Preview text:

TAKING STOCK MARCH 2023 HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH TAKING STOCK MARCH 2023 HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH @2023 The World Bank

1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20422

Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org

This work is a product of the sta of the World Bank with external contributions. The ndings, interpretations

and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reect the views of the World Bank and its

Board of Executive Directors. The World Bank do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this

work. The boundaries, colors, denominations and other information shown on any map in this work do

not imply any judgement on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the

endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries.

Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and

immunities of the World Bank, all of which are specically reserved.

All queries on rights and licenses should be addressed to the Publishing and Knowledge Division, the World

Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC, 20433, USA, Fax: 202-522-2625; email: pubrights@worldbank.org.

HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................... 8

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................... 9

OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................... 10

Special Topic: Harnessing the potential of the services sector for growth ...............................15

CHAPTER 1. RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS AND PROSPECTS ................................. 18

I. Recent economic developments .......................................................................................................19

II. Economic outlook, risks, and policy implications ......................................................................36

CHAPTER 2. HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH ... 42

I. Introduction............................................................................................................................................43

II. The services sector performance in Vietnam ..............................................................................44

III. A diversied services sector with untapped potential..............................................................47

IV. Benchmarking the services sector along four policy areas .....................................................57

V. Policies to leverage the potential of the services sector .............................................................59

REFERENCES .............................................................................................................................. 62 BOXES

Box 1.1. Impact of select macroeconomic shocks on ination in Vietnam .....................................32

Box 2.1. Vietnam’s export-led growth model: in need of upgrading ..................................................44

Box 2.2. Barriers to services trade ...............................................................................................................55 FIGURES

Figure 1.1. Economic growth in 2022 .........................................................................................................19

Figure 1.2. Real GDP growth by sector ......................................................................................................20

Figure 1.3. Contribution to GDP growth from the demand side .........................................................20

Figure 1.4. GDP growth by sector ...............................................................................................................21

Figure 1.5. Retail sales by sector .................................................................................................................21 5 TAKING STOCK MARCH 2023

Figure 1.6. Manufacturing PMI index ........................................................................................................21

Figure 1.7. Labor market ...............................................................................................................................21

Figure 1.8. Change in formal and informal employment ......................................................................22

Figure 1.9. Average monthly income ..........................................................................................................22

Figure 1.10: Current account balance ........................................................................................................23

Figure 1.11. Financial account balance .....................................................................................................23

Figure 1.12. Merchandise trade ...................................................................................................................24

Figure 1.13. Contribution to total merchandise export growth by market ........................................24

Figure 1.14. Contribution to total merchandise export growth by product .....................................25

Figure 1.15. Trade in services ......................................................................................................................25

Figure 1.16. FDI Commitment by sector ...................................................................................................26

Figure 1.17. FDI commitment by type .......................................................................................................26

Figure 1.18. International reserve accumulation ....................................................................................27

Figure 1.19. Loss in ocial reserves between December 2021 and September 2022 ....................27

Figure 1.20. Average exchange rate ............................................................................................................28

Figure 1.21. Rate of currency depreciation against the US$ (select countries) ...............................28

Figure 1.22. Interbank rates and policy rates...........................................................................................29

Figure 1.23. Loan and deposit......................................................................................................................29

Figure 1.24. VN Index and net buying/selling of foreign investors ....................................................30

Figure 1.25. Contribution to CPI ination ................................................................................................31

Figure 1.26. Ination in December 2022 in select countries ................................................................31

Figure 1.27. Producer price indexes ...........................................................................................................32

Figure 1.28. Merchandise import price indexes ......................................................................................32

Figure B.1. The impulse responses of ination to macroeconomic shocks .....................................33

Figure 1.29. Aggregate scal execution .....................................................................................................35

Figure 1.30. Contribution to total revenue growth by main sources .................................................35

Figure 1.31. Planned and executed public spending 2019-22 .............................................................36

Figure 1.32. Major non-oil taxes collection ..............................................................................................36

Figure 2.1. Vietnam: Contribution to GDP growth from the production side, 2010-19 .................45

Figure 2.2. Vietnam: Share of employment, 1995–2019 ........................................................................45

Figure 2.3. Labor productivity in non-service sectors .........................................................................46

Figure 2.4. Labor productivity in service sectors and manufacturing (for comparison) ..............46

Figure 2.5. Services, value added per worker ..........................................................................................47 6

HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH

Figure 2.6. The employment share in services ........................................................................................47

Figure 2.7. Example of how services dier in their tradability, labor intensity, skill utilization,

and linkage to other sectors .........................................................................................................................48

Figure 2.8. Share of employment in the services sector by skills and tradability ..........................49

Figure 2.9. Employment share in global innovator services ................................................................49

Figure 2.10. Share of global innovator services in total services exports, 2017 ..............................50

Figure 2.11. Average size of services and manufacturing establishments .......................................51

Figure 2.12. Manufacturing and services rms’ productivity (value added per worker) relative to

large rms in select countries .....................................................................................................................52

