Preview text:

519458 COS0010.1177/0020715213519458International Journal of Comparative SociologyRoberts research-article2014 article

Peripheral accumulation in the International Journal of

world economy: A cross-national Comparative Sociology 2014, Vol. 54(5-6) 420–444 © The Author(s) 2014

analysis of the informal economy Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0020715213519458 cos.sagepub.com Anthony Roberts

University of California, Riverside, USA Abstract

The persistence and growth of the informal economy have puzzled researchers and challenging mainstream

explanations of the development of the informal economy. This study utilizes a world-systems approach for

explaining cross-national variation in the size of the informal economy for a sample of 74 developing and

developed countries observed over a recent 8-year period (1999–2007). According to this approach, the

informal economy is a characteristic of peripheral accumulation in the world economy and its development

is driven by unequal exchange in international trade and foreign capital penetration. Based on estimates

from random and fixed-effects regression models using multiple measures of world-system position,

countries in the periphery and semi-periphery of the world economy have larger informal economies than

core countries. More importantly, this difference in the development of the informal economy between the

core, semi-periphery, and periphery is partially explained by the effects of international trade and foreign

direct investment. Overall, the findings indicate that the development and persistence of the informal

economy are driven by the structure of the world economy and processes of economic globalization. Keywords

Economic development, economic globalization, government regulation, informal economy, world-systems Introduction

The informal economy, or the aggregation of unrecorded and unregulated economic activities,

remains an important element of contemporary capitalism. Over the last 40 years, an extensive lit

erature emerged across several academic fields as researchers attempt to document and explain

the development of the informal economy in developed and less-developed countries. Given the

prolif eration of research on the informal economy, it is unsurprising that disagreeableness over

the nature and determinants of the informal economy remains. However, the scarcity of

internationally comparable data on the size of the informal economy limits the ability to adjudicate

competing arguments in the literature. This difficulty in conceptualizing and measuring the informal economy is Corresponding author:

Anthony Roberts, Sociology Department, University of California, Riverside, 1206 Watkins Hal , Riverside, CA 92521, USA.

Email: anthony.roberts@email.ucr.edu

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 421

attributable to the clandestine nature of informal economic activity (Feige, 1990; Portes and Hal er, 2005;

Schneider et al., 2010). Recently, address this issue by treating the informal researchers econ omy as an

unobservable component of national economies which is measurable through a set of observable indicators.

Utilizing this 'latent variable approach', these researchers develop international y comparable estimates of

the size of the informal economy (Giles, 1999; Schneider, 2005; Schneider et al., 2010).1 The recent

availability of international y comparable data on the size of the informal economy al ows for a systematic

assessment of competing views on the nature and determinants of the informal economy using a macro- comparative approach.

A number of country-specific case studies document the roles of a wide range of social, politi cal, and

economic factors in promoting the development of informal economy (Borocz, 2000; Bosch and Maloney,

2010; Davies and Thurlow, 2010; De Soto , 1989; Hart, 1973; Kaya, 2008; Kesteloot and Meert, 1999;

Wil iams and Round, 2008). While these case studies provide valuable information on the informal economy,

the generalizability of this information is extremely limited.

Previous scientific studies study cross-national variation in the size of the informal economy, but rely on

proxies of the informal economy, such as the size of the service labor force (Evans and Timberlake) or self-

employment (Ihrig and Moe, 2001; Loayza and Rigolini, 2011). Based on this limitation in the literature,

recent studies use direct and international y comparable estimates of the size of the informal economy to

explain cross-national variation (Djankov and Ramalho, 2009; Ihrig and Moe, 2004; Kus, 2010). This article

continues this approach by examining variation in the size of the informal economy across a large cross

section of countries from 1999 to 2007 using recently available national estimates of the size of the informal

economy (see Schneider et al., 2010).

Original y, the informal economy was associated with the subsistence activities of the marginalized

urban poor or the pre-capitalist economic activities of rural populations (Hart, 1973; International Labor

Organization (ILO), 1972; Sethuraman, 1976; Tokman, 1978). Yet, the persistence and growth of the

informal economy in highly developed countries (Castel s and Portes, 1989; Organization for Economic Co-

operation and Development (OECD), 2009; Portes and Sassen Koob, 1987; Sassen, 1997, 2001; Schneider

and Enste, 2002; Tanzi, 1980, 1983) and industrializing less-developed countries (Borocz, 2000; Davis,

2006; De Soto, 1989; Ihrig and Moe, 2001; ILO, 2002; Maloney, 2004; Schneider, 2005; Schneider et al. al.,

2010) raised over this nascent view of the informal economy. The empirical shortcomings of this early

generated several new theories of informalization, which processes of economic globalization, globalization,

and economic perspective development as the main causes of informality. However, recent theorization

omits the general argument that the informal economy is a necessary component of capitalist accu mulation

in the world economy (Portes, 1978; Portes and Walton, 1981). In this article, I address this omission by

investigating the relationship between the informal economy and the world economy.

In the current literature, researchers recognize that the informal economy is composed of a highly

heterogeneous set of income-generating activities and past theorization is sufficient for adequately

conceptualizing its diverse nature (Wil iams and Round, 2008). Based on this criticism, it is important to

investigate how informal activities are directly or indirectly linked to the production of goods and services in

the formal economy (Castel s and Portes, 1989; Portes and Sassen Koob 1987; Portes and Walton, 1981).

From this alternative perspective, the informal economy is defined as the aggregation of income-generating

processes which are unregulated by the national laws and regulations and embedded in the production

processes of formal goods and services (Castel s and Portes, 1989; Portes and Hal er, 2005 ). Instead of

conceiving of the informal economy as a social safety net for the marginalized poor or simply the economic

activities of rural populations, this perspective emphasizes the interdependence between formal and informal eco nomic activities.

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google

422 International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54(5-6)

Theories of informal economy are grounded in three general perspectives: (1) the dualist per

spective, (2) the legalist perspective, and (3) the structural perspective (Chen, 2009). The dualist

perspective conceives of the informal economy as a separate sector of economic activity which is

preeminent driven by macroeconomic conditions and economic development. According to this view,

during periods of economic growth and strong labor market performance, the informal sector contracts

as informal producers and workers migrate to the formal sector (Hart, 1973; ILO, 1972).

The legalist perspective views the informal economy as an unregulated sector composed of smal scale

entrepreneurs trying to avoid the economic burden of overt regulation (De Soto, 1989; Kus, 2010;

Maloney, 2004). Based on this argument, conditions of overt economic regulation and lax enforcement

incentivize informal petty production, which causes the informal economy to expand.

These conceptualizations of the informal economy are inaccurate because they assume that infor mal

economic activity is independent of the formal economy. The structural perspective empha sizes how

formal and informal economic activities are utilized in the production of formal goods and services as

way to subsidize the cost of labor-intensive production (Castel s and Portes, 1989; Moser, 1978; Portes

and Walton, 1981; Tabak and Crichlow, 2000).

Structural theories of the informal economy view the informal economy as a persistent feature of

capitalist accumulation in the world economy. specifical y, the informal economy is viewed as a critical

component of capitalist accumulation in countries occupying peripheral and semi-peripheral roles in

world economy (Evans and Timberlake, 1980; Portes, 1978; Portes and Walton, 1981).

According to world-systems perspective, countries occupy stratified roles in the world economy which

corresponds to an unequal international division of labor (IDL) (see Babones, 2005; Chase Dunn, 1989;

Lloyd et al., 2009 for a review). Countries located in the periphery and semi-periphery of the world

economy tend to specialize in labor-intensive and competitive industries, while coun tries located in the

core specialize in capital- and skil -intensive production in monopolized indus tries (Arrighi and Dragonal,

1986 ; Chase-Dunn, 1989; Evans, 1979; Wal erstein, 1974a). In turn, this unequal IDL is reproduced

through exploitive economic relations between the core and periphery where economic value is re-

appropriated from the periphery and semi-periphery to the core through processes of trade and investment.

