Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Page 3 CHAPTER 1

Assurance and auditing: an overview

LEARNING OBJECTIVES (LO) 1.1

Understand the framework for assurance engagements and the types of

assurance engagements that can be provided. 1.2

Define auditing and appreciate the fundamental principles underlying an audit. 1.3

Appreciate the attributes of accounting information and understand the

reasons giving rise to demand for assurance and resulting benefits. 1.4

Explain the concept of the expectation gap, especially in the areas of

auditor’s report messages, corporate failures, fraud and communicating

different levels of assurance, and appreciate the relationships between

the auditor, the client and the public. 1.5

Appreciate the role of auditing standards and their authority under the Corporations Act 2001. 1.6

Obtain an overview of other applications of the assurance function,

including compliance engagements, performance engagements,

comprehensive engagements, internal auditing and forensic auditing, as

well as of providing assurance on subject matter other than historical financial information. RELEVANT GUIDANCE ASA 102

Compliance with Ethical Requirements when

Performing Audits, Reviews and Other Assurance Engagements ASA 200/ISA 200

Overall Objectives of the Independent Auditor and the

Conduct of an Audit in Accordance with Australian

(International) Auditing Standards lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 ASA 220/ISA 220

Quality Control for an Audit of a Financial Report and

Other Historical Financial Information ASAE 3000/ISAE 3000

Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or

Reviews of Historical Financial Information

Conformity with Auditing and Assurance Standards APES 210

Foreword to AUASB Pronouncements AUASB

AUASB Glossary/Glossary of Terms AUASB/IAASB

Framework for Assurance AUASB/IAASB

Engagements/International Framework for Assurance Engagements

Preface to the International Standards on Quality IAASB

Control, Auditing, Review, Other Assurance and Related Services Page 4 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

CHAPTER OUTLINE AND REVIEW OF CURRENT AUDITING ENVIRONMENT

Entities achieve their goals through the use of human and economic resources. In

order to account for the use of these human and economic resources, entities issue

reports explaining the use of the resources entrusted to their control.

These reports can take a number of forms, including financial reports, which are

prepared in accordance with accounting standards in order to provide information on

the financial position and performance of an entity, and environmental reports, which

are prepared in accordance with environmental standards to provide information on

the environmental performance of an entity. A primary function of the auditing and

assurance profession is to provide independent and expert opinions on these reports

based on an examination of the evidence underlying the information reported, in order

to improve the credibility of these reports.

Auditors usually bring two major types of expertise to an audit. One of these is an

expertise on the subject matter of the underlying report. For example, if the audit is of

a financial report, this requires expertise on the accounting standards and regulations

that underpin the financial report. Students will have started to develop this expertise

by undertaking the financial accounting subjects contained in an accounting degree,

and will further develop it in practice.