Figure 2.13. The degree of adoption of sophisticated technologies by services rms .................53

Figure 2.14. Share of services used as domestic inputs for manufacturing, 2018 ..........................54

Figure 2.15. Share of global innovator services used as domestic inputs for manufacturing,

2018 ....................................................................................................................................................................54

Figure 2.16. Number of workers on ve of the largest English-language online freelance

platforms ..........................................................................................................................................................55

Figure B.2.a. Services trade restrictiveness Index (STRI) by country and policy, 2021 ................56

Figure B.2.b. Vietnam’s evolution of services trade restrictiveness, 2014-21 ...................................56

Figure B.2.c. Services STRI, 2014-21 ..........................................................................................................57

Figure B.2.d. Logistics services STRI, 2014-21 .........................................................................................57

Figure 2.17. Benchmarking Vietnam along the 4T dimensions ...........................................................58 TABLES

Table 0.1. Selected economic indicators, Vietnam, 2020-25 ................................................................13

Table 1.1. Selected economic indicators, Vietnam, 2020-25 ................................................................37 7 TAKING STOCK MARCH 2023 ABBREVIATIONS BPO Business Process Outsourcing BSA Banking Supervisory Agency CIF Cost, insurance, freight CPI Consumer Price Index EMDEs

Emerging markets and development economies FAT

Firm-level Adoption of Technology FDI Foreign Direct Investment FOB Free-on-board FTAs Free Trade Agreements GDP Gross Domestic Product GFS Government Finance Statistics GI Greeneld investment GSO General Statistics Oce IMF International Moneytary Fund LMICs Lower middle income countries MOF Ministry of Finance NEER

Norminal eective exchange rate NSA not seasonally adjusted OECD

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development PPI Producer Price Index SBV State Bank of Vietnam SD standard deviation SEDS

Socio-Economic Development Strategy SME Small and medium enterprises STI

Science, technology, and innovation STRI

Services Trade Restrictiveness Index 8

HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This report was written by Dorsati Madani (Senior Country Economist), Elwyn Davies (Senior

Economist), and Hoang The Nguyen (Research Analyst - Consultant). It beneted from

contributions from Dung Viet Do (Senior Country Ocer), Fang Guo (Economist), Thu-Ha

Thi Nguyen (Research Analyst), Judy Yang (Senior Poverty Specialist), Ketut Kusuma (Senior

Financial Sector Specialist), and Viet Quoc Trieu (Senior Financial Sector Specialist). We are

grateful to Arti Grover (Principal Economist) and Andrea Coppola (Lead Economist and EFI

Program Leader) for their comments. We are grateful to Ngan Hong Nguyen (Senior External

Aairs Ocer) and Anh Thi Quynh Le (External Aairs Ocer) for their communication support.

Khanh Linh Thi Le (Program Assistant) provided excellent support during the preparation of the report.

The team is grateful for the overall guidance of Sebastian Eckardt (Practice Manager,

Macroeconomics - Trade and Investment), Asya Akhlaque (Practice Manager, Investment

Climate), and Carolyn Turk (Country Director for Vietnam). 9 OVERVIEW

HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH

Heightened uncertainties continue to growth, mostly due to the strong performance

weigh on the prospects of the global of exports in the rst three quarters of the year. economy

Employment and labor income recovered to

In 2022, the global economy continued to

pre-COVID-19 levels in 2022, contributing to

grapple with low growth, high inflation, the poverty reduction. Employment recovered to

lingering effects of COVID-19, and the war pre-COVID-19 levels (50.6 million) and labor

in Ukraine. The global economy registered incomes in 2022 (VND 6.2 million average real

a weak (2.9 percent) expansion in 2022, monthly income) surpassed 2019 numbers,

with the U.S. and the euro area registering while

labor participation reached 68.5

1.9 percent and 3.3 percent GDP growth, percent of total population, an increase of 1.2

respectively. Global economic headwinds are percentage points compared to Q4-2021, still

expected to continue, and growth is projected below the pre-COVID-19 rate of 71.1 percent.

to decelerate to 1.7 percent in 2023, the third These improvements in the labor market

weakest pace in nearly three decades.1 This contributed to the poverty rate declining from

reflects simultaneous policy tightening to an estimated 3.6 percent in 2021 to a projected

contain high inflation, worsening financial 3.3 percent in 2022.2

conditions, and continued effects of of the However, weaker global demand led to war in Ukraine.

renewed labor market pressures in Q4-

2022. The economic slowdown in U.S. and

Vietnam’s economy rebounded strongly European markets led to slowing orders and in 2022

exports in Q4-2022, with a reported impact on

Vietnam’s GDP grew by 8.0 percent (y/y) in employment in major export manufacturing

2022, above its average rate of 7.1 percent in centers such as the Ho Chi Minh City area. The