This article's main contention is that the informal economy is an essential structural component of

peripheral accumulation – profit-making in competitive and labor-intensive industries through minimizing

labor costs (Portes, 1978: 37; Portes and Walton, 1981: 84). Since local firms in the periphery and semi-

periphery specialize in labor-intensive production, profits are tied directly to the cost of labor. These firms

are reliant on the informal economy to suppress formal wages, to supply low-wage informal workers, and

to reproduce low-wage workers with inexpensive goods and services (Bienefeld, 1975; Portes, 1978;

Portes and Sassen-Koob, 1987; Portes and Walton, 1981). Yet, even though this argument originated in

the late 1970s and early 1980s, few empirical studies investigate the relationship between the IDL and

the informal economy. This is surprising given Alejandro Portes (1978) criticism that '… the informal

economy represents a fundamental concept for understanding the operation of capitalism as a world

phenomenon and constitutes a missing element in contemporary world-system formulations of core and

periphery' (p. 35 ). The main purpose of this article is to address Portes' critique by empirical y analyzing

how the structure of the world economy affects the size of the informal economy in 74 developed and

less-developed countries observed over a recent 8-year period (1999–2007) .

The persistence and growth of the informal economy

The persistence and growth of the informal economy in developed and less-developed countries during

periods of economic growth and deregulation chal enge the dualist and legalist perspectives

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 423

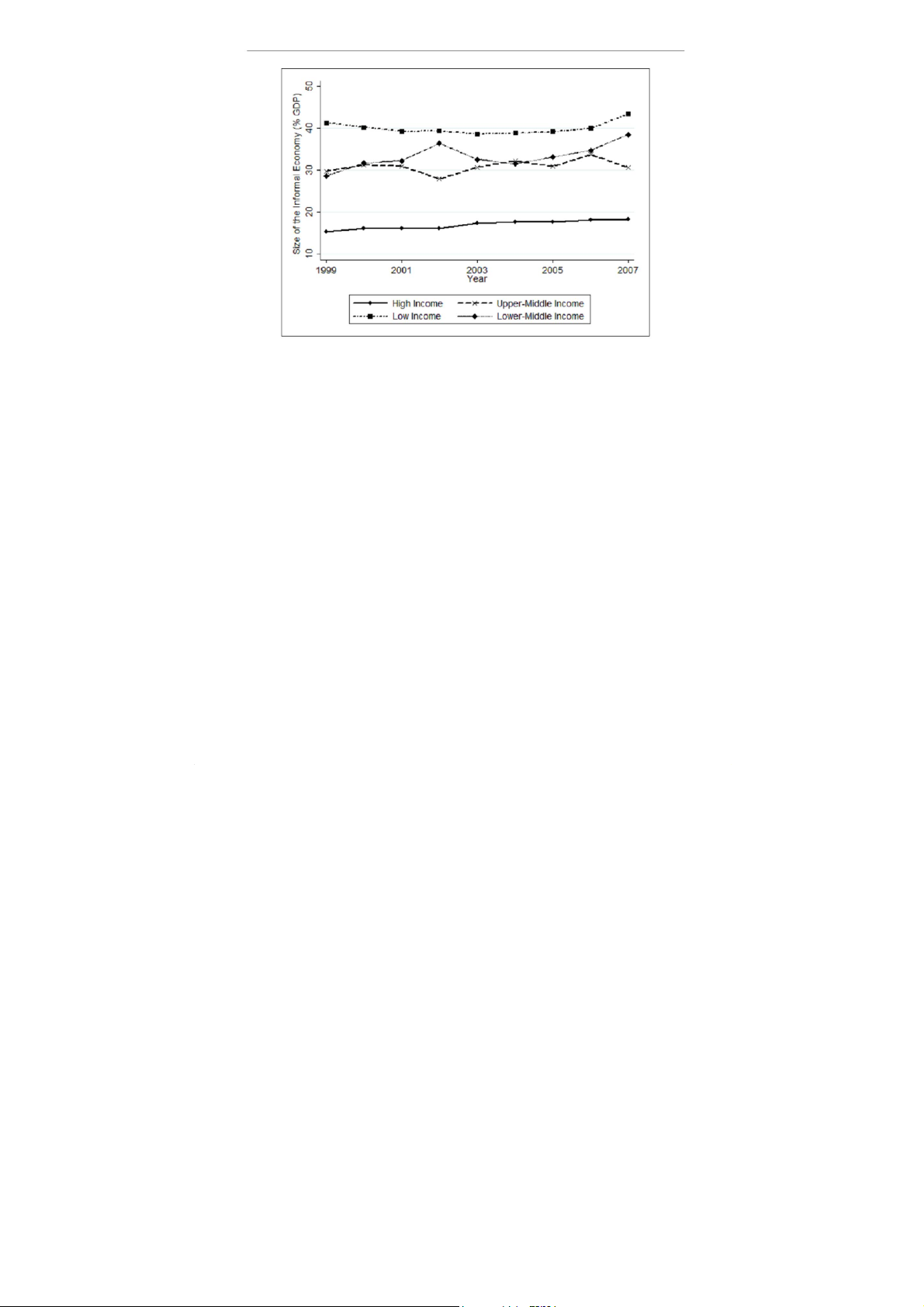

Figure 1. Trends in informal economic development by income group, 1999–2007.

Source: Schneider et al. (2010). GDP: gross domestic product.

on the informal economy. For example, from 1975 to 2000, less-developed regions (North Africa, Sub-

Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia) experienced an average growth of 2.5–3.5 percent in

gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, while the informal share of non-agricultural employment increased

by about 10 percent (OECD, 2009: Figure 3.3). This trend is not unique to less-developed regions. Over the

same period, in the United States and Western Europe, the infor mal economy grew from 5.3 percent of

official GDP to 16.5 percent of official GDP (Schneider and Enste, 2002), while the informal share of the non-

agricultural labor force grew from 10 percent to 15 percent (OECD, 2009: Figure 2.3). The important

questions are whether the informal economy continued to grow since 2000 and whether cross-national

differences in the size of the informal economy remain.

Figure 1 shows the average size of the informal economy, based on estimates from Schneider et al.

(2010), across high-, upper-middle-, low-middle-, and low-income countries, as defined by the World Bank's

2010 Income Group classification scheme. Indeed, as seen in Figure 1, while the informal economy grew in

developed and less-developed countries from 1999 to 2007, the size of the informal economy varied by level

of development. In high-income countries, where gross national product (GNP) per capita exceeds

US$12,500, the informal economy expanded by 26 percent, growing from 15 percent of official GDP to 19

percent of official GDP, even though official GDP grew by over 2 percent over this period. Similarly, in low-

income countries, where GNP per capita is less than US$1000, the informal economy expanded by 36

percent, growing from 28 percent of official GDP to 38 percent while the official GDP grew by 3 percent over

this period (World Bank , 2012).

This ubiquitous growth of the informal economy across al income groups chal enges the genetic claims

of the early dualist and legalist perspectives. According to the dualist perspective,

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google 424

International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54(5-6)