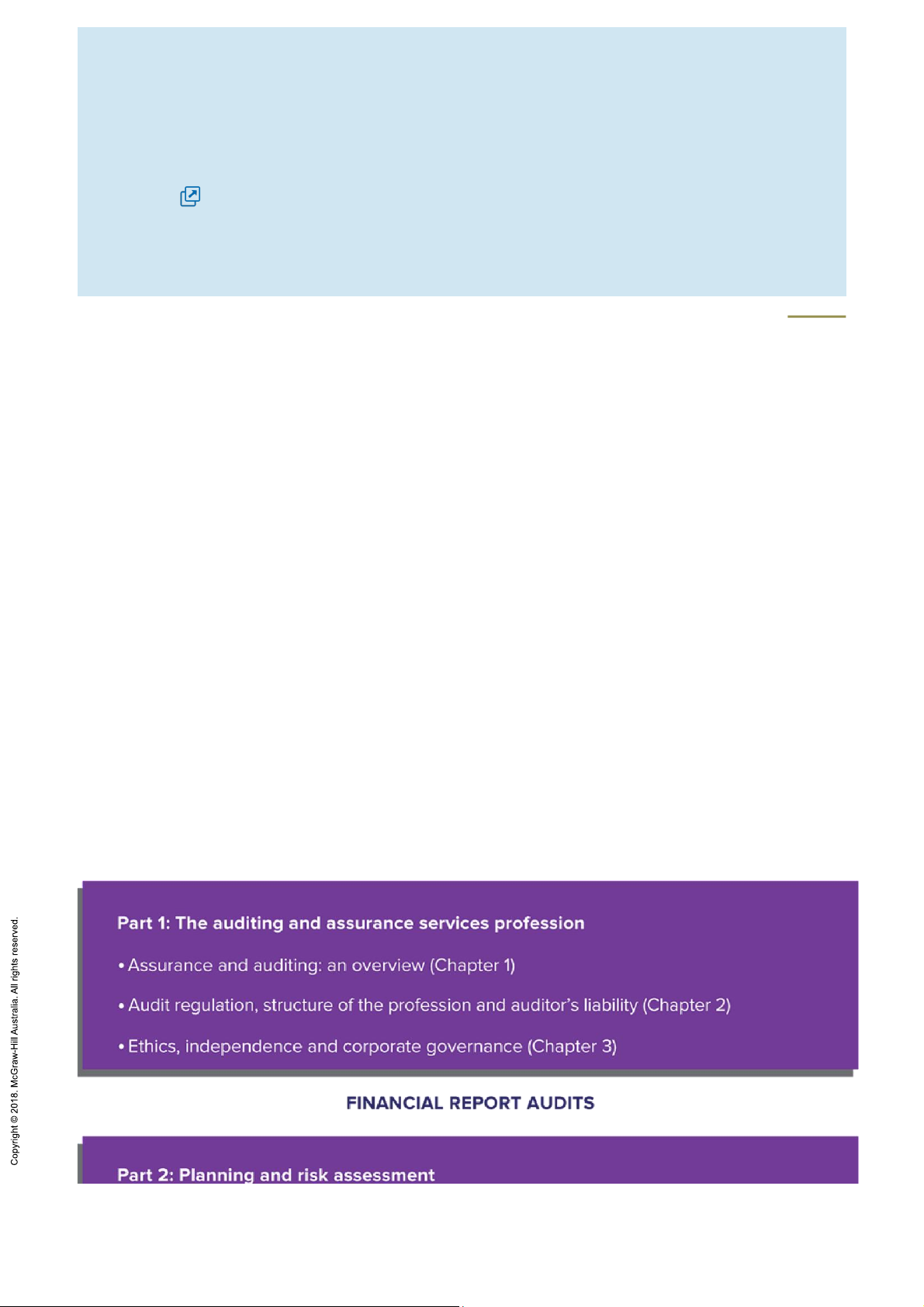

The second major type of expertise is auditing and assurance expertise. This involves,

firstly, understanding the auditing and assurance services profession (Chapters 1 – 3

). Further, for any particular engagement, it involves appropriately planning and

assessing risk, including developing an understanding of the reporting entity and of the

industry and environment in which it operates, assessing the major risks of

misstatement in the underlying report (Chapters 4 –7 ), collecting audit evidence

so that the risk of misstatement is reduced to an acceptably low level (Chapters 8 – 10

) and effectively communicating the findings (Chapters 11 –12 ). This book

explains this process and helps to develop this expertise.

The auditor has developed the audit process and their own expertise and reputation in

the area of auditing financial reports. However, this process and expertise can be

applied to areas other than financial reports, such as providing lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

assurance on an entity’s disclosure of its corporate social responsibility or its level of

carbon emissions. The concept of applying the audit process more

broadly is introduced in this chapter and discussed further in Chapters 13 –15 .

Figure 1.1 outlines the way the text works through the various stages of the audit

process in a logical manner. Each step in the process builds on the steps that precede it.

This framework is expanded upon in each chapter of the text. Page 5 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

FIGURE 1.1 Flowchart of overall auditing and assurance framework Page 6

LO 1.1 The framework for assurance engagements and the

types of assurance engagements

Framework for assurance engagements

In many situations in today’s society, people who are responsible for a specific task (called

responsible parties or managers) need to account for their performance with respect to lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

that task. There may be many groups who will rely on this accounting for performance as

an aid to their decision making. These groups may be either resource providers or third

parties to the process (other users). There are many examples of such relationships, including:

shareholders relying on financial reports produced by a company’s management

government agencies relying on reports produced by entities to account for

environmental considerations parents relying on information produced by schools or

contained on websites, when deciding where to send their children.

In order for users to be able to judge the performance of the responsible party, they may

ask the responsible party to provide them with a report of how the resources under their

care have been used in achieving the aims of the relationship. However, it is recognised

that the report by the responsible party is potentially biased, as the responsible party may

have an incentive to prepare a report that reflects their own performance in the best

possible light. Thus, before the report is made available to the user, the credibility of the

report is enhanced by having someone who is both independent and expert (called the

auditor or assurance service provider) examine that the underlying subject matter of

the report is prepared and presented in accordance with an agreed reporting framework

(called suitable criteria ) and provide an assessment (the audit or assurance report) that

accompanies the report prepared by the responsible party.