2016-2019. The strong growth was partly due to underemployment rate rose (from 1.92 to 1.98

the low base eect, driven by a rebound of the percent) among working-age persons, and the

domestic private consumption post-COVID-19 share of workers with informal employment

and solid performance of export-oriented increased from 65.0 in Q3-2022 to 65.4 in Q4-

manufacturing in the rst nine months 2022.

of the year. Overall, private consumption

contributed about 4.3 percentage points to The balance of payment showed signs

growth in 2022, compared to the 1.1 percentage

of weakening in 2022

point contribution in 2021, and in line with

The current account registered a deficit of

contributions in the pre-COVID-19 period. The US$4.9 billion in the first nine months of 2022

contribution of the public sector to growth

and is expected to remain in deficit in 2022,

remained limited (one percentage points), the second year in a row. While the goods trade

given the implementation challenges in public balance registered US$6.7 billion in surplus in the

investment and continued eorts by the first three quarters of 2022, exports contracted

authorities to reduce current expenditures. Net by 9 percent (y/y) in November and 14 percent

exports contributed 2.7 percentage points to (y/y) in December 2022 due to weakening 1

World Bank. Global Economic Prospects, January 2023. 2

As measured by the World Bank’s lower middle-income country poverty line US$3.65/day 2017 PPP. 11 TAKING STOCK MARCH 2023

demand from the U.S. and EU. Services trade demand with private consumption accelerating

balance remained in deficit (-US$6.9 billions) from 6.5 percent y/y in H1-2022 to 9.5 percent

as service exports have not fully recovered y/y in H2, or around 2 percent (y/y) above trend.

from the pandemic. While FDI disbursements

reached US$15.4 billion by the end of the third Vietnam’s financial sector experienced

quarter, the financial balance surplus narrowed increased pressure in 2022

to US$7.5 billion in Q3-2022 compared to a A combination of external and domestic

US$26.4 billion surplus in Q3-2021. The third factors contributed to heightened

quarter deterioration was mostly connected to uncertainty and volatility in the nancial

short-term capital outflows (estimated at US$8 sector. Global ination and interest-rate

billion) resulting from the impact of monetary increases in the U.S. and other countries had an

tightening in the United States.

impact on the monetary policy stance. Higher

To help stave o pressure on the exchange domestic interest rates (200 bps increase in

rate, the SBV responded with a combination policy rates), raised banks’ cost of fund (180-

of FX interventions, some depreciation, 220 bps increase in 12-month deposits) and, in

and monetary tightening. FX interventions turn, the borrowing cost for individuals and the

led to the sales of an estimated US$22 billion corporate sector. The brief run on the Saigon

in foreign reserves, leaving the reserves at Commercial Bank (SCB) in October 2022,

an estimated US$88 billion (or about three triggered by the arrest of several individuals

months’ import equivalent) by September accused of fraud in real-estate and corporate

2022. To avoid further depletion of reserves, bond deals associated with the bank, shook

the SBV also introduced measures for greater condence in the banking sector and capital

exchange rate exibility, allowing the reference markets. Risk perception increased, and

rate to depreciate by 3.4 percent y/y (albeit investors sought higher yields for domestic

much less than comparator countries). It also investment across the board, including equity

tightened monetary policy with a 200-bps prices (prices dropped by 32.8 percent in 2022),

hike in discount and renancing rates from 2.5 bonds (government bond yields increased by

percent to 4.5 percent and from 4.0 percent to 324 basis points (bps) on average in 2022’), and 6.0 percent, respectively.

bank deposits. Small banks appeared to suer

disproportionately from tightening liquidity,

Following the commodity-price shock of as there was a ight-to-quality amidst this

March 2022, Consumer Price Index (CPI) safety concern. While the authorities took

inflation increased from 1.8 percent in swift action to address nancial markets,

December 2021 to 4.5 percent in December the events underscore deep-seated nancial

2022, breaching the 4 percent policy target. sector vulnerabilities, including weakness in

The inflation was driven mainly by supply side supervision and corporate governance.

factors, particularly during the first half of the

year. Global oil prices led to 21.4 percent y/y Intended expansionary fiscal policy was

higher transport costs by June and contributed thwarted by budget implementation

60 percent of the CPI in the same month, challenges

subsequently passing through to domestic

prices of products. Inflationary pressures were While the government planned for a scal

compounded by the recovery of domestic decit of 4.2 percent of GDP, the budget 12

HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH

registered monthly surpluses during most The near-term outlook remains

of 2022, culminating in an estimated overall favorable but subject to risks

scal surplus of 1.4 percent of GDP. The

surplus was partly driven by the higher-than-

Reflecting domestic and external headwinds,

planned collection of revenues (+26.4%). While GDP is expected to grow by 6.3 percent in

planned revenues were set at 14.5 percent of 2023. While the tourism sector continues to

GDP, collections reached an estimated 18.9 recover, services-sector growth will moderate

percent of GDP. Slow procurement and issues

as the post-COVID-19 low base-effects fade.

