Preview text:

Tourism Management 52 (2016) 82e95

The effects of perceived service quality on repurchase intentions and

subjective well-being of Chinese tourists: The mediating role of relationship quality

Lujun Su a, Scott R. Swanson b, *, Xiaohong Chen a

a Business School Central South University, Collaborative Innovation Center of Resource-conserving & Environment-friendly Society and Ecological

Civilization, 932 Lushan South Street, Changsha Hunan, China

b Management and Marketing Department, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, Eau Claire WI 54701, USA H I G H L I G H T S

● We propose and test an integrated model with domestic Chinese hotel guests.

● Satisfaction fully mediates antecedent and outcome relationships.

● Identification partially mediates antecedent and outcome relationships.

● Hospitality firms can help satisfy self-definitional needs.

● Identification provides positive consequences. A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history:

The current study provides and tests an integrated model that examines two relationship quality con- Received 5 June 2014

structs (overall customer satisfaction, customer-company identification) as mediating variables between Received in revised form

Chinese tourists' lodging service quality perceptions and two outcomes (repurchase intentions, subjec- 6 June 2015 Accepted 16 June 2015

tive well-being). The results of a study with domestic Chinese hotel guests (n ¼ 451) provide support for the proposed model. Speci Available online xxx

fically, the results indicate that overall customer satisfaction fully mediates the

relationship between perceived service quality and repurchase intentions and subjective well-being,

respectively. Customer-company identification partially mediates the relationship between perceived Keywords:

service quality and repurchase intentions and subjective wellbeing, respectively. We provide empirical Service quality Customer satisfaction

validation that customers do, indeed, identify with hospitality providers, and this, in-turn, provides Customer-company identi

positive consequences for both the service provider (i.e., repurchase intentions) and the customer (i.e., fication Repurchase intentions

subjective well-being). Managerial implications are provided, limitations noted, and future research Subjective well-being directions suggested.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction

more of their defecting customer base. The improved financial re-

wards are accrued through reduced customer acquisition market-

Customer relationships, and relationship marketing in partic-

ing costs, acquisition of new customers via positive word-of-

ular, have received considerable attention from both academicians

mouth, and larger purchases over time by less price-sensitive

and practitioners. Relationship marketing aims to build long-term,

loyal customers (Smit, Bronner, & Tolboom, 2007). Building

trusting, mutually beneficial relationships with valued customers

committed customer relationships “is increasingly emerging as a

(Kim & Cha, 2002). According to Reichheld and Sasser (1990),

strategy for organizations that strive to retain loyal and satisfied

companies can increase profits by almost 100% by retaining just 5%

customers in today's highly competitive environment” (Meng & Elliott, 2008, p. 509).

A social identity perspective can be useful to help establish the * Corresponding author.

relationship between companies and customers (Bhattacharya &

E-mail addresses: sulujunslj@163.com (L. Su), swansosr@uwec.edu

Sen, 2003). As such, customer-company identification is a

(S.R. Swanson), csu_cxh@163.com (X. Chen).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.012

0261-5177/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. /

potentially useful construct for better understanding customer re-

research in tourism/hospitality has not examined the potential

lationships, yet there have been few studies that examine it in this

mediating role of customer-company identification as a relational

way (Ahearne, Bhattacharya, & Gruen, 2005). In addition, few construct.

studies pay attention to social identification antecedents (e.g.,

Third, this study not only examines customer repurchase in-

identification) to customer behaviors and have not yet incorporated

tentions as an economic outcome, it also proposes and investigates

them into established frameworks (He, Li, & Harris, 2012; Martínez

customer subjective well-being as a social outcome of service

& Rodriguez del Bosque, 2013). Ahearne et al. (2005) point out that

evaluation perceptions. This study extends previous service-based

customer-company identification may have a greater effect when

relationship marketing studies by broadening the traditional

the offering is intangible, as in the case of services. Thus, it may be

research perspective that focuses only on economic outcomes.

worthwhile to examine customer-company identification in a

Although the study of subjective well-being has received increased hospitality services context.

attention among tourism researchers (e.g., Dolnicar et al., 2012;

Hotels can provide a wide range of tourist services such as ac-

Gilbert & Abdullah, 2004; Neal, Sirgy, & Uysal, 1999; Neal et al.,

commodation, food service, entertainment, local transportation,

2007; Sirgy, Kruger, Lee, & Yu, 2011), few studies have yet to

site recommendations, and arrangements for local tours. Thus, the

explore the antecedents and mechanism of tourists' subjective

hotel service experience is an important component of the entire

well-being. This study proposes perceived service quality, as an

tourism experience that, in some circumstances, may be reflective

antecedent of customer subjective well-being, and relational

of the overall tourism industry.

quality (i.e., overall customer satisfaction, customer-company

Leisure activities, including tourism, and their importance to life

identification) as both antecedents to customer subjective well-

satisfaction and a sense of well-being have been previously noted in

being and mediators of perceived service quality.

the tourism/leisure literature (e.g., Diener & Suh, 1997; Dolnicar,

In the following sections, we first utilize prior literature to

Yanamandram, & Cliff, 2012; Hobson & Dietrich, 1994; Karnitis,

construct a conceptual model that examines two relationship

2006; Neal, Uysal, & Sirgy, 2007, 2009). Milman (1998) points out

quality constructs (customer satisfaction, customer-company

that “an increasing number of tourism and travel promotional

identification) as mediating variables between the lodging service

campaigns suggest that travel, vacation, or any tourism experience

quality perceptions of Chinese tourists and two outcomes

may have a positive impact on a traveler's psychological well-be-

(repurchase intentions, subjective well-being). In the course of the

ing” (p. 166). However, the majority of studies in this area focus on

literature review, we also develop the hypotheses. The results

the relationship of quality of life or the subjective well-being of

follow, and the paper concludes with a discussion of the managerial

residents of tourism destinations, with few studies exploring the

implications of the findings, as well as study limitations and di-

contribution of specific tourism activities to tourists' subjective rections for future research.

well-being. Specially, it remains unclear whether tourism activities

facilitated by hospitality organizations contribute to tourists' sub-

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

jective well-being (Dolnicar et al., 2012).

With Asia predicted to be the world's largest tourist destination 2.1. Service quality

and tourist-generating region by 2020, it is surprising that there

has been a general lack of empirical studies with Asian tourists.

Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1988) define service quality

Notably, until China opened its doors to the outside world in 1978,

as the difference between customer expectations of the service to

tourism in the country was virtually non-existent. China has since

be received and perceptions of the actual service received. Based on

become a major tourism market (Lee & Sparks, 2007; Qiu & Lam,

this conceptualization, Parasuraman et al. (1988) developed a ser-

2004). With China's population of over 1.3 billion, tourism au-

vice measurement scale (i.e., SERVQUAL) which includes five

thorities have been focusing more attention on developing China's

quality dimensions (reliability, responsiveness, assurance,

domestic tourism market (Wang & Qu, 2004). The domestic market

empathy, and tangibles). SERVQUAL has been widely accepted by

now makes up more than 90% of the country's tourist traffic and has

scholars, but also criticized for its weaknesses and practical appli-

exhibited continuous growth of around 10% each year in the most

cation (Cronin & Taylor, 1992). In the tourism/hospitality literature,

recent decade (China Travel Guide, 2014). Thus, our theoretical

scholars have developed several domain-specific service quality

model is tested with structural equation modeling (SEM) using a

scales such as LODGSERV (Knutson, Stevens, Wullaert, Patton, & sample of Chinese tourists.

Yokoyama, 1990; Patton, Stevens, & Knutson, 1994), HOLSERV

The current study makes a number of contributions to the

(Mei, Dean, & White, 1999), Lodging Quality Index (Getty & Getty,

tourism/hospitality literature. First, it tests and demonstrates that

2003), and others (e.g., Akbaba, 2006; Albacete-Sa´ez,

perceived service quality plays a significant indirect role in the

FuenteseFuentes, & Llore´ns-Montes, 2007; Ekinci & Riley, 1998;

development of improved repurchase intentions, as well as greater

Tsang & Qu, 2000; Wilkins, Merrilees, & Herington, 2007).

customer subjective well-being in a lodging context. Previous

literature focused on service quality (e.g., Babin, Lee, Kim, & Griffin,

2.2. Relationship quality

2005; Hutchinson, Lai, & Wang, 2009; Kozak & Rimmington, 2000;

Petrick, 2004) has examined the relationship between service

Some authors suggest that relationship quality lacks both a

quality and customer behaviors, but has failed to examine customer

formal definition as well as agreement on what dimensions it

subjective well-being as a consequence.

consists of (e.g., Athanasopoulou, 2009; Huntley, 2006; Woo &

Second, this study incorporates customer-company identifica-

Ennew, 2004), although it is recognized as a higher order

tion as a relationship quality construct and tests its mediating role

construct consisting of several distinct constructs (Dwyer & Oh,

in the effects of service quality on customer repurchase intentions

1987; Kumar, Scheer, & Steenkamp, 1995; Lages, Lages, & Lages,

and subjective well-being. This study, thus, extends our under-

2005). Relationship quality is widely recognized as both a key to

standing of relationship quality by adding customer-company

developing loyal customers (Walsh, Hennig-Thurau, Sassenberg, &

identification as a relational construct. Bhattacharya and Sen

Bornemann, 2010) and an important predictor of customer post-

(2003) suggest that customer-company identification represents a

epurchase behavior (Crosby, Evans, & Cowles, 1990; Kim & Cha.,

deep, committed, and meaningful relationship between company

2002; Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Whereas service quality is an over-

and customer. To the best of our knowledge, previous empirical

all evaluation of a firm's performance, relationship quality is a /

strategic orientation that focuses on improving customer

meaningful customer relationships, yet few empirical studies have relationships.

investigated either the antecedents and/or consequences of

Prior research has investigated a number of distinct relationship

customer-company identification (Keh & Xie, 2009), particularly in

quality constructs such as commitment (Dorsch, Swanson, & Kelley,

a tourism/hospitality service context.