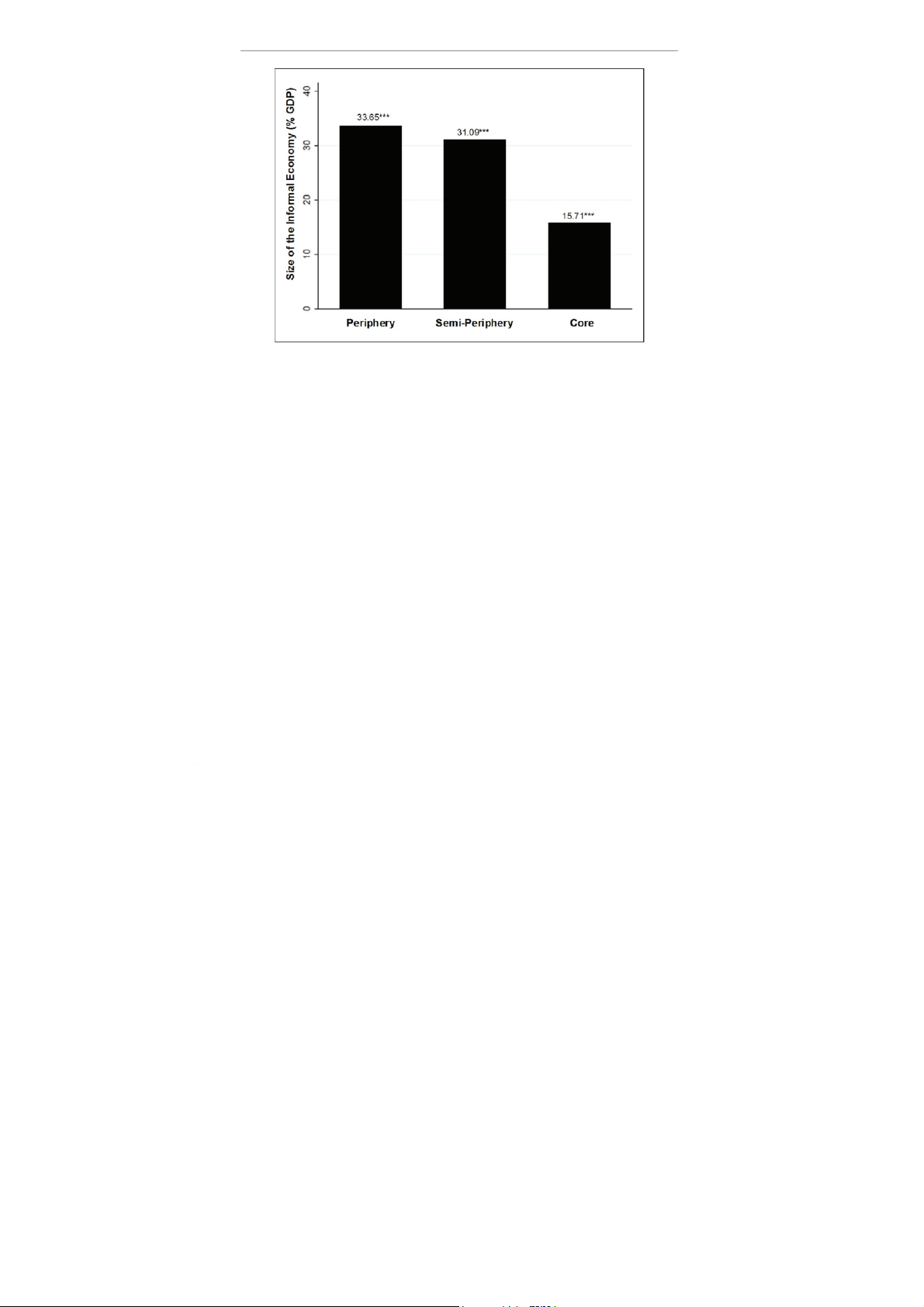

Figure 2. Average size of the informal economy by world-system position.

Source: World-system position – Snyder and Kick (1979) as updated in Bollen and Appold (1993); size of the informal

economy – Schneider et al. (2010). GDP: gross domestic product.

***p < .001 for mean difference t-tests comparing group means.

Economic growth should reduce the size of the informal economy as higher labor demand and

entrepreneurial opportunities in the formal sector attract workers and petty producers from the informal

sector (Tokman, 1978). However, over the last few decades the informal economy grew in low-, middle-,

and high-income countries even though these countries experienced growth in the formal economy.

According to the legalist perspective, the recent expansion and persistence of the informal economy are

attributed to the enactment of new economic regulations (Djankov and Ramalho, 2009), but the growth

of the informal economy during a period of rapid deregulation in developed countries raises concerns

over the validity of this argument (Heintz and Pol in, 2003).

Economic development, regulation, and the informal economy

A revision to the dualist perspective emerging in the literature to address the empirical implications of

that perspective on the relationship between the informal economy and economic development.

While this revised dualist perspective retains the basic view on the relative autonomy of the infor mal

economy, it advances the original dualist position by identifying how processes of internal economic

development (eg urbanization, industrialization, and unemployment) affecting the devel opment of the

informal economy . However, the failure to associate these internal processes with world economy

continues to limit this revised perspective.

Starting with the observed subsistence activities of the urban poor in Ghana (Hart, 1973) and

Kenya (ILO, 1972), researchers associate the expansion of the informal economy with the rapid

urbanization of less-developed countries (Gugler, 1982; Koo and Smith, 1983; McGee, 1973;

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 425

Moser, 1978; Sethuraman, 1976). These observations are fairly consistent with the early 'over urbanization

hypothesis', which argues that growth of the informal economy in less-developed countries is caused by the

rapid in-migration of rural populations into industrializing urban centers (Gibbs and Martin, 1962; Smith ,

1987). In more recent studies, researchers argue that international migration into urban centers induces a

growth in the informal economy because international migrants are unable to find employment and business

opportunities in the formal economy due to legal and cultural barriers (Chiang, 2004; Raijman and Tienda,

2000; Waldinger and Lapp, 1993).

According to the 'urbanization hypothesis', the informal economy expands as both international and rural

migrants are incorporated into the urban economy as informal petty producers and/or informal labor because

of barriers to entry in the formal sector.

An explicit and central argument of the dualist perspective is the distinction between enter businesses

in the formal and informal sectors. The formal sector is composed of large-scale industrial firms employing

unskil ed and semi-skil ed manufacturing workers, while the informal sector is made up of smal -scale petty

producers, street vendors, and home-based workers (Chen, 2009; Gerry, 1987 ; Kus, 2010). structuring,

rapid growth in the formal industrial sector causes a decline in the informal sector as large-scale industrial

firms increase their demand for manufacturing labor. This argument is based on the assumption that the

informal sector operates as an autonomous arena for income-generating activity during periods of economic

downturn. In particular, during slow growth periods, industrial firms in the formal sector reduce their demand

for labor as they attempt to lower production costs. Thus, as opportunities for employment in the industrial

sector decline, the size of the informal economy is expected to grow. Therefore, in accordance with the

'industrialization hypothesis', the size of the informal economy decreases with the growth of the

manufacturing sector because industrial expansion induces a labor force shift from the informal to the formal industrial sector.

Recent evidence suggests that the unemployment rate is positively associated with the size of the

informal sector because a reduction in the effective demand for labor in the formal sector causes workers to

migrate into the informal sector (Bajada and Schneider, 2009; Bosch and Maloney, 2008 , 2010; Henry,

1987). However, some researchers suggest that the rate is negative related to the size of the informal

economy. For example, the unemployment rate in South Africa exceeded 40 percent in 2002, but the size

of the informal workforce remained relatively smal compared to previous periods (Kingdon and Knight,

2004). This observation is primarily attributed to the availability of private credit to household and wage

inflation, which limits labor migration from the formal sector to the informal sector (Davies and Thurlow,

2010). The inconclusive relationship between the formal unemployment rate and the size of the informal

econo omy warrants more in-depth investigation.

In the late 1980s a new theory of the informal economy emerged in the literature which contrived rational

participation in the informal economy and based on the decision making of petty entrepreneurs and workers.

Specifical y, this perspective argues that firms, entrepreneurs, and workers decide to operate informal y to

avoid the additional costs created by excessive regulations and taxation (Chen, 2009). These researchers

posit that the size of the infor mal economy depends on the intensity of economic regulations (De Soto,

1989; Ihrig and Moe, 2001, 2004; Loayza and Rigolini, 2011; Macias and Cazzavil an, 2009; Maloney, 2004;

Ulyssea, 2010) and the quality of regulatory enforcement (Kus, 2010).

In Hernando De Soto's (1989) The Other Path, the informal economy in Peru is seen as a response to

the expansion of the state regulations. De Soto argues that the decision of rural migrants to operate as

informal vendors is mainly attributed to the extensive regulatory requirements for acquiring a business

license and operating a formal business in Peru. Based on this important case study, researchers began to

analyze the effects of business flexibility on the informal economy in

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google 426

International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54(5-6)

Mexico (Macias and Cazzavil an, 2009), Brazil (Ulyssea, 2010), and in a sample of 54 developed and

less-developed countries (Loayza and Rigolini, 2011). These studies find that business flexibility reduces

the size of the informal economy and the informal labor force by minimizing the costs associated with

operating a business and employing workers in the formal economy. Thus, according to the 'regulatory

burden hypothesis', an increase in business flexibility is associated with a decrease in the size of the

informal economy as the costs of entering and operating in the formal economy decrease.