The International Framework for Assurance Engagements, issued by the International

Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) (and in Australia by the Australian

Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB) as the Framework for Assurance

Engagements), covers both audits and reviews of historical financial information and all

other assurance engagements. This initiative therefore recognises the increasing demand

for assurance over a wide range of subject matter.

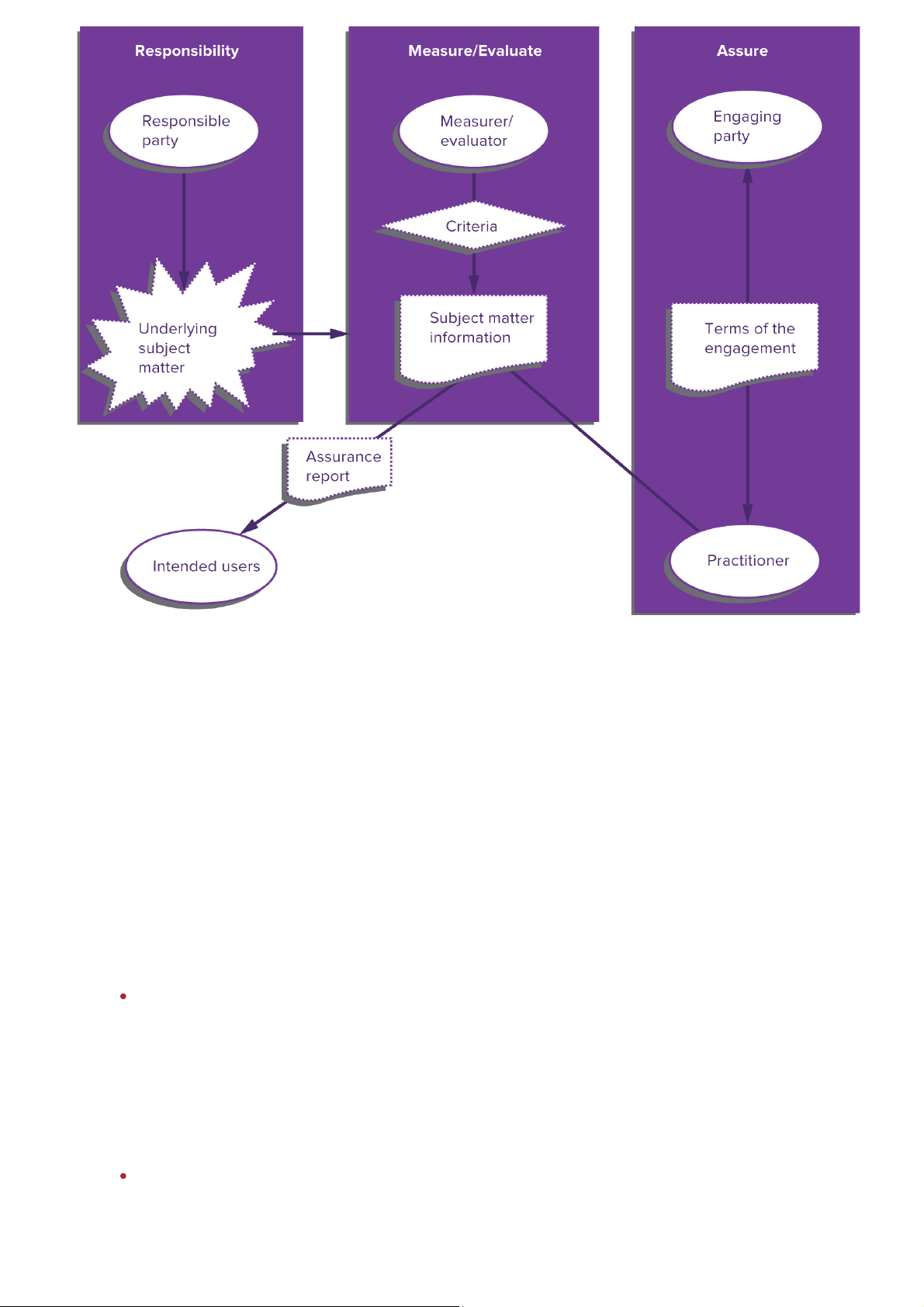

The framework defines an assurance engagement as ‘an engagement in which a

practitioner aims to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence in order to express a

conclusion designed to enhance the degree of confidence of the intended users other

than the responsible party about the outcome of the measurement or evaluation of an

underlying subject matter against criteria’ (paragraph 10). Figure 1.2 is a diagrammatic

summary of the interrelationship of the five components, which are discussed below. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