1998; Hennig-Thurau & Klee, 1997; Rauyruen & Miller, 2007;

Service quality perceptions have been tied to a number of pos-

Sevensson, Mysen, & Payan, 2010; Walsh et al., 2010) and trust

itive customer behaviors, yet this relationship is not necessarily

(Bejou, Wray, & Ingram, 1996; Dorsch et al., 1998; Dwyer & Oh,

straightforward. Using a value profit chain perspective would

1987; Kim & Cha, 2002; Moorman, Zaltman, & Deshpande, 1992;

suggest that both customer satisfaction and customer-company

Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Rauyruen & Miller, 2007; Sevensson et al.,

identification would be largely influenced by the perceived value

2010; Walsh et al., 2010). Different authors have also utilized a

that obtaining quality service provides to the customer. In addition,

variety of construct combinations to indicate relationship quality.

a cognitive-emotional-behavioral framework would also support a

For example, Lages et al. (2005) represented relationship quality as

perceived service quality to customer-company identification

the amount of information sharing, communication quality, long-

relationship. Though the impact of service quality on satisfaction

term orientation, and satisfaction with a relationship. Whereas

has been widely examined in previous literature, the potential ef-

Kumar et al. (1995) conceptualized relationship quality as encom-

fect of service quality on customer-company identification has not

passing conflict, trust, commitment, willingness to invest in a

been empirically explored fully. He and Li (2011) indicate that the

relationship, and expectation of continuity. In this study we

more favorable the perception of a service, the greater the level of

examine two distinct dimensions of relationship quality: customer

identification with a service company. Ahearne et al. (2005) posit

satisfaction and customer-company identification.

that “identification is likely to be stronger when customers have

favorable perceptions of the boundary-spanning agent with whom

2.2.1. Customer satisfaction

they interact (e.g., the company's salesperson, customer service,

Oliver (1997) conceptualized customer satisfaction as the cus-

technical representatives, etc.)” (p. 575). Underwood, Klein, and

tomer's fulfillment response: a judgment that a product or service

Burke (2001) indicate that characteristics of the servicescape may

provides a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment. In

assist consumers in developing social identification. Similarly,

the tourism/hospitality literature, prior studies have confirmed that

Ahearne et al. (2005) suggest that consumer perceptions of sales-

customer satisfaction is an important antecedent of key post-

person characteristics can also contribute to the development of

epurchase loyalty intentions and behaviors (Chen & Chen, 2010;

customer-company identification.

Chi & Qu, 2008; Hutchinson et al., 2009; Kozak & Rimmington,

Based on these previous findings, the current study posits the

2000; Su & Hsu, 2013; Su, Hsu, & Swanson, 2014). following hypothesis:

A number of prior studies suggest that service quality is a key

H1b. Perceived service quality has a positive in

determinant of customer satisfaction (e.g., Chi fluence on & Qu, 2008; Cronin, customer-company identi Brady, fication.

& Hult, 2000; Fornell, Johnson, Anderson, Cha, & Bryant,

1996; Hutchinson et al., 2009; Kozak & Rimmington, 2000; Orel

& Kara, 2014). This has been confirmed in a number of tourism

contexts such as cruises (Petrick, 2004), restaurants (Babin et al.,

2.3. Repurchase intentions

2005), and golf tourism (Hutchinson et al., 2009). In view of

these prior results, it is hypothesized that:

Service and relationship quality have been found to act as an-

tecedents to a variety of important customer loyalty behaviors such

H1a. Perceived service quality has a positive influence on overall

as repeat purchase, positive word-of-mouth, and the propensity to customer satisfaction.

pay more (e.g., Cronin et al., 2000; Fornell et al., 1996; Hennig-

Thurau, Gwinner, & Gremler, 2002; Palmatier, Dant, Grewal, &

2.2.2. Customer-company identification

Evans, 2006; Wulf, Odekerken-Schroder, & Iacobucci, 2001; Zei-

Customer-company identification is derived from social identity

thaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, 1996). Understanding how tourism

theory and organization identification. Social identity theory

service evaluations affect economic outcomes is important. Indeed,

(Brewer, 1991; Tajfel & Turner, 1985) suggests that in articulating

service evaluation is confirmed as an important antecedent of

their sense of self, people typically go beyond their personal

behavioral intentions (e.g., Chen & Chen, 2010; Chen & Tsai, 2008;

identity to develop a social identity. Ashforth and Mael (1989)

He & Song, 2009; Hutchinson et al., 2009; Zˇabkar, Brenˇciˇc, &

conceptualize the person-organization relationship as organiza-

Dmitrovi´c, 2010), which are important predictors of economic

tion identification, or a person's perception of oneness with an performance.

organization. Organization identification is the degree to which

In the marketing services literature, many studies have

organizational members perceive themselves and the focal orga-

confirmed that satisfaction is a key antecedent of repurchase in-

nization as sharing the same defining attributes (Dutton, Dukerich,

tentions (e.g., Anderson & Sullivan, 1993; Chang & Chang, 2010;

& Harquail, 1994). This identification helps to satisfy the need for

Cronin & Taylor, 1992; Orel & Kara, 2014; Zeithaml et al., 1996). In

social identity and self-definition.

tourism/hospitality contexts, the relationship between satisfaction

Bhattacharya and Sen (2003) extended the organizational

and revisit intentions has also been widely confirmed in such areas

identification construct to a marketing context via a conceptual

as cruises (Petrick, 2004), golfing (Hutchinson et al., 2009), island

framework of customer-company identification. They suggest that

tourism (Prayag & Ryan, 2012), heritage tourism (Chen & Chen,

customer-company identification is the primary psychological

2010; Su & Hsu, 2013), rural tourism (Loureiro & Kastenholz,

substrate for the kind of deep, committed, and meaningful re-

2011), restaurants (Chang, 2013; Liu & Jang, 2009), and lodging

lationships that marketers are increasingly seeking to build with

(Kim, Kim, & Kim, 2009). Based on the previous findings, the

their customers. Customer-company identification has been

following hypothesis is proposed:

defined as “an active, selective, and volitional act motivated by the

H2a. Overall customer satisfaction has a positive influence on

satisfaction of one or more self-definitional needs” (Bhattacharya & repurchase intentions.

Sen, 2003, p. 77). There would appear to be desirable organizational

benefits to building and maintaining deep, committed, and

Similar to customer satisfaction, customer-company /

identification can also impact customer loyalty (Bhattacharya &

there are still questions to be addressed. Tourists have been found

Sen, 2003; He & Li, 2011; He et al., 2012; Marin, Ruiz, & Rubio,

to generally be in good spirits during the day their trip commences

2009; Martínez & Rodriguez del Bosque, 2013; Perez & Rodriguez

(Nawijn, 2010, 2011), and feel generally happy during their holiday

del Bosque, 2013). According to Social Identity Theory (Tajfel &

compared to everyday life (Nawijn, 2011). However, particular as-

Turner, 1979) and Self-Categorization Theory (Turner, Hogg,

pects of interactive services experienced during the process have

Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherel, 1987), customer-company identifica-

not been investigated although these are likely to affect tourist

tion orientates the customer to become psychologically attached to

subjective well-being (Neal et al., 2007).

and care about a company (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003), which in

In a health service setting, Dagger and Sweeney (2006) found

turn positively stimulates their loyalty (Marin et al., 2009; Martínez

that service satisfaction positively impacts perceived quality of life.

