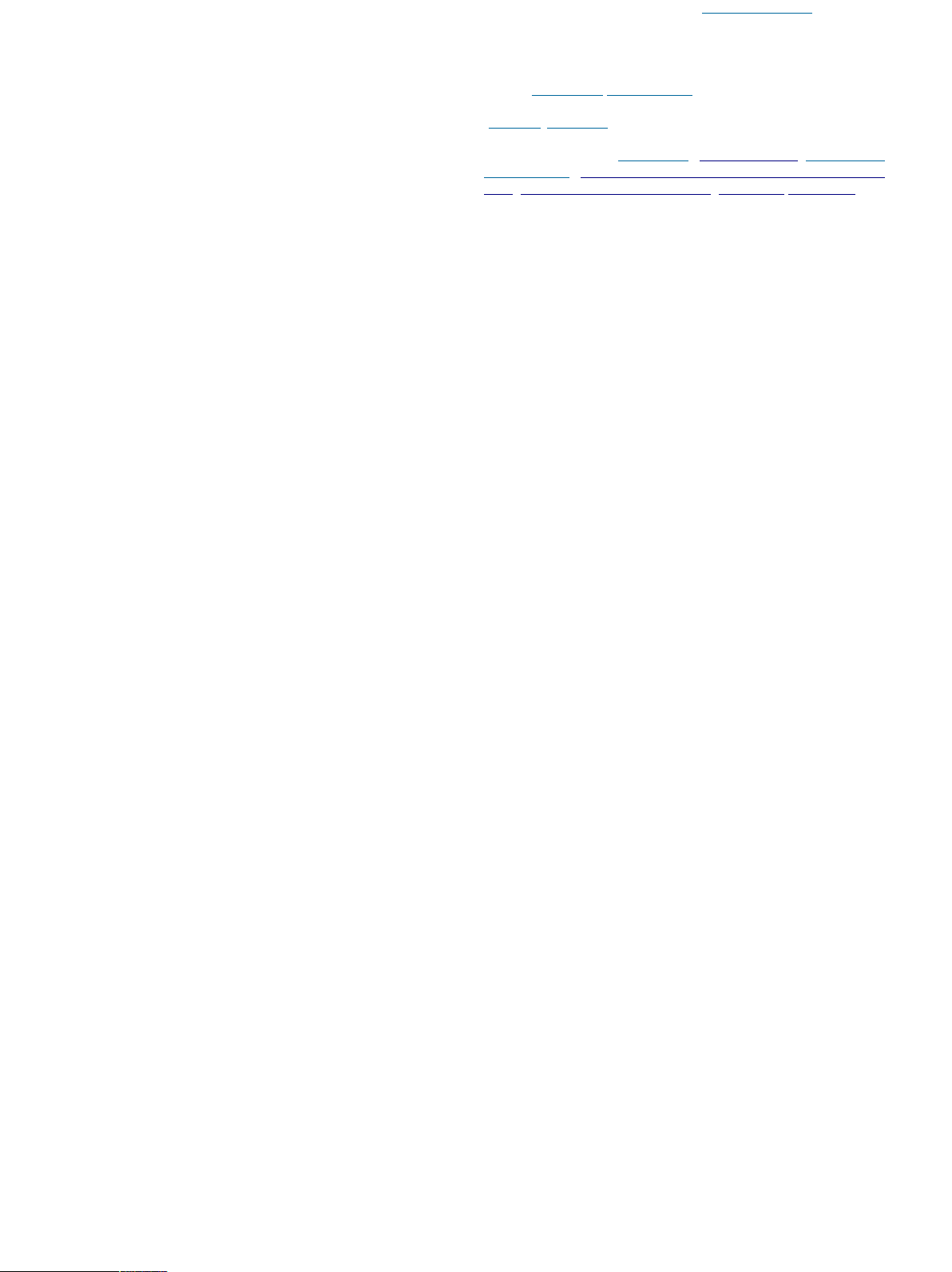

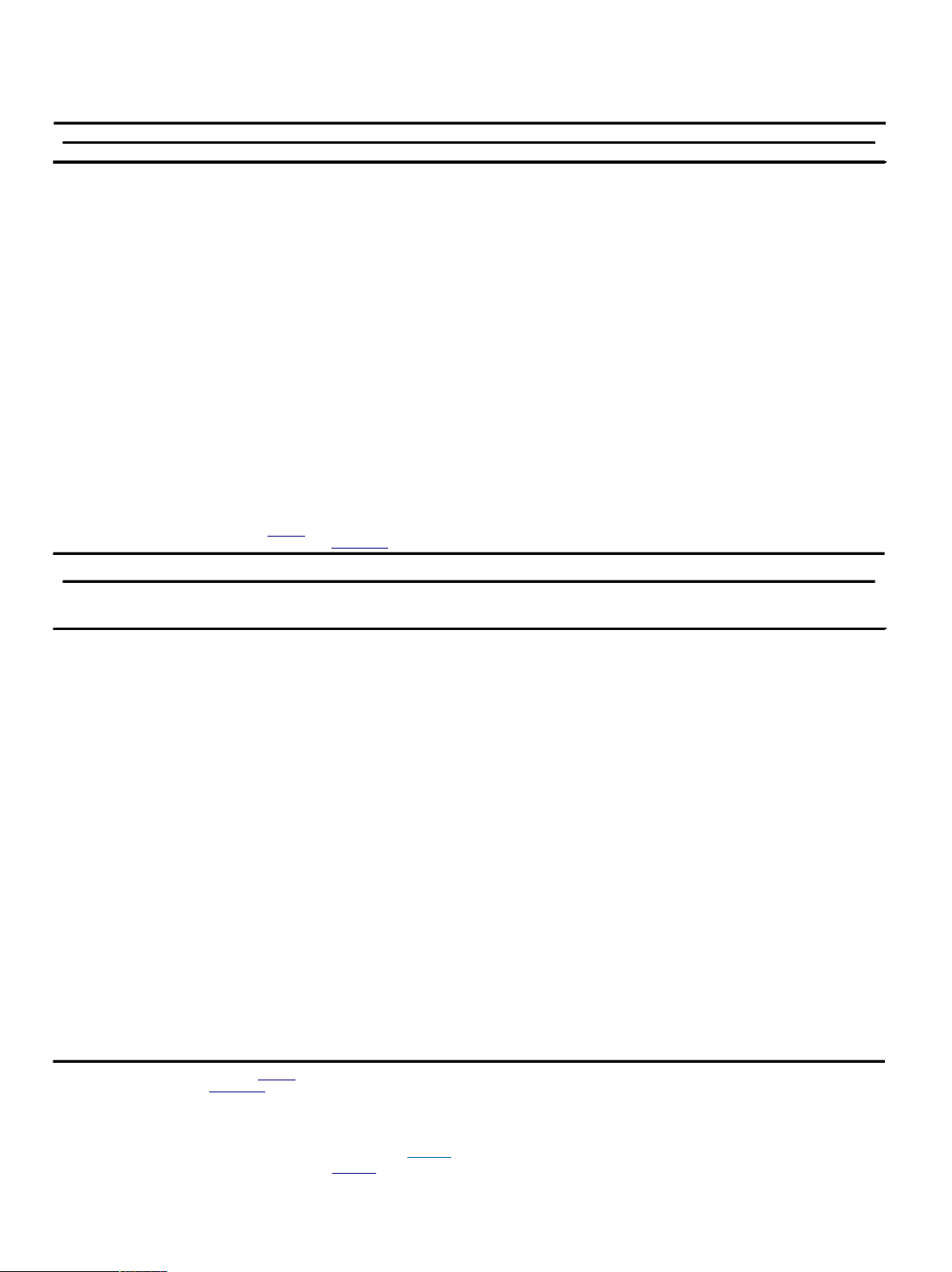

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827 821 Table 2

Comparison of dividend-paying firms and non–dividend-paying firms. Paying firms Nonpaying firms