FIGURE 1.2 The parties to an assurance engagement

Source: ASAE 3000 Appendix 1/ISAE 3000 Appendix 1. (c) 2018 Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB). The

text, graphics and layout of this publication are protected by Australian copyright law and the comparable law of other

countries. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the

prior written permission of the AUASB except as permitted by law. For reproduction or publication permission should be

sought in writing from the Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. Requests in the first instance should be addressed to

the Technical Director, Auditing and Assurance Standards Board, PO Box 204, Collins Street West, Melbourne, Victoria, 8007.

The following five elements of an assurance engagement are identified (paragraph 26 of the assurance framework): 1.

Three-party relationship

Assurance practitioner (auditor) This is the individual(s) undertaking the assurance

engagement. In Australia this would normally be a member of a recognised

accounting body (CPA Australia, Chartered Accountants Australia and New

Zealand (Chartered Accountants ANZ) or the Institute of Public Accountants (IPA)),

and one who is bound by the profession’s code of ethics.

Responsible party This is the person or persons responsible for the underlying

subject matter. For example, the board of directors (responsible party) is

responsible for the financial position and performance of the entity, which is lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

communicated by a financial report. In many attestation engagements, the

responsible party may also be the measurer or evaluator and the engaging

party . Where the financial report is the subject matter information,

management is designated as the measurer/evaluator.

Intended users These are the persons expected to use the assurance practitioner’s

report. Often the intended users will be the addressees of the report by the

assurance practitioner, although there will be circumstances where there will be other identified users. Page 7 2.

Underlying subject matter The underlying subject matter of an assurance

engagement can take many forms, such as:

financial position and performance (for example, historical or prospective financial information)

non-financial performance (for example, information aimed at efficiency and

effectiveness of use of resources or level of carbon emissions) physical

characteristics (for example, capacity of a facility) systems and processes

(for example, internal controls)

behaviour (for example, corporate governance, compliance with regulation, human resource practices).

Thus, the definition of assurance engagements is very broad in its coverage and

includes both existing assurance engagements and newly evolving assurance

engagements. The framework also draws a distinction between the underlying

subject matter (such as the underlying financial position and performance of an

entity) and the report on the subject matter, which is called subject matter

information (such as the statements of financial position and income statements). 3.

Criteria Suitable criteria are the standards or benchmarks used to measure and

evaluate the underlying subject matter of an assurance engagement. Criteria are

important in the reporting of a conclusion by an assurance practitioner, as they

establish and convey to the intended user the basis on which the conclusion has

been formed. For example, the criteria used for preparing a financial report may be

Page 8 International Financial Reporting Standards. The auditor then assesses

whether the financial report is prepared in accordance with these criteria. Without

this frame of reference any conclusion is open to individual interpretation and misunderstanding. 4.

Sufficient appropriate evidence The engagement process for an assurance

engagement is a systematic methodology requiring specialised knowledge, a skill

base and techniques for evidence gathering and evaluation to support a conclusion,

irrespective of the nature of the underlying subject matter. Underlying the process

is the assurance practitioner gathering sufficient appropriate evidence that the lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

subject matter information (e.g. the financial report) has been prepared in

accordance with the criteria (e.g. the accounting standards and relevant legislation)

and appropriately portrays the underlying subject matter (the financial position and

performance of the entity). The process involves the assurance practitioner and

appointing party agreeing to the terms of the engagement. Within that context, the

assurance practitioner considers materiality and the relevant components of

engagement risk when planning the engagement and collecting sufficient and appropriate evidence. 5.

A written assurance report The assurance practitioner presents a written

conclusion that provides a level of assurance about the underlying subject matter.

Independence and expertise: professional judgment and professional scepticism

The assurance practitioner will seek to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence as the basis

for the provision of the level of assurance. In conjunction with the nature and form of the

underlying subject matter, criteria and procedures, the reliability of the evidence itself

can impact on the overall sufficiency and appropriateness of the evidence available.