associated with land acquisition led to the Domestic demand is expected to be affected by

under-execution of public investments, which higher estimated inflation (4.5 percent average)

also contributed to the scal surplus. Capital in 2023, which may erode household purchasing

expenditures were also aected by lengthy power. Rising interest rates may weigh on

timelines for preparation of new projects and private investment. Amid softer external

rigid contract management (including revisions demand, contribution of net exports to growth is

in design and cost of ongoing projects). While estimated to be negative (-0.6 percentage points).

planned expenditures were set at 18.8 percent The economy is expected to benefit from the

of GDP for the year, execution is estimated partial roll out of the investment component

at 17.5 percent of GDP. As a result of scal of the recently adopted government support

surplus and high growth, debt is estimated to program (about 1.6 percent of GDP). The current

have fallen from 39.3 percent of GDP in 2021 account is expected to register a 0.1 percent of

to 35.7 percent of GDP in 2022, signicantly GDP surplus in the medium-term, thanks to the

below the 60 percent debt-to-GDP threshold recovery of goods export performance, return of set by the National Assembly.

foreign tourism, and resilient remittances.

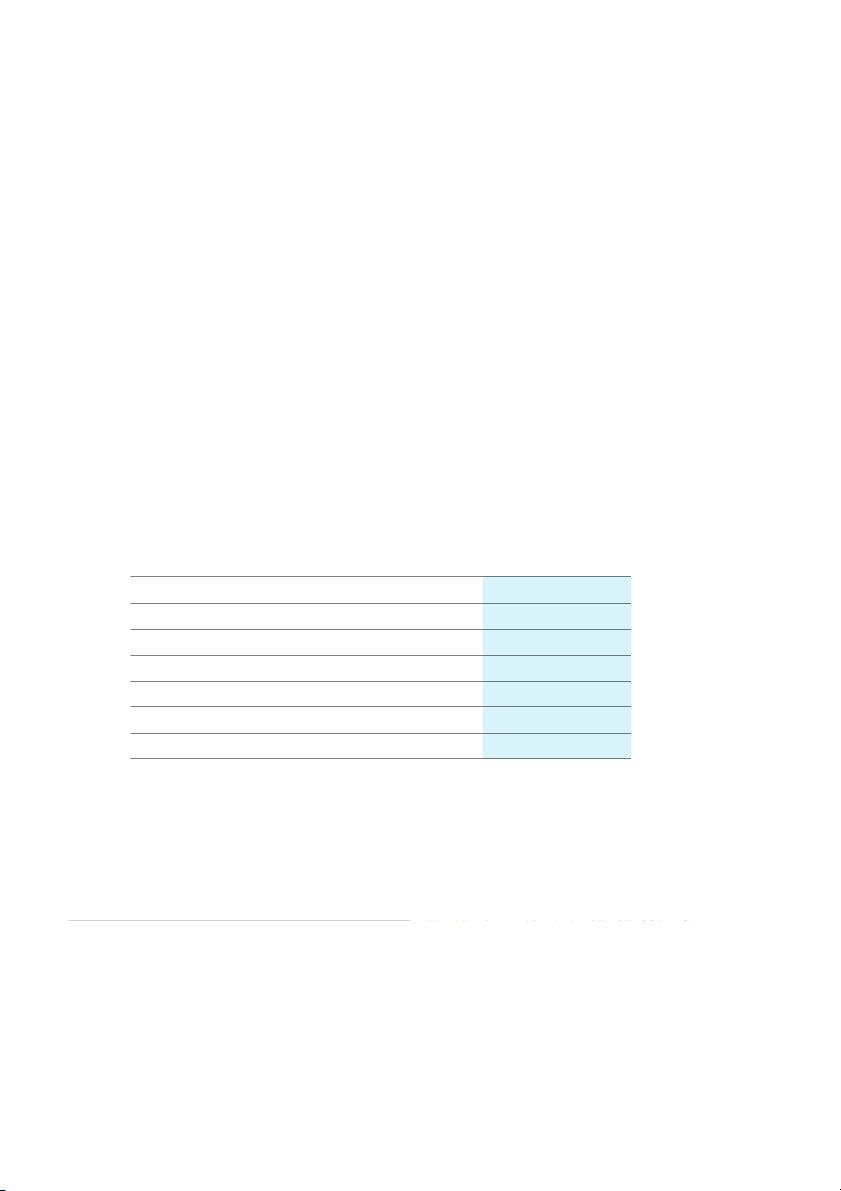

Table 0.1. Selected economic indicators, Vietnam, 2020-25 Indicator 2020 2021e 2022e 2023f 2024f 2025f GDP growth (%) 2.9 2.6 8.0 6.3 6.5 6.5

Consumer Price Index (average, %) 3.2 1.8 3.1 4.5 3.5 3.0

Current account balance (% of GDP) 4.3 -1.0 -1.7 -0.3 0.1 0.1 Fiscal balance (% of GDP) -2.9 -3.4 1.4 -0.3 0.8 1.4 Public debt (% of GDP): MOF a/ 43.7 42.7 38.0 39.0 --- --- Public debt (% of GDP): GFS b/ 41.3 39.3 35.7 35.0 33.2 31.0

