Preview text:

20 PART V: LONG-TERM FINANCING Raising Capital

On May 18, 2012, in a long-awaited initial public offering

social media platform Weibo went public at a price of $17.

(IPO), social network Facebook went public at a price of

The stock price jumped to $20.24 at the end of the day, a

$38 per share. The stock price opened trading at $42.05 19.1 percent increase.

before quickly fal ing back to $38. To the surprise of many,

Businesses large and smal have one thing in common:

the stock closed at $38.23, barely unchanged from its IPO

They need long-term capital. This chapter describes how

price. Over the next few trading days, investors turned

they get it. We pay particular attention to what is prob-

antisocial and unfriended the stock, sending it tumbling to

ably the most important stage in a company’s financial life

$32 per share. In contrast, when Twitter went public on

cycle—the IPO. Such offerings are the process by which

November 7, 2013, at a price of $26, investors went #crazy.

companies convert from being privately owned to publicly

The stock quickly jumped to a high of $50.09, before closing

owned. For many people, starting a company, growing it,

the first day at $44.90. Then, on April 17, 2014, Chinese

and taking it public is the ultimate entrepreneurial dream.

This chapter examines how firms access capital in the real world. The financing method is

generally tied to the firm’s life cycle. Start-up firms are often financed via venture capital.

As firms grow, they may want to “go public.” A firm’s first public offering is called an

IPO, which stands for initial public offering. Later offerings are called SEOs for seasoned

equity offerings. This chapter follows the life cycle of the firm, covering venture capital,

IPOs, and SEOs. Debt financing is discussed toward the end of the chapter.

20.1 Early-Stage Financing and Venture Capital

One day, you and a friend have a great idea for a new computer software product that will

help users communicate using the next-generation meganet. Filled with entrepreneurial

zeal, you christen the product Megacomm and set about bringing it to market.

Working nights and weekends, you are able to create a prototype of your product. It

doesn’t actually work, but at least you can show it around to illustrate your idea. To actu-

ally develop the product, you need to hire programmers, buy computers, rent office space,

and so on. Unfortunately, because you are both MBA students, your combined assets are

not sufficient to fund a pizza party, much less a start-up company. You need what is often

referred to as OPM—other people’s money.

Your first thought might be to approach a bank for a loan. You would probably

discover, however, that banks are generally not interested in making loans to start-up 617

618 ■■■ PART V Long-Term Financing

companies with no assets (other than an idea) run by fledgling entrepreneurs with no track

record. Instead you search for other sources of capital.

One group of potential investors goes by the name of angel investors, or just angels.

They may just be friends and family, with little knowledge of your product’s industry and

little experience backing start-up companies. However, some angels are more knowledgeable

individuals or groups of individuals who have invested in a number of previous ventures. VENTURE CAPITAL

Alternatively, you might seek funds in the venture capital (VC) market. While the term

venture capital does not have a precise definition, it generally refers to financing for new,

often high-risk ventures. Venture capitalists share some common characteristics, of which

three1 are particularly important:

1. VCs are financial intermediaries that raise funds from outside investors. VC firms are

typically organized as limited partnerships. As with any limited partnership, limited

partners invest with the general partner, who makes the investment decisions. The lim-

ited partners are frequently institutional investors, such as pension plans, endowments,

and corporations. Wealthy individuals and families are often limited partners as well.

This characteristic separates VCs from angels, since angels typically invest just

their own money. In addition, corporations sometimes set up internal venture capital

divisions to fund fledgling firms. However, Metrick and Yasuda point out that, since

these divisions invest the funds of their corporate parent, rather than the funds of

others, they are not—in spite of their name—venture capitalists.

2. VCs play an active role in overseeing, advising, and monitoring the companies in which

they invest. For example, members of venture capital firms frequently join the board of

directors. The principals in VC firms are generally quite experienced in business. By

contrast, while entrepreneurs at the helm of start-up companies may be bright, creative,

and knowledgeable about their products, they often lack much business experience.

3. VCs generally do not want to own the investment forever. Rather, VCs look for an

exit strategy, such as taking the investment public (a topic we discuss in the next

section) or selling it to another company. Corporate venture capital does not share

this characteristic, since corporations are frequently content to have the investment

stay on the books of the internal VC division indefinitely.

This last characteristic is quite important in determining the nature of typical VC

investments. A firm must be a certain size to either go public or be easily sold. Since the

investment is generally small initially, it must possess great growth potential; many busi-

nesses do not. For example, imagine an individual who wants to open a gourmet restaurant.

If the owner is a true “foodie” with no desire to expand beyond one location, it is unlikely

the restaurant will ever become large enough to go public. By contrast, firms in high-tech

fields often have significant growth potential and many VC firms specialize in this area.