Mean differences (t-statistic)

(dividends > 0; N = 8114)

(dividends = 0; N = 6592) Mean Median SD Mean Median SD Dividend 0.019 0.013 0.017 0.000 0.000 0.000 87.500*** Foreign shareholder 0.167 0.000 0.373 0.078 0.000 0.269 16.275*** Foreign share 0.003 0.000 0.009 0.001 0.000 0.007 11.464*** Market to book 2.931 2.251 2.232 3.969 2.570 5.439 15.639*** Firm size 22.004 21.847 1.258 21.163 21.079 1.136 42.107*** Cash holding 0.181 0.151 0.122 0.133 0.107 0.107 25.092*** ROE 0.105 0.092 0.071 0.003 0.027 0.317 29.727*** Leverage 0.471 0.481 0.184 0.598 0.576 0.308 31.004*** Intangible 0.040 0.025 0.052 0.052 0.030 0.065 12.713*** Managerial 0.039 0.000 0.114 0.016 0.000 0.076 13.761*** State-owned 0.671 1.000 0.470 0.617 1.000 0.486 6.802***

*** Denote significance at the 0.1% level. See A

ppendix A for variable definitions.

the state, as the ultimate controlling shareholder of many firms in

by dividend (models 1 and 2) and dividend payer (models 3 and 4).

China, tends to press for higher cash dividends in order to reduce the

Because dividend is censored at zero for firms that do not pay

free cash flows under managers’ discretion. On the other hand, state-

dividends, we use tobit regression models for examining the impact of

owned firms have political objectives to satisfy and may not monitor

foreign ownership on dividend yield. Tobit regression uses a maximum

managers based on the achievement of value-maximizing objectives

likelihood estimation designed for situations in which the dependent

(Ben-Nasr, 2015; Firth et al., 2016). According to agency theory,

variable is constrained in some way (Amemiya, 1984). Moreover, we

managers of state-owned firms may have incentives to keep cash

run probit regression models when dividends are measured by dividend

within the firm for their own benefits. Consistent with the predictions of

payer, which takes the value of one if the company pays dividends in

agency theory, Ben-Nasr (2015), using a sample of newly privatized

the particular year, and zero otherwise. Foreign shareholding is

firms from 43 countries, find evidence that dividend payout is

measured by Foreign shareholder (models 1 and 3) and Foreign share

negatively related to government ownership. Thus, similar to previous

(models 2 and 4). All regressions include year dummies and industry

studies (Ben-Nasr, 2015; Firth et al., 2016), we control for State-owned,

dummies. Similar to previous dividend studies (Adjaoud & Ben-Amar,

which is a dummy variable equal to one if the firm is ultimately

2010; Baba, 2009), all regressions reported in our main analysis are

controlled by the state. Finally, we include year and industry dummies.

estimated using random effects to adjust standard errors for clustering

Our industry controls are based on the 13-industry official classification at the firm level.

announced in 2001 by the Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). T