There are a number of characteristics that make it appropriate for the profession to

provide assurance on a range of underlying subject matter. As mentioned earlier, the

profession is leveraging off its reputation as a high-quality professional provider of

assurance services. In particular, it is the independence and expertise of the assurance

practitioner that are sought after.

Users derive value from the knowledge that the assurance provider has no interest in the

information other than to enhance its credibility. Assurance independence is an absence

of interests that create an unacceptable risk of material bias with respect to the quality or

content of information that is the subject of an assurance engagement. Independence

remains the cornerstone on which the assurance function is based, and will be discussed

in more detail in Chapter 3 .

The exercise of professional judgment permeates the notion of professional service. An

assurance service engagement requires the exercise of professional judgment (ASA

200.16/ISA 200.16), which involves the application of relevant training, knowledge and

experience in making informed decisions about the courses of action that are appropriate

in the circumstances of the assurance engagement. The auditor should also plan and

perform the assurance engagement with professional scepticism , which is an attitude lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

that includes a questioning mind, being alert to conditions that may indicate possible

misstatement due to error or fraud, and a critical assessment of audit evidence (ASA

200.15/ISA 200.15). The provision of a professional service requires the assurance

practitioner to offer only those services that they have the competence to complete, to

exercise due care in the performance of the service, to adequately plan and supervise the

performance of the service and to obtain sufficient relevant information to provide a

reasonable basis for conclusions or recommendations. Consideration must also be given

to the appropriateness of measurement criteria and to the need to communicate the

engagement results. Users can obtain assurance from the service only if they are aware of

the assurance practitioner’s involvement.

It could be argued that professional reputation is the critical factor that adds value to the

assurance services offered by the professional accountant. As a profession, we need to

protect or even improve the profession’s brand name, thus enhancing the value of the

assurance services. A further advantage to having members of the accounting profession

provide assurance is that accountants are subject to many professional quality Page 9

controls and disciplining mechanisms, and this should provide assurance to users about

the quality of the inputs to and processes of our services, and therefore the quality of the

final report, the output. It is through this process that assurance services add value.

Whether the accounting profession is successful in becoming the most appropriate group

for providing assurance in a wide range of areas will depend on a number of factors,

including whether society sees accountants as experts in the underlying subject matter of

the assurance engagement. Financial report auditors are expert in the subject matter of

accounting information prepared in accordance with accounting standards, and have

developed processes and a reputation as high-quality assurance providers. Whether this

reputation easily transfers to other areas—such as providing assurance on environmental

reports (or, as argued in Huggins et al., 2011, greenhouse gas reports), and possibly as a

high-cost provider given the necessity of having high-level ethical standards and quality

controls in place associated with being a member of the accounting profession—will be the test of success. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

Types of assurance engagements

Reasonable, limited and agreed-upon procedures engagements

The assurance framework (paragraphs 14–16) outlines that an assurance practitioner can

enter into two types of assurance engagements or, effectively, provide two levels of

assurance on any particular type of assurance engagement. These two types of assurance

engagements are reasonable assurance engagements and limited assurance engag

ements . For assurance services on historical financial information, a reasonable

assurance engagement is termed an audit , and a limited assurance engagement is

termed a review engagement . The objective of a reasonable assurance engagement

(audit) is a reduction in assurance engagement risk to an acceptably low level in the

circumstances of the engagement as a basis for the practitioner’s conclusion. This

conclusion is expressed in a form that conveys the practitioner’s opinion on the outcome

of the assessment of the underlying subject matter against the criteria (such as, ‘in my

opinion the financial information is presented in accordance with International Financial

Reporting Standards’). The objective of a limited assurance engagement (review) is a

reduction in assurance engagement risk to a level that is acceptable in the

circumstances—but where the remaining risk is greater than with a reasonable assurance

engagement— as the basis for expressing a conclusion in a form that conveys whether,

based on procedures performed and evidence obtained, any matter has come to the

auditor’s attention to persuade them that the information has been materially misstated