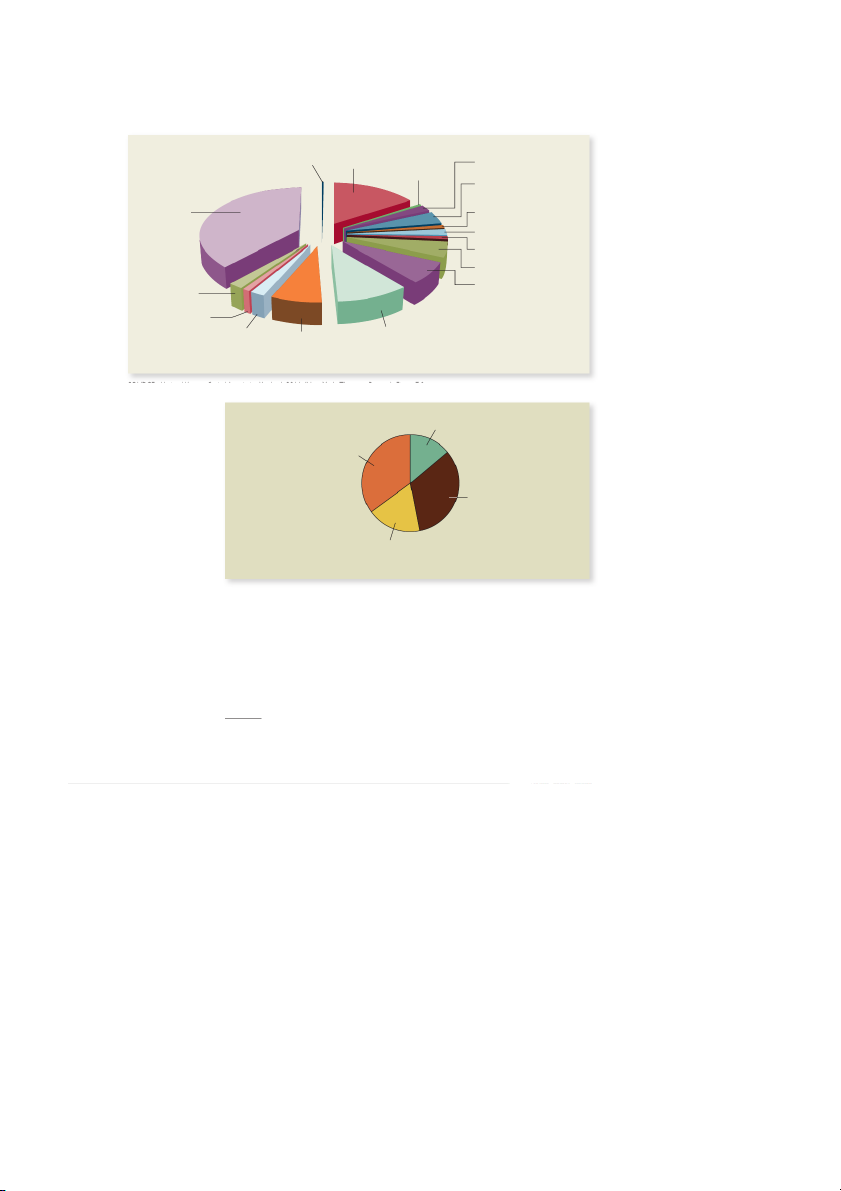

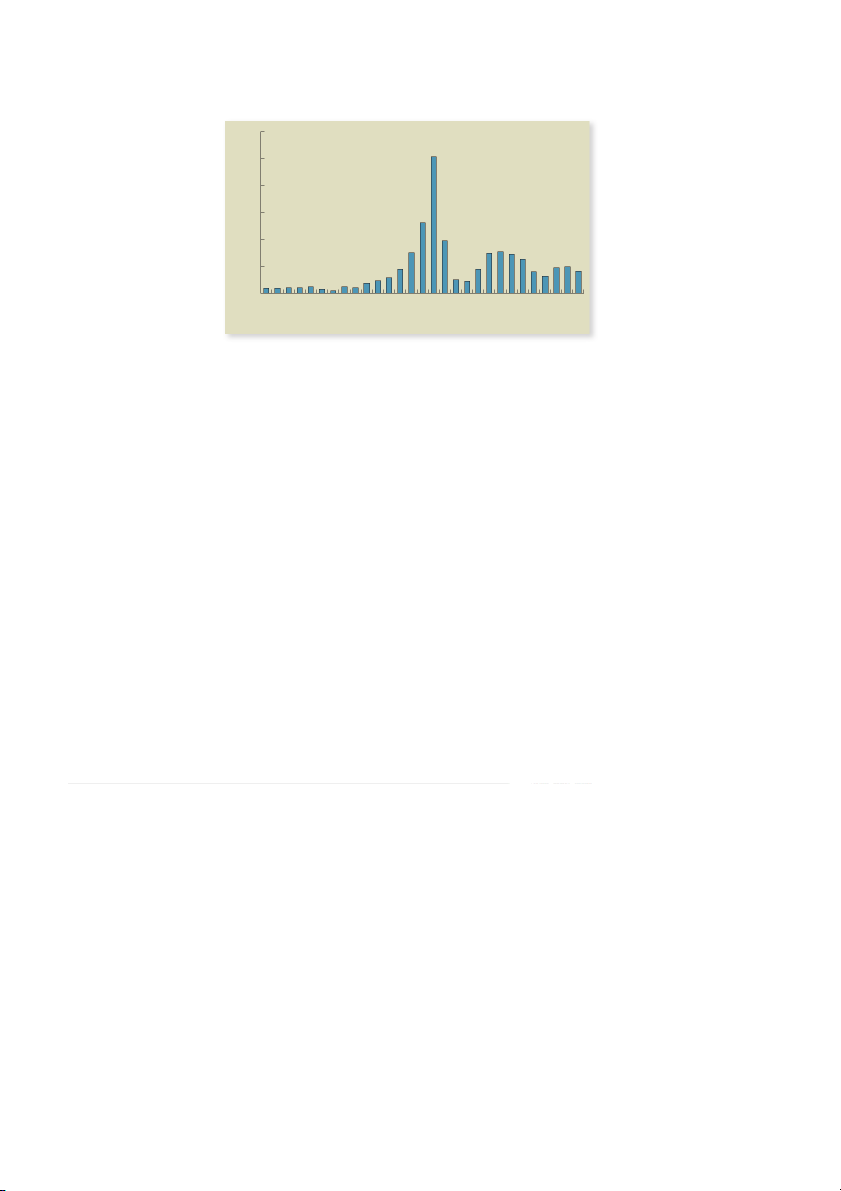

Figure 20.1 shows VC investments by industry. As can be seen, a large percentage of these

investments are in high-tech fields.

How often do VC investments have successful exits? While data on exits are difficult

to come by, Figure 20.2 shows outcomes for more than 11,000 companies funded in the

1990s. As can be seen, nearly 50 percent (514% 1 33%) went public or were acquired.

However, the Internet bubble reached its peak in early 2000, so the period covered in the

table may have been an unusual one.

1These characteristics are discussed in depth in Andrew Metrick, and Ayako Yasuda, Venture Capital and the Finance

of Innovation, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, 2011).

CHAPTER 20 Raising Capital ■■■ 619

Figure 20.1 Venture Capital Investments in 2013 by Industry Sector Other Biotechnology Business Computers and .2% 15% Products and Peripherals 2% Services .4% Consumer Products and Services 4% Software Electronics/ Instrumentation 1% 37% Financial Services 2% Healthcare Services 1% Industrial/Energy 5% Semiconductors IT Services 7% 2% Retailing/ Distribution 1% Networking and Medical Devices Media and Equipment and Equipment Entertainment 2% 7% 10%

SOURCE: National Venture Capital Association Yearbook 2014, (New York: Thomson Reuters), Figure 7.0. Figure 20.2 Went/Going Public The Exit Funnel 14% Outcomes of the 11,686 Companies Still Private First Funded 1991 or Unknown* to 2000 35% Acquired 33% Known Failed 18%

*Of these, most have quietly failed.

SOURCE: National Venture Capital Association Yearbook 2014, (New York: Thomson Reuters). STAGES OF FINANCING

Both practitioners and scholars frequently speak of stages in venture capital financing.

Well-known classifications for these stages are2:

1. Seed money stage: A small amount of financing needed to prove a concept or

develop a product. Marketing is not included in this stage.

2. Start-up: Financing for firms that started within the past year. Funds are likely to

pay for marketing and product development expenditures.

2Albert V. Bruno and Tyzoon T. Tyebjee, “The Entrepreneur’s Search for Capital,” Journal of Business Venturing (Winter 1985);

see also Paul Gompers and Josh Lerner, The Venture Capital Cycle (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