While most of the literature focuses on the degree of economic regulations, a recent study cal s

attention to the quality of enforcement – the degree to which countries effectively and consistently

enforce economic regulations (Kus, 2010: 494). Drawing on insights from Max Weber, this study argues

that economic actors are more likely to engage in informal economic activity when there is a low likelihood

of being sanctioned by state actors (see also Portes and Centeno, 2006; Portes and Hal er, 2005). The

study finds that the quality of enforcement is a greater determinant of the size of the informal economy

than the intensity of economic regulations based on a cross-sectional analysis of 78 countries. The

'regulatory enforcement hypothesis' states that the size of the informal economy is inversely related to

the quality of enforcement because economic actors are more likely to operate informal y when economic

regulations are inappropriately enforced.

Overal , the dualist and legalist perspectives received extensive theoretical and empirical attention in

the recent literature on the informal economy, while structural perspectives are largely ignored. This is

troubling given the persistent and valid argument that developmental processes and economic regulations

are products of a country's structural position in the world economy (Chase-Dunn, 1989; Evans, 1979,

1995). More importantly, despite recent research on the effect of international trade and investment on

the recent expansion of the informal economy (Carr and Chen, 2002; Heintz and Pol in, 2003; Phil ips,

2011; Standing, 1999), most studies testing the legalist and dualist perspectives fail to sufficiently

account for the effects of international trade and investment on the informal economy. In response to

these theoretical and empirical gaps in the literature on the informal economy, I analyze how a country's

structural position in the world economy, international trade, and foreign direct investment (FDI) affects

the development of the informal economy.

The structure of the world economy and the informal economy

The main purpose of the article is to investigate the relationship between the structure of the world

economy and the size of the informal economy. specifical y, I test whether countries located in the

periphery and semi-periphery of the world economy exhibit larger informal economies than coun tries

located in the core. This analysis is based on the argument that a large informal economy is a vital

condition of peripheral capitalism because it subsidizes formal firms engaged in labor intensive

production (Portes and Walton, 1981: 84–88).

A central insight of the world-systems perspective is that the world economy is hierarchical y organized

around three structural roles: the core, the semi-periphery, and the periphery (Wal erstein, 1974b: 401).2

This tripartite organization induces countries to develop differentiation regimes of capitalist accumulation

according to their role in the world economy (Chase-Dunn and Rubinson, 1977: 456–457; Evans, 1979).

Core countries tend to specialize in capital- and skil -intensive production of high-value commodities in

monopolized industries which requires investment in human and productive capital for profit accumulation.

Peripheral countries specialize in labor-intensive production of low-value commodities in highly

competitive industries that require a large work force of unskil ed and low-wage labor for profit

accumulation (Arrighi and Drangel 1986; Chase Dunn, 1989; Mahutga, 2006; Mahutga and Smith,

2011). Semi-peripheral countries perform a

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 427

structural y important role in stabilizing the world economy by specializing in a mix of skil intensive and

labor-intensive production processes and serving as an intermediary between the core and periphery (Arrighi

and Dragonel, 1986: 12; Chase-Dunn and Rubinson, 1977; Evans , 1979; Wal erstein, 1974c). As a

consequence of this international division, core countries developed highly sophisticated governance and

diversified governance with strong institutions, while periph ery countries tend to develop simple economies

and weak institutions (Chase-Dunn, 1989; Chase-Dunn and Rubinson, 1977). Overal , the structure of the

world economy is important for explaining cross-national variation in social, economic, and political development.

Indeed, over the last 30 years an extensive empirical literature validates the general claim that the

structural position of a country in the world economy directly affects national inequality (Alderson and

Nielsen, 1999; Lee et al., 2007; Mahutga et al., 2011 ; Nolan, 1983), economic development (Clark, 2010;

Mahutga and Smith, 2011; Nolan, 1983), industrialization (Bol en and Appold, 1993), and democratic

governance (Bol en, 1983; Clark, 2012). However, to date, no study tests whether the structure of the world

economy accounts for cross-national variation in the size of the informal economy. The lack of empirical

evidence on the relationship between the structure of the world economy and the informal economy is

problematic, given the persistent argument in the world-systems literature that the informal economy is a

component of peripheral accumulation (Chase-Dunn, 1989 : 235; Portes, 1978; Portes and Walton, 1981; Smith, 1987).

Figure 2 reports the average size of the informal economy in the core, semi-periphery, and periphery

based on international y comparable estimates from Schneider et al. (2010). Figure 2 shows a significant

difference in the average size of the informal economy between core, semi peripheral, and peripheral

countries. In the periphery, the average size of the informal economy is about 34 percent of the size of the

official economy, while in the semi-periphery, the average size of the informal economy is about 31 percent

of the size of the official economy. Compared to the core, the size of the informal economy in peripheral and

semi-peripheral countries is twice as large. This difference in size provides tentative support for the general

claim that informal eco nomic activity is far more prevalent in the periphery and semi-periphery. The next

step is to identify the world economic processes that produce this difference in the size of the informal economy across the IDL.

Unequal exchange, disarticulation, and the informal economy

Over the last decade, an emerging literature argues that economic globalization is the primary force causing

the persistence and recent expansion of the informal economy in developed and less-devel oped countries

(Carr and Chen, 2002; Heintz and Pol in, 2003; Phil ips, 2011 ; Standing, 1999).

According to this new perspective, the rapid intensification of global trade induces local firms to utilize

informal labor and products as a means of reducing production costs to maintain competitiveness in an

increasingly global economy. The main problem with this argument is the assumption that economic

globalization has the same effect on the informal economy in the core, periphery, and semi-periphery.

Drawing on insights from the world-system perspective, I argue that the effects of economic globali zation

are conditioned by a country's location in the structure of the world economy (Bornschier and Chase-Dunn,

1985; Wal erstein, 1974b). I contend that both international trade and investment have a stronger effect on

the size of informal economy in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries.

According to the world-systems perspective, processes of trade and investment are the primary

mechanisms reproducing the IDL by transferring value from the periphery and semi-periphery to the core

and hindering growth in the non-core (Bornschier and Chase-Dunn, 1985; Wal erstein, 1974b). Trade in the

world economy is characterized as an unequal exchange between core and non-core countries because

core states mainly export high-tech manufacturing goods or

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google

428 International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54(5-6)

high-value services, while periphery and semi-periphery state primarily labor export-intensive light

manufacturing goods and raw materials (see Arrighi and Drangel, 1986; De Santos, 1970; Mahutga and

Smith, 2011; Wal erstein, 1974a). The difference in the relative value of traded com modities re-

appropriates surplus value from the non-core to the core, which reproduces the non core's subordinate

status in the IDL. In addition, investment in the world economy reproduces the IDL by suppressing the

development of non-core economies through creating a condition of secto ral disarticulation, where

economic growth is concentrated in foreign-dominated sectors. Since the periphery and semi-periphery

specialize in low-value and labor-intensive industries, they are dependent on the transfer of capital and

technology from the core (Caporaso, 1981; De Janvry and Garramon, 1977). Dependence on foreign

capital causes local sectors to stagnate when economic development is induced by FDI because the

local economy is unable to supply the requisite inputs for production in foreign-dominated sectors.

Commodity trade between the core and the non-core re-appropriates value to the core through

exploiting international differences in production capacity and commodity value (Arrighi and Dragonal,

1986; Emmanuel, 1972; Wal erstein, 1974a: 401). The returns from international trade for periphery and

semi-periphery countries are minimal because these countries specialize in the production of low-value

goods and the extraction of raw materials. The low rate of returns from inter national trade forces local

firms to utilize the informal economy to subsidize the formal production of labor-intensive and low-value

goods and services. Therefore, according to the 'unequal exchange hypothesis', international trade

should increase the size of the informal economy in the semi periphery and periphery, while having no

effect on the size of the informal economy in the core.

The inflow of foreign capital into the periphery and semi-periphery creates a condition of sectoral

disarticulation, where export-oriented sectors dominated by foreign capital experience rapid growth while

becoming 'disarticulated' from the local economy (Amin, 1974; Beer and Boswel , 2002; Bornschier and

Chase-Dunn, 1985; Dixon and Boswel , 1996; Stokes and Anderson, 1990).

In peripheral and semi-peripheral countries, foreign capital has a tendency to concentrate into a few

industrialized and export-oriented sectors, increasing the capital intensity of production in these sectors

vis-a-vis local sectors (Amin, 1974; Evans and Timberlake , 1980; Mahutga and Bandelj, 2008).