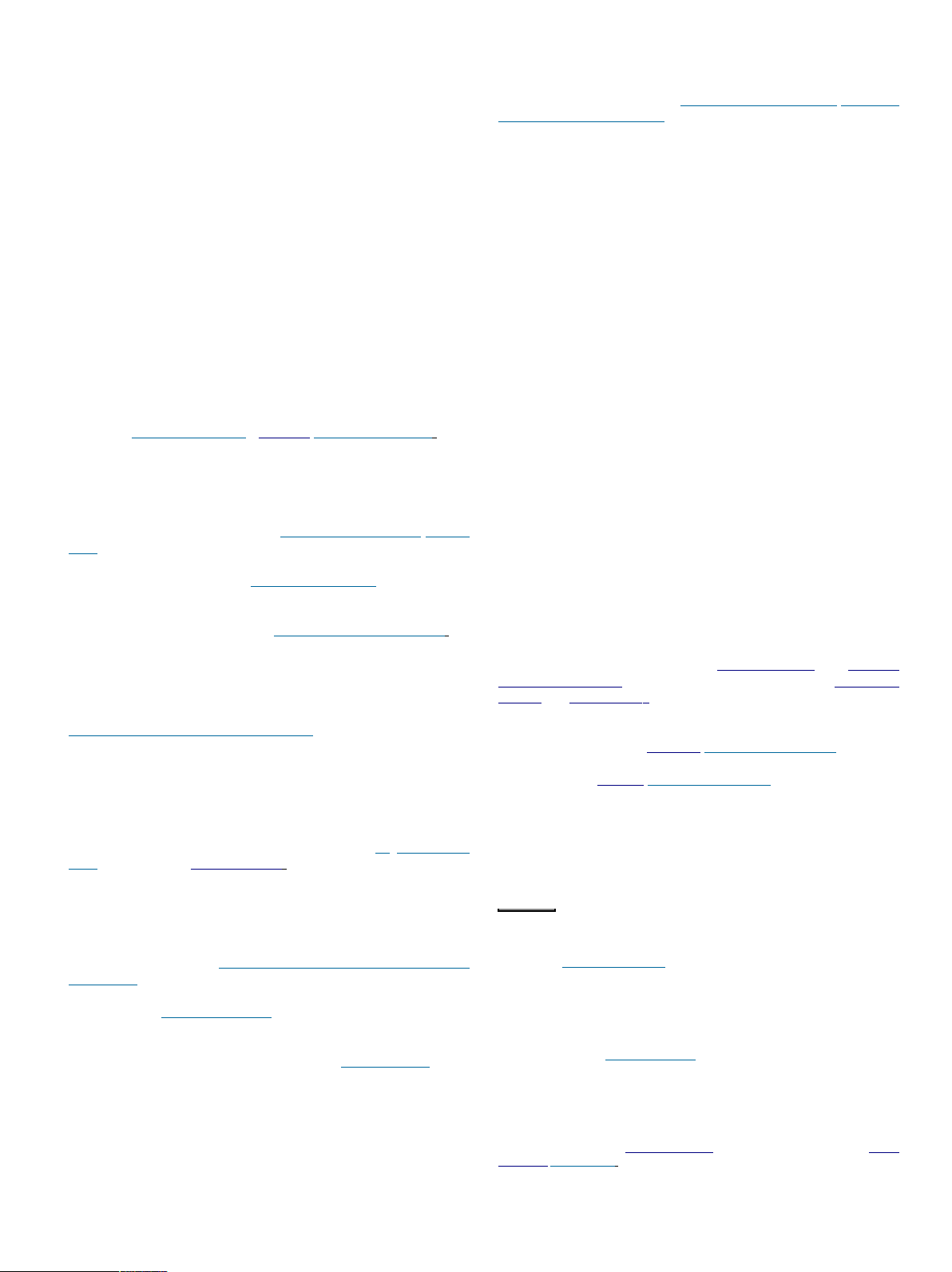

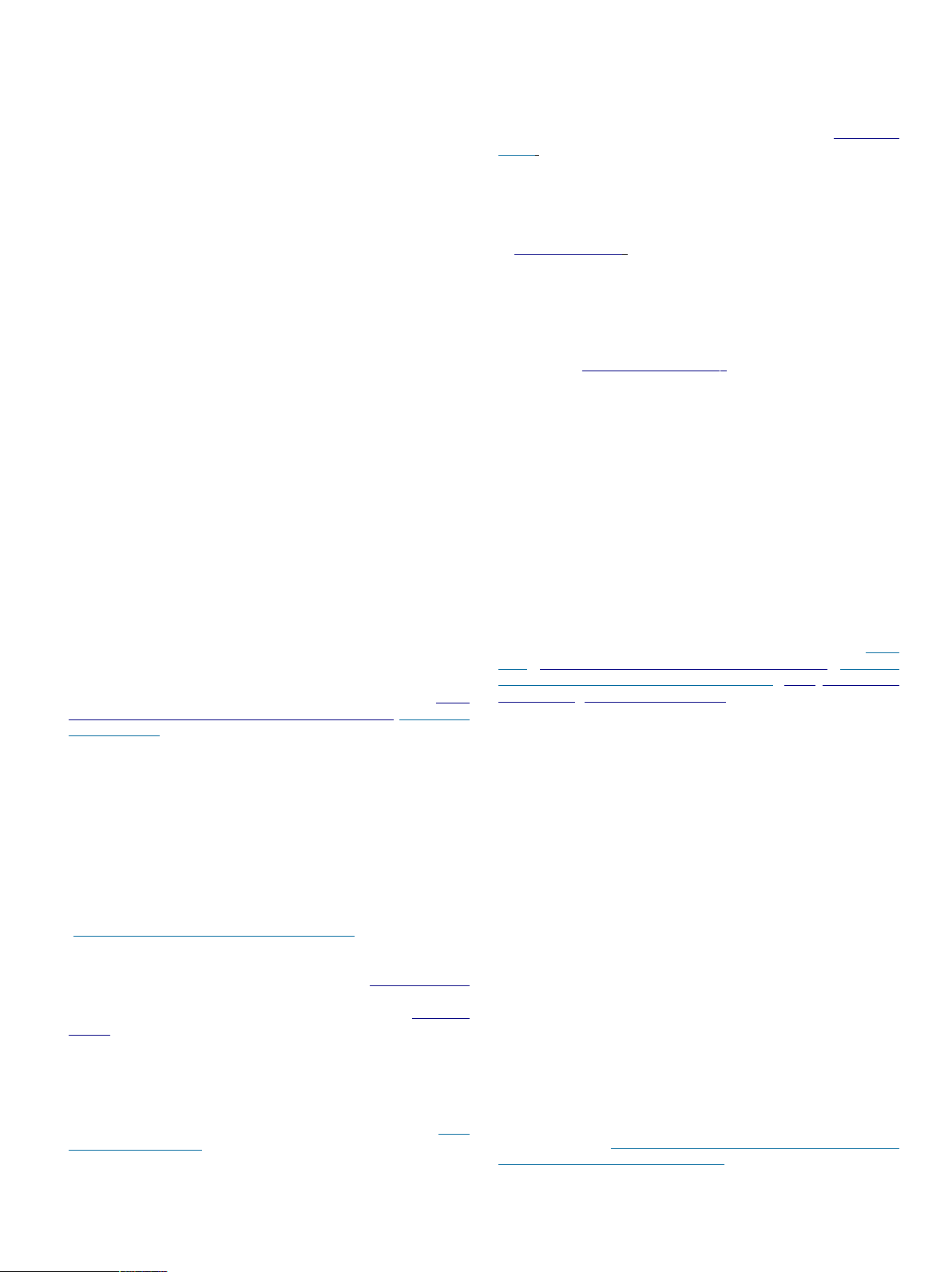

able 3 reports the regression results. Models 1 and 2 use dividend,

while models 3 and 4 use dividend payer to measure a 5. Results

5.1. Descriptive statistics Table 3

Foreign shareholding and dividend policy. T

able 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlations for the data Dependent variables Dividend Dividend payer

set. Among our firm-year observations,12.7% have at least one foreign Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

institutional investor among the ten largest shareholders. Firms pay Foreign shareholder 0.002*** 0.172**

dividends in 55.2% of the observations, and the mean dividend to total (3.508) (3.241)

asset ratio is 0.1%. As expected, the firm’s dividend policy (as Foreign share 0.088*** 6.024*

evidenced by dividend and dividend payer) is positively correlated with (4.246) (2.430)

foreign shareholdings. Moreover, all the variance inflation factors (VIF) Market to book 0.000 0.000 0.026*** 0.025*** ( 0.642) ( 0.629) ( 3.598) ( 3.531)

of our explanatory variables are below 2, indicating that Firm size 0.007*** 0.007*** 0.798*** 0.802***

multicollinearity is not a problem. Table 2 compares dividend-paying (25.402) (25.549) (26.488) (26.709)

and non–dividend-paying firms. As one would expect, non–dividend- Cash holding 0.021*** 0.021*** 1.410*** 1.399***

paying firms are much less profitable, hold less cash and smaller in (11.903) (11.906) (7.633) (7.584)

size than dividend-paying firms. Non–dividend-paying firms also have ROE 0.062*** 0.062*** 3.625*** 3.625*** (38.257) (38.204) (25.034) (25.029)

significantly less foreign ownership, but higher leverage and more Leverage 0.060*** 0.060*** 3.709*** 3.720***

growth potential than dividend-paying firms. ( 43.077) ( 43.195) ( 26.086) ( 26.180) Intangible 0.017*** 0.017*** 1.912*** 1.920*** ( 4.261) ( 4.252) ( 4.745) ( 4.766)

5.2. Regression models examining the association between foreign Managerial 0.028*** 0.028*** 2.580*** 2.579*** (9.629) (9.657) (8.740) (8.741)

shareholding and dividends State-owned 0.000 0.000 0.025 0.027 (0.020) (0.091) (0.405) (0.442)

We first investigate whether there is a significant association Year dummies Included Included Included Included

between foreign shareholding and dividends using the following Industry dummies Included Included Included Included equation: Wald chi-square statistic 19094*** 19097*** 1625*** 1623*** No. of observations 14706 14706 14706 14706

Dividend j;t ¼ G0þg1Foreign shareholdingj;tþControlsj;t

This table presents the regression results for dividend policy and foreign shareholding.

þ Dummy ðindustry; yearÞ þ e

Tobit regression models were used for examining the impact of foreign ownership on j;t ð1Þ

Dividend, while probit regression models were used for examining the impact of foreign

where j stands for the jth firm and t for time. Controls stand for all the

ownership on Dividend payer. *, **, *** denote significance at the 5%, 1%, and 0.1%

control variables. e is the error term. Dividends are measured

levels, respectively. T-statistics are reported in parentheses. See A ppendix A for variable definitions. lOMoARcPSD|45316467 822

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827

firm’s dividend policy. As shown in models 1 and 2, Chinese listed

variable in the system to receive the prediction of the endogenous

firms pay higher dividends when foreign institutional investors are

variables. The values of partial R2 of excluded instruments are 0.349

present and when such investors hold more shares. Models 3 and 4

and 0.350 for Foreign share and Dividend respectively. The F-statistic is

suggest that Chinese listed firms are more likely to pay dividends

3559 (p = 0.00) for Foreign share and 3550 (p = 0.00) for Dividend,

when foreign institutional investors are present and when such

showing the strength of the instruments. In addition, Pagan-Hall

investors hold more shares. All of this evidence supports a positive

general test statistics are significant (2343.893,

association between foreign institutional shareholding and divi-dend

p = 0.00; 2054.937, p = 0.00 for Foreign share and Dividend

payments. Results for control variables are generally consistent with

respectively), suggesting the presence of heteroscedasticity. Thus, we

prior literature on dividend policy (see Baker, 2009; for a

use GMM estimation which uses a weighting matrix taking account of

comprehensive overview). We find that firms are more likely to pay

temporal dependence, heteroskedasticity or autocorre-lation (Hansen,

dividends and to pay higher dividends when they are larger and when

1982). We tried to measure dividends in different ways (i.e. dividend;

they have larger cash and better past perfor-mance. Firms are less

dividend yield; dividend payout). However, Hansen J statistic tests on the

likely to pay dividends when their financial leverage is higher and when

appropriateness of over-identifying restrictions are clearly

they have potential growth opportunities, as evidenced by larger

unsatisfactory when dividend yield and dividend payout were used.