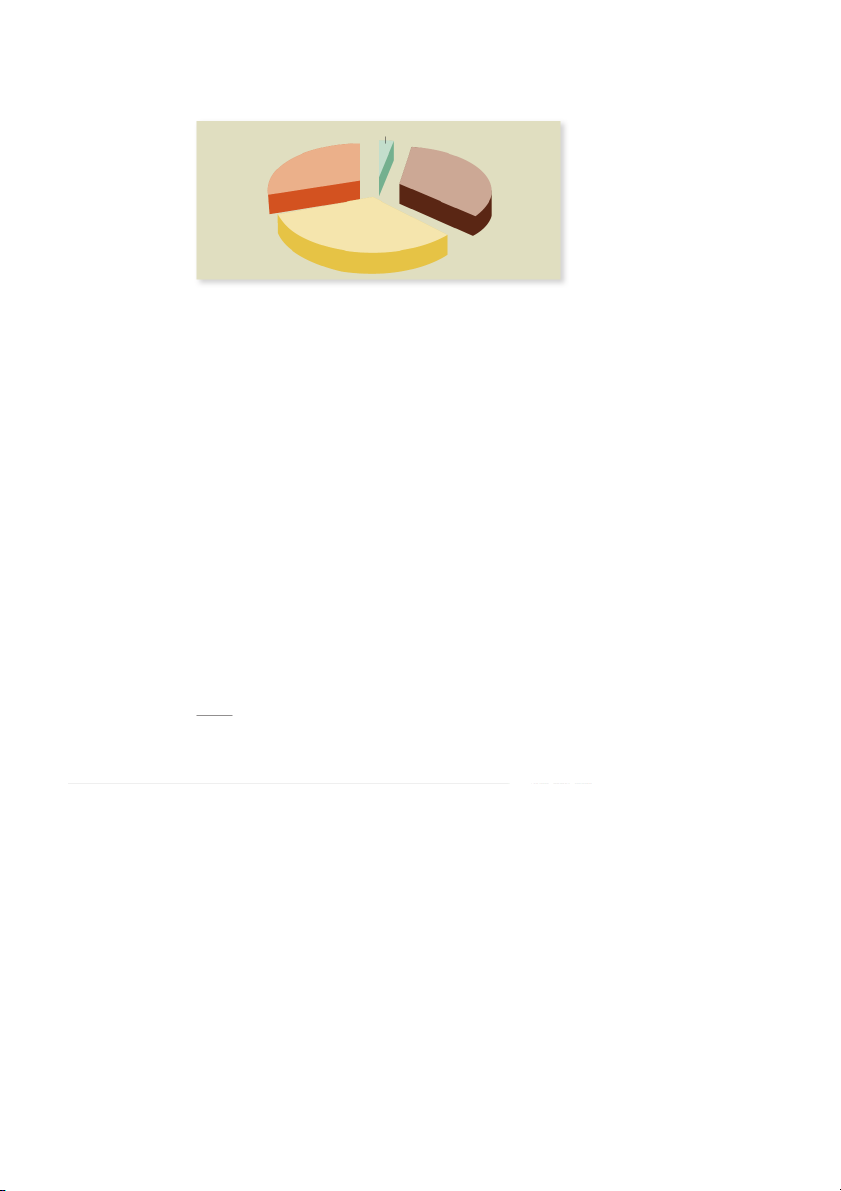

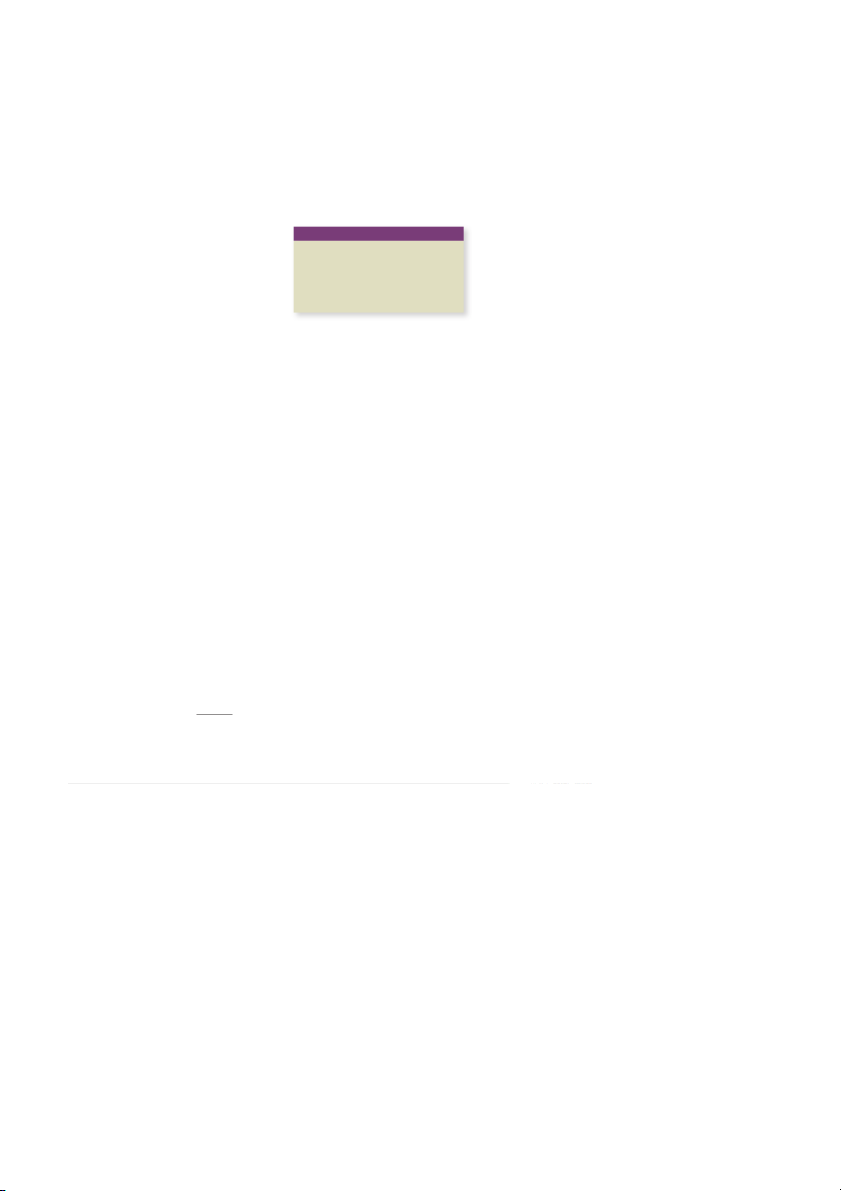

620 ■■■ PART V Long-Term Financing Figure 20.3 Seed 3% 2013 Venture Capital Investment by Company Stage Later Stage Early Stage 30% 34% Expansion 33%

SOURCE: National Venture Capital Association Yearbook 2014, (New York: Thomson Reuters), Figure 6.0.

3. First-round financing: Additional money to begin sales and manufacturing after a

firm has spent its start-up funds.

4. Second-round financing: Funds earmarked for working capital for a firm that is cur-

rently selling its product but still losing money.

5. Third-round financing: Financing for a company that is at least breaking even and is

contemplating an expansion. This is also known as mezzanine financing.

6. Fourth-round financing: Money provided for firms that are likely to go public within

half a year. This round is also known as bridge financing.

Although these categories may seem vague to the reader, we have found that the terms are

well-accepted within the industry. For example, the venture capital firms listed in Pratt’s

Guide to Private Equity and Venture Capital Sources3 indicate which of these stages they are interested in financing.

Figure 20.3 shows venture capital investments by company stage. The authors of this

figure use a slightly different classification scheme. Seed and Early Stage correspond to

the first two stages above. Later Stage roughly corresponds to Stages 3 and 4 above and

Expansion roughly corresponds to Stages 5 and 6 above. As can be seen, venture capitalists

invest little at the Seed stage. SOME VENTURE CAPITAL REALITIES

Although there is a large venture capital market, the truth is that access to venture capital

is very limited. Venture capital companies receive huge numbers of unsolicited proposals,

the vast majority of which end up unread in the circular file. Venture capitalists rely heav-

ily on informal networks of lawyers, accountants, bankers, and other venture capitalists to

help identify potential investments. As a result, personal contacts are important in gaining

access to the venture capital market; it is very much an “introduction” market.

Another simple fact about venture capital is that it is quite expensive. In a typical

deal, the venture capitalist will demand (and get) 40 percent or more of the equity in the

company. Venture capitalists frequently hold voting preferred stock, giving them various

priorities in the event the company is sold or liquidated. The venture capitalist will typi-

cally demand (and get) several seats on the company’s board of directors and may even

appoint one or more members of senior management.

3Shannon Pratt, Guide to Private Equity and Venture Capital Sources (New York: Thompson Reuters, 2014).

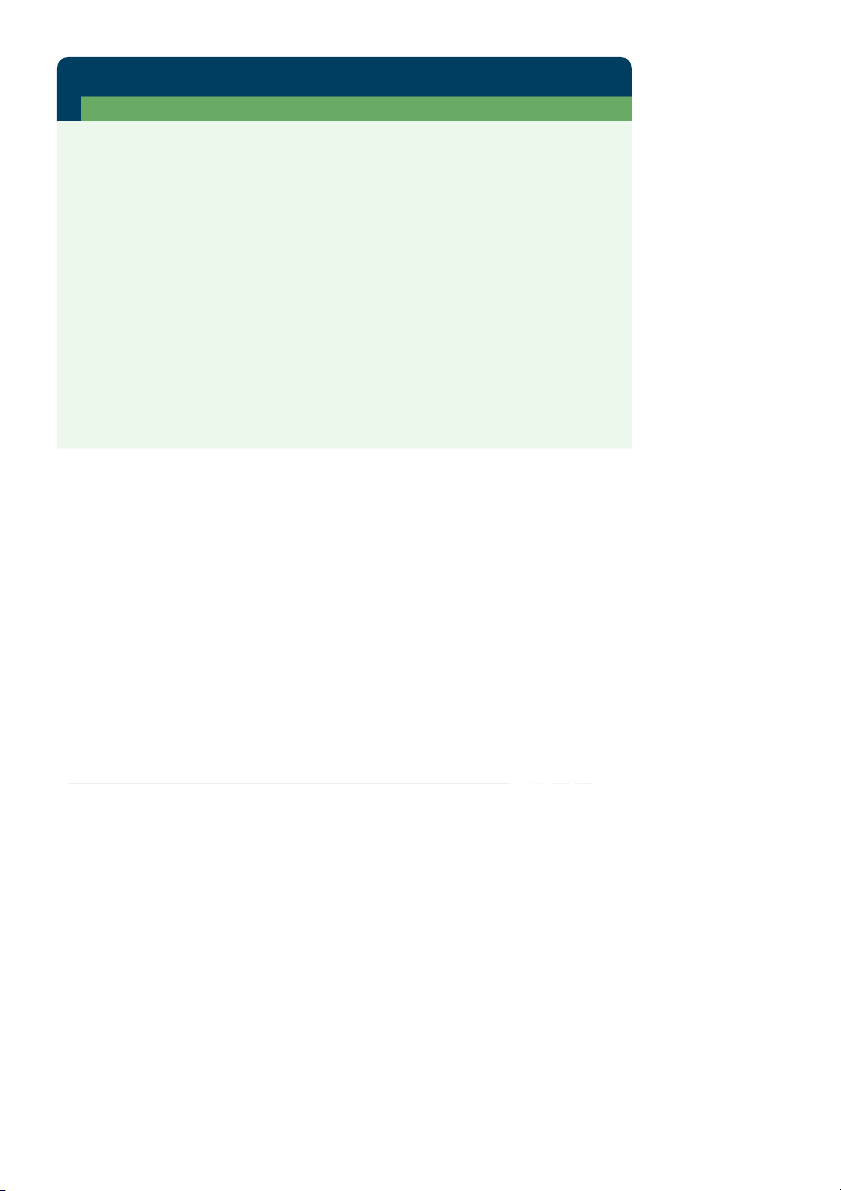

CHAPTER 20 Raising Capital ■■■ 621 Figure 20.4 120 Capital Commitments to U.S. Venture Funds 100 ($ in bil ions) 1985 to 2013 80 ) 60 illions ($ B 40 20 0