Gains from the development of the export-oriented sector are unable to spread to other sectors because

the local economy is unable to provide the requisite capital inputs and skil ed labor to the foreign-

dominated sector. In addition, the profits generated in export-oriented sectors are captured by foreign

investors and firms, which reduce the capacity for local investment (Bornschier and Chase-Dunn, 1985).

The main consequence of this developmental pattern is the increasing reli ance on the informal economy

to subsidize labor-intensive production in local sectors.

Additional y, the capital intensity of production in foreign-dominated sectors reduces the demand for

unskil ed labor in these sectors (Feenstra and Hanson, 1997). For example, Evans and Timberlake

(1980) argue that foreign capital dependence induces growth in service sector employment in less-

developed countries because foreign-dominated industrial sectors are unable to absorb a large portion

of the local unskil ed labor force. This decrease in the demand for unskil ed labor reduces the wages of

unskil ed workers and increases the demand for inexpensive goods and ser vices from the informal

economy. According to the 'disarticulation hypothesis', an increase in FDI is expected to increase the

size of the informal economy in periphery and semi-periphery countries, while having no effect in the core countries. Data and methods

In this article, I analyze the direct and conditional effects of the structure of the world economy on the

size of the informal economy using unbalanced panel data for 74 developed and less-developed

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 429

countries from 1999 to 2007.3 Data are restricted to 74 countries because of missing data and the exclusion

of countries with less than three observations during the observed period. The sample includes 24 high-

income, 16 upper-middle-income, 20 lower-middle-income, and 14 low-income countries. Overal , the sample

contains 554 country-year observations.

Dependent variable: size of the informal economy

Data on the size of the informal economy are drawn from a recent study which utilized confirma tory factor

analysis (CFA) to derive estimates of the informal economy (Schneider et al., 2010).

This 'latent variable approach' provides comparable estimates of the size of the informal economy by treating

the informal economy as an unobservable latent construct measured by a series of indica tors and proximate

causes (Frey and Weck-Hanneman, 1984; Giles, 1999; Schneider, 2005; Schneider et al., 2010).4 In the

study, the authors estimate the relative size of the informal economy for 162 countries over an 8-year period

(1999–2007) using a linear model based on the fol owing variables: size of the public sector, the Heritage

Foundation's Fiscal Freedom Index, the Heritage Foundation's Business Freedom Index (BFI), and GDP per

capita (Schneider et al., 2010: 453).5 I include two of the four variables (the BFI and size of the public

sector) from the estimation model in the regression models to create a more conservative test for the partial

effects of the main inde pendent variables. Due to missing data in the independent variables, the analysis

uses estimates for 74 countries. Based on these estimates, the size of the informal economy ranges from

8.4 percent (Switzerland 1999) to 68.1 percent of official GDP (Panama 2006) with an average size of 28.2 percent of official GDP.

Independent variables: international trade, investment, and world-system position

I examine the direct and conditional of three variables: trade openness, foreign capital effects pen etration,

and world-system position. Al independent variables are lagged by a year. Trade open ness is measured

as the summation of exports and imports as a percentage of total GDP. Data on imports and exports are

drawn from the World Development Indicator database (World Bank, 2012). The variable is transformed

using a natural log function in order to adjust for univariate outliers and non-normality.

Based on previous studies on foreign capital penetration and economic growth (Beer and Boswel , 2002;

Dixon and Boswel , 1996; Mahutga and Bandelj, 2008), foreign capital penetration is measured as the total

inward stock of FDI as a percentage of total GDP. Foreign capital penetra tion is transformed using a

natural log function in order to adjust for univariate outliers and non normality. I include the rate of inward

FDI, which is measured as the ratio of total inward FDI flows to total inward stocks of FDI, and domestic

investment, measured as gross capital formation as a percentage of official GDP. The inclusion of these

controls is based on the misspecification of models in the early foreign capital penetration literature (see

Dixon and Boswel , 1996; Firebaugh, 1996). Data on inward FDI are drawn from the World Investment

database (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 2009). Data on gross capital

formation are drawn from the World Development Indicators database (World Bank, 2012).

World-system position is based on the categorization developed by Snyder and Kick (1979) and updated

by Bol en (1983) and Bol en and Appold (1993). Based on the block modeling of four political and economic

networks (international trade, diplomacy, military interventions, and trea ties), countries are categorized into

three general world-system positions: core, semi-periphery, and periphery. This measure is preferred over

other world-system position measures for three rea sons. First, the Snyder and Kick measure is the most

utilized indicator of world-system position in

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google 430

International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54(5-6)

the sociological literature (eg Alderson and Nielsen, 1999; Beckfield, 2003; Lee et al., 2007; Lloyd et al.,

2009; Mahutga et al., 2011). Second, the measure classifies the largest number of countries compared

to alternative measures. Third, recent research finds that the Snyder and Kick measure exhibits greater

predictive validity than other world-systems measures for explaining national income inequality (Mahutga

et al., 2011). Given the disagreement over world-system position measurement (Babones, 2005; Lloyd

et al., 2009), I re-estimate the models using two alternative world-systems measures based on

international trade networks. The first measure uti lize bilateral trade in 15 ideal-typical industries and a

regular equivalence strategy for identifying structural roles (Mahutga and Smith, 2011). The second

measure utilizes al bilateral trade from 1980 to 1990 and a core-peripheral modeling approach (Clark

and Beckfield, 2009). Based on the Snyder and Kick measure, the sample contains 30 periphery, 26

semi-periphery, and 17 core countries.

Baseline model: economic regulation

Three measures of a country's regulatory environment are included in the first baseline model: (1)

business regulation, (2) quality of enforcement, and (3) size of the public sector. The Heritage

Foundation's (2009) BFI is used for measuring the intensity of economic regulation. The BFI is a

standardized multidimensional index based on a number of economic regulations governing the opening,

operating, and closing a business.6 Data on these economic regulations are drawn from World Bank's

Doing Business reports. The index is inversely measured, where higher scores (100) indicates complete

business freedom (little to no regulation) and lower scores (0) indicates no busi ness freedom (complete regulation).

For measuring the quality of enforcement, I use the 'Rule of Law Index' (RLI) from the Governance

Matters database (World Bank, 2009). The RLI is measured using aggregated survey data from

government officials, business owners, and corporate managers. In the survey, respond ents were

asked a series of questions aimed at accounting for

[the] perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and

in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as wel as the

likelihood of crime and violence. (Kaufman et al., 2009)7

Lower scores on the index indicate a lack of enforcement, while higher scores indicate consistent and

efficient enforcement of regulations.

Final y, public sector size is measured as the total final expenditures of al government expenses,

excluding military expenditures, as a percentage of GDP. Previous research shows that public

expenditures are associated with a growth in the size of informal economy in Germany during the 1970s

(Petersen, 1982). Data on government expenditures are drawn from the World Bank (2012)

World Development Indicators database.

Baseline model: economic development and labor market performance

The second baseline model accounts for the effects of economic development and labor market

performance by including the fol owing variables: (1) the national unemployment rate, (2) the 3-year

average growth rate, (3) industrialization, (4) and urbanization . The national unemployment rate is

measured as the share of the labor force that is without work but are available for and seek ing

employment. Data for unemployment were drawn from the World Development Indicator data base

(World Bank, 2012). The rate of unemployment is transformed by a natural log function in

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 431

order to adjust for univariate outliers and non-normality. Economic growth is measured as a union try's

average GDP growth rate over the previous 3 years. Data on economic growth are drawn from the World

Development Indicator database (World Bank, 2012). Size of the manufacturing sector is measured as the

value added from the manufacturing sector as a percentage of GDP. Data on the size of the manufacturing

sector are drawn from the World Development Indicators database (World Bank, 2012). Urbanization is

measured as the proportion of the total population living in urban areas. Data on urbanization come from the

World Population Prospects database (United Nations, 2008).

