Preview text:

A Novel Acoustic Reflection Principle for

Developing Tactile Sensors Integrated with Catheters for Cardiac Ablation Ly Hoang Hiep* Mac Thi Thoa

School of Mechanical Engineering (HUST)

School of Mechanical Engineering (HUST) Hanoi, Vietnam Hanoi, Vietnam hiep.lyhoang@hust.edu.vn thoa.macthi@hust.edu.vn

Abstract—Cardiac ablation is a commonly employed procedure

Cardiac ablation is a minimally invasive procedure in which

for treating arrhythmias, but the absence of tactile feedback

a long, thin catheter is inserted into the left or right cardiac

increases the risk of tissue trauma. To address this challenge,

chamber through the femoral vein, as shown in Fig. 1. The

integrating tactile sensors with catheters allows for safer opera-

catheter tip includes electrodes utilized to locate abnormal

tions. However, cardiac catheterization necessitates a miniature

tactile sensor with appropriate surgical properties. In this study,

tissue on the heart wall (the cause of AF) for the ablation

a novel acoustic reflection principle for developing a miniature

process. The identified ablation points are then removed using

tactile sensor is proposed to be integrated with sensorized

radiofrequency (RF) energy generated from the catheter tip,

catheters in cardiac ablation procedures. The principle involves

helping to restore normal heart rhythm [8]–[12]. Cardiac

utilizing a sinusoidal acoustic wave within an acoustic cavity

comprising rigid and elastic components. When force is applied,

the acoustic wave interacts with the elastic component, resulting

in a measurable change in the reflected wave. Theoretical analyses

were conducted to evaluate the acoustic wave’s response to

variations in the size of the sound tube. The analysis results

aided in selecting an appropriate sound frequency for the tactile

sensor’s design. A prototype sensor was developed based on

this principle, featuring a sensor tip with an acoustic cavity,

a silicone tube, and an acoustic housing containing a speaker

and a microphone. Experimental results demonstrated a direct

relationship between the sensor output and the applied force.

With a diameter of 3 mm, the developed sensor exhibits clinical

applicability and can measure contact force within the range of 0-

1 N, making it a promising tool to minimize faulty pathways and

reduce heart tissue damage during cardiac ablation procedures.

Index Terms—Cardiac ablation, tactile sensor, acoustic reflec-

tion principle, minimally invasive surgery I. INTRODUCTION

Cardiac Arrhythmia (CA) is characterized by irregular heart-

beats, which can be too fast or too slow, affecting the blood Fig. 1. Cardiac Ablation.

pressure. Some types of CA typically do not significantly

threaten human health. However, other forms of CA can lead

ablation offers many benefits to patients, such as less pain,

to serious heart-related conditions in patients, such as stroke,

quick recovery, and better domestic healing, compared to

vitium cordis, and even sudden cardiac death [1], [2]. Atrial

traditional open surgery, [12]–[14]. However, this procedure

fibrillation (AF) is the most common CA, affecting millions

still presents some challenges that need to be addressed. One

of people and showing an increasing trend yearly [3]–[7]. The

major challenge of cardiac ablation is the precise positioning

use of medications is a common treatment method to manage

of the catheter because doctors lack visual information during

the ablation process [15]. Therefore, the success of the surgery

AF. However, this approach is usually suitable for mild cases,

relies heavily on the surgeon’s skills and the accuracy of the

while severe cases may require surgical or interventional

contact between the catheter tip and cardiac tissue [16].

procedures. Cardiac ablation is a popular procedure for AF

The use of image technologies is a common approach

management recently [8]–[10].

to increase the accuracy of the catheterization procedure.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a widely used method * Corresponding author

for real-time tracking of the catheter tip’s position during the

using the acoustic reflection principle will be developed, and

operation [17]–[20]. This method provides highly accurate

an experiment will be conducted to evaluate the responses of

images; however, the electromagnetic waves from MRI can the sensor’s output.

interfere with the catheter’s signals. Using computed tomog-

raphy (CT) is an alternative option for guiding the catheter II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