19851986198719881989199019911992199319941995199619971998199920002001200220032004200520062007200820092010201120122013 Year

SOURCE: National Venture Capital Association Yearbook 2014, (New York: Thomson Reuters), Figure 3.0.

VENTURE CAPITAL INVESTMENTS AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONS

Venture capital investments are strongly influenced by economic conditions. Figure 20.4

shows capital commitments to U.S. venture capital firms over the period from 1985

to 2013. Commitments were essentially flat from 1985 to 1993 but rose rapidly

during the rest of the 1990s, reaching their peak in 2000 before falling precipitously. To

a large extent, this pattern mirrored the Internet bubble, with prices of high-tech stocks

increasing rapidly in the late 1990s, before falling even more rapidly in 2000 and 2001.

This relationship between venture capital activity and economic conditions continued

in later years. Commitments rose during the bull market years between 2003 and 2006,

before dropping from 2007 to 2010 in tandem with the more recent economic crisis. 20.2 The Public Issue

If firms wish to attract a large set of investors, they will issue public securities. There

are a lot of regulations for public issues, with perhaps the most important established in

the 1930s. The Securities Act of 1933 regulates new interstate securities issues and the

Securities Exchange Act of 1934 regulates securities that are already outstanding. The

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) administers both acts.

The basic steps for issuing securities are:

1. In any issue of securities to the public, management must first obtain approval from the board of directors.

2. The firm must prepare a registration statement and file it with the SEC. This state-

ment contains a great deal of financial information, including a financial history,

details of the existing business, proposed financing, and plans for the future. It can

easily run to 50 or more pages. The document is required for all public issues of

securities with two principal exceptions:

a. Loans that mature within nine months.

b. Issues that involve less than $5 million.

622 ■■■ PART V Long-Term Financing

The second exception is known as the small-issues exemption. Issues of less

than $5 million are governed by Regulation ,

A for which only a brief offering

statement—rather than the full registration statement—is needed.

3. The SEC studies the registration statement during a waiting period. During this

time, the firm may distribute copies of a preliminary prospectus. The preliminary

prospectus is called a red herring because bold red letters are printed on the cover.

A prospectus contains much of the information put into the registration statement,

and it is given to potential investors by the firm. The company cannot sell the securi-

ties during the waiting period. However, oral offers can be made.

A registration statement will become effective on the 20th day after its filing

unless the SEC sends a letter of comment suggesting changes. After the changes are

made, the 20-day waiting period starts anew.

4. The registration statement does not initially contain the price of the new issue. On

the effective date of the registration statement, a price is determined and a full-

fledged selling effort gets under way. A final prospectus must accompany the deliv-

ery of securities or confirmation of sale, whichever comes first.

5. Tombstone advertisements are used during and after the waiting period. An example is reproduced in Figure 20.5.

The tombstone contains the name of the issuer (the World Wrestling Federation, now

known as World Wrestling Entertainment). It provides some information about the issue,

and lists the investment banks (the underwriters) involved with selling the issue. The role

of the investment banks in selling securities is discussed more fully in the following pages.

The investment banks on the tombstone are divided into groups called brackets based

on their participation in the issue, and the names of the banks are listed alphabetically

within each bracket. The brackets are often viewed as a kind of pecking order. In general,

the higher the bracket, the greater is the underwriter’s prestige. In recent years, the use of

printed tombstones has declined, in part as a cost-saving measure. Crowdfunding

On April 5, 2012, the JOBS Act was signed into law. A provision of this act allowed companies

to raise money through crowdfunding, which is the practice of raising small amounts of

capital from a large number of people, typically via the Internet. Crowdfunding was first

used to underwrite the U.S. tour of British rock band Marillion, but the JOBS Act allows

companies to sell equity by crowdfunding. Specifically, the JOBS Act allows a company to

issue up to $1 million in securities in a 12-month period, and investors are permitted to invest

up to $100,000 in crowdfunding issues per 12 months. Although crowdfunding has been

passed into law, the SEC must still set the rules and regulations for these new “exchanges.”

20.3 Alternative Issue Methods

When a company decides to issue a new security, it can sell it as a public issue or a private

issue. If it is a public issue, the firm is required to register the issue with the SEC. If the

issue is sold to fewer than 35 investors, it can be treated as a private issue. A registration

statement is not required in this case.4

4However, regulation significantly restricts the resale of unregistered equity securities. For example, the purchaser may be

required to hold the securities for at least one year (or more). Many of the restrictions were significantly eased in 1990 for very

large institutional investors, however. The private placement of bonds is discussed in a later section.

CHAPTER 20 Raising Capital ■■■ 623 Figure 20.5

This announcement is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of an offer to buy any of these securities. An Example

The offering is made only by the Prospectus. of a Tombstone Advertisement New Issue 11,500,000 Shares

World Wrestling Federation Entertainment, Inc. Class A Common Stock Price $17.00 Per Share

Copies of the Prospectus may be obtained in any State in which this announcement

is circulated from only such of the Underwriters, including the undersigned,

as may lawfully offer these securities in such State. U.S. Offering 9,200,000 Shares

This portion of the underwriting is being offered in the United States and Canada.

Bear, Stearns & Co., Inc.

Credit Suisse First Boston

Merrill Lynch & Co.

Wit Capital Corporation

Al en & Company Banc of America Securities LLC Deutsche Banc Alex. Brown Incorporated

Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette A.G. Edwards & Sons, Inc. Hambrecht & Quist ING Barings

Prudential Securities SG Cowen Wassertein Perella Securities, Inc. Advest, Inc.

Axiom Capital Management, Inc. Blackford Securities Corp. J.C. Bradford & Co.

Joseph Charles & Assoc., Inc. Chatsworth Securities LLC Gabelli & Company, Inc.

Gaines, Berland, Inc. Jefferies & Company, Inc. Josephthal & Co., Inc. Neuberger Berman, LLC

Raymond James & Associates, Inc. Sanders Morris Mundy Tucker Anthony Cleary Gull Wachovia Securities, Inc. International Offering 2,300,000 Shares

This portion of the underwriting is being offered outside of the United States and Canada.

Bear, Stearns International Limited

Credit Suisse First Boston

Merrill Lynch International

624 ■■■ PART V Long-Term Financing

Table 20.1 The Methods of Issuing New Securities Method Type Definition Public Traditional Firm commitment

Company negotiates an agreement with an investment banker to negotiated cash offer

underwrite and distribute the new shares. A specified number of cash offer

shares are bought by underwriters and sold at a higher price. Best-efforts cash offer

Company has investment bankers sel as many of the new shares

as possible at the agreed-upon price. There is no guarantee con-

cerning how much cash wil be raised. Dutch auction cash

Company has investment bankers auction shares to determine the offer

highest offer price obtainable for a given number of shares to besold. Privileged Direct rights offer

Company offers the new stock directly to its existing subscription shareholders. Standby rights offer

Like the direct rights offer, this contains a privileged subscription

arrangement with existing shareholders. The net proceeds are

guaranteed by the underwriters. Nontraditional Shelf cash offer

Qualifying companies can authorize al the shares they expect to cash offer

sel over a two-year period and sel them when needed. Competitive firm

Company can elect to award the underwriting contract through a cash offer

public auction instead of negotiation. Private Direct placement

Securities are sold directly to the purchaser, who, at least until

recently, general y could not resel the securities for at least two years.