Source: GSO, MOF, SBV, IMF, and World Bank sta calculations

Note: The revised GDP is used in all calculations unless otherwise stated. e = estimate; f = forecast. a/ As reported by the MOF b/ Following GFS 13 TAKING STOCK MARCH 2023

Risks to the outlook are broadly balanced. inflation, financial stability, and growth

On the downside, weaker than expected objectives. While rate hikes were necessary to

growth in Vietnam’s major export markets contain inflation and exchange rate pressures,

– the U.S., China, and the eurozone- could ensuring adequate liquidity is crucial to ensuring

aect export prospects. Persistent ination in the proper functioning of key funding markets

the US and the eurozone could lead to tighter in the context of heightened risk sentiment.

nancial conditions, aecting Vietnam’s Externally, further monetary tightening in the

nancial sector. Geopolitical tensions and U.S. and other advanced economies could

risks also remain high potentially aecting induce further capital outflows from Vietnam

investor sentiments in the short to medium and create pressure on the exchange rate. In

run. Domestically, persistent price increases such a case, increased exchange rate flexibility

could cause ination expectations to rise, could help accommodate external pressures.

feeding into destabilizing pressures on nominal Strengthened policy and supervisory

wages and production costs and aecting frameworks in the nancial sector will help

domestic demand. Weaknesses in the policy address emerging nancial risks. Six areas of

and supervisory framework of the nancial reform stand out. First, enhance the framework

sector and the balance sheets in the corporate,

for risk-based supervision by the SBV. Second, banking and household sectors

could strengthen the framework for resolving weak

amplify risks, aecting domestic investor or insolvent banks. Third, establish strong

and consumer sentiment. Implementation frameworks and policies for supervising

challenges could also hamper the execution consolidated banking groups, including a

of the planned public investment program. clear separation between banks and company

On the upside, improved growth prospects groups. Fourth, amend the Law on Credit

in China, the US, or EU and stronger than Institutions and the State Bank Law to ensure

expected global demand could lift exports and supervisors have a robust legal mandate while

hence growth above the baseline projection.

discharging their duties in good faith. Fifth,

Domestic and external headwinds enhance corporate bond market standards,

warrant coordinated and data-driven including promoting a more-transparent public

policy responses from the authorities

oer market (vis-à-vis private placement) and

using credit ratings to strengthen investor

A supportive fiscal policy stance could hedge protection and prevent market abuse. Sixth,

against downside-risks to growth. Vietnam increase the overall transparency of the

has fiscal space to act and in the short run and the nancial sector by regularly publishing

focus is appropriately on the implementation banking sector and nancial market indicators

of the capital budget, including the projects promptly with sucient granularity. The lack

identified in the Recovery and Development of transparency of the banking sector data and

policy package program that prioritize digital information might have contributed to market and physical infrastructure.

uncertainties and volatility. Many of these

An agile monetary policy—closely coordinated long standing reforms would benet from a

with fiscal policy objectives—would help proactive government approach as they take

to keep domestic inflation under control. time to complete and may require changes

in legal foundations and culture within and

Following last year’s tightening measures,

monetary policy will need to continue balancing among regulatory/supervisory authorities. 14

HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH

SPECIAL TOPIC: HARNESSING THE

POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH

The services sector has been a critical However, the performance of Vietnam’s

contributor to economic growth in services sector lags peer countries.

Vietnam but its performance lags Productivity and employment in the services comparators

sector in Vietnam remain lower than many

regional, structural, and aspirational peers.

The services sector has been the economy’s For example, Vietnam’s services sector labor

largest sector for the past decade. The productivity (measured by value added

services sector grew from 40.7 percent of per worker) has increased by 34.3 percent

GDP in 2010 to 44.6 percent of GDP in 2019. between 2011-19. However, at US$5,000

Moreover, as Vietnam’s economic structural (constant dollar) per worker in 2019, it is still

transformation progressed, the share of

well below comparators, including Malaysia

workers employed in services increased (US$20,900), the Philippines (US$9,300),

from 19 percent in 1991 to 35.3 percent in and Indonesia (US$7,300). Exports of high-

2019, absorbing a large share of workers

skilled, knowledge-rich services (called global

leaving the agriculture sector and making innovator services) only constitute 9 percent

the services sector the second largest source of total services exports. Only 6.4 percent of

of jobs in the country, after agriculture.

total employment in the services sector is in

Looking ahead, services could play a this sub-sector, including ICT, nance and

crucial role in supporting Vietnam to sustain professional services which are usually among

productivity growth and achieve its ambition the most productive in the economy.

to become a high-income economy by Small scale of rms, restrictions to services

2045. All high-income economies boast large trade, low technological adoption and few

services sectors as the most signicant source inter-sectoral linkages aect productivity.

of job creation and the generation of economic Vietnam’s services sector is dominated by

value. For example, in 2019, services (by value-

small scale rms, employing an average of

added) constituted 70.8 percent of the GDP in only 1.5 workers. This rm scale is about half