tip. However, radiation in this method can adversely affect

A. Acoustic reflection principle

both the patient and the doctor, so it is not commonly used

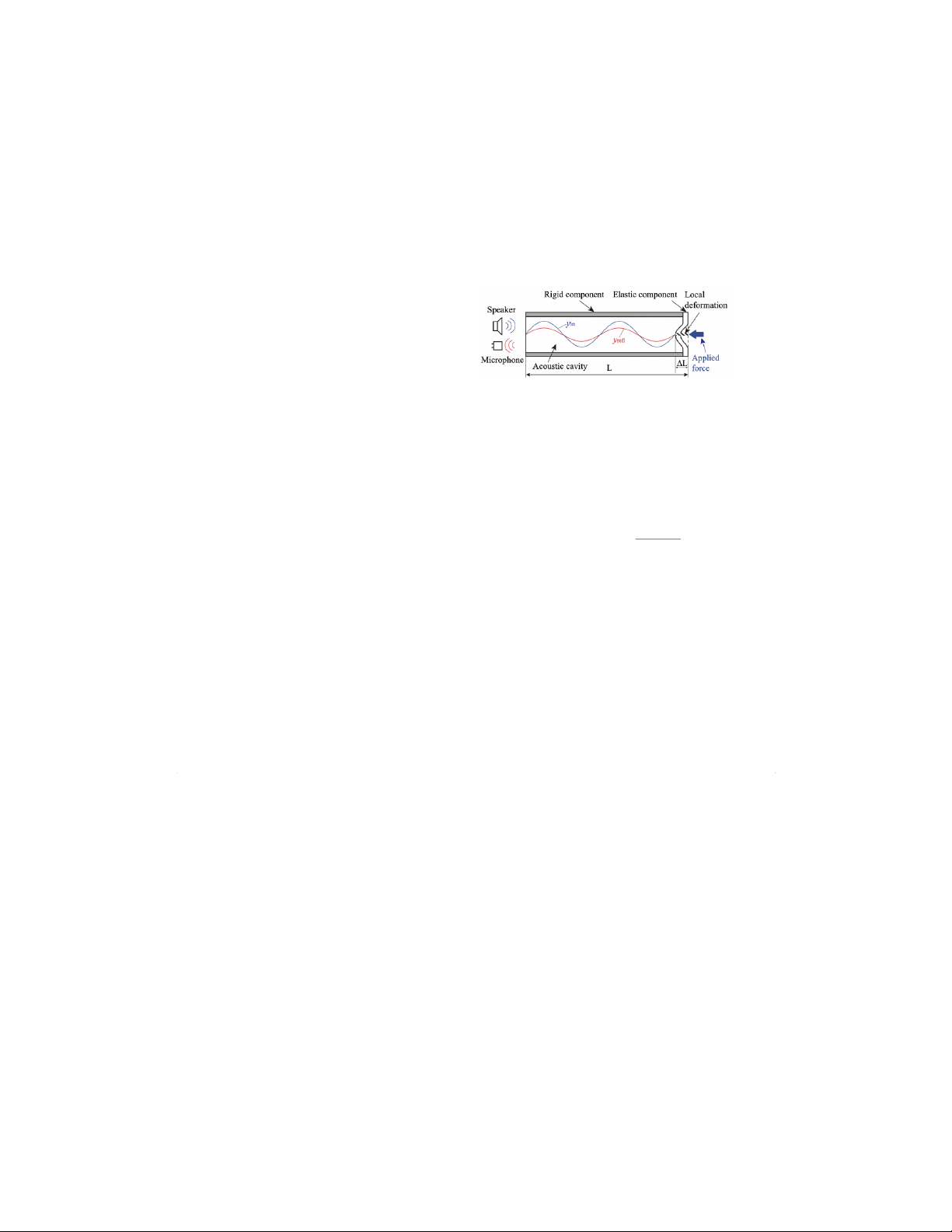

1) Principle: Fig. 2 illustrates an acoustic reflection princi-

[21]. Additionally, Intracardiac Echocardiography (ICE) and

ple that is used to develop a tactile sensor for cardiac ablation.

X-ray fluoroscopy [22], [23] are two techniques also used in

In this principle, a single-frequency acoustic wave generated

cardiac catheterization. Although these image technologies can

by a speaker is inserted into an acoustic cavity. The acoustic

provide relatively accurate information about the catheter tip’s

cavity comprises a rigid component and an elastic component.

position, the force contact information with these techniques

The elastic component covers the distal end of the acoustic is limited.

cavity. The acoustic wave propagates into the acoustic cavity

The force/tactile information plays a crucial role in ensuring

and reflects at the distal end (elastic component). When a force

the quality of ablation [24]–[32]. With adequate contact force

is applied to the elastic components, local deformation occurs,

between the heart tissue and the catheter, RF energy can be

leading to the distortion of the acoustic wave. A microphone

delivered more effectively, leading to a more successful abla-

can continuously capture the acoustic wave within the cavity.

tion process [15]. Furthermore, The force/tactile information

The applied force on the elastic components can be measured

also helps ensure safety by avoiding damage to the heart or

by analyzing the collected acoustic wave.

blood vessels due to excessive force from the catheter tip [33].

Some force and tactile sensors have been developed for

cardiac catheters based on piezoresistive [14], [34]–[38], mag-

netic [39], piezoelectric [40]–[42], and capacitive technologies

[43]. While these sensors can provide highly accurate force

information, the electrical components of sensors located at

the catheter tip area can pose a risk to the patient’s heart

if they leak current. Furthermore, the sterilization capability

of these sensor types remains a challenge when considering

practical usage. Fiber-optic-based force/tactile sensors [19],

[44] can address these challenges because they lack electrical

Fig. 2. Acoustic reflection principle.

components at the sensor tip. Therefore, these sensors do not

have a risk of electrical leakage to the patient and can be

In the acoustic principle depicted in Fig. 2, assuming we

effectively sterilized. However, the manufacturing cost of such

have an input wave (yin) inserted into the cavity with a sensors is relatively high.