intangible assets and higher market-to-book value. Finally, there is a

Therefore, we use dividend, and Foreign share in our simultaneous

positive association between managerial ownership and dividend

equation models. Hansen J statistic tests of both equations show that

payments, indicat-ing that entrenched managers prefer dividend

overidentifying restrictions are valid (1.915, p = 0.167; 0.316, p = 0.574 payments than capital gains.

for equations 2 and 3 respectively), thus all the instruments identify the

same vector of parameters (Parentea & Silvac, 2012). Table 4 presents the results.

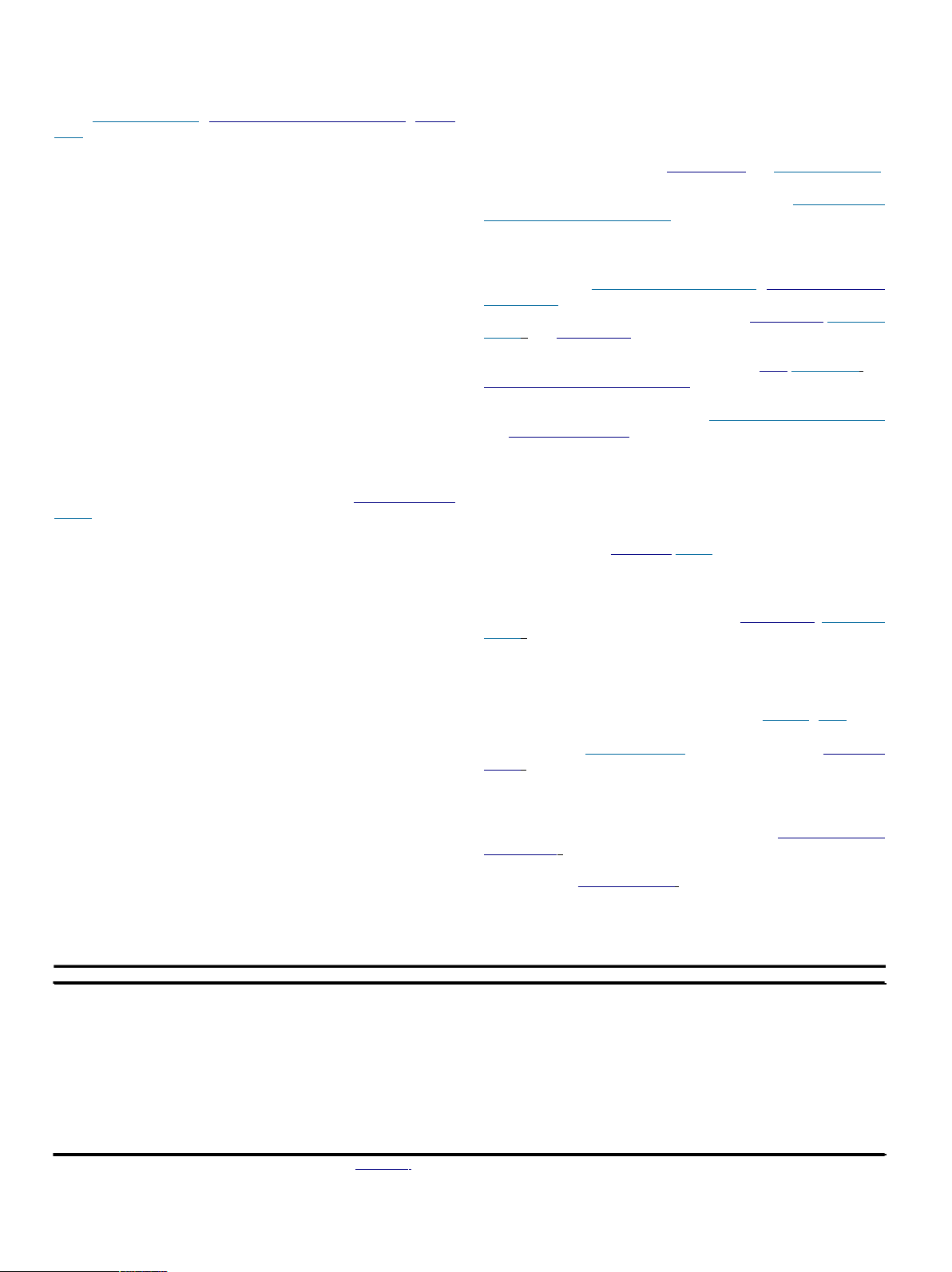

5.3. Simultaneous equation models

We find that firms with higher foreign shareholding pay more

dividends and vice versa. This indicates that foreign institutional

An important concern is the endogeneity problem arising from

investors choose to invest in firms with higher dividends, and their

omitted firm-specific variables that are likely to impact both foreign

shareholdings can promote the firms’ dividend payments. There-fore,

shareholding and dividend policy. To deal with the potential

foreign institutional investors’ investment choices and Chinese listed

endogeneity, we investigate the interrelationship be-tween foreign

firms’ dividend decisions may be jointly determined and influence each

shareholding and dividends in a system of two equations: other in a positive manner.

5.4. Changes in foreign shareholding and changes in dividends

Dividendj;t ¼ A0;jþa1;jForeign shareholdingj;tþa2;jDividendj;t 1

þ a3;jInvestmentj;t 1 þ Controlsj;t þ Hj;t

Another important concern is whether foreign shareholding ð2Þ

changes drive dividend changes or the reverse holds true. To address

this issue, we study the relationship between the changes

Foreign shareholdingj;t ¼ B0;jþb1;jDividendj;t Table 4

þb2;jForeign shareholdingj;t 1 þ b3;jIndexj;t 1 þ Controls

Results of GMM of a simultaneous equation system model. j;t þ E Dependent variables Dividend Foreign share j;t ð3Þ

where j stands for the jth firm and t for time. Controls stand for all the Model 1 Model 2

control variables discussed above. The error terms for the two Foreign share j,t 0.070**

equations are H and E respectively. Each equation contains one of our (2.994)

endogenous variables as dependent variable, and the other one as Dividend j,t 1 0.495***

explanatory variable, along with exogenous variables and control (34.703)

variables. In addition to lag-terms of the dependent variables, we Foreign share j,t 1 0.588*** (16.900)

incorporate lagged investment (Investmentj,t-1) into dividend decisions, Dividend j,t 0.059***

and lagged Marketization Index of the province where a firm is (6.201) Market to book registered (Index j,t 0.000* 0.000

j,t-1) into foreign shareholding decisions. The finance (1.972) ( 0.039)

literature suggests that firms with higher investment in tangible assets Firm size j,t 0.001*** 0.000***

experience higher earnings subse-quently, leading to higher dividend (8.075) (3.385)

payments (see Lee, Liang, Lin, & Y ang, 2016 for a summary). Cash holding j,t 0.011*** 0.001 (9.597) ( 1.826)