Singapore and 57.2 percent in the Republic of the size of what is expected based on its level

Korea. Employment in services constituted 84 of GDP. Also, the 2021 OECD’s Services Trade

percent and 70 percent of total employment Restrictiveness Index (STRI) for Vietnam is

in Singapore and Korea, respectively. Services relatively high compared to most aspirational

could also play an essential role in upgrading peers (Singapore, South Korea, Malaysia),

Vietnam’s development model by increasing mostly due to restrictions on foreign entry

value addition in the other sectors of the for service delivery. In addition, According to economy.

the Firm-level Adoption of Technology (FAT) 15 TAKING STOCK MARCH 2023

survey, both average and frontier services R&D-based innovation and the government

rms in Vietnam are far from the global frontier has tried to ‘push the technological frontier”

in terms of technology adoption. Finally, by supporting university and research

Vietnamese manufacturing rms are relatively institutions over domestic rms. These

limited in their use of services—the value of policies have a limited focus on non-R&D-

services as domestic inputs is only 14 percent based forms of innovation, such as technology

with a mere 1.6 percent of manufacturing adoption (Akhlaque, Cirera & Frias 2020).

rms using global innovator services (ICT, Going forward, it would be useful to further

professional, and nancial services).

investigate questions such as: (i) how should

STI policies and funding bias towards R&D

Unlocking the services sector’s potential be rebalanced to focus more on upgrading

rm capabilities through business technology

Based on the preliminary analysis presented adoption and diusion? (ii) which policy

in this special focus section, the following instruments could support further knowledge

broad policy directions can be identied. and technology transfers to small and medium First, Vietnam could further

reduce enterprises (SME)? (iii) what are the policy

restrictions to services trade and foreign and funding instruments that could support a

investment. OECD’s STRIs indicate that certain larger number of rms engaging in incremental “backbone” services

sectors—including innovation of products and processes and

telecommunications, logistics, aviation, legal adoption of existing technologies?

services, banking, and insurance—still face

high restrictions and that little progress has Third, focus should be on strengthening

been made in removing or mitigating them in workers skills (especially basic digital skills)

recent years. For instance, foreign investment and the capabilities of rms and managers.

in freight transport is restricted in various Going forward, it would be useful to further

ways, including in internal waterways freight investigate questions such as (i) how can policy

and road freight (FDI up to 49 percent and makers support an upgrade of managerial

51 percent ownership, respectively). Going skills and practices; who will drive this reform

forward, the authorities may wish to consider agenda and who will provide resources for such

(i) reducing restrictions to FDI as innovation training? (ii) how to incentivize partnership

and technology adoption relies on access to between universities and private sector rms

knowledge and to the networks, people, goods, to enhance training; and who would shoulder

and services that disseminate that knowledge the costs of such training programs?

globally; and (ii) undertaking business Lastly, Vietnam should leverage services to

environment reforms to enhance competition promote further growth of other sectors,

and access to nance for domestic rms.

especially manufacturing. For example,

Second, Vietnam should encourage further digital services play a prominent role in

adoption of digital technologies within rms bringing new technologies and innovations

to spur innovation. A recent assessment of to manufacturing, where currently, only a

Vietnam’s science, technology, and innovation minuscule number of rms use “Industry 4.0”

(STI) policies by the World Bank indicates that digital technologies (Cirera et al. 2020).

great focus has been on promoting foreign 16 CHAPTER 1. RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS AND PROSPECTS

HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL OF THE SERVICES SECTOR FOR GROWTH

I. RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS

Heightened uncertainties weighed on the global economy in 2022, as it grappled with low

growth and high ination, the lingering eects of COVID-19, and the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Despite these challenges, the global economy registered a weak (2.9 percent) expansion, with the

U.S. and the euro area registering 1.9 percent and 3.3 percent GDP growth, respectively (Figure

1.1). On the other hand, Vietnam (8 %) and some other East Asian economies (such as Malaysia

and the Philippines) registered strong economic performances, well above advanced economies

(2.5 percent), EMDEs (3.4 percent) and China (2.7 percent).