There are two kinds of public issues: the general cash offer and the rights offer. Cash

offers are sold to all interested investors, and rights offers are sold to existing shareholders.

Equity is sold by both the cash offer and the rights offer, though almost all debt is sold by cash offer.

A company’s first public equity issue is referred to as an initial public offering (IPO)

or an unseasoned equity offering. All initial public offerings are cash offers because,

if the firm’s existing shareholders wanted to buy the shares, the firm would not need to

sell them publicly. A seasoned equity offering (SEO) refers to a new issue where the

company’s securities have been previously issued. A seasoned equity offering of common

stock may be made by either a cash offer or a rights offer.

These methods of issuing new securities are shown in Table 20.1 and discussed in the next few sections. 20.4 The Cash Offer

As just mentioned, stock is sold to interested investors in a cash offer. If the cash offer

is a public one, investment banks are usually involved. Investment banks are financial

intermediaries that perform a wide variety of services. In addition to aiding in the sale

of securities, they may facilitate mergers and other corporate reorganizations and act as

brokers to both individual and institutional clients. You may well have heard of large Wall

Street investment banking houses such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

CHAPTER 20 Raising Capital ■■■ 625

For corporate issuers, investment bankers perform services such as the following:

Formulating the method used to issue the securities. Pricing the new securities. Selling the new securities.

There are three basic methods of issuing securities for cash:

1. Firm commitment: Under this method, the investment bank (or a group of invest-

ment banks) buys the securities for less than the offering price and accepts the risk

of not being able to sell them. Because this function involves risk, we say that the

investment banker underwrites the securities in a firm commitment. In other words,

when participating in a firm commitment offering, the investment banker acts as an

underwriter. (Because firm commitments are so prevalent, we will use investment

banker and underwriter interchangeably in this chapter.)

To minimize the risks here, a number of investment banks may form an underwrit- ing group (syndicat )

e to share the risk and to help sell the issue. In such a group, one

or more managers arrange or comanage the deal. The manager is designated as the lead

manager or principal manager, with responsibility for all aspects of the issue. The other

investment bankers in the syndicate serve primarily to sell the issue to their clients.

The difference between the underwriter’s buying price and the offering price

is called the gross spread or underwriting discount. It is the basic compensation

received by the underwriter. Sometimes the underwriter will get noncash compensa-

tion in the form of warrants or stock in addition to the spread.

Firm commitment underwriting is really just a purchase–sale arrangement, and

the syndicate’s fee is the spread. The issuer receives the full amount of the proceeds

less the spread, and all the risk is transferred to the underwriter. If the underwriter

cannot sell all of the issue at the agreed-upon offering price, it may need to lower

the price on the unsold shares. However, because the offering price usually is not set

until the underwriters have investigated how receptive the market is to the issue, this

risk is usually minimal. This is particularly true with seasoned new issues because

the price of the new issue can be based on prior trades in the security.

Since the offering price is usually set just before selling begins, the issuer

doesn’t know precisely what its net proceeds will be until that time. To determine

the offering price, the underwriter will meet with potential buyers, typically large

institutional buyers such as mutual funds. Often, the underwriter and company man-

agement will do presentations in multiple cities, pitching the stock in what is known

as a road show. Potential buyers provide information about the price they would be

willing to pay and the number of shares they would purchase at a particular price.

This process of soliciting information about buyers and the prices and quantities

they would demand is known as bookbuilding. As we will see, despite the book-

building process, underwriters frequently get the price wrong, or so it seems.

2. Best efforts: The underwriter bears risk with a firm commitment because it buys the

entire issue. Conversely, the syndicate avoids this risk under a best-efforts offering

because it does not purchase the shares. Instead, it merely acts as an agent, receiv-

ing a commission for each share sold. The syndicate is legally bound to use its

best efforts to sell the securities at the agreed-upon offering price. Beyond this, the

underwriter does not guarantee any particular amount of money to the issuer. This

form of underwriting has become relatively rare.

3. Dutch auction underwriting: With Dutch auction underwriting, the underwriter

does not set a fixed price for the shares to be sold. Instead, the underwriter conducts

626 ■■■ PART V Long-Term Financing

an auction in which investors bid for shares. The offer price is determined from the

submitted bids. A Dutch auction is also known by the more descriptive name uni-

form price auction. This approach is relatively new in the IPO market and has not

been widely used there, but is very common in the bond markets. For example, it is

the sole way that the U.S. Treasury sells its notes, bonds, and bills to the public.

To understand a Dutch or uniform price auction, consider a simple example.

Suppose the Rial Company wants to sell 400 shares to the public. The company receives five bids as follows: Bidder Quantity Price A 100 shares $16 B 100 shares 14 C 100 shares 12 D 200 shares 12 E 200 shares 10

Thus, bidder A is willing to buy 100 shares at $16 each, bidder B is willing to

buy 100 shares at $14, and so on. The Rial Company examines the bids to determine

the highest price that will result in all 400 shares being sold. For example, at $14, A

and B would buy only 200 shares, so that price is too high. Working our way down,

all 400 shares won’t be sold until we hit a price of $12, so $12 will be the offer

price in the IPO. Bidders A through D will receive shares, while bidder E will not.

There are two additional important points in our example. First, all the win-

ning bidders will pay $12—even bidders A and B, who actually bid a higher price.

The fact that all successful bidders pay the same price is the reason for the name

“uniform price auction.” The idea in such an auction is to encourage bidders to bid

aggressively by providing some protection against submitting a high bid.

Second, notice that at the $12 offer price, there are actually bids for 500 shares,

which exceeds the 400 shares Rial wants to sell. Thus, there has to be some sort of

allocation. How this is done varies a bit; but in the IPO market the approach has

been to simply compute the ratio of shares offered to shares bid at the offer price or

better, which, in our example, is 400/500 5 .8, and allocate bidders that percentage

of their bids. In other words, bidders A through D would each receive 80 percent of

the shares they bid at a price of $12 per share.

The period after a new issue is initially sold to the public is called the aftermarket.

During this period, the members of the underwriting syndicate generally do not sell shares

of the new issue for less than the offer price.

In most offerings, the principal underwriter is permitted to buy shares if the market price

falls below the offering price. The purpose is to suppor tthe market and stabiliz e the price

from temporary downward pressure. If the issue remains unsold after a time (e.g., 30 days),

members may leave the group and sell their shares at whatever price the market will allow.

Many underwriting contracts contain a Green Shoe provision, which gives the mem-

bers of the underwriting group the option to purchase additional shares at the offering

price.5 The stated reason for the Green Shoe option is to cover excess demand and over-

subscription. Green Shoe options usually last for about 30 days and involve 15 percent of

5The Green Shoe Corp. was the first firm to allow this provision.

CHAPTER 20 Raising Capital ■■■ 627

the newly issued shares. The Green Shoe option is a benefit to the underwriting syndicate

and a cost to the issuer. If the market price of the new issue goes above the offering price

within 30 days, the underwriters can buy shares from the issuer and immediately resell the shares to the public.

Almost all underwriting agreements contain lockups. Such arrangements specify how

long insiders must wait after an IPO before they can sell some of their stock. Typically,

lockup periods are set at 180 days. Thus, insiders must maintain a significant economic

interest in the company for six months following the IPO. Lockups are also important

because it is not unusual for the number of locked-up insider shares to exceed the number

of shares held by the public. Thus, when the lockup period ends, insiders may sell a large

number of shares, thereby depressing share price.

Beginning well before an offering and extending for 40 calendar days following an

IPO, the SEC requires that a firm and its managing underwriters observe a “quiet period.”

This means that all communication with the public must be limited to ordinary announce-

ments and other purely factual matters. The SEC’s logic is that all relevant information

should be contained in the prospectus. An important result of this requirement is that the

underwriters’ analysts are prohibited from making recommendations to investors. As soon

as the quiet period ends, however, the managing underwriters typically publish research

reports, usually accompanied by a favorable “buy” recommendation.

Firms that don’t stay quiet can have their IPOs delayed. For example, just before

Google’s IPO, an interview with cofounders Sergey Brin and Larry Page appeared in Playboy.