In addition to the previous three measures, I include indicators for level of development.

specific, I include indicators for whether a country is low-income or lower-middle-income based on the 2010

World Bank income group classification.8 Low-income countries are defined as countries with a per capita

gross national income (GNI) less than US$1025, while lower-middle income countries are defined as

countries with a GNI per capita greater than US$1025 and less than US$4035.9

Table 1 provides summary statistics for the dependent and independent variables. Estimation

The hierarchical structure of panel data violates the basic assumption of case independence for unbiased

estimation with ordinary least squares regression. More importantly, failing to account for the clustering of

observation in country panels increases the likelihood of a false positive in hypothesis testing. In addition, a

central problem in inference is the potential for omitted variable bias caused by model misspecification

(Halaby, 2004). If these issues are not accounted for, then the likelihood of bias estimates and standard

errors increases (Wooldridge, 2002). In order to esti mate unbiased standard errors and parameters, this

study utilizes generalized least square (GLS) models with random and fixed effects and clustered standard

errors that are heteroskedasticity consistent (Rogers, 1993).

The two most common GLS models for panel data are the random-effect model (REM) and fixed-effect

model (FEM). The REM utilizes between-country and within-country variation for estimating parameters and

includes a normal y distributed panel-specific error component for measuring random unobserved country-

specific heterogeneity. The FEM only utilizes within country variation for estimating parameters because

the model includes a vector of panel-specific intercepts for measuring time-invariant unobserved

heterogeneity. Since the REM only includes a single parameter for unobserved heterogeneity, it is more

efficient than the FEM, but it assumes that the random panel-specific error component is orthogonal to the

observed covariates in the model. If this assumption is violated, the REM is unbiased, but inconsistent,

which makes the FEM preferable. In order to test this assumption, researchers compare coefficients from

the consistent model (FEM) to coefficients from the efficient model (REM) and determine whether there is a

significant significant difference (Hausman, 1978). In the analysis, the coefficients of the REMs are found to

be significantly different than the coefficients of FEMs, which suggests that the strict exogeneity assumption

was not met and the FEM is preferable for consistent estimates.

Even though the REMs are inconsistent, they are preferred over FEMs for two reasons. First, the FEM is

unable of estimating parameters for time-invariant variables because these variables are perfectly col inear

with the panel-specific intercepts. Second, since most of the variation in the size of the informal economy is

between countries rather than within countries, FEMs may be unreliable (Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal, 2012:

258).10 However, given the inconsistency of the REMs, I also estimate the same models with fixed effects as a robustness check.11

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google

432 International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54(5-6) Table 1. Summary statistics. Variable Mean SD Minimum Maximum Size of the informal economy 28.18 13.90 8.40 68.10 88.30 Trade openness 61.33 15.87 456.65 42.47 86.69 Foreign capital penetration 0.68 1007.67 FDI rate .14 .14 ÿ.41 1.86 Domestic investment 21.40 4.44 10.67 42.54 .41 .49 0 Periphery first Semi-periphery .34 .47 0 first Urbanization level 65.49 19.94 10.32 100.00 18.13 6.43 2.27 35.01 Size of manufacturing sector 7.95 4.98 .70 31.20 Unemployment rate Lower middle income .27 .45 0 first Low income .33 0 .twelfth first 2.43 3.32 Three-year GDP growth rate ÿ15.16 11.88 Rule of law index .55 .96 -1.25 2.12 Business freedom index 69.79 12.52 39.80 100.00 15.28 5.07 4.48 30.50 Size of public sectors

SD: standard deviation; FDI: foreign direct investment; GDP: gross domestic product. N = 554.

I test for two other potential problems in panel data analysis: temporal autocorrelation and groupwise

heteroskedasticity. If both conditions are present, standard errors are likely bias and the likelihood of

committing Type 1 or Type 2 errors is increased. Based on a test first-order autocorrelation10

(Wooldridge, 2002) of the ful model, I found the data exhibits significant first-order autocorrelation (F =

39.395, p < .001).12 Next, I test for the presence of groupwise heteroskedastic ity, or unequal error

variance across countries. Based on a standard test for panel-level heteroske data (Baum, 2001), I

found that the residuals showed significant variation across countries.

In order to ensure valid inference of the REMs and FEMs, I use robust-clustered standard errors (Rogers,

1993). Additional y, to account for the potential spatial autocorrelation of countries in the same geographic

area, I include region fixed effects in the model. Results

The structure of the world economy, trade, investment, and the informal economy

Model 1 in Table 2 shows the unstandardized coefficients of trade openness, foreign capital pene

tration, and world-system position. The results from Model 1 confirm that, net of international trade and

foreign capital penetration, there is a significant difference in the average size of the informal economy

between core, semi-peripheral, and peripheral countries. The average size of the informal economy in

the core is 9 percent smal er than the average in the periphery and 7.2 percent smal er than the average

in the semi-periphery. Based on the results from Model 2, even when control ing for the regulatory

environment, internal development processes, and economic globalization, the average difference in the

size of the informal economy between the core and periphery is 13.7 percent, while the average

difference between the core and semi-periphery is 8.5 percent. These findings provide tentative support

for the general hypothesis that the informal economy is larger in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries

because formal production in these countries is dependent on the informal economy for maintaining and

reproducing a surplus of low-wage labor.

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 433

Table 2. Random-effect models of the size of the informal economy, 1999–2007. (2) (3) (4) (first) Trade openness (log) 3.368*** (.622) 2.394*** (.678) 2.119***(.579) ÿ.504 (.814) Foreign capital penetration .546* (.227) .441+ (.265) .154 (.235) .423 (.274) (log) Foreign direct investment .006 (.316) .219 (.340) .363 (.329) .209 (.329) rate. rate Domestic investment .044 (.037) .007 (.031) .002 (.029) .002 (.029) Peripherya 9,020** (3,055) 13.68** (4.291) 10,340* (4,186) 5,812 (5,795) Semi-peripherya 7,241* (2,900) 8.472* (3.502) 5,427 (3,458) ÿ2,557 (5,571) Periphery × foreign capital 1,009** (.371) penetration Semi-periphery × foreign .916* (.369) capital penetration Periphery × trade 1,885+ (.982) openness Semi-periphery × trade 2,617* (1,124) openness Urbanization level .225*** (.053) .223*** (.052) .227*** (.053) Size of manufacturing .003 (.038) .006 (.036) ÿ.006 (.040) sectors. sector Unemployment rate (log) ÿ.615* (.273) ÿ.640* (.267) ÿ.626* (.278) Economic growth rate .069*** (.018) .072*** (.017) .068*** (.018) Lower middle incomeb .513 (.312) .509 (.311) .526+ (.309) Low incomeb 1,397 (.885) 1.463+ (.837) 1,459+ (.864) Rule of law index ÿ.260 (.491) ÿ.462 (.515) ÿ.218 (.517) Business freedom index ÿ.003 (.008) .002 (.008) .003 (.008) Size of public sector .020 (.068) .007 (.064) .023 (.068) Constant

ÿ1,268 (3,307) ÿ12,960* (5,737) .222

ÿ9.091+ (5.307) ÿ5,083 (6,332) R2 .252 .260 .244

N = 554; n = 74; estimates for region fixed effects not shown. Robust-cluster standard errors in parentheses.

a Reference group is core countries.

bReference group is high- and upper-middle-income countries.

+p < .05 (one-tail); *p < .05 (two-tail); **p < .01 (two-tail); ***p < .001 (two-tail).

According to results from Model 1, trade openness exerts a positive effect on the size of the informal

economy, where a unit increase in the log of trade openness is associated with an expansion in the size of

the informal economy equal to 3.4 percent of official GDP . In Model 4, trade openness is interacted with

indicators for world-system position to test whether this positive effect varies by whether a country is located

in the periphery or semi-periphery. According to the results, trade openness exerts a positive effect on the

size of the informal economy in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries. specific, a unit increase in the log

of trade open ness is associated with an increase in the size of the informal economy equal to 1.3 percent

of the official GDP in peripheral countries and 2.1 percent of the official GDP in semi-peripheral countries,

control ing for al other variables. In core countries, a unit increase in the log of trade openness is associated

with a decrease in the size of the informal economy equal to 0.5 percent of official GDP. However, this

relationship is not statistical y significant. The findings suggest that trade openness does not affect the size

of the informal economy in core countries, which is consistent with the unequal exchange hypothesis.

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google 434

International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54(5-6)

Figure 3. Differences in the effect of trade openness on size of the informal economy.