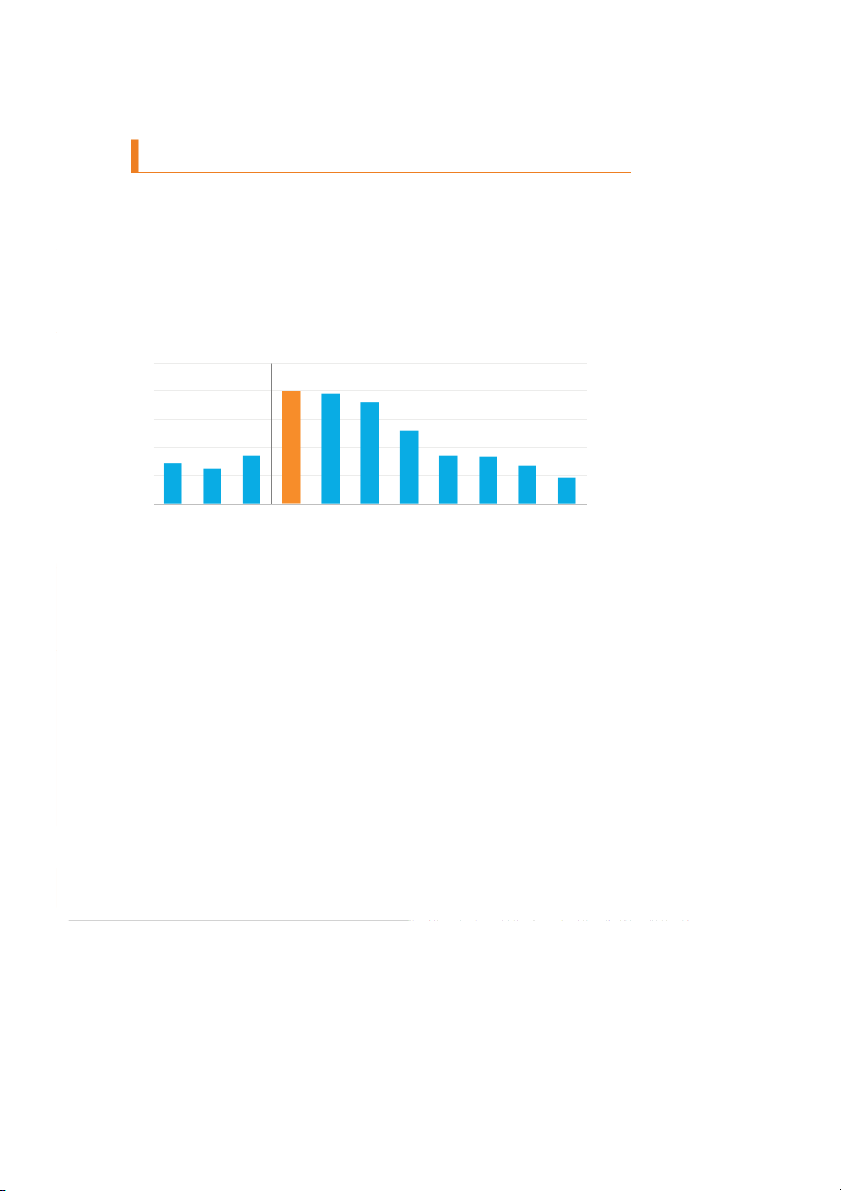

Figure 1.1. Economic growth in 2022 (Percent) 10 8.0 7.8 7.2 8 5.2 6 3.4 3.4 3.3 4 2.9 2.5 2.7 1.9 2 0 d s s d a s rld e E m a sia e sia rea o c D e in te n tn y in A h ta W a M p n ailan v E ie la C a o h ro S d V d T u d A M ilip In E h ite P n U Source: Haver analytics

A strong economic rebound in 2022—partly due to low base effects—with signs of weakening by year-end

Despite the uncertain global environment, Vietnam’s economy grew by 8 percent in 2022—its

highest rate in the past decade. The rebound in growth was partly due to the low base effects

after a significant COVID-19-related slowdown in 2021. Retail sales expanded by 17.1 percent and

the service sector recorded 10 percent growth, driven by private demand (Figure 1.2). In addition,

fueled by external demand, manufacturing exports grew by 8.1 percent (the overall industrial

sector grew by 7.8 percent) and supported the recovery, particularly during the first three quarters

of the year. The agricultural sector continued to perform on trend, growing by 3.4 percent in 2022.

While the overall annual growth was strong in 2022, services and manufacturing sectors

showed signs of slowing down in the fourth quarter (Figure 1.4). The services sector slowed

from a peak of 19.3 percent y/y growth in Q3-2022 to 8.1 percent growth in Q4-2022, mostly due 19 TAKING STOCK MARCH 2023

to base eect. Manufacturing exports started slowing in Q4-2022 in response to weaker demand

from U.S. and the euro area economies. Vietnam’s Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index

(PMI)3 trended down from 52.5 in September to 46.4 in December, signaling three months of

contraction in the manufacturing sector (Figure 1.6).