Investment is measured by net property, plant and equipment over total ROE

assets, obtained from the Chinese CSMAR database. Marketization j,t 0.006*** 0.000 (17.786) (0.087)

Index (Index) is widely used to measure the financial development of Leverage j,t 0.008*** 0.000*

provinces in China based on five indicators: the role of government, ( 19.236) (2.562)

economic structure, free inter-regional trade, development of factor Intangible j,t 0.000 0.001

market, and legal framework (Fan et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016). We ( 0.164) (0.961)

choose this variable as an instrument because a rich province may Managerial j,t 0.004** 0.001* (2.614) ( 2.462)

attract more foreign institutional investors as they are able to offer State-owned j,t 0.000 0.000

generous fiscal incentives to foreign investors with more capital left at ( 0.160) (1.179) their disposal. Year dummies Included Included Industry dummies Included Included

Following Lee et al. (2016), we perform the first-stage F-statistic to R2 0.494 0.369 No. of observations 13296 13213

test whether our instruments are weak and then examine the presence of heteroscedasticity using P

agan and Hall (1983)’s test. The

This table presents the GMM regression results of a simultaneous equation system model for

exogenous variables are regressed on each endogenous

Dividend and Foreign share. *, **, *** denote significance at the 5%, 1%, and

0.1% levels, respectively. T-statistics are reported in parentheses. See A ppendix A for variable definitions. lOMoARcPSD|45316467

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827 823

in dividend policy and the changes in foreign shareholdings. This

negative impact on the subsequent changes in the ratio of dividends to

approach eliminates the impacts of time-invariant and unobserv-able total assets.

firm characteristics on the dependent variable, and has been deployed

Models 5–8 conduct change regressions in the reverse direction to

in finance studies (Aggarwal et al., 2011; Firth et al., 2016; Grinstein &

examine if firms with higher dividend payments will attract more foreign

Michaely, 2005). Following the research design used in Firth et al.

shareholding. The dependent variable is the change in a firm’s foreign

( 2016) and Aggarwal et al. (2011), we estimate the following

shareholding from time t-1 to t, where foreign shareholding is equations:

measured by Foreign shareholder and Foreign share. The independent D

and control variables are the same as in Table 3, but measured by

Dividendj t ¼ G0þg1DForeign shareholdingj t 1þDControlsj t 1

changes from time t-2 to t-1. If firms that proactively increase their ; ; ;

þ Dummy ðindustry; yearÞ þ Zj t 1

dividends attract more foreign share-holders, the coefficient of the ; ð4Þ

lagged change in dividends (l1) should be significantly different from

zero, while the same is not true for the coefficient of the lagged change

of foreign shareholding (g1). The results show that the lagged change

DForeign shareholdingj t ¼ L0þL1DDividendj t 1þDControlsj t 1

of Dividend payer is not significant to the subsequent change of foreign ; ; ;

þ Dummy ðindustry; yearÞ þ Uj t 1

shareholding (models 5 and 6). However, models 7 and 8 of Table 5 ; ð5Þ

show that the changes in Dividend from time t 2 to t 1 is significant to

the changes in both Foreign shareholder and Foreign share from time

where j stands for the jth firm and t for time. Controls stand for all

the control variables. Z and U are error terms. T able 5 presents the t

1 to t. These results are more in line with the signaling perspective empirical results. In T

able 5 models 1–4, the dependent variable is the

that firms attract foreign shareholders by paying more dividends.

change in a firm’s dividend policy from time t 1 to t, where dividend

policy is measured by Dividend (models 1 and 3) and Dividend payer

(models 2 and 4). The research variables and control variables are the 5.5. Robustness tests