The interview almost caused a postponement of the IPO, but Google was able to amend its

prospectus in time. However, in May 2004, Salesforce.com’s IPO was delayed because an

interview with CEO Marc Benioff appeared in The New York Times. Salesforce.com finally went public two months later. INVESTMENT BANKS

Investment banks are at the heart of new security issues. They provide advice, market the

securities (after investigating the market’s receptiveness to the issue), and underwrite the

proceeds. They accept the risk that the market price may fall between the date the offering

price is set and the time the issue is sold.

An investment banker’s success depends on reputation. A good reputation can help

investment bankers retain customers and attract new ones. In other words, financial

economists argue that each investment bank has a reservoir of “reputation capital.” One

measure of this reputation capital is the pecking order among investment banks which,

as we mentioned earlier, even extends to the brackets of the tombstone ad in Figure 20.5.

MBA students are aware of this order because they know that accepting a job with

a top-tier firm is universally regarded as more prestigious than accepting a job with a lower-tier firm.

Investment banks put great importance in their relative rankings and view downward

movement in their placement with much distaste. This jockeying for position may seem

as unimportant as the currying of royal favor in the court of Louis XVI. However, in any

industry where reputation is so important, the firms in the industry must guard theirs with great vigilance.

A firm can offer its securities to the underwriter on either a competitive or a negotiated

basis. In a competitive offer, the issuing firm sells its securities to the underwriter with the

highest bid. In a negotiated offer, the issuing firm works with one underwriter. Because

the firm generally does not negotiate with many underwriters concurrently, negotiated

deals may suffer from lack of competition. In Their Own Words ROBERT S. HANSEN ON THE

bank’s future abounds. Capital market participants punish ECONOMIC RATIONALE FOR

poorly performing banks by refusing to hire them. The

THE FIRM COMMITMENT OFFER

participants pay banks for certification and meaningful

monitoring in “quasi-rents” in the spread, which represent

Underwriters provide four main functions: Certification,

the fair cost of “renting” the reputations.

monitoring, marketing, and risk bearing.

Marketing is finding long-term investors who can

Certification assures investors that the offer price

be persuaded to buy the securities at the offer price.

is fair. Investors have concerns about whether the

This would not be needed if demand for new shares

offer price is unfairly above the stock’s intrinsic value.

were “horizontal.” There is much evidence that issuers

Certification increases issuer value by reducing inves-

and syndicates repeatedly invest in costly marketing

tor doubt about fairness, making a better offer price

practices, such as expensive road shows, to identify and possible.

expand investor interest. Another is organizing members

Monitoring of issuing firm management and per-

to avoid redundant pursuit of the same customers. Lead

formance builds value because it adds to shareholders’

banks provide trading support in the issuer’s stock for

ordinary monitoring. Underwriters provide collective several weeks after the offer.

monitoring on behalf of both capital suppliers and current

Underwriting risk is like the risk of selling a put

shareholders. Individual shareholder monitoring is limited

option. The syndicate agrees to buy all new shares at the

because the shareholder bears the entire cost, whereas all

offer price and resell them at that price or at the market

owners collectively share the benefit, pro rata. By contrast,

price, whichever is lower. Thus, once the offer begins,

in underwriter monitoring all stockholders share both the

the syndicate is exposed to potential losses on unsold costs and benefits, pro rata.

inventory should the market price fall below the offer

Due diligence and legal liability for the proceeds give

price. The risk is likely to be small because offerings are

investors assurance. However, what makes certification

typically well prepared for quick sale.

and monitoring credible is lead bank reputation in com-

petitive capital markets, where they are disciplined over

Robert S. Hansen is the Francis Martin Chair in Business Finance and

time. Evidence that irreputable behavior is damaging to a

Economics at Tulane University.

Whereas competitive bidding occurs frequently in other areas of commerce, it may

surprise you that negotiated deals in investment banking occur with all but the largest

issuing firms. Investment bankers point out that they must expend much time and effort

learning about the issuer before setting an issue price and a fee schedule. Except in the

case of large issues, underwriters could not, it is argued, commit this time without the near

certainty of receiving the contract.

Studies generally show that issuing costs are higher in negotiated deals than

in competitive ones. However, many financial economists point out that the under-

writer gains a great deal of information about the issuing firm through negotiation—

information likely to increase the probability of a successful offering. THE OFFERING PRICE

Determining the correct offering price is the most difficult task the lead investment bank

faces in an initial public offering. The issuing firm faces a potential cost if the offering

price is set too high or too low. If the issue is priced too high, it may be unsuccessful and

have to be withdrawn. If the issue is priced below the true market price, the issuer’s exist-

ing shareholders will experience an opportunity loss. The process of determining the best

offer price is called bookbuilding. In bookbuilding, potential investors commit to buying

a certain number of shares at various prices. 628

CHAPTER 20 Raising Capital ■■■ 629 Table 20.2 Number of Average Number of Of erings, Year Offerings* First-Day Return, %† Average First-Day Return, and Gross 1960–1969 2,661 21.2% Proceeds of Initial 1970–1979 1,536 7.1 Public Of erings: 1980–1989 2,044 7.2 1960–2014 1990–1999 4,205 21.0 2000–2009 1,299 29.1 2010–2014 628 16.1 1960–2014 12,373 16.9%

*The number of offerings excludes IPOs with an offer price of less than $5.00, ADRs, best efforts, units, and Regulation A offers

(smal issues, raising less than $1.5 mil ion during the 1980s), real estate investment trusts (REITs), partnerships, and closed-end

funds. Banks and S&Ls and non-CRSP-listed IPOs are included.

†First-day returns are computed as the percentage return from the offering price to the first closing market price.

‡Gross proceeds data are from Securities Data Co., and they exclude overal otment options but include the international tranche,

if any. No adjustments for inflation have been made.

SOURCE: Professor Jay R. Ritter, University of Florida.

Underpricing is fairly common. For example, Ritter examined 12,373 firms that

went public between 1960 and 2014 in the United States. He found that the average IPO

rose in price 16.9 percent in the first day of trading following issuance (see Table 20.2).

These figures are not annualized!

Underpricing obviously helps new shareholders earn a higher return on the shares they

buy. However, the existing shareholders of the issuing firm are not helped by underpricing. To

them, it is an indirect cost of issuing new securities. For example, consider Chinese online

retailer Alibaba’s IPO in September 2014. The stock was priced at $68 in the IPO and rose

to a first-day high of $99.70, before closing at $93.89, a gain of about 38.1 percent. Based

on these numbers, Alibaba was underpriced by about $25.89 per share. Because Alibaba

sold 320.1 million shares, the company missed out on an additional $8.3 billion (5 $25.89 3

320.1 million), a record amount “left on the table.” The previous record of $5.1 billion was

held by Visa, set in its 2008 IPO.

UNDERPRICING: A POSSIBLE EXPLANATION

There are several possible explanations for underpricing, but so far there is no agreement

among scholars as to which explanation is correct. We now provide two well-known explana-

tions for underpricing. The first explanation begins with the observation that when the price of

a new issue is too low, the issue is often oversubscribe .

d This means investors will not be able

to buy all of the shares they want, and the underwriters will allocate the shares among investors.

The average investor will find it difficult to get shares in an oversubscribed offering because

there will not be enough shares to go around. Although initial public offerings have positive

initial returns on average, a significant fraction of them have price drops. Thus, an investor

submitting an order for all new issues may be allocated more shares in issues that go down in

price than in issues that go up in price.

Consider this tale of two investors. Ms. Smarts knows precisely what companies are

worth when their shares are offered. Mr. Average knows only that prices usually rise in the

first month after the IPO. Armed with this information, Mr. Average decides to buy 1,000

shares of every IPO. Does Mr. Average actually earn an abnormally high average return across all initial offerings? In Their Own Words

JAY RITTER ON IPO UNDERPRICING

in the United States, Germany, and other developed capital AROUND THE WORLD

markets has returned to more traditional levels.