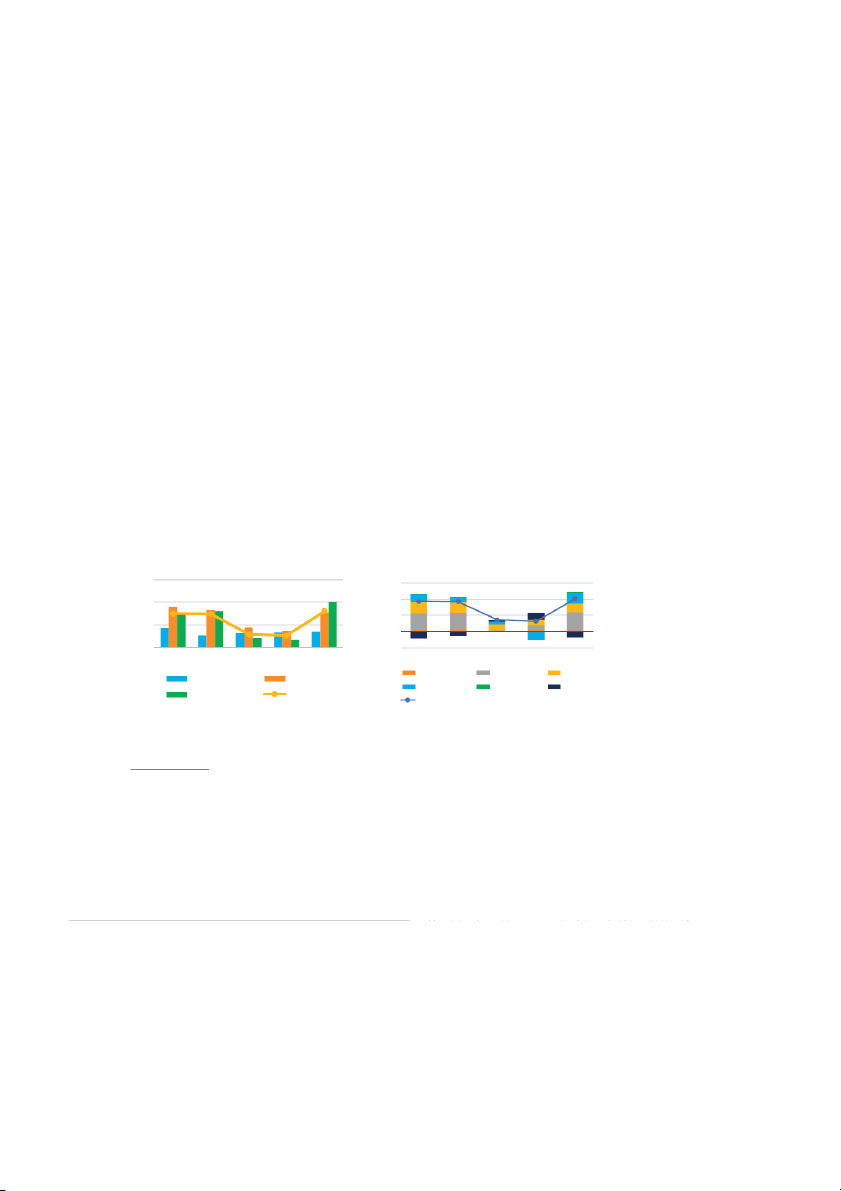

On the demand side, 2022 GDP growth was driven by strong private consumption, a solid

contribution of net exports and investment, and a limited contribution by the public

sector. Overall, private consumption contributed about 4.3 percentage points to growth in 2022,

compared to the 1.1 percentage point contribution in 2021, and in line with contributions in the

pre-COVID-19 period (Figure 1.3). This contribution was evident in the rst three quarters of 2022,

when private consumption of goods and services recovered from the low base eect experienced

during COVID-19 restrictions (Figure 1.5). Net exports contributed 2.7 percentage points to

growth, primarily due to the strong performance of exports in the rst three quarters of the year.

The positive contribution of the net exports is due to the fact that while exports and imports

growth moderated from 18.9 percent and 26.1 percent, respectively, in 2021 to 10.4 percent and

8.4 percent, respectively in 2022, imports decelerated more sharply than exports. Investment

contributed two percentage points to economic growth. Given the slow disbursement of public

investment, private domestic and foreign direct investment (FDI) constituted the main drivers of

gross capital formation, with 2022 FDI disbursement reaching over US$22.4 billion, compared to

US$19.7 billion in 2021 and the highest amount since 2018. Overall, public sector contribution

to growth was limited, given the implementation challenges in public investment and continued

eorts by the authorities to reduce current expenditures (see discussion below).

Figure 1.2. Real GDP growth by sector

Figure 1.3. Contribution to GDP growth from (Percent, y/y) the demand side

(Percentage point, y/y, NSA) 15 12 10 8 4 5 0 0 -4 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 CS: Public CS: Private Investment Agriculture Industry Net exports Inventory Stat. Services GDP GDP

Source: GSO and World Bank sta calculations

Source: GSO and World Bank sta calculations

Note: Industry includes construction

Note: ‘CS’ is consumption; ‘Stat’ is statistical error 3

The S&P Global Vietnam Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index measures the performance of the manufacturing

sector and is derived from a survey of 400 manufacturing companies. The Index is based on ve individual indexes

with the following weights: New Orders (30 percent), Output (25 percent), Employment (20 percent), Suppliers’

Delivery Times (15 percent) and Stock of Items Purchased (10 percent), with the Delivery Times Index inverted so

that it moves in a comparable direction. A reading above 50 indicates an expansion of the manufacturing sector

compared to the previous month, below 50 represents a contraction, while 50 indicates no change. 20