same as in Table 3, but measured by changes from time t-2 to t-1. If

the increase of foreign shareholding promotes the firm’s subsequent

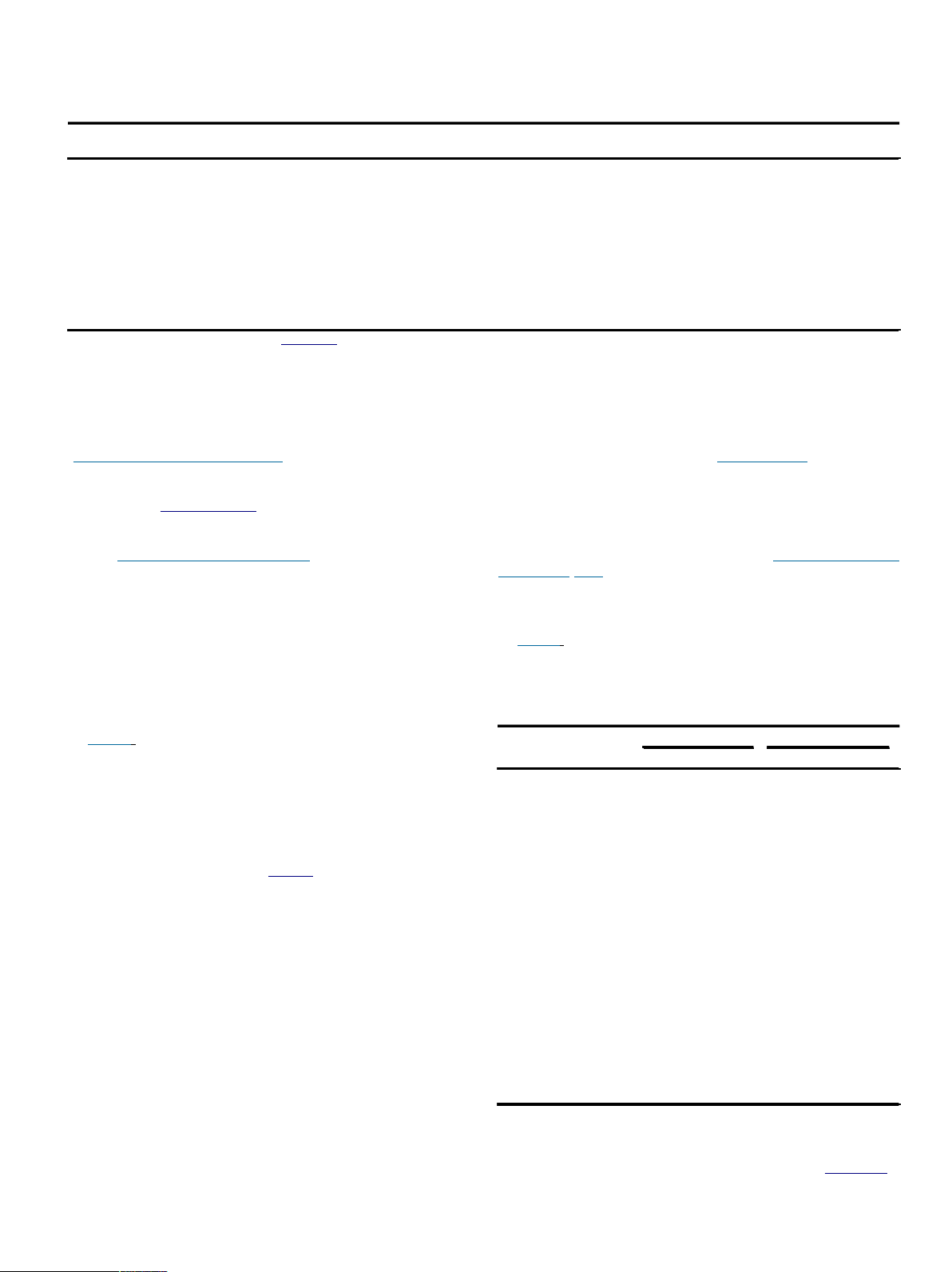

dividend payments, we would expect the coefficient of the lagged

In this section, we perform a variety of robustness checks of our

main findings. We first check the sensitivity of the results presented in

change of foreign ownership (G1) to be positive and significantly T

able 5 using an alternative measurement of foreign institutional

different from zero, while the same is not true for the coefficient of the

holding, which is a dummy variable (High foreign) equal to one if the

lagged change of dividend (L1). T

able 5 models 1, 3 and 4 show that

foreign ownership of a given firm is higher than our sample median

the changes in foreign shareholding have no impact on the

foreign ownership and zero otherwise. Second, we estimate

subsequent changes in dividend-paying behavior. Furthermore, as

regression models with respect to the relationship between changes in

shown in model 2 of Table 5, the changes in the presence of foreign

dividends and changes in foreign shareholding shareholder have a Table 5

Changes in foreign shareholding and changes in dividends. Dependent variables D(Dividend D(Dividend) D(Dividend D(Dividend) D(Foreign D(Foreign D(Foreign D(Foreign Payer) Payer) Shareholder) Share) Shareholder) Share) Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6 Model 7 Model 8 D(Foreign Shareholder j, 0.004 0.001* ) t 1 ( 0.311) ( 2.433) D(Dividend Payer j,t 1) 0.011 0.000 (1.279) (1.874) D(Foreign Share j,t 1) 0.621 0.037 (1.139) ( 1.769) D(Dividend j,t 1) 0.936* 0.021** (2.462) (2.792) D(Market to book j,t 1) 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 (0.463) (0.957) (0.460) (0.906) (0.305) (1.591) (0.294) (1.587) D(Firm Size j,t 1) 0.015 0.001 0.015 0.001 0.007 0.000 0.009 0.000 ( 1.233) ( 1.914) ( 1.215) ( 1.955) (0.696) ( 0.642) (0.844) ( 0.400) DCash holding j,t 1) 0.048 0.006*** 0.048 0.006*** 0.007 0.000 0.015 0.000 (0.843) (3.337) (0.835) (3.345) ( 0.156) ( 0.154) ( 0.328) ( 0.374) D(ROE j,t 1) 0.004 0.000 0.004 0.000 0.012 0.000 0.011 0.000 ( 0.609) (0.345) ( 0.603) (0.306) (1.573) ( 0.024) (1.414) ( 0.142) D(Leverage j,t 1) 0.002 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.000 0.009 0.001 ( 0.056) (1.147) ( 0.041) (1.147) (0.036) (0.639) (0.362) (0.955) D(Intangible j,t 1) 0.177 0.005 0.178 0.005 0.078 0.001 0.076 0.001 (1.610) (1.360) (1.621) (1.382) (0.686) (0.582) (0.662) (0.554) D(Managerial j,t 1) 0.748** 0.000 0.749** 0.000 0.074 0.001 0.069 0.001 (3.102) ( 0.612) (3.107) ( 0.621) ( 0.412) (0.447) ( 0.384) (0.499) D(State-owned j,t 1) 0.002 0.024*** 0.002 0.024*** 0.002 0.000 0.002 0.000 ( 0.088) (3.436) ( 0.097) (3.421) ( 0.117) (0.015) ( 0.122) (0.155) Year Dummies Included Included Included Included Included Included Included Included Industry Dummies Included Included Included Included Included Included Included Included N 11480 11449 11480 11449 11492 11492 11492 11492 Wald chi2 182.376*** 120.153 183.162*** 118.884 189.419*** 127.345*** 190.483*** 129.840***

This table presents the regression results for the relationship between changes in dividend policy and changes in foreign shareholding. *, **, *** denote significance at the 5%, 1%,

and 0.1% levels, respectively. T-statistics are reported in parentheses. See A

ppendix A for variable definitions. lOMoARcPSD|45316467 824

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827 Table 6

Panel A: Robustness check using alternative measures of foreign shareholding. Dependent variables D(Dividend Payer) D(Dividend) D(High Foreign) D(High Foreign) Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 D(High Foreign j,t 1) 0.016 0.001 (0.936) ( 0.881) D(Dividend Payer j,t 1) 0.007 (1.261) D(Dividend j,t 1) 0.663* (2.228) D(Market to book j,t 1) 0.000 0.000 0.001* 0.001* (0.450) (0.922) (2.224) (2.207) D(Firm Size j,t 1) 0.015 0.001 0.005 0.004 ( 1.215) ( 1.937) ( 0.740) ( 0.581) D(Cash Flow j,t 1) 0.048 0.006*** 0.031 0.037 (0.842) (3.329) ( 1.003) ( 1.179) D(ROE j,t 1) 0.004 0.000 0.006 0.005 ( 0.609) (0.323) (1.160) (0.983) D(Leverage j,t 1) 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.005 ( 0.044) (1.159) ( 0.039) (0.356) D(Intangible j,t 1) 0.178 0.005 0.047 0.045 (1.618) (1.388) (0.666) (0.643) D(Managerial j,t 1) 0.749** 0.024*** 0.031 0.035 (3.105) (3.426) (0.279) (0.313) D(State-owned j,t 1) 0.002 0.000 0.006 0.006 ( 0.093) ( 0.632) (0.461) (0.457) Year Dummies Included Included Included Included Industry Dummies Included Included Included Included N 11480 11449 11492 11492 Wald chi2 182.498 115.935 150.183 152.215

This table presents the robustness check of T

able 5 using alternative measures of foreign shareholding. *, **, *** denote significance at the 5%, 1%, and 0.1% levels,

respectively. T-statistics are reported in parentheses. See A

ppendix A for variable definitions.

Panel B: Robustness check using alternative measures of dividend Dependent variables D (Dividend D(Dividend D (Dividend D(Dividend D(Foreign D(%Foreign D(Foreign D(%Foreign Payout) yield) Payout) yield) Shareholder) Shares) Shareholder) Shares) Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6 Model 7 Model 8 D(Foreign 0.011 0.001*** Shareholder j,t 1) ( 1.359) ( 3.727) D(Dividend Payout j, 0.024* 0.000 ) t 1 (2.014) (1.844) D(% Foreign Shares j, 0.069 0.042* ) t 1 ( 0.163) ( 2.409) D(Dividend yield j,t 1) 1.048* 0.037*** (2.439) (3.859) D(Market to book j, 0.001 0.000 0.001 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 ) t 1 ( 1.697) ( 0.586) ( 1.726) ( 0.661) (0.343) (1.609) (0.314) (1.599) D(Firm Size j,t 1) 0.011 0.000 0.011 0.000 0.008 0.000 0.007 0.000 ( 1.646) ( 1.263) ( 1.655) ( 1.316) (0.784) ( 0.494) (0.690) ( 0.768) D(Cash Flow j,t 1) 0.016 0.003 0.016 0.003 0.008 0.000 0.010 0.000 ( 0.407) (1.952) ( 0.410) (1.959) ( 0.185) ( 0.173) ( 0.223) ( 0.316) D(ROE j,t 1) 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.013 0.000 0.011 0.000 (0.008) ( 1.768) ( 0.005) ( 1.805) (1.682) (0.063) (1.419) ( 0.263) D(Leverage j,t 1) 0.037* 0.001 0.037* 0.001 0.001 0.000 0.004 0.000 ( 2.004) (0.970) ( 1.996) (0.969) (0.044) (0.629) (0.162) (0.883) D(Intangible j,t 1) 0.169* 0.003 0.171* 0.003 0.079 0.001 0.072 0.001 (2.219) (0.993) (2.231) (1.024) (0.696) (0.585) (0.634) (0.483) D(Managerial j,t 1) 0.591*** 0.000 0.591*** 0.000 0.069 0.001 0.002 0.000 (3.640) ( 0.090) (3.638) ( 0.105) ( 0.383) (0.482) ( 0.115) (0.029) D(State-owned j,t 1) 0.017 0.015** 0.017 0.015** 0.002 0.000 0.074 0.001 (1.153) (2.926) (1.142) (2.912) ( 0.112) (0.015) ( 0.407) (0.457) Year Dummies Included Included Included Included Included Included Included Included Industry Dummies Included Included Included Included Included Included Included Included N 11450 11480 11450 11480 11492 11492 11492 11492 Wald chi2 263.568 1037.571*** 262.556 1053.978*** 190.279 127.945 191.456*** 129.851***