Source: Data from Schneider et al. (2010) and Snyder and Kick (1979). GDP: gross domestic product.

Regression slopes from Model 4 in Table 2.

Figure 3 shows the relationship between trade openness and the size of the informal economy in

core, semi-peripheral, and peripheral countries based on the coefficients in Model 4. Trade open ness

exhibits a negative relationship with the size of the informal economy in core countries , but this

relationship does not exist in the population. hope, trade openness shows a positive relationship with the

size of the informal economy in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries. It is important to note that the

interaction effect between periphery and trade openness is marginal y significant (p < .10), which raises

some doubt over whether this effect exists in the population.

Overal , Figure 3 il ustrates the unequal exchange hypothesis that trade openness is only positively

associated with the size of the informal economy in the periphery and semi-periphery of world economy.

According to the results in Model 1, foreign capital penetration exerts a positive effect on the size of

the informal economy. For a unit increase in the log of FDI stock, the informal economy is larger by 0.5

percent of official GDP. In Model 3, this effect was conditioned by world-system position. Similar to the

conditional effect of trade openness, foreign capital penetration exhibits a positive effect on the size of

the informal economy in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries, but has no effect on the informal

economy in core countries. In peripheral countries, a unit increase in the log of FDI stock was associated

with a growth in the informal economy equal to 1.2 percent of official GDP. In semi-peripheral countries,

a unit increase in the log of FDI stock was associated with a growth in the informal economy equal to 1 percent of official GDP.

Figure 4 shows the relationship between foreign capital penetration and the size of the informal

economy in periphery, semi-periphery, and core countries. In core countries, foreign capital

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 435

Figure 4. Differences in the effect of foreign capital penetration on size of the informal economy.

Sources: Data from Schneider et al. (2010) and Snyder and Kick (1979). GDP: gross domestic product.

Regression slopes from Model 3 in Table 2.

penetration shown little to no association with the size of the informal economy and is notably insignificant,

which is consistent with the disarticulation hypothesis. In peripheral and semi peripheral countries, foreign

capital penetration shows a strong positive association with the size of the informal economy, and these

associations are significantly significant (p < .01). The results from the interaction model are consistent with

the predictions of disarticulation hypothesis, which states that foreign capital penetration only increases the

size of the informal economy in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries. Model sensitivity analysis

As previously discussed, the consistency of the random-effects model depends on the assumption that the

random country-specific error component is orthogonal to the observed covariates in the model. Since this

assumption is violated, I re-estimate the same models from Table 2 using a fixed-effects estimator. World-

system position is omitted from the FEMs in Table 3 because it is perfectly col inear with the country-specific

intercepts. Even though the indicators for world-system position are omitted from the models, the estimates

of the interaction effects are unbiased because the country-specific intercepts account for the effects of the

time-invariant variables (Al ison, 2009). Models 1–3 in Table 3 confirm the consistency of the direct effects

of international trade and foreign capital penetration as wel as the conditional effects of world-system

position on the relationships between international trade, foreign capital penetration, and the size of the

informality economy. economy. Based on the results, it appears that the

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google

436 International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54(5-6) .(5 . 7 3 4 0 + 2) 5 (ÿ9. 4.,1 ,0 4 7 30 2 1 85 82 3 3) ) * 7 ) ÿ(.1 4. 6 1 2 2) (9) 72 .(7 . ÿ 9 1. 5 8 91 * 78 0 * ) * 2 * 3 ( , 12 , 9 1 4 6 * 8 * ) WOMEN 536 3 ( ,.7 6 7 4 2 3 * ) ** .1 (. 1,7 26 6 8 35 6 6 1) 5 * .(0 (. 6( 1,0 9 4, 0 5. 76 24 03 7 5 8 9 0) 7 65 8 4* 8 +)* * .(7 . 0 3 3 5 + 9) 72 ÿ(3 4 ,8 6 5 1 9 2 ) (8) 1 ( ,.1 2 5 9 3 8 * ) ** N C aB ( N lne 20 adc rk 0 f 9 ie ) ld 536 .(0 . 7( 1 , 4 1 04 4 1., 1 30 8 9 1) 0 2 6 )* 4 + ) .(5 . 5 3 1 1 + 1) (7) 1 (..(. 8. 7 60 2 6 75 0 0 5) *9 * *) * * 536 1 (ÿ, 1.67 .0 1.,7 70 39 7 3 59 15 8 7)8 ) 2 ) ÿ(...1 6 61 0 2 39 4 5 4* 7 )* 1(,.3 7 4 6 8 4 + ) (6) ÿ(1 4 ÿ , 5 3 9,61 4 289 2 2 ) 7 63 WOMEN 479 4 ( ,9 1, 5 1 7 4 * 2*)* .1 (. 9 3 1 4 0) .4 (. 5 4 0 0 3) .(0 (. 1 6 29 6 7 31 7 1 5) 7 * * 1 (ÿ.. 1. 4,2 .0 4,.21 52 34 57 2 0 537 96 7) 3) ) * * .5 (. 1 2 5 4 * 3 ) (5) 63 ÿ(5.5 4 6 2 7 8 ) WOMEN 479 .5 (. 8 4 7 2 4) ÿ( 1 . 240 ,1, 8. 1 3 75 6 6 3 615 7 ) 61* 0 *)* * .6 (. 1 4 2 .6 1 3 98 * 18* 5) 5 * * ÿ(8 5 ,9 5 9 1 3 0 ) (4) 63 WOMEN 479 M aS (2a n0h d m i1u t1t h)g a .3 (. 3 3 8 2 6) .0 (. 0 0 7 3 0) .3 (. ÿ 3 25 8 5 67 8 7 6) 9 72 (3) Y 74 1(,9 1, 4 0 7 5 + 6 ) 2 ( ,8 1, 1 1 9 5 * 8 ) 554 .(2 (. 2 0 21 6 6 34 4 3 0) 4 * * .4 (. 8 3 0 3 1) .0 (. 0 0 6 3 1) .0 (. 1 0 2 3 2) .8 (. 9 3 7 6 * 8 ) .9 (. 5 3 2 5 ** 2) 74 (2) Y ÿ(6 5,,.5 043 76 8 8 15 4 ) 554 .(3 ÿ 2..5 .4 7 9 22 3 + 07 3) 3 ) ** Y 74 ÿ(7 5 ,7 4 2 8 0 4 ) (first) 554 S aK ( n i 1 y d c 9 d k 7 e 9)r .3 (. 5 3 1 3 3) F cp (lo aere pi n g)it eg atrn l a t ion F do irre e i c g t n D ino v m e e st st m ic e n t Periphery P × fcp e o r a ri e pn pt e h gatlre n ar ty i o n Table T o(lra po d eg)e n n ess in r v at estment periphery Sp × fc e o r a m ri e pn it e- ph gatlre n ar ty i o n P × tr o e a p ri d e p e n h n ersys Sp × tr o e a p m ri d e i e n - ph n ersys Constant

Country World- measure. Observations Number M in cvfrr 2 c sep n T;oltr n o c o a M ar o ab u ar d lni obtlu s onr e e ur a m d s dn l do b ets e r a -rh e s de ses. Semi- +p

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 437

inconsistency of REMs is preeminent due to the association between the random country-specific

error component and the variables in the baseline models.

A second concern of the analysis is the validity of the Snyder and Kick (1979) world-system position

measure (Babones, 2005; Lloyd et al., 2009). I re-estimate the REMs from Table 2 using two alternative

(and more recent) world-system position measures derived from the analysis of international trade networks

(Clark and Beckfield, 2009; Mahutga and Smith, 2011). The results from Models 4–9 in Table 3 are fairly

consistent with the models using the updated Snyder and Kick (1979) measure. However, it is important to

note the differences between the models using the Snyder and Kick measure and the models using the two

alternative measures. First, the direct and conditional effects of semi-periphery status are smal er, while the

effects of periphery status are larger in the models using the Mahutga and Smith (2011) world-system

position measure com pared to the models using the Snyder and Kick ( 1979) measure. Second, the direct

effect of periphery status is larger, while the direct and conditional effects of semi-periphery status are

smal er in the models using the Clark and Beckfield (2009) measure compared to the models using the

Snyder and Kick (1979) measure . These differences in effect size are mainly attributed to differences in the

classification of countries and differences in samples.13 The stronger effects with the alterna tive world-

system position measures suggest that trade-based classification are more valid for approximating structural

roles in the world economy . Overal , the results are consistent with fixed effects estimation and alternative

measures of world-system position. Discussion and conclusion

In this article, I argue that the informal economy is a critical component of peripheral accumula tion. Since

periphery and semi-periphery countries specialize in labor-intensive and competitive industries (Chase-Dunn,

1989; Mahutga and Smith, 2011), firms in these countries require a sur plus of low-wage labor for profitable

production. specifical y, the informal economy is necessary for subsidizing low-value labor-intensive

production in the periphery and semi-periphery by pro viding inexpensive informal labor, a secondary

market for inexpensive goods and services for the reproduction of low-wage labor; and by suppressing the

wages of formal workers (Portes, 1978; Portes and Walton, 1981). Therefore, the informal economy is larger

in the periphery and semi periphery compared to the core.