(see also Chapter 13 ). The differences between reasonable and limited assurance

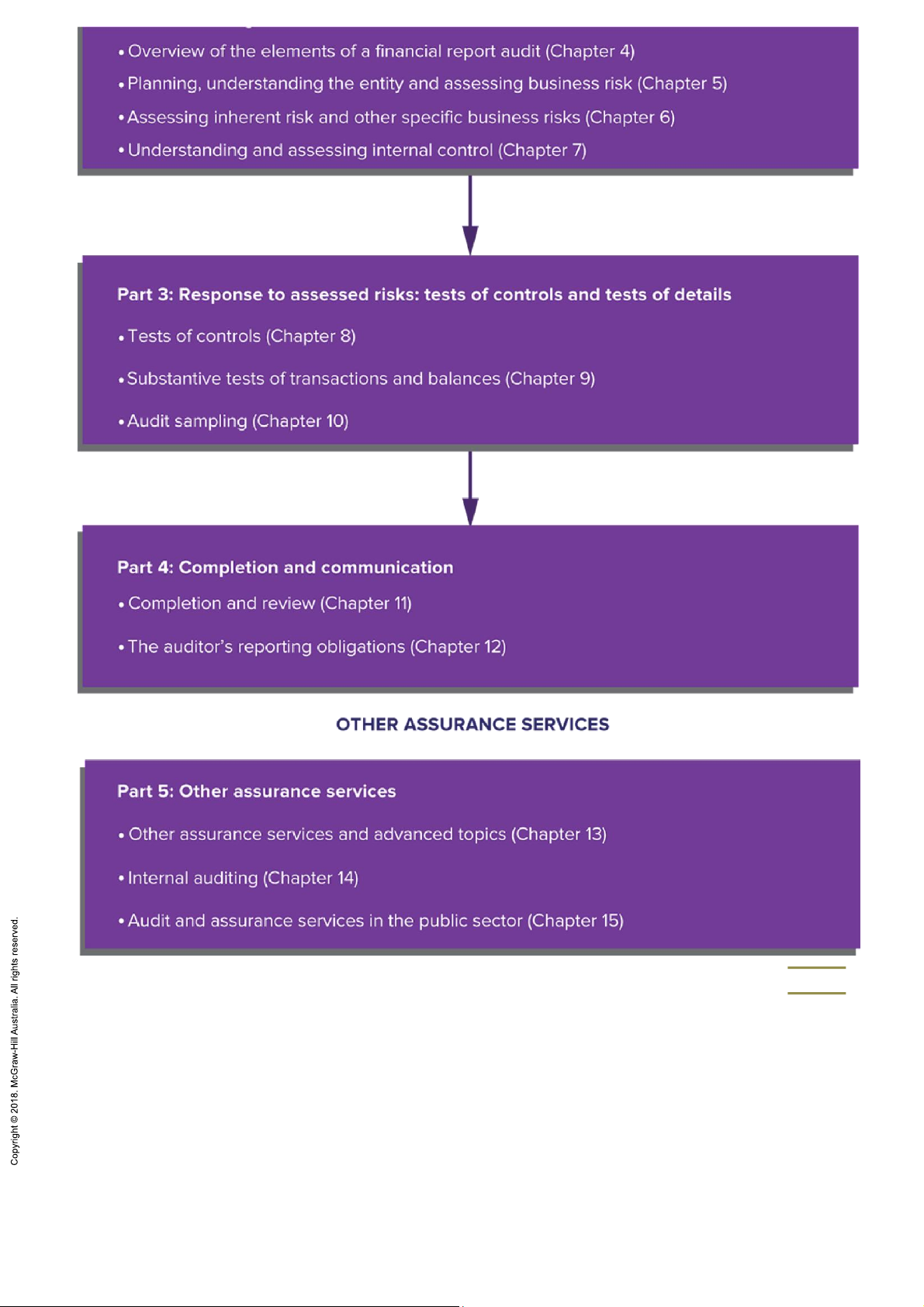

engagements are summarised in Figure 1.3 . lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Type of

Evidence-gathering procedures Assurance report engagement Objective Reasonable A reduction in Sufficient appropriate The assurance assurance evidence is obtained as part practitioner’s engagement

engagement risk of a systematic engagement conclusion is

to an acceptably process that includes: expressed in a form that conveys low level obtaining an the practitioner’s under the understanding of the opinion on the circumstances of engagement outcome of the circumstances assessing

the engagement. risks responding to assessment of the assessed underlying subject risks matter against the criteria. performing further procedures using a combination of inspection, observation, confirmation, recalculation, reperformance, analytical procedures and enquiry (such further procedures involve substantive procedures, including, where applicable, obtaining corroborating information, and tests, depending on the nature of the underlying subject matter, of the operating effectiveness of controls) evaluating the evidence obtained. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Limited A reduction in assurance Sufficient appropriate The engagement assurance evidence is obtained as part engagement practitioner’s of a systematic engagement risk to a level that conclusion is process that includes is obtaining an understanding expressed in a

acceptable under of the underlying subject form that conveys whether, based the matter and other on procedures

circumstances of engagement circumstances, but in which procedures are performed and the deliberately evidence engagement lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 but where that

limited relative to a reasonable obtained, any risk is greater assurance engagement. matter has come than for a to the auditor’s reasonable attention to assurance persuade them engagement. that the information has been materially misstated.