This table presents the robustness check of T

able 5 using alternative measures of dividends. *, **, *** denote significance at the 5%, 1%, and 0.1% levels, respectively. T-statistics

are reported in parentheses. See A

ppendix A for variable definitions.

using alternative measures of dividend policy: dividend payout and

analyze the relationship between changes in foreign shareholding and

dividend yield. The results of all these analyses (presented in Table 6)

changes in dividends, which assume that firm specific effects are

are in line with the previous results reported in Table 5. Third, in the

uncorrelated with independent variables. As the variable “State-

main analyses we use random effects models to

owned” in the regressions is almost completely time- lOMoARcPSD|45316467

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827 825

invariant, we could not estimate fixed effect models. As a robustness

In 2005 the CSRC launched a process of converting nontradable

check, we leave out the variable “State-owned” and estimate fixed

shares into tradable shares, with the end goal of abolishing the

effect models. We also run the regressions without assuming random

nontradable share category entirely by the end of 2006. Chen et al.

effects using robust standard errors to assess the significance of the

( 2009) study the period 1990 to 2004 and note that during that period,

estimated coefficients. The results (available from the corresponding

shares held by governments and state agencies are usually

author) are similar to those reported in the main analyses. Finally, we

nontradable. Thus, controlling shareholders would sometimes prefer

rerun our main analyses using only those firms for which we have data

high dividends as a means of diverting part of the proceeds from

for all the years (2003–2013). The results are consistent.

overpriced IPOs or secondary offerings to themselves since they were

not able to achieve this by selling shares. While we find the arguments of C

hen et al. (2009) intriguing, our sample period starts from 2003,

6. Conclusion and discussion

when controlling shareholders knew that their nontradable shares

would likely become tradable before long, which would limit their

This study investigates the relationship between dividend policy

incentive to pay high dividends for expropriation purposes. Dividends

and foreign institutional shareholding in Chinese listed firms. Using the

are, after all, a relatively inefficient means of expropriation since they

GMM method to deal with the potential endogeneity between foreign

must be shared with minority shareholders.

shareholding and dividends, our simultaneous equations results show

that foreign shareholding influences dividend payments, and vice Moreover, H

uang and Zhu (2015) suggest that QFIIs are more

versa. This finding implies that Chinese listed firms can use dividends

likely than local mutual funds to perform arm’s-length negotiation and

to signal growth opportunities and attract foreign institutional investors.

monitoring in the process of the share structure reform that floats

Foreign institutional investors can also promote dividends in the firms

formerly nontradable shares, to the benefit of all minority shareholders.

in which they hold shares. These findings seem to support dividend

By contrast, we do not find much evidence that foreign institutional

policy explanations from both agency and signaling perspectives.

investors actively increase dividends by changing their shareholdings.

This could be an indication that controlling shareholders expropriate

Furthermore, we investigate whether changes in foreign

wealth from minority share-holders (foreign institutions) once they

institutional ownership over time positively affect subsequent changes

have invested in the firm, which is a significant agency problem in

in dividend payments, or vice versa. We find that changes in dividend

developing countries such as China. Furthermore, foreign

payments over time drive subsequent changes in foreign shareholding,

shareholding and dividend decisions seem to be jointly determined

but that the opposite does not hold true. This seems to support the

and interact with each other in a positive manner. While we make no

signaling perspective, which posits that firms attract foreign investment

claim to know the ultimate truth about the role of foreign institutional

by using dividends to signal their commitment to protecting minority

investors in China, we believe our study is valuable because it

shareholder rights in the absence of effective institutional protections.

provides a different view from the current orthodoxy.

Thus, the changes in foreign institutional investors’ shareholding do

not have much impact on the changes in firms’ dividend policy, but

From a broader perspective, our findings add to the small literature

instead foreign institutional investors self-select into Chinese firms that

on the impact of foreign shareholding in emerging markets (Baba,

already pay high dividends. This finding is in contrast to prior studies of

2009; Buckley, Munjal, Enderwick, & Forsans, 2015; Desender,

emerging markets which suggest that foreign institutional investors

Aguilera, Lópezpuertas-Lamy, & Crespi, 2014; Jeon, Cheolwoo, &

play an active role in enhancing corporate governance (e.g., Baba,

Moffett, 2011; Kim, Sul, & Kang, 2010) by showing that institutional

2009; Desender et al., 2014; Huang & Zhu, 2015; Jeon et al., 2011;

context matters when it comes to predicting the impact of foreign

Kim et al., 2010). One possible explanation is that QFIIs are investors

institutional investment in emerging markets. Sophisticated foreign

who have gone through an application process to obtain special

institutional investors do not automatically play a role in enhancing

permission to invest in domestically listed Chinese firms. This sets

corporate governance; whether they play such a role depends on the

China apart from other Asian markets such as South Korea and

institutional framework within which they make their investment.

Japan, where foreigners can invest more freely. The skewed power

balance resulting from the QFII system possibly places foreign minority

Our empirical findings have practical implications for Chinese listed

shareholders in a submissive role in corporate governance, with the

firms, foreign investors, and policymakers in China. We provide

result that they have little impact on the firm’s future dividends.

evidence that foreign institutional investors tend to prefer to invest in

firms that already pay higher dividends. This should be of interest to

firms that wish to raise funds from foreign providers of finance. Al else

So far research has focused primarily on the role of institutional

equal, firms can attract foreign institutional investment through the

investors in the U.S. and developed markets, with mixed results

signaling value of their dividend policy. In particular, for the majority of

(Grinstein & Michaely, 2005; Short et al., 2002). Although China's

Chinese listed firms that are ultimately controlled by the state, dividend

economy has been growing rapidly and many institutional investors

payouts may be used to signal that their privatization has been

have invested in Chinese listed firms, less attention has been paid to

successful. By the same token the results have implications for foreign

the role of institutional investors in China. Recently, Firth et al. (2016)

institutional investors. We show that foreign institutional investors

find that only one class of institutional investors mutual funds influence

investing in China assign a positive value to generous dividends;

firms to pay higher cash dividends. Our study complements Firth et al.

however, it is difficult for them to change firms’ future dividend

( 2016) by showing that the locations of institutional investors matter in

payments once they have made their investment choices in China.

explaining firms’ dividend policy, in addition to the types of institutional

Thus, it is important for foreign institutional investors to collect and

investors. Specifically, foreign institutional investors already investing

analyze firm-specific information concerning governance quality when

in Chinese listed firms under the quota scheme seem to have difficulty

carrying out stock valuation in China. Finally, this study provides

influencing Chinese listed firms to pay higher cash dividends by

implications for policy makers. If policymakers want sophisticated

changing their shareholding, probably because of their limited

foreign institutional investors to use their expertise to enhance the

shareholding and the high information asymmetry they face (Leuz,

corporate governance of Chinese listed firms, as they do in other

Lins, & Warnock, 2009). Instead, they are attracted to firms that pay

emerging markets (Baba, 2009; Desender et al., 2014; Huang & Zhu, high dividends to begin with.

2015; Jeon et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2010), they may consider relaxing lOMoARcPSD|45316467 826

L. Cao et al. / International Business Review 26 (2017) 816–827

the restrictions on foreign portfolio investment so that foreign (Continued)

institutions have more bargaining power in mitigating agency problems Variables Definitions in Chinese listed firms. Dividend

This study is subject to a number of limitations that open up payout

avenues for future research. First, the sample period of this study Dividend yield

Common dividends over market value of equity

starts from 2003, when China partially opened its domestic stock Foreign

A dummy variable equal to 1 if at least one of the largest 10

market to foreign institutional investors. Our time horizon is relatively shareholder

shareholders is foreign (including Hong Kong and Taiwan), and 0 otherwise

short, thus the findings may not represent the long-run behavior of the Foreign share

The proportion of shares held by the foreign shareholders

observed relationships. Second, although we controlled for the High foreign

A dummy equal to 1 if the foreign ownership by QFII of a given

potential endogeneity using the GMM method for a system of two

firm is higher than the sample median foreign ownership and

equations, our endogenous variables (i.e., Dividend; Foreign share) are 0 otherwise

censored, and coefficients based on GMM may be biased (Rigobon & Market to book

The ratio of the market value of equity to the book value of equity

Stoker, 2009). Moreover, in the analysis of the relationship between Firm size

The natural logarithm of total assets

changes in foreign share-holding and changes in dividends, we cannot Cash holding

Cash and cash equivalents divided by total assets

rule out the possibility that some of the lagged variables on the right- Leverage

Total liabilities divided by total assets

hand side are correlated with the disturbances, which may lead to ROE The after-tax return on equity

endogeneity bias. Third, this study focuses only on dividend policy and Intangible

Intangible assets divided by total assets Managerial

The proportion of managerial shares

foreign shareholdings. As foreign portfolio investment in China State-owned

A dummy variable equal to 1 if the firm is ultimately control ed

continues to grow in pace with the steady liberalization of the Chinese by the state

capital markets, future research should examine more Investment

Net property, plant and equipment over total assets, obtained

comprehensively the linkages between foreign ownership and the

from the Chinese CSMAR database. Index

Marketization Index widely used to measure the financial

performance, policies, and practices of Chinese listed firms. In

development of provinces in China based on five indicators:

particular, it would be interesting to examine whether the heterogeneity

the role of government, economic structure, free inter-

of firm-level corporate governance quality (e.g., as evidenced by board

regional trade, development of factor market, and legal

composition) influences the role of foreign institutional investors in

framework (Fan et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016).

Chinese listed firms. Moreover, future research could explore the

impact of foreign institutional investment on other governance issues

such as tunneling by controlling shareholders, earnings quality, and

executive compen-sation. Fourth, we restrict our analysis to Chinese References

listed firms, and the extent to which our findings can be generalized to

firms in other emerging markets may be limited. A comparative study

Adjaoud, F., & Ben-Amar, W. (2010). Corporate governance and dividend policy:

incorporating data from different developing countries could enhance S

hareholders’ protection or expropriation? J ournal of Business Finance & A

ccounting , 3 7 ( 5–6), 648–667 .

our understanding of the role of foreign institutional investors. Finally,

Aggarwal, R., Erel, I., Ferreira, M., & Matos, P. (2011). Does governance travel around

future research could differentiate in more detail between different th

e world? Evidence from institutional investors. J ournal of Financial Economics , 1 00 ,

types of listed firms and examine the role of foreign shareholding in, 154–181.

for example, family firms, and multina-tional companies.

Agrawal, A., & Jayaraman, N. (1994). The dividend policies of al -equity firms: A direct te

st of the free cash flow theory. M

anagerial and Decision Economics , 1 5 ( 2), 139– 148.

Ahmadjian, C. L., & Robbins, G. E. (2005). A clash of capitalism: Foreign shareholders a

nd corporate restructuring in 1990 Japan. A

merican Sociological Review , 7 0 ( 3), 451–472. A

memiya, T. (1984). Tobit models: A survey. J ournal of Econometrics , 2 4 ( 1–2), 3–61 . Acknowledgements

Baba, N. (2009). Increased presence of foreign investors and dividend policy of J apanese firms. P

acific-Basin Finance Journal , 1 7 , 1 63–174 . B

aker, H. K. (Ed.), (2009). Div

idends and dividend policy. kolb series in finance .

We are grateful to editor, Pervez Ghauri and two anonymous

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

reviewers for their insightful feedback during the review process. We

Ben-Nasr, H. (2015). Government ownership and dividend policy: Evidence from newly

thank Ilan Alon, Christof Beuselinck, Igor Filatotchev, Niels Hermes, p

rivatised firms. J ournal of Business Finance & Accounting , 4 2 ( 5–6), 665– 704.

Minna Martikainen-Peltola, Lars Oxelheim, Trond Randøy, and

Berkman, H., Cole, R. A., & Fu, J. L. (2009). Expropriation through loan guarantees to

Francisco Santos, Laurence van Lent, Arnt Verriest, Milos Vulanovic

r elated parties: Evidence from China. J ournal of Banking and Finance , 3 3 , 1 41– 156.

for their valuable comments and suggestions. Earlier versions of this

paper were presented at the 5th NFB Research School Conference in

Buckley, P. J., Munjal, S., Enderwick, P., & Forsans, N. (2015). Do foreign resources

assist or impede internationalisation? Evidence from internationalisation of Indian

Stavanger, Norway (2013), the 40th EIBA Annual Conference in m

ultinational enterprises. I nternational Business Review [A rticle in press] .

Uppsala, Sweden (2014), the 32nd FIBE Conference in Bergen,

Buckley, P. J. (1997). Cooperative form of transnational corporation activity. In J. H.

Norway (2015), the 41st EIBA Annual Conference in Rio de Janeiro, Du

nning, & K. P. Sauvant (Eds.), T

ransnational corporations and world d evelopment

(pp. 473–493).Thomson: London.

Brazil (2015), the 3rd IB Finance workshop at WU Vienna, Austria

Chen, G., Firth, M., Gao, D. N., & Rui, O. M. (2006). Corporate performance and CEO

(2016), and the research seminar of EDHEC Business School in Lille

c ompensation in China. J ournal of Corporate Finance , 1 2 , 6 93–714 .

(2016). The authors are grateful to the National Natural Science

Chen, D., Jian, M., & Xu, M. (2009). Dividends for tunneling in a regulated econ:omy: T he case of China. P

acific-Basin Finance Journal , 1 7 , 2 09–223 .

Foundation of China (No. 71502055

Chen, Q., Chen, X., Schipper, K., Xu, Y., & Xue, J. (2012). The sensitivity of corporate

& No. 71572054), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the

c ash holdings to corporate governance. R

eview of Financial Studies , 2 5 ( 12), 3610–

Central Universities of China (No.531107050726). 3644.

Cheung, Y. L., Jing, L., Lu, T., Rau, P. R., & Stouraitis, A. (2009). Tunneling and

propping up: An analysis of related party transactions by Chinese listed

Appendix A. Variable definitions companies. P

acific-Basin Finance Journal , 1 7 , 3 72–393 .

Claessens, S., & Fan, J. P. H. (2002). Corporate governance in asia: A survey.

I nternational Review of Finance , 3 ( 2), 71–103 . Variables Definitions

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Lang, L. H. P. (2000). The separation of ownership and Dividend