The underpricing of Chinese IPOs used to be extreme,

The United States is not the only country in which initial

but in recent years it has moderated. In the 1990s Chinese

public offerings (IPOs) of common stock are under-

government regulations required that the offer price could

priced. The phenomenon exists in every country with a

not be more than 15 times earnings, even when compara-

stock market, although the extent of underpricing varies

ble stocks had a price–earnings ratio of 45. In 2011–2012, from country to country.

the average first-day return was 21%. But in 2013, there

In general, countries with developed capital markets

were no IPOs in China at all, due to a moratorium that the

have more moderate underpricing than in emerging markets.

government imposed because it thought that an increase in

During the Internet bubble of 1999–2000, however, under-

the supply of shares would depress stock prices.

pricing in the developed capital markets increased dramati-

The following table gives a summary of the average

cally. In the United States, for example, the average first-day

first-day returns on IPOs in a number of countries around

return during 1999–2000 was 65 percent. Since the bursting

the world, with the figures collected from a number of

of the Internet bubble in mid-2000, the level of underpricing studies by various authors. Avg. Avg. Sample Time Initial Sample Time Initial Country Size Period Return % Country Size Period Return % Argentina 26 1991–2013 4.2 Malaysia 474 1980–2013 56.2 Australia 1,562 1976–2011 21.8 Mauritius 40 1989–2005 15.2 Austria 10.3 1971–2013 6.4 Mexico 88 1987–1994 15.9 Belgium 114 1984–2006 13.5 Morocco 19 2004–2007 47.2 Brazil 275 1979–2011 33.1 Netherlands 181 1982–2006 10.2 Bulgaria 9 2004–2007 36.5 New Zealand 214 1979–2006 20.3 Canada 720 1971–2013 6.5 Nigeria 114 1989–2006 12.7 Chile 81 1982–2013 7.4 Norway 153 1984–2006 9.6 China 2,512 1990–2013 118.4 Pakistan 57 2000–2010 32.0 Cyprus 73 1997–2012 20.3 Philippines 123 1987–2006 21.2 Denmark 164 1984–2011 7.4 Poland 309 1991–2012 13.3 Egypt 62 1990–2010 10.4 Portugal 28 1992–2006 11.6 Finland 168 1971–2013 16.9 Russia 40 1999–2006 4.2 France 697 1983–2010 10.5 Saudi Arabia 76 2003–2010 264.5 Germany 736 1978–2011 24.2 Singapore 591 1973–2011 26.1 Greece 373 1976–2013 50.8 South Africa 285 1980–2007 18.0 Hong Kong 1,486 1980–2013 15.8 Spain 128 1986–2006 10.9 India 2,964 1990–2011 88.5 Sri Lanka 105 1987–2008 33.5 Indonesia 441 1990–2013 25.0 Sweden 374 1980–2011 27.2 Iran 279 1991–2004 22.4 Switzerland 159 1983–2008 28.0 Ireland 38 1991–2013 21.6 Taiwan 1,620 1980–2013 38.1 Israel 348 1990–2006 13.8 Thailand 459 1987–2007 36.6 Italy 312 1985–2013 15.2 Turkey 355 1990–2011 10.3 Japan 3,236 1970–2013 41.7 United Kingdom 4,932 1959–2012 16.0 Jordan 53 1999–2008 149.0 United States 12,373 1960–2014 16.9 Korea 1,720 1980–2013 59.3

Jay R. Ritter is Cordel Professor of Finance at the University of Florida. An outstanding scholar, he is wel known for his insightful analyses of new issues and going public.

SOURCE: Jay R. Ritter’s website.

CHAPTER 20 Raising Capital ■■■ 631

The answer is no, and at least one reason is Ms. Smarts. For example, because

Ms. Smarts knows that company XYZ is underpriced, she invests all her money in its IPO.

When the issue is oversubscribed, the underwriters must allocate the shares between

Ms. Smarts and Mr. Average. If they do this on a pro rata basis and if Ms. Smarts has

bid for, say, twice as many shares as Mr. Average, she will get two shares for each one

Mr. Average receives. The net result is that when an issue is underpriced, Mr. Average

cannot buy as much of it as he wants.

Ms. Smarts also knows that company ABC is overpriced. In this case, she avoids

its IPO altogether, and Mr. Average ends up with a full 1,000 shares. To summarize,

Mr. Average receives fewer shares when more knowledgeable investors swarm to buy an

underpriced issue, but he gets all he wants when the smart money avoids the issue.

This is called the winner’s curse, and it is one possible reason why IPOs have such a

large average return. When the average investor wins and gets his allocation, it is because

those who knew better avoided the issue. To counteract the winner’s curse and attract the

average investor, underwriters underprice issues.6

Perhaps a simpler explanation for underpricing is risk. Although IPOs on average have

positive initial returns, a significant fraction experience price drops. A price drop would

cause the underwriter a loss on his own holdings. In addition, the underwriter risks being

sued by angry customers for selling overpriced securities. Underpricing mitigates both problems.

20.5 The Announcement of New Equity and the Value of the Firm

As mentioned, when firms return to the equity markets for additional funds, they arrange

for a seasoned equity offering (SEO). The basic processes for an SEO and an IPO are

the same. However, something curious happens on the announcement day of an SEO.

It seems reasonable that long-term financing is used to fund positive net present value

projects. Consequently, when the announcement of external equity financing is made,

one might think that the firm’s stock price would go up. As we mentioned in an earlier

chapter, precisely the opposite actually happens. The firm’s stock price tends to decline

on the announcement of a new issue of common stock. Plausible reasons for this strange result include:

1. Managerial information: If managers have superior information about the market

value of the firm, they may know when the firm is overvalued. If they do, they

might attempt to issue new shares of stock when the market value exceeds the cor-

rect value. This will benefit existing shareholders. However, the potential new share-

holders are not stupid. They will infer overvaluation from the new issue, thereby

bidding down the stock price on the announcement date of the issue.

2. Debt capacity: We argued in an earlier chapter that a firm likely chooses its debt–

equity ratio by balancing the tax shield from the debt against the cost of financial

distress. When the managers of a firm have special information that the probability

of financial distress has risen, the firm is more likely to raise capital through stock

than through debt. If the market infers this chain of events, the stock price should

fall on the announcement date of an equity issue.

6This explanation was first suggested in Kevin Rock, “Why New Issues Are Underpriced,” Journal of Financial Economics 15 (1986).

632 ■■■ PART V Long-Term Financing

3. Issue costs: As we discuss in the next section, there are substantial costs associated with selling securities.

Whatever the reason, a drop in stock price following the announcement of a new issue

is an example of an indirect cost of selling securities. This drop might typically be on the

order of 3 percent for an industrial corporation (and somewhat smaller for a public utility);

so, for a large company, it can represent a substantial amount of money. We label this drop

the abnormal return in our discussion of the costs of new issues that follows.

To give a couple of recent examples, in April 2014, 3D printer company Voxeljet announced

a secondary offering. Its stock fell about 19.1 percent on the day of the announcement. Also in

April 2014, Hi-Crush Partners completed a secondary offering. Its stock dropped 7.4 percent

on the day of the announcement.

20.6 The Cost of New Issues

Issuing securities to the public is not free. The costs fall into six categories:

1. Gross spread, or underwriting discount:

The spread is the difference between the

price the issuer receives and the price offered to the public. 2. Other direct expenses:

These are costs incurred by the issuer

that are not part of the compensation to

underwriters. They include filing fees,

legal fees, and taxes—all reported in the prospectus. 3. Indirect expenses:

These costs are not reported in the pro-

spectus and include the time manage- ment spends on the new issue. 4. Abnormal returns:

In a seasoned issue of stock, the price

typically drops by about 3 percent upon

the announcement of the issue. The drop

protects new shareholders from buying overpriced stock. 5. Underpricing :

For initial public offerings, the stock typi-

cally rises substantially after the issue

date. This underpricing is a cost to the

firm because the stock is sold for less

than its efficient price in the aftermarket. 6. Green Shoe option:

The Green Shoe option gives the under-

writers the right to buy additional shares

at the offer price to cover overallot-

ments. This option is a cost to the firm

because the underwriter will buy addi-

tional shares only when the offer price is

below the price in the aftermarket.

Table 20.3 reports direct costs as a percentage of the gross amount raised for IPOs,

SEOs, straight (ordinary) bonds, and convertible bonds sold by U.S. companies over the

Table 20.3 Direct Costs as a Percentage of Gross Proceeds for Equity (IPOs and SEOs) and Straight and Convertible Bonds Offered by Domestic

Operating Companies: 1990–2008 IPOs SEOs Proceeds Number Gross Other Direct Total Number Gross Other Direct Total ($ millions) of Issues Spread Expense Direct Cost of Issues Spread Expense Direct Cost 2.00–9.99 1,007 9.40% 15.82% 25.22% 515 8.11% 26.99% 35.11% 10.00–19.99 810 7.39 7.30 14.69 726 6.11 7.76 13.86 20.00–39.99 1,422 6.96 7.06 14.03 1,393 5.44 4.10 9.54 40.00–59.99 880 6.89 2.87 9.77 1,129 5.03 8.93 13.96 60.00–79.99 522 6.79 2.16 8.94 841 4.88 1.98 6.85 80.00–99.99 327 6.71 1.84 8.55 536 4.67 2.05 6.72 100.00–199.99 702 6.39 1.57 7.96 1,372 4.34 .89 5.23 200.00–499.99 440 5.81 1.03 6.84 811 3.72 1.22 4.94 500.00 and up 155 5.01 .49 5.50 264 3.10 .27 3.37 Total/Avg 6,265 7.19 3.18 10.37 7,587 5.02 2.68 7.69 Straight Bonds Convertible Bonds CHAPTER 2.00–9.99 3,962 1.64% 2.40% 4.03% 14 6.39% 3.43% 9.82% 10.00–19.99 3,400 1.50 1.71 3.20 23 5.52 3.09 8.61 20.00–39.99 2,690 1.25 .92 2.17 30 4.63 1.67 6.30 20 40.00–59.99 3,345 .81 .79 1.59 35 3.49 1.04 4.54 R 60.00–79.99 891 1.65 .80 2.44 60 2.79 .62 3.41 aising 80.00–99.99 465 1.41 .57 1.98 16 2.30 .62 2.92 Ca 100.00–199.99 4,949 1.61 .52 2.14 82 2.66 .42 3.08 pital 200.00–499.99 3,305 1.38 .33 1.71 46 2.65 .33 2.99 500.00 and up 1,261 .61 .15 .76 7 2.16 .13 2.29 Total/Avg 24,268 1.38 .61 2.00 313 3.07 .85 3.92 ■ ■ ■

SOURCE: Inmoo Lee, Scott Lochhead, Jay Ritter, and Quanshiu Zhao, “The Costs of Raising Capital,” Journal of Financial Research 19 (Spring 1996), updated by the authors. 633

634 ■■■ PART V Long-Term Financing Table 20.4 Proceeds Number Gross Other Direct Total Direct and ($ millions) of Issues Spread Expense Direct Cost Underpricing Indirect Costs, in Percentages, 2.00–9.99 1,007 9.40% 15.82% 25.22% 20.42% of Equity IPOS: 10.00–19.99 810 7.39 7.30 14.69 10.33 1990–2008 20.00–39.99 1,422 6.96 7.06 14.03 17.03 40.00–59.99 880 6.89 2.87 9.77 28.26 60.00–79.99 522 6.79 2.16 8.94 28.36 80.00–99.99 327 6.71 1.84 8.55 32.92 100.00–199.99 702 6.39 1.57 7.96 21.55 200.00–499.99 440 5.81 1.03 6.84 6.19 500.00 and up 155 5.01 .49 5.50 6.64 Total/Avg 6,265 7.19 3.18 10.37 19.34

SOURCE: Inmoo Lee, Scott Lochhead, Jay Ritter, and Quanshiu Zhao, “The Costs of Raising Capital,” Journal of Financial Research

19 (Spring 1996), updated by the authors.

period from 1990 through 2008. Direct costs only include gross spread and other direct

expenses (Items 1 and 2 above).

The direct costs alone can be very large, particularly for smaller issues (less than $10

million). On a smaller IPO, for example, the total direct costs amount to 25.22 percent of

the amount raised. This means that if a company sells $10 million in stock, it can expect

to net only about $7.5 million; the other $2.5 million goes to cover the underwriter spread and other direct expenses.

Overall, four clear patterns emerge from Table 20.3. First, with the possible exception

of straight debt offerings (about which we will have more to say later), there are substantial

economies of scale. The underwriter spreads are smaller on larger issues, and the other direct

costs fall sharply as a percentage of the amount raised—a reflection of the mostly fixed

nature of such costs. Second, the costs associated with selling debt are substantially less than

the costs of selling equity. Third, IPOs have somewhat higher expenses than SEOs. Finally,

straight bonds are cheaper to float than convertible bonds.

As we have discussed, the underpricing of IPOs is an additional cost to the issuer. To

give a better idea of the total cost of going public, Table 20.4 combines the information

on total direct costs for IPOs in Table 20.3 with data on underpricing. Comparing the total

direct costs (in the fifth column) to the underpricing (in the sixth column), we see that,

across all size groups, the total direct costs amount to about 10 percent of the proceeds

raised, and the underpricing amounts to about 19 percent.

Recall from Chapter 8 that bonds carry different credit ratings. Higher-rated

bonds are said to be investment grade, whereas lower-rated bonds are noninvest-

ment grade. Table 20.5 contains a breakdown of direct costs for bond issues after

the investment and noninvestment grades have been separated. For the most part, the

costs are lower for investment grade. This is not surprising given the risk of nonin-

vestment grade issues. In addition, there are substantial economies of scale for both types of bonds.

THE COSTS OF GOING PUBLIC: A CASE STUDY

On April 10, 2014, Adamas Pharmaceuticals, the Emeryville, California-based pharma-

ceutical company, went public via an IPO. Adamas issued 3 million shares of stock at a

CHAPTER 20 Raising Capital ■■■ 635

price of $16 each. The lead underwriters on the IPO were Credit Suisse and Piper Jaffray,

assisted by a syndicate of other investment banks. Even though the IPO raised a gross

sum of $48 million, Adamas got to keep only $41.54 million after expenses. The biggest

expense was the 7 percent underwriter spread, which is ordinary for an offering of this

size. Adamas sold each of the 3 million shares to the underwriters for $14.88, and the

underwriters in turn sold the shares to the public for $16.00 each.

But wait—there’s more. Adamas spent $7,999 in SEC registration fees, $9,815 in other

filing fees, and $125,000 to be listed on the NASDAQ Global Market. The company also spent

$1.5 million in legal fees, $600,000 on accounting to obtain the necessary audits, $5,000 for

a transfer agent to physically transfer the shares and maintain a list of shareholders, $260,000

for printing and engraving expenses, and finally, $592,816 in miscellaneous expenses.

As Adamas’ outlays show, an IPO can be a costly undertaking! In the end, Adamas’

expenses totaled $6.46 million, of which $3.36 million went to the underwriters and

$3.1 million went to other parties. All told, the total cost to Adamas was 15.6 percent of

the issue proceeds raised by the company. 20.7 Rights

When new shares of common stock are offered to the general public in a seasoned equity

offering, the proportionate ownership of existing shareholders is likely to be reduced.

However, if a preemptive right is contained in the firm’s articles of incorporation, the firm

must first offer any new issue of common stock to existing shareholders. This assures that

each owner can keep his proportionate share.

An issue of common stock to existing stockholders is called a rights offering. Here

each shareholder is issued an option to buy a specified number of new shares from the

firm at a specified price within a specified time, after which the rights expire. For example,

a firm whose stock is selling at $30 may let current stockholders buy a fixed number of

shares at $10 per share within two months. The terms of the option are evidenced by

certificates known as share warrants or rights. Such rights are often traded on securities

exchanges or over the counter. Rights offerings are very common in Europe but not in the United States.

THE MECHANICS OF A RIGHTS OFFERING

We illustrate the mechanics of a rights offering by considering National Power Company.

National Power has 1 million shares outstanding and the stock is selling at $20 per share,

implying a market capitalization of $20 million. The company plans to raise $5 million of

new equity funds by a rights offering.

The process of issuing rights differs from the process of issuing shares of stock for

cash. Existing stockholders are notified that they have been given one right for each share

of stock they own. Exercise occurs when a shareholder sends payment to the firm’s sub-

scription agent (usually a bank) and turns in the required number of rights. Shareholders

of National Power will have several choices: (1) subscribe for the full number of entitled

shares, (2) sell the rights, or (3) do nothing and let the rights expire. SUBSCRIPTION PRICE

National Power must first determine the subscription price, which is the price that

existing shareholders are allowed to pay for a share of stock. A rational shareholder will