frequency of fin and an amplitude of Ain, with a phase angle

In previous research, Tanaka et al. proposed an acoustic

of 0, and its time-domain waveform represented as follows,

reflection principle for the development of tactile sensors in

minimally invasive surgery [45]. Contact force could be deter- yin =Ainsin(2πfint)(1)

mined using acoustic wave estimation. Tactile sensors devel-

The sound wave will reflect at the elastic component, and

oped based on this principle do not have electrical components

the reflection wave yref can be expressed by the following

at the sensor tip, offering advantages such as electrical safety equation,

for human tissue and sterilizability. Additionally, acoustic-

based sensors can be fabricated at a lower cost. Several tactile

yref =rAinsin(2πfin(t−2(L−∆L) v)(2)

sensors for tumor detection and tissue softness measurement

in minimally invasive surgery (MIS) were developed based

where Lis the length of the acoustic tube, ∆Lis the height

on the acoustic principle [45]–[48]. However, in the proposed

of the local deformation, vis the speed of sound in the air

acoustic principle, the sensing area is not located at the distal

340m/s, and r(0 ≤r≤1) is the absorption coefficient of the

end of the acoustic cavity. Designing the sensing components sound wave in the cavity.

at the sensor tip is challenging, which poses a difficulty in

The output wave measured by the microphone yout is

developing small tactile sensors for cardiac catheterization.

the superposition of the input wave and the reflection wave

In this study, a novel acoustic reflection principle is pro-

according to the following equation,

posed for developing a tactile sensor for cardiac ablation. With

this principle, the sensing component will be located at the yout =yin +yref (3)

tip of the tactile sensor, allowing for a significant reduction

Assuming the formula for yout in the time domain is repre-

in the sensor’s size to make it suitable for catheterization. A sented as follows,

preliminary investigation will be conducted to assess the pro-

posed principle. A tactile sensor prototype for cardiac ablation yout =Aoutsin(2πfint+ Φ) (4)

Where Aout is the amplitude of the output wave, and Φis the

phase angle of the output wave. Aout is calculated based on

equations (1), (2), (3), and (4) as follows, A

in(r2+ 1 + 2rcos 4πfin(L−∆L) 2out =A2 v)(5)

In the principle, obtaining information about the amplitude

will be more convenient for signal processing. Therefore, only

the amplitude Aout is considered in this study to estimate the applied force.

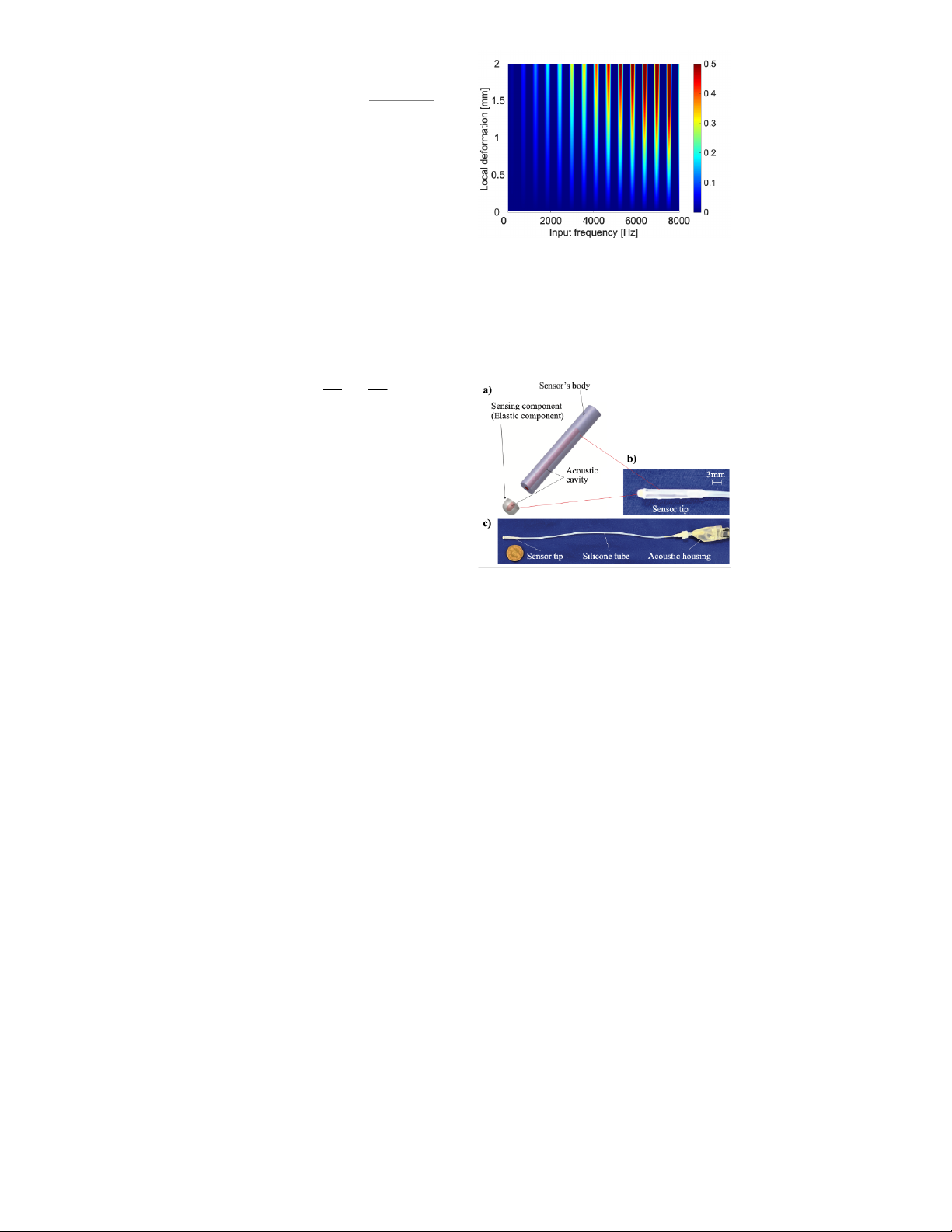

2) Preliminary analysis: The change in the sensor output

signal will be influenced by the parameters in Eq. (5). How-

ever, some parameters will remain fixed and constrained within

a certain range due to the characteristics of the sensor. Here,

the length Lof the acoustic cavity will be fixed for each

sensor, the speed of sound in air will remain constant at v=

340 m/s, and the absorption coefficient rwill be determined

depending on the material and design of the sensor. The height

Fig. 3. Preliminary analysis of the acoustic reflection principle.

of local deformation will vary depending on the interaction

force on the elastic component, but it will also be limited due

to the small size requirement of the sensor. In this analysis,

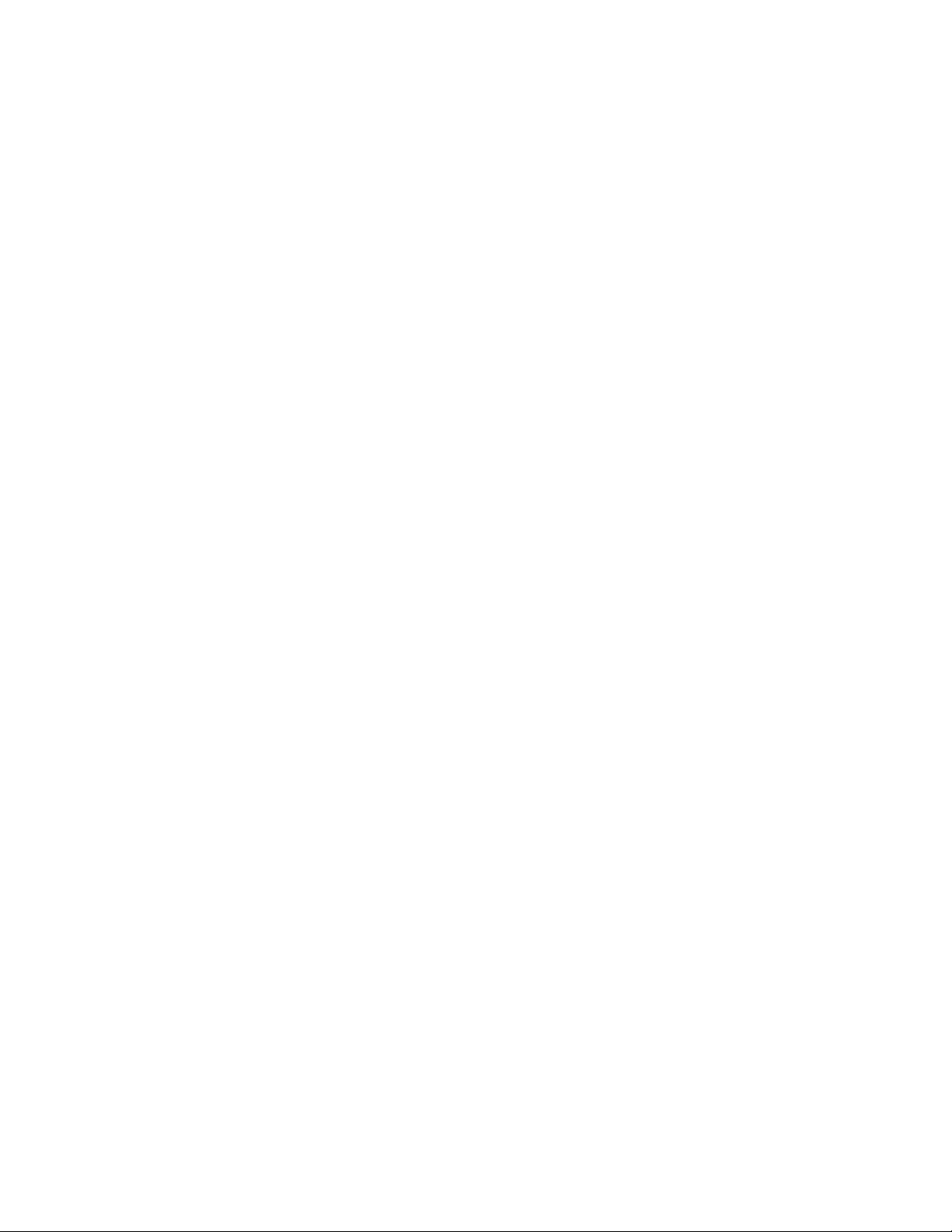

mm and an inner diameter of 1 mm, connects the sensor tip

we will investigate the influence of local deformation and the

to the acoustic housing. A sensor prototype is fabricated, as

frequency of the input wave on the sensor output to determine

depicted in the Fig. 4c. The total length of the sensor is L=

the suitable frequency range for the sensor. The evaluation

30 cm. The sensor body and acoustic case are produced using

value, denoted as S, represents the change in the sensor

a 3D printer with photopolymer resin material. The elastic

output when local deformation occurs (due to contact force)

component is made from pourable silicone material created

compared to the state without interaction force, as expressed using a 3D-printed mold. in the following, S= (Aout ) −(Aout 2 )2 (6) Ain Ain 0≤∆L≤2 ∆L=0

Since the size of the tactile sensor for cardiac ablation

is typically around 3-4.5 mm [15], ∆Lwill be evaluated

within the range of 0 to 2 mm. The length of the acoustic

cavity L= 300 mm and an absorption coefficient r= 0.7

are used in this analysis. The frequency of the input wave is

varied from fin = 0-8000 Hz. Fig. 3 illustrates the relationship

between local deformation, the frequency of the input wave,

and the evaluation value, S. A higher value of Sindicates

that the sensor output is more sensitive to changes in local

deformation at that frequency. These results show that only a

few frequencies can produce a linear change in sensor output

with respect to local deformation. The appropriate input wave

frequency can be selected based on these results B. Tactile sensor

Fig. 4. Tactile sensor. a) Design of the tactile sensor. b) Sensor tip. c) Sensor

A tactile sensor for cardiac ablation has been developed prototype.

according to the principle described above. The sensor com-

prises a sensor tip, a silicone tube, and an acoustic housing.

The sensor tip, with an outer diameter of 3 mm, comprises C. Measurement system

a sensing component (the elastic component in the proposed

Fig. 5 depicts the measurement system for the tactile sensor.

acoustic principle) and the sensor’s body, which includes an

The system comprises a tactile sensor, a sound card, and a

acoustic cavity with a diameter of 1 mm inside the sensor tip,

personal computer (PC). An input sound wave in the form of

as shown in Fig. 4. The acoustic housing contains a speaker

a sine wave with a frequency of fin = 3080 Hz is generated by

and a microphone for emitting and receiving sound waves,

a generator and the speaker, and it is inserted into the sensor.

respectively. The silicone tube, with an outer diameter of 2

The acoustic signals from the sensor are captured by the

microphone and processed through the sound card, and then

output will be collected starting from this position. The stepper

it is handled by the PC. Within the PC, the amplitude of the

motor will control the vertical stage to move downwards in

sound wave is used to estimate the contact force at the sensor.

the direction of the arrow (as shown in the figure) from the

The output obtained is processed through a digital signal

position of Z= 0 mm to the position of Z= 2 mm, with

processing system programmed within the PC. The signal is

each step being 0.5 mm. At each step, the sensor output and

smoothed using a low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 5

the corresponding force from the F/T sensor will be recorded.

Hz. This approach helps to eliminate any noise present in the

When the position of Z= 2 mm is reached, the vertical stage

sensor’s acoustic cavity. The processed signal is then displayed

is controlled to return to the origin. This process is repeated

in real-time on the PC screen. Based on this measurement three times to collect data.

system, an experiment will be set up to assess the feasibility B. Experimental results

of the developed sensor using the acoustic reflection principle.

Fig. 7 depicts the experimental results. Generally, the sensor

output increases as the applied force increases. The force

range of the developed tactile sensor is from 0 to 1 N. The

relationship between the sensor output and the applied force

could be represented as follows, (Y=aX2+bX +c (7) X=U−U0

where Yand Xare the estimated forces and the sensor Fig. 5. Measurement system.

output (subtraction of actual sensor output value Uand sensor

output value U0at Z= 0), respectively. The polynomial fitting III. EXPERIMENT

method with order n= 2 was used to calculate the calibration

coefficients a, b, and c. The calibration coefficients were given

A. Experimental setup and procedure

as [a, b, c] = [859.043680,26.448668,−0.015438].

Fig. 6 illustrates an experiment to test the response of

the developed tactile sensor. In this experiment, the tactile

sensor is securely mounted on a vertical stage. The vertical

stage is fixed onto a fixture plate using aluminum frames.

The movement of the vertical stage is controlled by a stepper

motor. A commercial F/T force sensor (ATI nano 17), attached

to the fixture plate, is used to measure the forces applied on the tactile sensor. Fig. 7. Experimental results. IV. DISCUSSIONS

Based on the preliminary theoretical analysis results, it

is evident that only at specific frequencies does the sensor

output provide the best signal corresponding to the changes

in local deformation (due to contact force). The theoretical

analysis suggests that the ratio between sensor output and local

deformation increases with frequency. However, a higher slope

leads to greater sensitivity to noise. Additionally, due to the

very small size of the acoustic cavity in tactile sensors, the

resonance characteristics reduce the sensor output amplitude Fig. 6. Experimental setup.

as the frequency increases [45]. Therefore, through experimen-

tation, a suitable frequency of fin = 3080 Hz can be selected,

In this experiment, initially, the tactile sensor is moved close

considering the tactile sensor’s size and design.

to the F/T sensor so that the contact force is equal to 0. At

For cardiac ablation procedures, the diameter of the catheter

this point, we define this as the origin (Z= 0 mm). The sensor

tip is typically 3.5-4 mm [15]. Therefore, with a diameter of

only 3 mm, the tactile sensor developed using the acoustic

[3] G. Hindricks et al., “2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and

reflection principle is perfectly suited for cardiac ablation.

management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the

European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task

Furthermore, the force requirements for the tactile sensor in

Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the

cardiac ablation typically fall within the range of 0–0.5 N [15].

European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special

With a force range of 0–1 N, the tactile sensor can fully meet

contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of

the ESC,” Eur. Heart J., vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 373–498, 2021, doi:

the force working range requirements while ensuring that the 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612.

sensor does not become overloaded. Additionally, the 5 Hz

[4] G. Y. H. Lip et al., “Atrial fibrillation,” Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers, vol. 2,

filter currently used for the sensor can adequately satisfy the

no. 1, 2016, doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.16.

sensor’s operating bandwidth requirement of 2 Hz [15].

[5] S. S. Chugh et al., “Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: A

Global Burden of Disease 2010 study,” Circulation, vol. 129, no. 8, pp.

Although the initial theoretical analysis and experiments

837–847, 2014, doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.113.005119.

have yielded promising results regarding the feasibility of the

[6] G. Lippi, F. Sanchis-Gomar, and G. Cervellin, “Global epidemiol-

acoustic reflection principle and the tactile sensor prototype

ogy of atrial fibrillation: An increasing epidemic and public health

challenge,” Int. J. Stroke, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 217–221, 2021, doi:

for cardiac ablation, some areas still need improvement in the 10.1177/1747493019897870.

future. Regarding theoretical foundations, the length Land

[7] E. Kodani and H. Atarashi, “Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in Asia

absorption coefficient rare currently held constant for the pre-

and the world,” J. Arrhythm., vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 330–337, 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2012.07.001.

liminary assessment of the proposed acoustic principle. These

[8] S. Dokos, Modelling organs, tissues, cells and devices. Berlin, Heidel-

parameters will be varied in future research to observe the

berg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2017.

sensor’s response. Furthermore, other factors, such as cavity

[9] P. Polygerinos, D. Zbyszewski, T. Schaeffter, R. Razavi, L. D. Senevi-

ratne, and K. Althoefer, “MRI-compatible fiber-optic force sensors

size or sensor material, will be investigated to optimize the

for catheterization procedures,” IEEE Sens. J., vol. 10, no. 10, pp.

principle. Regarding the sensor, the current length L= 30 cm is

1598–1608, 2010, doi: 10.1109/jsen.2010.2043732.

relatively short for a cardiac ablation procedure. In the future,

[10] H. W. Cao, “Irrigated ablation catheter having a pressure sensor to detect

we will develop a longer sensor with higher applicability for

tissue contact,” Sep. 22, 2009

[11] P. Polygerinos, A. Ataollahi, T. Schaeffter, R. Razavi, L. D. Seneviratne,

actual cardiac ablation procedures. Additionally, experiments

and K. Althoefer, “MRI-compatible intensity-modulated force sensor for

involving the application of the sensor to actual tissue will be

cardiac catheterization procedures,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 58,

conducted in further work to evaluate the effectiveness of the

no. 3, pp. 721–726, 2011, doi: 10.1109/TBME.2010.2095853.

[12] A. L. Trejos, R. V. Patel, and M. D. Naish, “Force sensing and its developed sensor.

application in minimally invasive surgery and therapy: A survey,” Proc

Inst Mech Eng Part C, vol. 224, no. 7, pp. 1435–1454, 2010, doi: 10.1243/09544062jmes1917. V. CONCLUSIONS

[13] G. S. Guthart and J. K. Salisbury, “The Intuitive/sup TM/ telesurgery

system: overview and application,” in Proceedings 2000 ICRA. Mil-

This study proposes a novel acoustic reflection principle

lennium Conference. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and

for developing a tactile sensor for cardiac ablation. In this

Automation. Symposia Proceedings (Cat. No.00CH37065), IEEE, 2002.

principle, the sensing area is located at the distal end of the

[14] P. Puangmali, K. Althoefer, L. D. Seneviratne, D. Murphy, and P.

Dasgupta, “State-of-the-art in force and tactile sensing for minimally

acoustic cavity, which minimizes the tactile sensor’s size. The

invasive surgery,” IEEE Sens. J., vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 371–381, 2008, doi:

preliminary theoretical analysis showed that only several fre- 10.1109/jsen.2008.917481.

quencies could provide a strong sensor output when the contact [15] V. S. N. Sitaramgupta, D. Padmanabhan, P. S. M. Rao, and H. J.

Pandya, “Force sensing technologies for catheter ablation procedures,”

force is applied to the sensing area of the acoustic cavity. The

Mechatronics (Oxf.), vol. 64, no. 102295, p. 102295, 2019, doi:

tactile sensor was developed based on the proposed acoustic

10.1016/j.mechatronics.2019.102295.

principle. The sensor is made of biocompatible materials and

[16] K. Yokoyama et al., “Novel contact force sensor incorporated in irrigated

radiofrequency ablation catheter predicts lesion size and incidence of

has advantages in medical environments, such as electrical

steam pop and thrombus,” Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol., vol. 1, no.

safety and sterilization. Moreover, the sensor is small enough

5, pp. 354–362, 2008, doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.803650.

(diameter of 3 mm) for catheterization. Experimental results

[17] S. R. Dukkipati et al., “Electroanatomic mapping of the left ventricle

in a porcine model of chronic myocardial infarction with magnetic

demonstrated that the sensor output increases with the applied

resonance-based catheter tracking,” Circulation, vol. 118, no. 8, pp.

force and that the force range is sufficient for cardiac ablation

853–862, 2008, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.738229.

procedures. The tactile sensor’s structure will be improved

[18] P. Polygerinos, L. D. Seneviratne, R. Razavi, T. Schaeffter, and K.

to optimize the sensor output response in future work. Fur-

Althoefer, “Triaxial catheter-tip force sensor for MRI-guided cardiac

procedures,” IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron., vol. 18, no. 1, pp.

thermore, practical experiments involving actual tissue will be

386–396, 2013, doi: 10.1109/tmech.2011.2181405.

conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the tactile sensor

[19] P. Nordbeck et al., “Cardiac catheter ablation under real-time magnetic

using the acoustic principle for cardiac ablation and other

resonance guidance,” Eur. Heart J., vol. 33, no. 15, pp. 1977–1977, 2012, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs139. medical procedures.

[20] P. Polygerinos, P. Puangmali, T. Schaeffter, R. Razavi, L. D. Seneviratne,

and K. Althoefer, “Novel miniature MRI-compatible fiber-optic force

sensor for cardiac catheterization procedures,” in 2010 IEEE Interna- REFERENCES

tional Conference on Robotics and Automation, IEEE, 2010.

[21] R. D. Nawfel, P. F. Judy, S. G. Silverman, S. Hooton, K. Tuncali, and

[1] J. Klingelh¨ofer and D. Sander, “Cardiovascular consequences of clinical

D. F. Adams, “Patient and personnel exposure during CT fluoroscopy-

stroke,” Baillieres. Clin. Neurol., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 309–335, 1997.

guided interventional procedures,” Radiology, vol. 216, no. 1, pp.

[2] P. S¨or¨os and V. Hachinski, “Cardiovascular and neurological causes of

180–184, 2000, doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl39180.

sudden death after ischaemic stroke,” Lancet Neurol., vol. 11, no. 2, pp.

[22] F. Schiele et al., “Intravascular ultrasound–guided balloon angioplasty

179–188, 2012, doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70291-5.

compared with Stent: Immediate and 6-month results of the multicenter,

randomized Balloon Equivalent to Stent study (BEST),” Circulation, vol.

sive Ther. Allied Technol., vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 52–60, 2010, doi:

107, no. 4, pp. 545–551, 2003, doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047212.94399.7e 10.3109/13645700903516742.

[23] Y. Khaykin et al., “Intracardiac ECHO integration with three dimen-

[43] J. A. Dobrzynska and M. A. M. Gijs, “Polymer-based flexible capacitive

sional mapping: Role in AF ablation,” J. Atr. Fibrillation, vol. 1, no. 2,

sensor for three-axial force measurements,” J. Micromech. Microeng.,

p. 32, 2008, doi: 10.4022/jafib.32.

vol. 23, no. 1, p. 015009, 2013, doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/23/1/015009.

[24] Catheter ablation of cardiac arrhythmias. Elsevier, 2011.

[44] H. Su et al., “Fiber-optic force sensors for MRI-guided interventions and

[25] K. Yokoyama et al., “Novel contact force sensor incorporated in irrigated

rehabilitation: A review,” IEEE Sens. J., vol. 17, no. 7, pp. 1952–1963,

radiofrequency ablation catheter predicts lesion size and incidence of

2017, doi: 10.1109/jsen.2017.2654489.

steam pop and thrombus,” Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol., vol. 1, no.

[45] Y. Tanaka, T. Fukuda, M. Fujiwara, and A. Sano, “Tactile sensor using

5, pp. 354–362, 2008, doi: 10.1161/circep.108.803650.

acoustic reflection for lump detection in laparoscopic surgery,” Int. J.

[26] Z. Issa and J. M. Miller, Clinical arrhythmology and electrophysiology:

Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 183–193, 2015, doi:

A companion to braunwald’s heart disease, 2nd ed. London, England: 10.1007/s11548-014-1067-z. W B Saunders, 2012.

[46] H. H. Ly, Y. Tanaka, and M. Fujiwara, “A tactile sensor using the

[27] Y. Okumura, S. B. Johnson, T. J. Bunch, B. D. Henz, C. J. O’brien,

acoustic reflection principle for assessing the contact force component in

and D. L. Packer, “A systematical analysis ofin vivocontact forces on

laparoscopic tumor localization,” Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg.,

virtual catheter tip/tissue surface contact during cardiac mapping and

vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 289–299, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s11548-020-02294-w.

intervention,” J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol., vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 632–640,

[47] H. H. Ly, Y. Tanaka, T. Fukuda, and A. Sano, “Grasper having tactile

2008, doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01135.x.

sensing function using acoustic reflection for laparoscopic surgery,” Int.

[28] T. Lin, F. Ouyang, K.-H. Kuck, and R. Tilz, “ThermoCool® Smart-

J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg., vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 1333–1343, 2017,

Touch® Catheter – the evidence so far for contact force technology and

doi: 10.1007/s11548-017-1592-7.

the role of VisiTag module,” Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. Rev., vol. 3, no.

[48] T. Ukai, Y. Tanaka, T. Fukuda, T. Kajikawa, H. Miura, and Y. Terada,

1, pp. 44–47, 2014, doi: 10.15420/aer.2011.3.1.44.

“Softness sensing probe with multiple acoustic paths for laparoscopic

[29] A. Thiagalingam et al., “Importance of catheter contact force during

surgery,” Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg., vol. 15, no. 9, pp.

irrigated radiofrequency ablation: Evaluation in a porcineex vivomodel

1537–1547, 2020, doi: 10.1007/s11548-020-02207-x.

using a force-sensing catheter,” J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol., 2010, doi:

10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01693.x.

[30] H. J. Pandya, J. Sheng, and J. P. Desai, “Towards a tri-axial flexible

force sensor for catheter contact force measurement,” in 2016 IEEE SENSORS, IEEE, 2016.

[31] L. Di Biase et al., “Visual, tactile, and contact force feedback: Which

one is more important for catheter ablation? Results from an in vitro

experimental study,” Heart Rhythm, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 506–513, 2014,

doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.11.016.

[32] H. J. Pandya, K. Park, and J. P. Desai, “Design and fabrication of a

flexible MEMS-based electro-mechanical sensor array for breast cancer

diagnosis,” J. Micromech. Microeng., vol. 25, no. 7, p. 075025, 2015,

doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/25/7/075025.

[33] S. W. Hetts et al., “Endovascular catheter for magnetic navigation

under MR imaging guidance: evaluation of safety in vivo at 1.5T,”

AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol., vol. 34, no. 11, pp. 2083–2091, 2013, doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3530.

[34] B. Han, Y.-J. Yoon, M. Hamidullah, A. T.-H. Lin, and W.-T. Park,

“Silicon nanowire-based ring-shaped tri-axial force sensor for smart

integration on guidewire,” J. Micromech. Microeng., vol. 24, no. 6, p.

065002, 2014, doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/24/6/065002.

[35] J. Rad ´ o et al., “3D force sensors for laparoscopic surgery tool,”

Microsyst. Technol., vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 519–525, 2018, doi: 10.1007/s00542-017-3443-4.

[36] L. Beccai et al., “Design and fabrication of a hybrid silicon three-axial

force sensor for biomechanical applications,” Sens. Actuators A Phys.,

vol. 120, no. 2, pp. 370–382, 2005, doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2005.01.007.

[37] N. Thanh-Vinh, N. Binh-Khiem, H. Takahashi, K. Matsumoto, and I.

Shimoyama, “High-sensitivity triaxial tactile sensor with elastic mi-

crostructures pressing on piezoresistive cantilevers,” Sens. Actuators A

Phys., vol. 215, pp. 167–175, 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2013.09.002.

[38] P. Valdastri et al., “Miniaturized cutting tool with triaxial force sensing

capabilities for minimally invasive surgery,” J. Med. Device., vol. 1, no.

3, pp. 206–211, 2007, doi: 10.1115/1.2778700.

[39] H. Nakagawa et al., “Locations of high contact force during left

atrial mapping in atrial fibrillation patients: Electrogram amplitude and

impedance are poor predictors of electrode-tissue contact force for

ablation of atrial fibrillation,” Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol., vol. 6,

no. 4, pp. 746–753, 2013, doi: 10.1161/circep.113.978320.

[40] C. Chi, X. Sun, N. Xue, T. Li, and C. Liu, “Recent progress in

technologies for tactile sensors,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 18, no. 4, p. 948, 2018, doi: 10.3390/s18040948.

[41] M. Kalantari, M. Ramezanifard, R. Ahmadi, J. Dargahi, and J.

K¨ovecses, “A piezoresistive tactile sensor for tissue characterization

during catheter-based cardiac surgery: Tactile sensor for catheter-based

technique,” Int. J. Med. Robot., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 431–440, 2011, doi: 10.1002/rcs.413.

[42] H. Wang, P. X. Liu, S. Guo, and X. Ye, “A catheter side wall

tactile sensor: Design, modeling and experiments,” Minim. Inva-