& Rodriguez del Bosque; 2013; Perez & Rodriguez del Bosque,

Similarly, Neal et al. (1999) found a relationship between the

2013). Findings by Ahearne et al. (2005) point out that “from a

importance of an individual's satisfaction with tourism experiences

social identity standpoint, once a customer identifies with a com-

and their overall quality of life. Neal, Sirgy, and Uysal (2004)

pany, purchasing that company's products becomes an act of self-

expanded on their previous study by examining the role of

expression” (p. 577). These prior findings lead us to propose the

tourism services and found that satisfaction with tourism services following hypothesis:

and experiences, trip reflections, satisfaction with service aspects of H3a. Customer-company identi

tourism phases, and non-leisure life domains all had an influence

fication has a positive influence on repurchase intentions.

on overall life satisfaction. As such, there is support for modeling

customer satisfaction as an antecedent to subjective well-being.

H2b. Overall customer satisfaction has a positive in 2.4. fluence on Subjective well-being subjective well-being.

Subjective well-being is a scientific term for how people eval-

Few studies have explored the relationship between customer-

uate their lives (Diener, Suh, & Oishi, 1997) and refers to the

company identification and subjective well-being. According to

appraisal of one's life as satisfactory (Diener, 1984). The subjective

Bhattacharya and Sen (2003), customer identification with a com-

evaluation of one's life can be based on purely cognitive or purely

pany will result in the customer becoming psychologically attached

affective bases, or it can be based on a combination of the two

to and caring about the firm. Doing so motivates the customer to

(Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). The affective component

interact positively and cooperatively with organizational members,

of subjective well-being refers to how people perceive the balance

helping them to satisfy one or more important self-definition needs

between their pleasant and unpleasant affects, such as joy and

(e.g., self-continuity, self-distinctiveness, and self-enhancement).

sadness. This phenomenon is termed “hedonic balance”

Social interactions constitute one of the ways that tourists can

(Schimmack, Radhakrishnan, Oishi, Dzokoto, & Ahadil, 2002).

contribute to their quality of life (Dolnicar et al., 2012). According to

Others may make judgments about their subjective well-being

attribution theory (Weiner, 1980, 1985, 1986, 1995), when cus-

based primarily on what they believe is important for the fulfill-

tomers' self-definition needs are satisfied, their subjective well-

ment of their goals. Subjective well-being can be conceptualized

being may increase. In line with these discussions, the following

based on experience in a particular domain (e.g., job, consumption, hypothesis is formulated:

family, tourism, health) or on satisfaction with life in general as a

H3b. Customer-company identification has a positive influence

culmination of an individual's current life circumstance (Dagger & on subjective well-being. Sweeney, 2006).

Kotler, Adam, Brown, and Armstrong (2003) note that marketers

should seek to “deliver superior value to customers in a way that

maintains and improves the consumer's and the society's well-

2.5. Mediating hypotheses

being” (p. 20). Using a social marketing perspective, organizational

performance is increasingly being measured by social as well as

Customer satisfaction has previously been found to mediate the

financial outcomes (Clarke, 2001; Tschopp, 2003). The social mar-

effect of service quality on a range of customer loyalty and behav-

keting concept, therefore, defines marketing activity, at least in

ioral intention constructs in a variety of contexts, including su-

part, on the basis of its impact on subjective well-being. Dagger and

permarkets (Orel & Kara, 2014), health services (Dagger & Sweeney,

Sweeney (2006) suggest that in a services context, subjective well-

2006), IT services (Akter, D'Ambra, Ray, & Hani, 2013), and retail

being may be the most relevant outcome of the consumption

(Walsh & Bartikowski, 2013). A recent tourism study that sampled process.

Chinese tourists found that destination satisfaction fully mediated

Researchers of the tourism industry have recently begun to put

the effect of service quality on both revisit intentions and positive

more focus on the social outcomes of tourism development in areas

word-of-mouth referrals (Su et al., 2014). Therefore, this present

such as tourists' quality of life (Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011; Neal

study puts forth the following hypothesis:

et al., 2007), subjective well-being (Filep, 2014), and happiness

H4a. Overall customer satisfaction mediates the in (Nawijn, 2011). fluence of

perceived service quality on repurchase intentions.

Subjective well-being does not conflict with the traditional

financial and growth-oriented objective of tourism and destination

Engaging in leisure activities can affect the emotional, intellec-

development; rather, it strengthens our understanding of the po-

tual, spiritual, and/or physical aspects of an individual's life, which

tential impacts of tourism-based services. Managers, marketers,

in turn may influence the individual's overall sense of well-being

and policy makers can positively impact the lives of tourists

(Dolnicar et al., 2012). More specific to the current study, service

through the subjective well-being concept (Andereck & Nyaupane,

satisfaction has previously been found to play a key mediating role

2011). Tourism-based experiences influence people's quality of life

between service quality and quality of life perceptions in both

(Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011) and improve their subjective well-

health (Dagger & Sweeney, 2006) and IT service contexts (Akter

being (Filep, 2014). Although the relevance of tourist experiences

et al., 2013). Based on these prior findings, we propose that tour-

impacting subjective well-being has been acknowledged (e.g.,

ist evaluations of hospitality-based service encounter quality and of

Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011; Neal et al., 2007; Sirgy et al., 2011),

overall service satisfaction may well affect the quality of life /

perceptions reported by Chinese tourists.

reliability, responsiveness, confidence, and communication) were

assessed with a single adopted question identi

H4b. Overall customer satisfaction mediates the in fied in a pilot study fluence of

(discussion to follow) as most representative of a particular

perceived service quality on subjective well-being. dimension.

A few studies have identified customer-company identification

The measurement of customer satisfaction relied on a three-

as a mediator for a variety of postepurchase consumer behaviors.

item scale adapted from Maxham and Netemeyer (2002). For

Bhattacharya and Sen (2003) suggest that customer-company

customer-company identification, we utilized the well-established

identification may mediate the effect of identity attractiveness on

scale by Mael and Ashforth (1992), which has previously shown

company loyalty, company promotion, customer recruitment, and

good reliability in a hotel industry context (So, King, Sparks, &

resilience to negative information. Hong and Yang (2009) report a

Wang, 2013). Three relevant items were selected from the orig-

critical mediating effect of customer-company identification be-

inal six based on pre-test findings (discussion of pilot study to

tween organizational reputation and customers' positive word-of-

follow). Repurchase intentions were measured via a three-item

mouth referrals. In a business-to-business context, Keh and Xie

scale derived from Arnold and Reynolds (2003). Subjective well-

(2009) confirmed customer-company identification mediates the

being was measured via three items adapted from the Subjective

effect of corporate reputation on purchase intention. Based on

Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999). All the aforemen-

these previous findings, the present study puts forward the

tioned measures were assessed via five-point, Likert-type scales following hypothesis:

with anchors of Strongly Disagree (1) and Strongly Agree (5).

To establish translation equivalence the questionnaire was H5a. Customer-company identi first

fication mediates the influence of

prepared in English, and the back translation process suggested by

perceived service quality on repurchase intentions.

Mullen (1995) was utilized to identify any content or wording er-

Service quality is an important predictor of customer-company

rors. Specifically, to establish translation equivalence, the ques-

identification (He & Li, 2011; Lam, Ahearne, & Schillewaert, 2012;

tionnaire was first prepared in English and then translated into

Underwood et al., 2001). Identification is based on an individual

Chinese by a native speaker. Back translation into English was

seeing him or herself as psychologically intertwined with the

performed by a second individual, and then the back-translated

characteristics of a group. Strong customer-company identification

English version and the original versions were compared. The

can help customers satiate one or more of their self-definitional

back translation process utilized a third [bilingual] individual to

needs (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003). Satisfaction of self-definitional

identify any content and wording errors.

needs should result in greater levels of subjective well-being. We

To better ensure the reliability of the measurement scales and

have not been able to identify any published studies that explore

reduce the overall number of scale items, a pilot study was first

the potential mediating role of customer-company identification

conducted with a convenience sample of 50 undergraduate busi-

between service quality and customer subjective well-being. Thus,

ness students from a university located in central China. Each of the

the following hypothesis is investigated:

student participants was pre-screened to ensure that they had

previously been guests at a full-service hotel. The pilot study re-

H5b. Customer-company identification mediates the influence of spondents

perceived service quality on subjective well-being.

first provided suggestions that resulted in some slight

wording changes for some of the scale items. Using SPSS 21.0, a

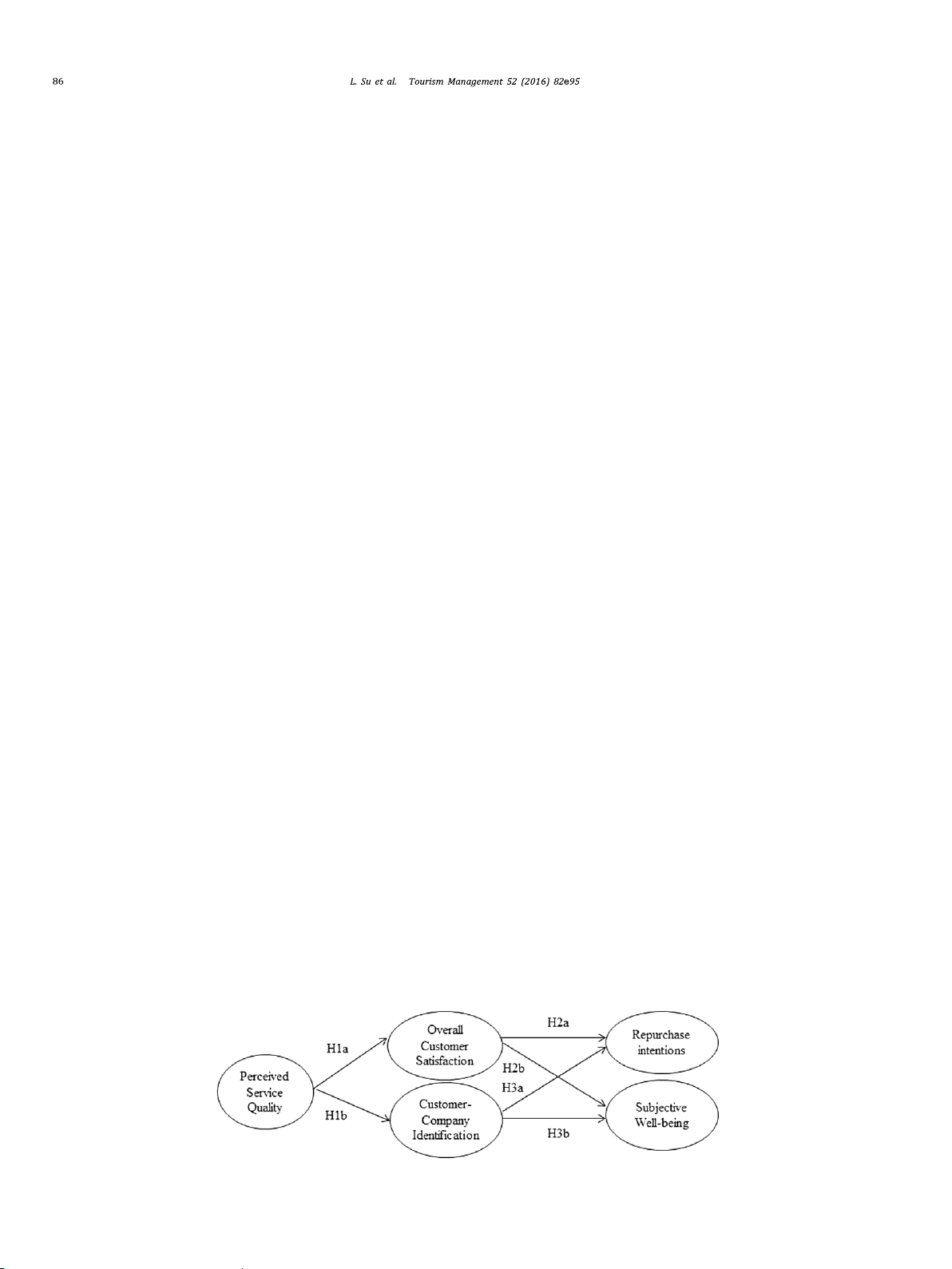

The conceptual model portraying the network of relationships

reliability analysis was conducted examining Cronbach's alpha

between relationship quality (overall customer satisfaction,

coefficient as well as the item-total statistics (i.e., corrected item-

customer-company identification), its antecedent (perceived ser-

total correlations; Cronbach's alpha if item deleted) to reduce the

vice quality), and consequences (repurchase intentions, subjective

original question pools. The goal was to create a questionnaire that

well-being) is provided in Fig. 1.

was as concise as possible to aid in reducing respondent fatigue and

encouraging participation. The investigated construct scales all

demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability in the pilot test (i.e., 3. Methodology

alpha >.70). Prior to the questionnaire being finalized, four man-

agers of full-service hotels and three faculty members familiar with

3.1. Construct measurement

the topic area also reviewed the questionnaire. Slight wording re-

visions were made based on their suggestions. When no further

Getty and Getty (2003) suggest that an assessment measure of

changes were recommended, the questionnaire was

hotel quality must include dimensions that re finalized for flect the unique na- use.

ture of the lodging industry. As such, they developed the lodging

quality index (LQI). The LQI is based on SERVQUAL (Parasuraman

et al., 1988), but is designed specifically to provide accurate 3.2. Data collection

customer feedback in a lodging context (Getty & Getty, 2003;

Ladhari, 2009). Each of the LQI quality dimensions (i.e., tangibles,

Data was collected from Chinese leisure visitors to Huitang

Fig. 1. Proposed conceptual model. /

Village, China. Located on the banks of the Wujiang River, this area

conducted to assess the reliability, convergent validity, and

of Hunan province is famous for both its scenic beauty and me-

discriminant validity of the latent constructs between service

dicinal hot springs. The administrator for the Bureau of Huitang

quality, customer satisfaction, customer-company identification,

Spring Resort provided permission to conduct the study in ex-

repurchase intentions, and subjective well-being. Hu and Bentler

change for receiving a report of the findings to share with the

(1999) caution that “it is difficult to designate a specific cutoff

participating hotels. The Bureau of Huitang Spring Resort admin-

value for each fit index because it does not work equally well with

istrator contacted three individual hotel managers who all agreed

various conditions” (p. 27). However, to assist with interpretation of

to allow the data collection to take place. Two trained researchers

the findings the following discussion is being provided. Values for

conducted the actual data collection process. The surveying took

the Root Mean Square Residual (RMR) can range from zero to 1.0

place in the lobbies of three different full-service upscale hotels

with well-fitting models obtaining values less than .05 (Byrne,

(i.e., Huatian Hot Spring Hotel, Jintaiyang Hot Spring Vacation

1998; Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2000), although values as high

Resort, and Zilongwan Hot Spring International Hotel).

as .08 are deemed acceptable (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Recommenda-

Potential subjects were approached and asked if they would be

tions for Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) cut-off

interested in completing a short questionnaire. If the hotel guest

points have been reduced considerably in recent years. Tradition-

gave a “yes” answer, the survey investigators would ask the

ally, an RMSEA value of less than .05 indicated good fit; in the range

respondent if they were familiar with the hotel and had experi-

of .05e.10 was considered an indication of fair fit, and values above

enced services provided by the hotel. Seating was available for re-

.10 indicated poor fit (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996).

spondents to sit and complete the questionnaires. The investigators

More recently, a cut-off value close to .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999) or a

stayed available nearby to provide any asked for clarifications while

stringent upper limit of .07 (Steiger, 2007) seems to be the general

respondents completed the questionnaire. Participation in this

consensus. According to Hair, Black, Babin, and Anderson (2010),

study was voluntary and participants' names and contact infor-

c2/df ratios of 3:1 or less are associated with better-fitting models

mation were not requested to protect the respondents' privacy.

when sample size is less than 750. Values of .90 or greater indicate

When retrieving the questionnaires from respondents each ques-

well-fitting models for the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) and the

tionnaire was briefly checked for completeness. The completed

Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) (Hooper, Coughlan, &

questionnaires were collected and provided to the primary

Mullen, 2008). For the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) a cut-off crite-

researcher of the study. Respondents were selected randomly, on

rion of .90 or greater is needed (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For samples of

different days of the week and at different times of the day between

250 or more and observed variables numbering between 12 and 30,

the hours of 9:00 am and 9:00 pm. The researchers distributed a

Hair et al. (2010) suggest a CFI of above .92. For the Normed Fit

total of 600 questionnaires over a two-month period, with 451

Index (NFI), Bentler and Bonnet (1980) suggest that values greater

returned that included complete responses (75.2% response rate).

than .90 indicate a good fit, while Hu and Bentler (1999) indicate

Respondents were all ethnic domestic Chinese and slightly more

that the cut-off criteria be greater than .95. The Relative Fit Index

likely to be female (50.3%). Age categories represented included 16

(RFI) and Incremental Fit Index (IFI) should be equal to or greater

to 24 (41.5%), 25 to 44 (42.1%), and 45 years of age or older (16.4%). A

than .90, while the TuckereLewis Index (TLI) recommendations

wide range of occupations were reported (e.g., business owner,

have had acceptable cutoffs noted as low as .80 (Hooper et al.,

farmer, public servant, sales person, soldier, student, teacher), with 2008).

the level of education ranging from less than high school (17.1%), to

a postgraduate degree (5.1%). The majority of reported individual

4.1.1. Goodness-of-fit measurement model

monthly incomes fell below 4000¥. Complete sample character-

According to the model evaluation criteria suggested in the prior

istics are provided in Table .1.

discussion, the overall fit of the proposed model to data was

acceptable (see Table 2). Specifically, c2/df ¼ 2.031, RMSEA ¼ .048, 4. Empirical analyses

RMR ¼ .025, GFI ¼ .945, AGFI ¼ .922, NFI ¼ .954, RFI ¼ .943,

IFI ¼ .976, TLI ¼ .970, CFI ¼ .976.

The reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of

the investigated constructs were assessed prior to testing the hy-

4.1.2. Reliability test

pothesized relationships in the proposed model.

Findings indicate that all constructs included in the proposed

model achieved acceptable levels of reliability based on Cronbach's 4.1. Measurement model

alpha coefficient exceeding .70 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981): service

quality (.867), customer satisfaction (.863), customer-corporate

To verify the underlying structure of constructs in the proposed

identification (.818), repurchase intentions (.929), and subjective

theoretical model we first conducted a confirmatory factor analysis

well-being (.872). Similarly, composite reliability of the latent

(CFA). Measurement model tests using AMOS 21.0 software were

constructs ranged from .819 to .933 (see Table 2). Table 1 Sample characteristics. n % n % Gender Age in Years Female 224 49.7 16 to 24 187 41.5 Male 227 50.3 25 to 44 190 42.1 45 or Older 74 16.4 Monthly Income Less than 2000¥ 90 20.0 Level of Education 2000 to 2999¥ 96 21.3 Less than High School 77 17.1 3000 to 3999¥ 114 25.3 High School/Technical School 145 32.2 4000 to 4999¥ 69 15.3

Undergraduate/Associates Degree 206 45.7 5000¥or More 82 18.2 Postgraduate Degree 23 5.1 / Table 2

Confirmatory factor analysis results. Latent and observed Variables Mean SD Standard loading t-statistic CR AVE Cronbach's alpha Service Quality

The hotel was visually appealing 3.62 .85 .733 17.211 .867 .567 .867

My reservation was handled efficiently 3.60 .79 .787 19.008

Employees responded promptly to my requests 3.62 .82 .710 16.452

The hotel provided a safe environment 3.48 .84 .761 18.136

Charges on my account were clearly explained 3.56 .86 .772 18.498 Customer Satisfaction

As a whole, I am satisfied with (hotel name) 3.66 .80 .823 20.427 .864 .680 .863

I am satisfied with the overall service that (hotel name) provided to me 3.52 .79 .837 20.943

I am satisfied with my overall experience with (hotel name) 3.53 .85 .814 20.113

Customer-company Identification

I am very interested in what others think about (hotel name) 3.60 .87 .733 16.547 .819 .602 .818

This hotel's successes are my successes 3.56 .88 .842 19.630

When someone praises this hotel, it feels like a personal compliment 3.21 .84 .748 16.966 Repurchase Intentions

I intend to revisit (hotel name) my next trip to this area 3.62 .94 .798 20.268 .933 .823 .929

(Hotel name) would always be my first choice 3.49 .90 .966 27.596

I would like to come back to (hotel name) in the future 3.47 1.00 .949 26.751 Subjective Well-Being

In general, I consider myself a very happy person 3.86 .69 .801 19.510 .875 .701 .872

Compared to most of my peers, I consider myself more happy 3.92 .67 .896 22.882

I am generally very happy and enjoy life 3.89 .71 .811 19.865

Goodness-of-fit: c2/df ¼ 2.031, RMSEA ¼ .048, RMR ¼ .025, GFI ¼ .945, AGFI ¼ .922, NFI ¼ .954, RFI ¼ .943, IFI ¼ .976, TLI ¼ .970, CFI ¼ .976.

4.1.3. Convergent validity test

follows: c2/df ¼ 2.227, RMSEA ¼ .052, RMR ¼ .039, GFI ¼ .940,

According to Anderson and Gerbing (1988), convergent validity

AGFI ¼ .918, NFI ¼ .948, RFI ¼ .937, IFI ¼ .971, TLI ¼ .965, CFI ¼ .971.

is satisfied if the standardized factor loading exceeds .400, is sig-

In comparison with values suggested in the prior discussion, find-

nificant at .001, and average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than

ings demonstrate that the model's fit is satisfactory. Thus, it was

.500. As provided in Table 2, the standardized factor loading of

deemed appropriate to next test the hypothesized paths.

items ranged from .710 to .967, and all were statistically significant

(p < .001). Average variance extracted of the latent constructs

4.2.2. Structural model results

ranged from .567 to .823. The findings suggest that a large portion

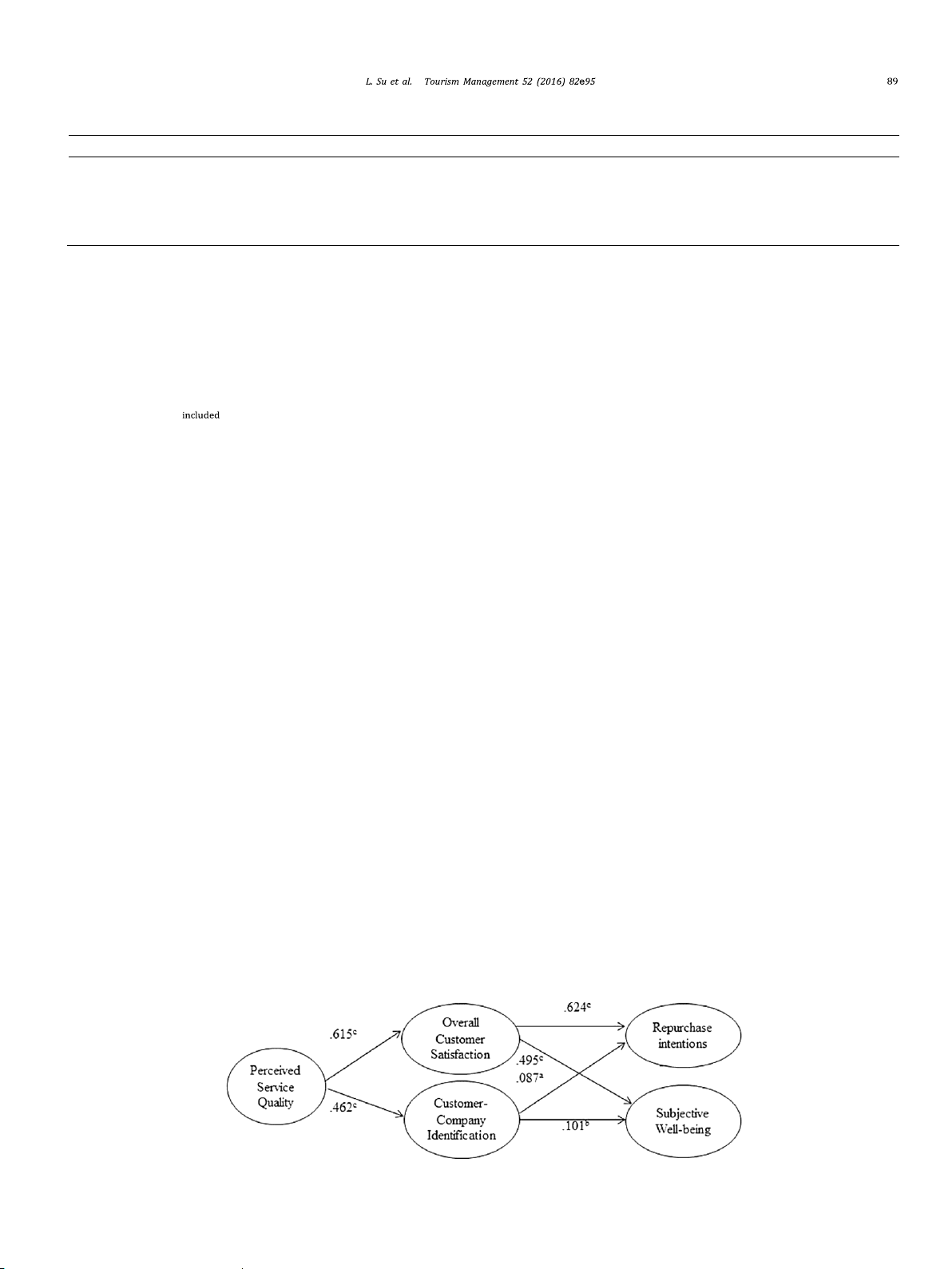

The hypothesized positive relationship between service quality

of the variance was explained by the items, and convergent validity

and customer satisfaction (H1a) was supported (l21 ¼ .615, is satisfied.

t ¼ 11.145, p < .001). Hypothesis H1b, which predicted a positive

relationship between service quality and customer-company

4.1.4. Discriminant validity test

identification was also supported (l31 ¼ .462, t ¼ 8.291, p < .001).

According to Chin (1998), discriminant validity is satisfied if the

As predicted by hypotheses H2a and H2b, customer satisfaction

AVE is greater than .500, and the correction coefficient among

significantly impacted both repurchase intentions (b42 ¼ .624,

latent constructs is lower than the squared root of AVE. Construct

t ¼ 11.746, p < .001) and subjective well-being (b52 ¼ .495, t ¼ 8.916,

AVE ranged from .567 to .823, all exceeding .500 (see Table 2). The

p < .05). Customer-company identification was also found to have a

square root of AVE of the latent constructs ranged from .753 to .907,

statistically significant positive influence on repurchase intentions

while the correlation coefficients among latent constructs fell be-

(b43 ¼ .087, t ¼ 1.942, p < .1) and subjective well-being (b53 ¼ .101,

tween .322 and .664 (see Table 3). The findings indicate adequate

t ¼ 1.966, p < .05), providing support for both H3a and H3b. The discriminant validity.

predicted relationships, standardized path loadings, t-values, and

hypotheses test outcomes are provided in Table 4.

4.2. Structural path model

4.3. Power of the model

Once the measurement model was validated, subsequent

structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses were conducted to

According to Cohen (1988) the value of R2 (.01, .09, and .025) can

support the theoretical model and to test the hypotheses.

be used as threshold values to demonstrate small, medium, and

large effects in behavioral models. In the current study, results

4.2.1. Structural model fitting index

suggest that large impacts on the endogenous variables are being

The fitting indices of the structural path model results are as

captured in the model (see Fig. 2), specifically, 37.8%, 21.4%, 42.7% Table 3

Correlation matrix and average variance extracted. Perceived service Overall customer Customer-company Repurchase intentions Subjective well being quality satisfaction identification Service Quality .753 Customer Satisfaction .601 .825

Customer-Company Identification .436 .495 .776 Repurchase Intentions .399 .664 .368 .907 Subjective Well-Being .363 .539 .322 .325 .837

Note: square root of average variance extracted (AVE) is shown on the diagonal of the matrix; inter-construct correlations are shown off the diagonal. / Table 4

Structural model evaluation indices and hypotheses test outcomes. Hypothesis Predicted relationships

Path label Standard Path loadings

T-value Standard error Hypothesis test outcome H1a

Perceived service quality / Overall customer satisfaction l21 .615c 11.145 .055 Supported H1b

Perceived service quality / Customer-company identification l31 .462c 8.291 .062 Supported H2a

Overall customer satisfaction / Repurchase intentions b42 .624c 11.746 .062 Supported H2b

Overall customer satisfaction / Subjective well-being b52 .495c 8.916 .047 Supported H3a

Customer-company identification / Repurchase intentions b43 .087a 1.942 .046 Supported H3b

Customer-company identification / Subjective well-being b53 .101b 1.966 .038 Supported

a Statistically significant (p < .1).

b Statistically significant (p < .05).

c Statistically significant (p < .001).

and 28.3% of the variance for customer satisfaction, customer-

on repurchase intentions and subjective well-being. The model fits,

company identification, repurchase intentions, and subjective

(c2/df ¼ 2.867, RMSEA ¼ .064, RMR ¼ .025, GFI ¼ .965, AGFI ¼ .937,

well-being, respectively. We calculated effect size (G2) by exam-

NFI ¼ .976, RFI ¼ .965, IFI ¼ .984, TLI ¼ .977, CFI ¼ .984), and the

ining the impact of each independent latent variable on each

standardized path coefficients are all statistically significant (see

dependent latent variable using the formula (G2 ¼ (R2

Table 5). Thus, Baron and Kenny's included — first criterion is met. R2excluded)/(1 — R2 ))

provided by Lee, Petter, Fayard, and

Secondly, the constructed structural equation model between

Robinson (2011). The effect size for overall customer satisfaction

perceived service quality and repurchase intentions and subjective

on repurchase intentions is .457. The effect size of overall customer

well-being was found to fit (c2/df ¼ 2.501, RMSEA ¼ .058,

satisfaction on subjective well-being is .213. The effect sizes of

RMR ¼ .043, GFI ¼ .960, AGFI ¼ .937, NFI ¼ .967, RFI ¼ .956,

customer-company identification on repurchase intentions and

IFI ¼ .980, TLI ¼ .973, CFI ¼ .980). The standardized path coefficients

subjective well-being are .016 and .010, respectively.

between perceived service quality on repurchase intentions and

subjective well-being were all statistically significant (see Table 6).

Thus, Baron and Kenny's second criterion is met.

4.3.1. Mediation effects of relationship quality

Next, we constructed a structural equation model including

To test for mediating effects, Baron and Kenny (1986) suggest

perceived service quality, repurchase intentions, and subjective

regressing the (1) mediators on the independent variables, (2)

well-being using overall customer satisfaction as a mediating var-

dependent variables on the independent variables, and (3)

iable (see Table 7). Modeling all direct and indirect paths (see

dependent variables on both the independent variables and me-

Table 8), the results indicate that the overall model fits, (c2/

diators. Based on the Baron and Kenny (1986) method, Hopwood

df ¼ 2.509, RMSEA ¼ .058, RMR ¼ .027, GFI ¼ .945, AGFI ¼ .920,

(2007) pointed out that a structural equation model method has

NFI ¼ .957, RFI ¼ .946, IFI ¼ .974, TLI ¼ .967, CFI ¼ .974). Service

advantages over multiple regression in testing mediating effects. It

quality has a significant effect on customer satisfaction, but not on

is not necessary that mediator models specify observed (measured)

repurchase intentions or subjective well-being. Customer satisfac-

variables, and in many cases there are advantages to specifying

tion is significantly associated with both repurchase intentions and

latent variables. Latent variables are commonly used in applications

subjective well-being. According to the judgment criterion of the

such as structural equation modeling (SEM). One advantage of us-

mediating role suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986), the results

ing latent, as opposed to observed, variables is that the former

indicate that customer satisfaction fully mediates the effect of

tends to estimate the desired effect more reliably because any

service quality on repurchase intentions and subjective well-being.

variables associated with measurement error in a particular

Using the same methods and procedures, we next tested for the

observed variable are unlikely to be shared across other observed

mediating role of customer-company identification. Having previ-

variable(s) and, thus, will not contribute to the score on a shared

ously identified that service quality significantly influences

latent variable (Hopwood, 2007). Thus, unreliability and method

repurchase intentions and subjective well-being, the constructed

effects on models of mediation can be ameliorated through the use

structural equation model between customer-company identifica-

of SEM (Hopwood, 2007). In the current study, all variables are

tion, repurchase intentions, and subjective well-being was found to

latent. So, following Baron and Kenny (1986) method and

fit (c2/df ¼ 1.663, RMSEA ¼ .038, RMR ¼ .052, GFI ¼ .980,

Hopwood's (2007) procedures, we test the mediating roles of

AGFI ¼ .964, NFI ¼ .984, RFI ¼ .977, IFI ¼ .993, TLI ¼ .991, CFI ¼ .993).

customer satisfaction and customer-company identification,

The standardized path coefficients were all statistically significant respectively.

(see Table 9). Baron and Kenny (1986) first criterion is met.

To test the mediating effect of customer satisfaction, we first

Next, the results of modeling all direct and indirect paths of

construct a structural equation model with customer satisfaction

Fig. 2. Structural Model Results. Note: aStatistically significant (p < .1). bStatistically significant (p < .05). cStatistically significant (p < .001). Note: aStatistically significant (p < .1). / Table 5

Standardized path coefficients between overall customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions and subjective well-being. Predicted relationships Standardized Path loadings T-value Standard error

Overall customer satisfaction / Repurchase intentions .658a 12.514 .063

Overall customer satisfaction / Subjective well-being .534a 9.849 .047

Goodness-of-fit: c2/df ¼ 2.867, RMSEA ¼ .064, RMR ¼ .025, GFI ¼ .965, AGFI ¼ .937, NFI ¼ .976, RFI ¼ .965, IFI ¼ .984, TLI ¼ .977, CFI ¼ .984.

a Statistically significant (p < .001). Table 6

Standardized path coefficients between perceived service quality and repurchase intentions and subjective well-being. Predicted relationships Standardized Path loadings T-value Standard error

Perceived service quality / repurchase intentions .408a 7.784 .060

Perceived service quality / subjective well-being .375a 6.884 .045

Goodness-of-fit: c2/df ¼ 2.501, RMSEA ¼ .058, RMR ¼ .043, GFI ¼ .960, AGFI ¼ .937, NFI ¼ .967, RFI ¼ .956, IFI ¼ .980, TLI ¼ .973, CFI ¼ .980.

a Statistically significant (p < .001). Table 7

Standardized path coefficients between perceived service quality on overall customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions and subjective well-being. Predicted relationships Standardized Path loadings T-value Standard error

Perceived service quality / Overall customer satisfaction .599a 10.819 .055

Perceived service quality / Repurchase intentions .005 .090 .065

Perceived service quality / Subjective well-being .068 1.069 .053

Overall customer satisfaction / Repurchase intentions .657a 10.247 .075

Overall customer satisfaction / Subjective well-being .494a 7.316 .057

Goodness-of-fit: c2/df ¼ 2.509, RMSEA ¼ .058, RMR ¼ .027, GFI ¼ .945, AGFI ¼ .920, NFI ¼ .957, RFI ¼ .946, IFI ¼ .974, TLI ¼ .967, CFI ¼ .974.

a Statistically significant (p < .001). Table 8

Direct, indirect, and total effects of service quality on overall customer satisfaction, repurchase intention, and subjective well-being. Predicted relationships Direct effects Indirect effects Total effects

Perceived service quality / Overall customer satisfaction .599a e .599a

Perceived service quality / Repurchase intentions .005 .394a .399a

Perceived service quality / Subjective well-being .068 .296a .364a

Overall customer satisfaction / Repurchase intentions .494a e .494a

Overall customer satisfaction / Subjective well-being .657a e .657a

a Statistically significant (p < .001).

service quality, customer-company identification, repurchase in-

5. Conclusions and discussions

tentions, and subjective well-being are provided (see Tables 10 and

11). The overall model fits (c2/df ¼ 1.719, RMSEA ¼ .040, 5.1. Discussion

RMR ¼ .032, GFI ¼ .962, AGFI ¼ .945, NFI ¼ .967, RFI ¼ .958,

IFI ¼ .986, TLI ¼ .982, CFI ¼ .986), and H5a and H5b are confirmed.

The current study provides and tests an integrated model that

Service quality has a significant effect on customer-company

examines two relationship quality constructs (customer satisfac-

identification, repurchase intentions, and subjective well-being,

tion, customer-company identification) as mediating variables be-

respectively. Customer-company identification also significantly

tween the lodging service quality perceptions of Chinese tourists

impacts repurchase intentions and subjective well-being. Based on

and two outcomes (repurchase intentions, subjective well-being).

suggestions by Baron and Kenny (1986), the results indicate that

Previous research on relationship quality has tended to ignore the

customer-company identification partially mediates the effect of

role of customer-company identification even though it represents

service quality on repurchase intentions and subjective well-being.

deep, committed, and meaningful relationships (Bhattacharya &

We summarize the results regarding the mediating effects of

Sen, 2003) and a close bonding (Keh & Xie, 2009) between a

customer satisfaction and organizational identification in Table 12.

company and its customers. In addition, although subjective well-

being research has received increased attention among tourism

researchers (Dolnicar et al., 2012; Gilbert & Abdullah, 2004; Neal Table 9

Standardized path coefficients between customer-company identification and repurchase intentions, subjective well-being. Predicted relationships Standardized Path loadings T-value Standard error

Customer-company identification / repurchase intentions .381a 7.139 .055

Customer-company identification / subjective well-being .338a 6.094 .041

Goodness-of-fit: c2/df ¼ 1.663, RMSEA ¼ .038, RMR ¼ .052, GFI ¼ .980, AGFI ¼ .964, NFI ¼ .984, RFI ¼ .977, IFI ¼ .993, TLI ¼ .991, CFI ¼ .993.

a Statistically significant (p < .001). / Table 10

Standardized path coefficients between perceived service quality on customer-company identification and repurchase intentions and subjective well-being. Predicted relationships Standardized Path loadings T-value Standard error

Perceived Service quality / Customer-company identification .436a 7.825 .062

Perceived Service quality / Repurchase intentions .297a 5.310 .064

Perceived Service quality / Subjective well-being .279a 4.698 .049

Customer-company identification / Repurchase intentions .244a 4.330 .058

Customer-company identification / Subjective well-being .208a 3.476 .044

Goodness-of-fit: c2/df ¼ 1.719, RMSEA ¼ .040, RMR ¼ .032, GFI ¼ .962, AGFI ¼ .945, NFI ¼ .967, RFI ¼ .958, IFI ¼ .986, TLI ¼ .982, CFI ¼ .986.

a Statistically significant (p < .001). Table 11

Direct, indirect, and total effects of service quality on customer-company identification, repurchase intention, and subjective well-being. Predicted relationships Direct effects Indirect effects Total effects

Perceived Service quality / Customer-company identification .436a e .436a

Perceived Service quality / Repurchase intentions .297a .106a .404a

Perceived Service quality / Subjective well-being .279a .094a .369a

Customer-company identification / Repurchase intentions .244a e .244a

Customer-company identification / Subjective well-being .208a e .208a

a Statistically significant (p < .001). Table 12

Mediation role of relationship quality summary. Hypothesis Mediator Relationship Full mediation Partial mediation Not supported H4a Overall customer satisfaction

Perceived service quality / Repurchase intentions √ H4b Overall customer satisfaction

Perceived service quality / Subjective well-being √ H5a

Customer-company identification

Perceived service quality / Repurchase intentions √ H5b

Customer-company identification

Perceived service quality / Subjective well-being √

et al., 1999, 2007; Sirgy et al., 2011), few studies have explored

effects of service quality and customer-company identification on

antecedents to tourists' subjective well-being.

customer loyalty, but has largely ignored the mediating role that

A number of prior studies have investigated the relationships

customer-company identification could play on customer loyalty

between service quality perceptions, customer satisfaction, and

constructs. This study helps to address these noted gaps in the

repurchase intentions. However, the results of these studies have

literature. We provide empirical validation that customers do,

not been consistent. Some studies indicate that customer satisfac-

indeed, identify with hospitality providers (i.e., lodging) and this

tion has a partial mediating role (e.g., Dagger & Sweeney, 2006;

in-turn provides positive consequences for both the service pro-

Walsh & Bartikowski, 2013). The current study found customer

vider (i.e., repurchase intentions) and the customer (i.e., subjective

satisfaction has a full mediating effect of service quality on

well-being). Specifically, we demonstrate that customer-company

repurchase intentions, which is consistent with the recent findings

identification has a partial mediating effect between perceived

of Su et al. (2014) who sampled tourists in a Chinese heritage

service quality and repurchase intentions, as well as subjective

tourism context. Future research will be needed to help clarify if

well-being. These findings suggest that lodging companies can help

these differences are associated with culture, type of industry, or

satisfy an individuals' self-definitional needs even in the absence of other factor(s).

formal membership. By doing so, this study extends prior research

Although there has been previous exploration of the relation-

on the social identity perspective of customer loyalty through

ship between tourism services, satisfaction with tourism experi-

incorporating subjective well-being as a consequence of customer-

ence, and life satisfaction (Neal et al., 1999, 2004, 2007; Sirgy et al., company identification.

2011), one contribution of the current study is the identification of

the full mediating role that satisfaction plays between service

quality and the subjective well-being of Chinese tourists. This

5.2. Managerial implications

finding is not consistent with Dagger and Sweeney (2006) who

found service satisfaction to partially mediate the effect of service

Not surprisingly a key take-a-way from this study is that hos-

quality on quality of life in a health service setting. One explanation

pitality firms need to provide a high level of service quality.

of the differing results may be that tourists are likely to be primarily

Perceived high levels of service quality help to cultivate a satis-

focused on obtaining satisfactory experiences when on holiday,

factory relationship with customers and foster greater customer-

whereas in a health service context, customers will assign a greater

company identification, in turn promoting customer repurchase

importance to the quality of service received.

behavior and improved subjective well-being. In particular, hotel

This study introduces the customer-company identi

managers should make an effort to develop a distinctive, service fication

construct into a tourism/hospitality context. Recently, Martínez and

quality based corporate identity that resonates with their core

Rodriguez del Bosque (2013) pointed out that “despite the recog-

customers. To achieve such an identity, it will be important for

nized importance of customer-company identi

lodging managers to first determine the relative importance of fication, its effects

on the development of hotel customer loyalty remain relatively

various quality dimensions and track these, as well as overall unexplored”

quality, over time to identify trends. The measurement of perceived

(p. 96). Extant literature has focused on the direct

performance on both overall quality and individual quality /

dimensions will be useful to help hotel managers target areas for

commitment, communication quality, conflict) into our model.

improvement at individual properties, as well as providing a means

Future researchers may also want to consider the relationship

to identify performance differences between properties (if man-

ordering between perceived service quality and any investigated

aging multiple lodging locations). In addition, it is important to

proposed relationship quality constructs. For example, although the

assess competitor performance to identify possible quality differ-

perceived service quality to customer-company identification

ences. Relative performance differences on individual quality di-

ordering appears to have substantiation in the literature, this

mensions can then be used as the basis for competitive

relationship is not necessarily straightforward and does not pre- differentiation.

clude the possibility that there may be a reverse relationship.

Given the positive consequences of customer-company identi-

The students participating in the pilot study were pre-screened

fication, tourism/hospitality managers and marketers should

to ensure experience with lodging services. The investigated

consider the level of resources required to incorporate into their

construct scales did demonstrate acceptable levels of reliability in

strategy decisions the elements that drive customer-company

the pilot test and, again, in the actual study with our population of

identification. Service companies may be more likely to benefit

interest, hotel guests. However, to more properly screen scale items

from identification than firms that focus on selling goods since the

for appropriateness, the pretest should have used respondents

inseparability of consumerecompany interactions helps to facili-

more similar to those from the population to be studied. Finally, the

tate customer engagement and, thus, identification (Bhattacharya

data used in this research are cross-sectional in nature, which raises

& Sen, 2003). To build identification, hospitality-based organiza-

concerns about the causal relationships between constructs in the

tions must devise strategies for meaningful customer-company

tested model. Stronger evidence of causality via longitudinal and/or

interactions that embed customers in the organization and make

experimental studies is needed.

them feel like insiders. Rather than focusing only on acquiring new

customers, hospitality managers must emphasize the retention and Acknowledgment

enhancement of customer relationships as a strategic focus.

The process of forging stronger bonds with customers can start

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation

with tracking information about purchases and using that infor-

for Young Scholars of China (No. 71203240), the State Key Program

mation to offer financial incentives. This does not simply mean that

of National Natural Science of China (No. 71431006); the Founda-

the hospitality organization charges lower prices. Rather, this

tion for Innovative Research Groups of the National Natural Science

retention strategy financially rewards customers for more pur-

Foundation of China (No. 71221061), the State Key Program of

chases or relationship longevity via loyalty programs (e.g., frequent

National Natural Science of China (No. 71431006) and Tourism

guest discounts or perks). The next challenge is to combine finan-

Young Expert Training Program (TYEPT201436).

cial incentives with interpersonal bonds between the customer and

the hospitality organization. For example, customers enrolled in a References

loyalty program could be asked to participate in the aforemen-

tioned tracking of quality perceptions for the firm. Interacting as

Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Gruen, T. (2005). Antecedents and consequences

participants in providing feedback and suggestions to the hospi-

of customer-company identification: expanding the role of relationship mar-

tality organization can bring customers face-to-face with hospi-

keting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 574e585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ 0021-9010.90.3.574.

tality service quality, while drawing them closer to the center of

Akbaba, A. (2006). Measuring service quality in the hotel industry: a study in a

hospitality through a coecreation activity. As the partnership de-

business hotel in Turkey. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 25(2),

velops, the relationship advances from merely meeting customers'

170e192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2005.08.006.

Akter, S., D'Ambra, J., Ray, P., & Hani, U. (2013). Modelling the impact of health

basic wants to a situation in which the firm has the ability to

service quality on satisfaction, continuance and quality of life. Behavior and

organize and use information about customers more effectively

Information Technology, 32(12), 1225e1241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/

than competitors. This allows the hospitality provider to strengthen 0144929X.2012.745606.

Albacete-Sa´ez, C. A., Fuentes-Fuentes, M. M., & Llore´ns-Montes, F. J. (2007). Service

customer ties through greater service customization. When cus-

quality measurement in rural accommodation. Annals of Tourism Research,

tomers receive individualized service, the end result should be

34(1), 45e65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.010.

greater satisfaction, greater subjective well-being, and a reduced

Andereck, K. L., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2011). Exploring the nature of tourism and

likelihood of switching to competitors.

quality of life among residents. Journal of Travel Research, 50(4), 248e260.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a

6. Research limitations and future research directions

review and recommend two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3),

411e423. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.103.3.411.

Anderson, E. W., & Sullivan, M. W. (1993). The antecedents and consequences of

The current study tests its hypothesis with domestic Chinese

customer satisfaction for firms. Marketing Science, 12(2), 125e143. http://

hotel customers using a convenience sample. Evidence of model

dx.doi.org/10.1287/mksc.12.2.125.

stability and generalizability can only come from performing the

Arnold, M. J., & Reynolds, K. E. (2003). Hedonic shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing, 79(2), 77

analysis on additional samples in other contexts. Future researchers

e95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(03)00007-1.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization.

should consider examining the investigated relationships utilizing

Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20e39. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/

more generalizable random sampling techniques as well as more AMR.1989.4278999.

geographically and ethnically diverse populations. The model

Athanasopoulou, P. (2009). Relationship quality: a critical literature review and

research agenda. European Journal of Marketing, 43(5/6), 583e610. http://

tested also contained a limited number of constructs. There are a

dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090560910946945.

variety of additional antecedents (e.g., corporate reputation, service

Babin, B. J., Lee, Y., Kim, E., & Griffin, M. (2005). Modeling consumer satisfaction and

fairness) and consequences (e.g., word-of-mouth referrals, price

word-of-mouth: restaurant patronage in Korea. Journal of Services Marketing,

19(3), 133e139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/08876040510596803.

sensitivity) that could be included in future studies to develop a

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in

more comprehensive framework. Relationship quality is a higher

social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical consider-

order construct consisting of several distinct but related compo-

ations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173e1782. http://dx.

doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

nents or dimensions. Future researchers should, therefore, consider

Bejou, D., Wray, B., & Ingram, T. N. (1996). Determinants of relationship quality: an

integrating additional relationship quality constructs (e.g., trust,

artificial neural networks analysis. Journal of Business Research, 36, 137e143.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(95)00100-X. /

Bentler, P. M., & Bonnet, D. C. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the

Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 7e18. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1251898.

analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588e606. http://

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with un-

dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588.

observable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research,

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer-company identification: a frame- 18(1), 39e50.

work for understanding consumers' relationships with companies. Journal of

Getty, J. M., & Getty, R. L. (2003). Lodging quality index (LQI): assessing customers'

Marketing, 67(2), 76e88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609.

perceptions of quality delivery. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: on being the same and different at the same

Management, 15(2), 94e104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09596110310462940.

time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475e482. http://

Gilbert, D., & Abdullah, J. (2004). Holiday taking and the sense of wellbeing. Annals

dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001.

of Tourism Research, 31(1), 103e121.

Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS:

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis.

Basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Associates.

He, H., & Li, Y. (2011). CSR and service brand: the mediating effect of brand iden-

Chang, K. C. (2013). How reputation creates loyalty in the restaurant sector. Inter-

tification and moderating effect of service quality. Journal of Business Ethics,

national Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(4), 1e25. http://dx.

100(4), 673e688. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0703-y.

doi.org/10.1108/09596111311322916.

He, H., Li, Y., & Harris, L. (2012). Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. Journal

Chang, Y. W., & Chang, Y. H. (2010). Does service recovery affect satisfaction and of Business Research, 65(5), 648e657. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

customer loyalty? an empirical study of airline services. Journal of Air Transport j.jbusres.2011.03.007. Management, 16(6), 340e342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., & Gremler, D. D. (2002). Understanding rela- j.jairtraman.2010.05.001.

tionship marketing outcomes: an integration of relational benefits and rela-

Chen, C. F., & Chen, F. S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and

tionship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4(3), 230e247. http://dx.doi.org/

behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29e35. 10.1177/1094670502004003006.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.008.

Hennig-Thurau, T., & Klee, A. (1997). The impact of customer satisfaction and

Chen, C. F., & Tsai, M. H. (2008). Perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty of TV travel

relationship quality on customer retention: a critical reassessment and model

product shopping: involvement as a moderator. Tourism Management, 29(6),

development. Psychology & Marketing, 14(8), 737e764. http://dx.doi.org/

1166e1171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.02.019.

10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199712)14:8<737::AID-MAR2>3.0.CO;2-F.

Chin, W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling.

He, Y., & Song, H. (2009). A mediation model of tourists' repurchase intentions for

In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295e336).

packaged tour services. Journal of Travel Research, 47(3), 317e331. http://

Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

dx.doi.org/10.1177/0047287508321206.

China Travel Guide. (2014). China tourism statistics in 2013: Domestic tourism.

Hobson, J., & Dietrich, U. (1994). Tourism, health and quality of life: challenging the

Retrieved October 19, 2014 http://www.travelchinaguide.com/tourism/.

responsibility of using the traditional tenets of sun, sea, sand, and sex in

Chi, C. G. Q., & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination

tourism marketing. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 3(4), 21e38. http://

image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: an integrated approach.

dx.doi.org/10.1300/J073v03n04_02. Tourism Management, 29(4), 624e636. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

Hong, S. Y., & Yang, S. U. (2009). Effects of reputation, relational satisfaction, and j.tourman.2007.06.007.

customer-company identification on positive word-of-mouth intentions. Jour-

Clarke, T. (2001). Balancing the triple bottom line: financial, social and environ-

nal of Public Relations Research, 21(4), 381e403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/

mental performance. Journal of General Management, 26(4), 16e27. 10627260902966433.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.).

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modeling:

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.