FIGURE 1.3 Differences between reasonable assurance and limited assurance engagements

Source: Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (April 2010), Framework for Assurance

Engagements, Appendix 1. (c) 2018 Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB). The text, graphics and layout of this

publication are protected by Australian copyright law and the comparable law of other countries. No part of the

publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission

of the AUASB except as permitted by law. For reproduction or publication permission should be sought in writing from the

Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. Requests in the first instance should be addressed to the Technical Director,

Auditing and Assurance Standards Board, PO Box 204, Collins Street West, Melbourne, Victoria, 8007.

It is also possible to provide a third type of engagement, termed a related services enga

gement , which covers in particular an agreed-upon procedures engagement .

While this type of engagement involves the use of assurance techniques such as

evidencecollection procedures, it does not involve an attempt to communicate a level of

assurance. A significant difference of this type of engagement from an assurance

engagement is that the auditor does not have the discretion to undertake evidence-

collection procedures outside those that have been agreed upon. The auditor therefore

only issues a report of fact ual findings to the parties that have agreed to the

procedures being performed, in which no conclusion is communicated and which

therefore expresses no assurance. However, it provides the user with information to meet

a particular need, from which the user can draw conclusions and derive their own level of

assurance as a result of the auditor’s procedures.

The assurance framework (paragraph 17) states that the framework, and therefore all

assurance pronouncements, does not cover agreed-upon procedures engagements, the

compilation of financial information engagements, management consulting services, or

the preparation of tax returns where there is no conclusion conveying a level of

assurance. An auditor who undertakes such engagements is required to apply procedures

and an appropriate level of professional skill and care. This may involve having due regard lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

to auditing pronouncements insofar as they are relevant or adaptable to the work being

undertaken. However, this work is not deemed to be of an assurance nature. Page 10

Attestation and direct engagements

It is also necessary to distinguish between an attestation engagement and a direct eng

agement . An attestation engagement requires a party other than the auditor to

measure or evaluate the underlying subject matter against the criteria (paragraph 12 of

the assurance framework). The audit of a general-purpose financial report is an example

of an attestation engagement. A direct engagement requires the auditor to directly

measure or evaluate the underlying subject matter against the criteria. For example, an

auditor’s report could be issued on the adequacy of internal control. Where management

does not measure or evaluate the adequacy of internal control, and therefore the auditor

is required to report directly on its adequacy, the engagement is classed as a direct

engagement. If, however, management has measured or evaluated the adequacy of

internal control and the auditor is required to attest to this statement, it is an attestation engagement.

Audit and assurance engagements are supported by a detailed infrastructure of standards

and pronouncements issued by the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board

(AUASB). Following a policy of convergence in Australia with international Page 11

standards, this infrastructure is similar to the structure of the standards and

pronouncements issued by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board

(IAASB), which is responsible for setting auditing and assurance standards at the

international level. For audits undertaken in Australia under the Corporations Act 2001,

the auditing standards have legal authority and failure to observe these standards may

expose a member to investigation and disciplinary action from the Australian Securities

and Investments Commission (ASIC). The AUASB and the IAASB will be discussed in more

detail in Chapter 2 , as will the structure and the role of auditing and assurance standards.

An example of the importance of high-quality auditing and its contribution to

wellfunctioning markets is contained in Auditing in the global news 1.1 .

1.1 Auditing in the global news ... lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

Why is audit quality important?

Auditors play a critical role in ensuring that Australian investors can be confident

and informed when making investment decisions. High-quality audits support the

quality of financial reports and enable investors to rely on the auditor’s

independent assessment of financial reports.

Audit quality relates to matters that affect the auditor’s ability to achieve an audit’s

fundamental objective: to obtain reasonable assurance that the financial report as a

whole is free of material misstatement. Auditors must ensure any deficiencies

detected are addressed or communicated through the auditor’s report.

Note: This view is consistent with the objective of the audit, as outlined in paragraph

11 of Auditing Standard ASA 200 Overall Objectives of the Independent Auditor and

the Conduct of an Audit in Accordance with Australian Auditing Standards.