The findings of the study suggest that cross-national variation in the size of the informal economy is

mainly attributed to the structure and processes of the world economy. The substantial difference in the size

of the informal economy between peripheral, semi-peripheral, and core coun tries provides empirical

support for the general argument that informal economy is a key compo nent of peripheral capitalism in the

world economy. Additional y, the results show that processes of world economic exchange are important

determinants of the size of the informal economy, but these effects vary by a country's location in the

structure of the world economy. Since peripheral and semi-peripheral countries mainly export labor-intensive

manufacturing goods and raw materials, international trade induces local firms to utilize low-cost labor to

earn a profit. Likewise, given these countries' specialization in labor-intensive industry, the inflow of foreign

capital into export-oriented sectors causes the informal economy to grow through the disarticulation of export

oriented sectors from the rest of the local economy.

An important consideration is the significant mean difference between core, periphery, and semi-periphery

countries after accounting for the effects of international trade and foreign capital penetration. Based on the

results, other unobserved processes associated with a country's structural location in the world economy

appear to affect the size of the informal economy. A limitation of this study is the inability to account for these

unobserved factors. Future research should identify

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google 438

International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54(5-6)

what other processes are associated with the reproduction of peripheral accumulation. Additional y,

another limitation of this study is the assumption that informal workers earn less than their formal

counterparts. Given the controversy over the relationship between formal and informal wages (Maloney,

2004), future research should scientifical y analyze whether large informal economies depress wages in

the formal economy. This line of research is critical for confirming whether the informal economy is an

essential component for reproducing low-wage regimes in the periphery and semi-periphery.

In countries located in the core of the world economy, international trade and investment show no

relationship with the size of the informal economy. Unlike peripheral and semi-peripheral coun tries,

production processes in the core are not dependent on the availability of a large surplus of low-wage

labor. Instead, profit accumulation in the core is dependent on the returns to capital and monopoly rents

because core countries tend to specialize in capital-intensive and high-value indus tries (Chase-Dunn,

1989). Therefore, the development of the informal economy in the core may be driven by immigration

into urban centers and the growth of petty producers. The informal economy provides low-cost goods

and services to migrant and impoverished populations in urban cent ers who may be unable to ful y

participate in the formal economy (Sassen, 1997, 2001). In order to test these claims, future research

should analyze the effects of international migration, immigration policy, and economic regulations on

the informal economy in core countries.

According to the results, the informal economy in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries is driven

by world economic processes. International trade and foreign investment induce local firms to utilize

goods, services, and labor from the informal economy because peripheral and semi peripheral countries

specialize in competitive industries and labor-intensive production. The infor mal economy 'subsidizes'

the costs of the formal economy in the periphery and semi-periphery with inexpensive labor, goods, and

services (Portes, 1978). This subsidy is essential for the profits of local firms and for the reproduction of

low-wage informal and formal labor in the periphery and semi-periphery. Based on the results of this

study, I conclude that the informal economy is an integral part of global capitalism because it facilitates

profit accumulation in the periphery and semi-periphery.

As peripheral and semi-peripheral economies are increasingly integrated into the world economy

through international trade and investment, the demand for a surplus of low-wage labor wil rise (Carr

and Chen, 2002; Phil ips, 2011) because these countries are structural y induced to spe cialize in labor-

intensive production processes (Mahutga, 2006; Mahutga and Smith, 2011). Given this trend, the informal

economy wil likely grow as local firms become increasingly integrated into global production networks.

Future research needs to re-orient the structural perspective to account for how the emergence of global

production networks impacts the development of the informal economy (see Phil ips, 2011). By studying

how local firms in the periphery and semi-periphery are incorporated into global production networks,

researchers can better account for the structural dynamics driving the recent growth of the informal

economy in developed and less developed countries.

alternatively, based on the results, internal developmental processes partial y explain cross national

variation in the size of the informal economy. specifical y, the rapid urbanization of the periphery and

semi-periphery, induced by internal migration from rural to urban centers, appears to promote the

development of the informal economy (Smith, 1987). In general, an increase in the size of the urban

population increases the demand for informal goods and services as wel as infor mal housing (Sassen,

1997, 2001). Since peripheral capitalism is more reliant on low-wage labor, urbanization should have a

greater effect on the informal economy in periphery and semi-periphery countries. Future research should

examine the differences in the relationship between spatial devel opment and the informal economy

across the structure of the world economy.

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015 Machine Translated by Google Roberts 439

The persistence and recent expansion of the informal economy during a period of ubiquitous economic

growth raises questions about the relationship between the formal and informal econoy. Given the paucity

of cross-national studies of the informal economy, the literature on the informal economy mired in

disagreement over the determinants of informal economic development. Based on insights from the world-

system perspective, I show that the cross-national variation in the size of the informal economy is explained

by the structure of the world economy, international trade, and foreign investment. In particular, the results

of the study suggest that the informal economy is a component of peripheral accumulation and that

processes of international trade and investment are critical drivers of the development of the informal

economy in the periph ery and semi-periphery. As the globalization of production intensifies and the world

economy becomes increasingly integrated, the informal economy wil persist and expand in accordance with

the demand for low-wage labor. Therefore, it is imperative that researchers remain committed to investigating

the informal economy in the context of the world economy. Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Notes

1. This approach is based on the premise that informal economic activity is unobservable because it operates

outside of official accounting practices. Therefore, these researchers develop measurement models using

observable indicators of informal economic activity.

2. According to Chase-Dunn (1989), the categorical distinction between the core and periphery is misleading

because core countries contain elements of peripheral capitalism. specific, rather than represent ing

discrete areas of the world economy, Chase-Dunn (1989) argues that the 'core/periphery dimension is a

continuous variable between constel ations of economic activities …' (p. 207).

3. The fol owing countries are included in the analysis: Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh,

Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Canada, Chile, China, Costa Rica, Cyprus, Denmark,

Dominican Republic, Egypt, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Guatemala,

Honduras, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Republic of

Korea, Kuwait, Luxembourg, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mauritius , Mexico, Mongolia, Morocco, the Netherlands,

New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal,

Romania, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, Syrian Arab

Republic, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uruguay, Venezuela, and Vietnam.

4. Empirical investigation of the informal economy is complicated by the intentional concealment of infor mal

activities reducing the availability of reliable and precise estimations of its size (Portes and Hal er, 2005). In

order to estimate the size of the informal sector, two general methods have been developed – direct and

indirect. Direct measures employ voluntary surveys or tax auditing and other compliance methods (Schneider

and Enste, 2002). Indirect methods utilize macroeconomic indicators to estimate the size of the informal

sector. Four indirect approaches are commonly used: labor market approaches, the smal firm approaches,

household consumption approaches, and the microeconomic approach (Portes and Hal er, 2005). The latent

variable approach provides the best method for measuring the informal economy because it assumes the

informal economy is unobservable

5. See Schneider et al. (2010: 448–452) for a discussion of their methodology. In order to obtain absolute

measures of the informal economy, instead of relative measures, Schneider utilizes previous estimates

based on the currency-demand approach (Tanzi, 1980, 1983) to approximate the relative measure pro

duced by the latent variable approach.

6. See the appendix in the Heritage Foundation (2009) report on economic freedom for specific variables. variables.

Downloaded from cos.sagepub.com at Selcuk Universitesi on February 1, 2015