Audit quality can be influenced by such factors as:

an audit firm’s culture and focus on audit quality, professional scepticism and consultation

the auditor’s understanding of the business and the risks affecting the financial report

the internal and external experience and expertise applied in audits (including

recruitment and training, the use of experts, and specialist industry knowledge)

how effectively audit engagements are supervised and reviewed (including audit

firm quality reviews) the audit firm’s system of accountability of engagement

partners and others in the firm for audit quality (e.g. impact on remuneration for

poor internal quality review findings).

Source: © Australian Securities & Investments Commission. Reproduced with permission. ‘Audit quality

—the role of directors and audit committees’, Information Sheet 196 (INFO 196), reissued 23 June 2017,

http://asic.gov.au/regulatory-resources/financial-reporting-and-audit/auditors/audit-quality-th e-role-of-

directors-and-audit-committees/. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 QUICK REVIEW 1.

Responsible parties, such as management, prepare reports on how they

have used resources under their care. The credibility of such reports is

enhanced by having an independent expert provide an assurance service on the report. 2.

An assurance engagement is an engagement in which an assurer expresses

a conclusion designed to enhance the degree of confidence of the intended

users other than the responsible party about the outcome of the evaluation

or the measurement of subject matter against criteria. 3.

The five elements of an assurance engagement are:

three-party relationship (assurance practitioner, responsible Page 12 party,

intended users) underlying subject matter suitable criteria sufficient

appropriate evidence a written assurance report. 4.

Users derive value from the assurance report due to the fact that

the assurer: is independent of the underlying subject matter

has the required expertise, applying professional judgment and

professional scepticism. 5.

There are three major types of engagements provided by the auditing and assurance profession:

reasonable assurance engagement (audit) involves a reduction in

assurance engagement risk to an acceptably low level in the circumstances

of the engagement as a basis for the practitioner’s conclusion limited

assurance engagement (review) involves a reduction in assurance

engagement risk to a level that is acceptable in the circumstances—but

where the remaining risk is greater than with a reasonable assurance engagement

agreed-upon procedures involves a report of factual findings, where no

level of assurance is expressed. 6.

Auditing pronouncements are applicable to all assurance engagements, but

not to ‘other service’ engagements, such as consulting engagements, where

the auditor’s objective is to assist or advise the client on any aspect of business management. 7.

An assurance engagement can be either an attestation engagement, where

a party other than the auditor measures or evaluates the underlying subject

matter against the criteria, or a direct engagement, where the auditor lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

undertakes the measurement or evaluation of the underlying subject matter against the criteria. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

LO 1.2 Auditing—definition and fundamental principles

As outlined in the previous section , assurance engagements can be undertaken on

many different types of underlying subject matter, including financial information (for

example, an account of an organisation’s historical financial position and performance),

and non-financial information (for example, an account of an organisation’s corporate

social responsibility). The type of assurance engagement that the auditing profession is

best known for, from which it mainly derives its reputation and is the most commonly

observed in practice, is the audit of historical financial information. Part of the reason for

this is that the requirement for such an audit is contained in many pieces of legislation,

including the Corporations Act 2001, which governs the audit of annual financial reports

for reporting entities. This means that public companies listed on stock exchanges must

have their annual financial reports audited, and it is for this activity that the audit and

assurance profession is best known.

Interestingly, auditing, or the audit of financial reports, is no longer defined in the

AUASB/IAASB Glossary. In ASA 200.11 (ISA 200.11), the objectives of the auditor in

undertaking an audit of a financial report are stated as: (a)

To obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial report as a whole is

free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error, thereby enabling

the auditor to express an opinion on whether the financial report is prepared, in all

material respects, in accordance with an applicable financial reporting framework; and (b)

To report on the financial report, and communicate as required by the Australian

Auditing Standards (ASAs), in accordance with the auditor’s findings.

This definition also underlines the relationship between assurance and audit. Page 13

Assurance covers the range of underlying subject matter information, both financial and

non-financial, while the term audit is used to refer to a subset of assurance engagements,

where the subject matter is financial information prepared in accordance with an

applicable financial reporting framework.

While these objectives describe the expected outcomes, they do not describe what an

audit entails, or the process of auditing . A useful definition is that developed by the

American Accounting Association (AAA) in A Statement of Basic Auditing Concepts

(ASOBAC) (1973). It defines auditing as: