Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Page 135 CHAPTER 4

Overview of elements of the financial report audit process

LEARNING OBJECTIVES (LO) 4.1

Explain the difference between accounting and auditing and the

importance of professional scepticism and professional judgment to auditing. 4.2

Outline the logical process of identifying financial report assertions,

developing specific audit objectives and selecting auditing procedures. 4.3

Explain the relationships between audit procedures and evidence, and

describe common audit procedures used in an audit of a financial report. 4.4

Define sufficient appropriate audit evidence and its relationship to auditing procedures.

4.5Outline the audit risk model.

4.6Explain the concept of materiality.

4.7Define types of audit tests.

4.8Explain how an auditor may use the work of an expert or component auditor. 4.9

Describe the general requirement to document audit work and the contents of audit working papers. RELEVANT GUIDANCE ASA 200/ISA 200

Overall Objectives of the Independent Auditor and the

Conduct of an Audit in Accordance with Australian

(International) Auditing Standards Audit Documentation ASA 230/ISA 230 ASA 315/ISA 315

Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material

Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and Its Environment

Materiality in Planning and Performing an Audit ASA 320/ISA 320 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 ASA 330/ISA 330

The Auditor’s Responses to Assessed Risks

Evaluation of Misstatements Identified during the Audit ASA 450/ISA 450 Audit Evidence ASA 500/ISA 500 ASA 501/ISA 501

Audit Evidence—Specific Considerations for Inventory and

Segment Information/Audit Evidence—Specific Considerations for Selected Items

Auditing Accounting Estimates, Including Fair Value ASA 540/ISA 540

Accounting Estimates, and Related Disclosures

Written Representations ASA 580/ISA 580

Special Considerations—Audits of a Group Financial ASA 600/ISA 600

Report (Including the Work of Component Auditors)

Using the Work of an Auditor’s Expert ASA 620/ISA 620

Forming an Opinion and Reporting on a Financial Report ASA 700/ISA 700

AUASB Glossary/Glossary of Terms AUASB/IAASB

Third Party Access to Audit Working Papers GS 011 Page 136 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 CHAPTER OUTLINE

Although a financial report audit is only one type of assurance engagement, it is the

most common. Therefore, in this chapter an overview of the elements of the financial

report audit process is provided.

While a financial report audit of a complex entity is a complicated process, even the

most complex audit has certain basic elements. This chapter compares financial report

auditing with accounting, and explains the basic elements of the audit process,

including professional scepticism and professional judgment. These building blocks are

necessary to understand how an audit is accomplished in conformity with Australian

auditing standards. Most of the auditor’s work in forming an opinion on the financial

report consists of obtaining and evaluating evidence about the assertions in the

financial report by applying auditing procedures. It is important to understand each of

the elements—audit evidence, materiality, assertions and audit procedures—in order

to comprehend the audit of a financial report, which will be conducted within the

framework of the audit risk model and the client’s business risk.

The auditor must also prepare and maintain adequate audit working papers to

document their work. This chapter explains the function and content of audit working papers.

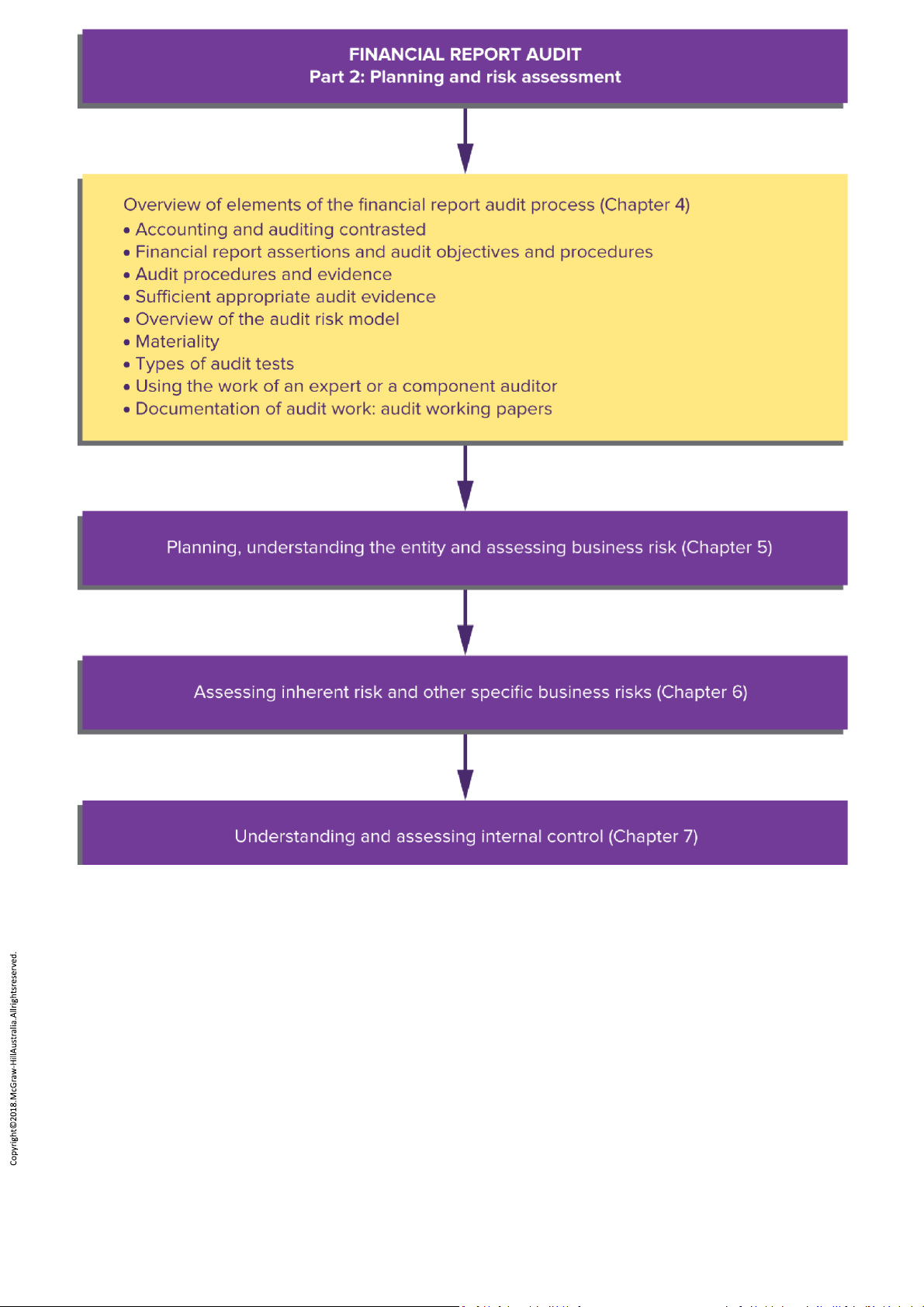

How this chapter fits into the overall financial report audit is illustrated in Figure 4.1

, which is an expansion of part of the overall flowchart provided in Chapter 1 . lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

FIGURE 4.1 Flowchart of planning and risk-assessment stage of a financial report audit lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Page 137

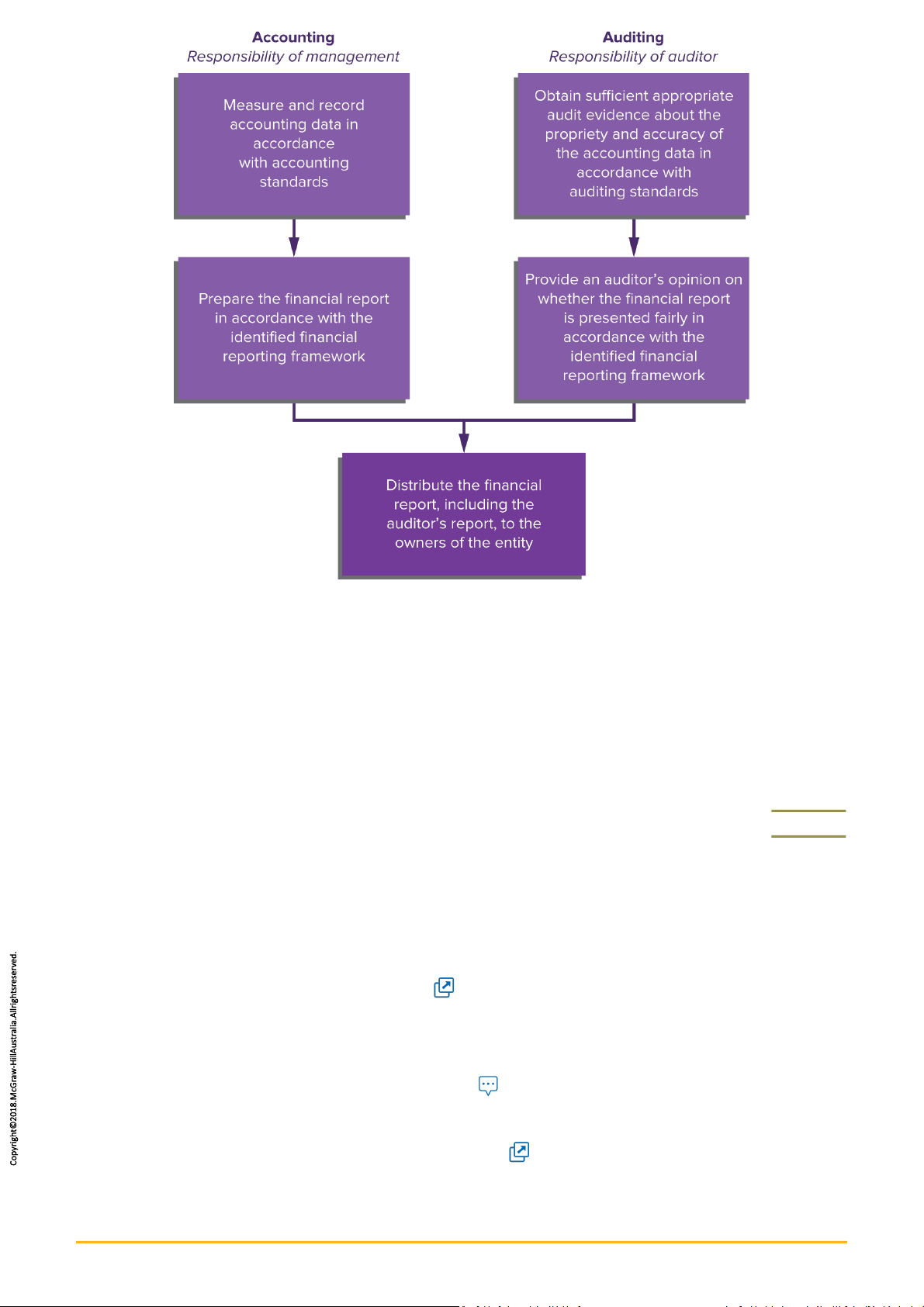

LO 4.1 Accounting and auditing contrasted

As a process, financial report auditing is linked with accounting principles and procedures

used by businesses and other entities. An auditor renders an opinion on the financial

report of an entity. The financial report is the product of the entity’s accounting system

and of judgments made by those charged with the governance and management of the entity.

As indicated by ASA 200.3 (ISA 200.3), the purpose of an audit is to enhance the degree of

confidence of intended users of the financial report. Therefore, the ultimate objective of

the audit process is to present an opinion on the presentation of results of operations for

a given period and on the financial position at the end of this period. To form such a

judgment about the financial report of an entity, the auditor must look behind the

financial report to the data and the allocations of the data.

Therefore, there is a close relationship between accounting and auditing. Auditors work

primarily with accounting data. They attempt to satisfy themselves that the data

summarised in the financial report are the data arising from transactions and events that

the entity actually experienced. Further, they must make judgments about the allocations

of data that have been made by those charged with governance and management, and

decide whether the financial report presentation is appropriate or misleading. To make

these judgments, auditors cannot limit themselves to the records and accounts of the

entity. They must be concerned with the total entity, because non-accounting activities,

including the behaviour of the participants in the entity, influence not only the data but

also the judgments of those charged with governance and management relating to the

accounting for and reporting of the data. The audit function focuses on accounting, and

the auditor must first be a competent accountant, but the audit function also extends

beyond accounting (see Figure 4.2 ). lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

FIGURE 4.2 Relationship between accounting and auditing Professional scepticism

The end product of an accountant’s work is a financial report. The financial report may

simply be the results of this work, or it may be adjusted according to the desires of those

charged with governance and management who might wish to classify and report Page

138 data in particular ways. As indicated by ASA 200.A48 (ISA 200.A48), it is possible to

prepare different financial reports from the same data, because accounting standards

allow a choice between several acceptable accounting methods, and because judgment

will be exercised in determining the amounts for some accounts, such as for various

provisions. Also, as discussed in Chapter 1 , the preparers of the financial reports are

potentially biased, as they have a vested interest in the information contained in the

financial report. Therefore, ASA 200.15 (ISA 200.15) requires the auditor to plan and

perform the audit with professional scepticism , recognising the possible existence of

material misstatements in the financial report. Professional scepticism is critical to the

audit process (see Auditing in the global news 4.1 ). lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

4.1 Auditing in the global news ...

Professional scepticism lies at the heart of a quality audit

In 2015, the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB),

International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA), and the International

Accounting Education Standards Board (IAESB) convened a small, cross-

representational working group—the Professional Scepticism Working Group—to

formulate views on whether and how each of the three

boards’ sets of international standards could further contribute to strengthening the

understanding and application of the concept of professional scepticism as it applies to an audit.

Today, the topic of professional scepticism is featured prominently in each of the

board’s strategic considerations, and all three boards have important initiatives

related to professional scepticism. All three boards see the opportunity for shorter

term actions as well as the need for longer term considerations, in consultation with each other.

The importance of professional scepticism to the public interest is underscored by

the increasing complexity of business and financial reporting, including greater

use of estimates and management judgments, changes in business models

brought about by technological developments, and the fundamental reliance the

public places on reliable financial reporting.

Source: IAASB, IESBA; IAESB (2017) ‘Towards Enhanced Professional Scepticism’, IFAC, August, New

York, p. 3. This text is an extract from ‘Towards Enhanced Professional Scepticism’ Observations of the IAASB-

IAESB-IESBA Professional Skepticism Working Group, published by the International Federation of Accountants

(IFAC) Aug 14, 2017 and is used with permission of IFAC. Such use of IFAC’s copyrighted material in no way

represents an endorsement or promotion by IFAC. Any views or opinions that may be included in Auditing &

Assurance Services in Australia 7e are solely those of McGraw-Hill Education and do not express the views and

opinions of IFAC or any independent standard setting board associated with IFAC.

The Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB) Glossary describes professional

scepticism as ‘an attitude that includes a questioning mind, being alert to conditions

which may indicate possible misstatement due to error or fraud, and a critical assessment of audit evidence’. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

Professional scepticism needs to be exercised throughout the planning and performance

of the audit. ASA 200.A20–A22 (ISA 200.A20–A22) indicate that professional scepticism includes:

questioning the reliability of documents, information and management

explanations being alert to possible contradictory evidence questioning the

sufficiency and appropriateness of audit evidence being alert to conditions

that may indicate risks of fraud critically challenging management judgments, assumptions and estimates.

Further, with the rapid changes in technology in recent years, such as data analytics,

which have not as yet been incorporated into the auditing standards, there is a need for

the auditor to consider whether circumstances exist that indicate a need for audit

procedures Page 139 to be applied in addition to those required by the auditing standards.

Professional scepticism is essentially a mindset. A sceptical mindset drives auditor

behaviour to adopt a questioning approach when considering information and in forming

conclusions. As a result, professional scepticism is linked to the fundamental ethical

principles of objectivity and auditor independence discussed in Chapter 3 and is an

inescapable element in the exercise of professional judgment. Professional judgment

ASA 200.16 (ISA 200.16) requires the auditor to exercise professional judgment in

planning and performing the audit. The AUASB Glossary defines professional judgment as

‘the application of relevant training, knowledge and experience, within the context

provided by auditing, accounting and ethical standards, in making informed decisions

about the courses of action that are appropriate in the circumstances of the audit engagement’.

Further, ASA 200.A25 (ISA 200.A25) emphasises that professional judgment is essential to

conducting an audit, as it is required for decisions such as determining materiality,

assessing audit risk, evaluating audit evidence, assessing the reasonableness of

accounting estimates and evaluating management judgments concerning the application

of the applicable financial reporting framework, including the appropriateness of

accounting treatments and policies and the appropriateness of the going concern basis. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

As indicated by ASA 200.6 (ISA 200.6), the concept of materiality is applied by the auditor

in planning and performing the audit and in evaluating the effect of misstatements on the

financial report. Materiality will be discussed in detail later in this chapter in relation to

planning and in Chapter 11 in relation to completion of the audit. Areas of audit interest

Separating the audit process into understandable parts requires a definition of the areas

of audit interest. The auditor is interested in the accountable activity of the entity; the

organisation of the entity, that is, its organisational structure ; and the risks arising from

its business strategy and the environment in which it operates, that is, its business risk .

Accountable activity of the entity

From an auditing perspective, there are three stages in the accounting process:

1. The collection of original data The original accounting data are exchanges of

consideration between an entity and other entities or individuals. These transactions

take the form of sales of product, purchases of raw materials, purchases of labour,

lending of money, borrowing of money, repaying of money and being repaid. These are

the basic data of accounting and the first and most basic areas of interest to the auditor.

The auditor must understand the flow of transactions through the accounting system.

Therefore, one of the important parts of the audit is a review of the accounting system,

because a substantial part of the effort in an audit is concerned with the operation of that system.

2. The allocations and reclassifications of accounting data Accounting journals are often

called the ‘books of prime entry’, because the first stage of the accounting process

consists of recording the exchange transactions of an entity in a journal. However,

accounting journals also contain entries that do not represent exchange transactions.

These entries are made to allocate and reclassify original exchange data to other

accounts in preparation for placement in the financial report. All the allocations and

reclassifications in an entity’s journals are made according to procedures and practices

that have been developed by accountants over the years. For example, there are both

acceptable and unacceptable ways of depreciating fixed assets, amortising other

longlived assets and allocating labour and materials costs to periods. This part of the

audit depends on the auditor’s knowledge as an accountant. As an accountant, the

auditor knows which allocation and reclassification methods are acceptable, and must

observe what the entity has done and decide whether it has followed acceptable

methods Page 140 and made acceptable choices where judgment is involved. As discussed

earlier, this will involve the auditor applying professional scepticism to client choices, judgments and estimates. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

3. The presentation of the results of the accounting process As discussed in Chapter 1 ,

in order to add credibility to a report, the auditor needs to examine that the subject

matter is prepared in accordance with suitable criteria and provide an assessment to

accompany the report prepared by the responsible party. Hence, in accordance with ASA

700 (ISA 700) and the Corporations Act 2001, in a financial report audit the auditor is

required to report on whether the financial report presents fairly the financial position

and operating results (or gives a true and fair view) in accordance with Australian accounting standards.

There are rules that govern the placement of various items in the financial report and

the terminology used to present them. The auditor must use accounting knowledge, at

the allocation stage, to decide whether the client has properly prepared the financial

report. Further, the auditor must review the accompanying notes to the financial report

and judge their adequacy and completeness. Guidance on these issues is available by

reference to accounting standards and other professional statements and to the

disclosure requirements contained in the Corporations Act 2001. Organisation of the entity

The auditor also has the internal organisational structure of the entity with which to work.

In auditing terminology this is referred to as internal control . The auditor can make

enquiries of client personnel and review the system of documentation used by the entity;

trace various types of transactions from initial to ultimate disposition in the system to

observe its functioning; and, finally, make an evaluation of the system to identify strengths

and weaknesses. These activities are part of the auditor’s evaluation of the controls over

the accounting system. The accuracy and reliability of the accounting system depends on how it is controlled.

The objectives of internal control are linked with the auditor’s concern with the flow of

transactions through the accounting system and the impact of business risk on the entity’s

ability to achieve its objectives. Internal control is designed and implemented to address

identified business risks that threaten the achievement of any of these objectives. Internal

control will be discussed further in Chapter 7 . Business risk

The auditor needs to understand the entity’s business strategy, its business environment

and the risks it faces to determine whether these might affect the financial report.

Auditors use their understanding of the client’s business, industry and risks to develop a lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

more efficient and effective audit. Business risk will be discussed later in this chapter and in detail in Chapter 5 . QUICK REVIEW 1.

Accounting is concerned with measuring and recording data, while auditing

is concerned with obtaining sufficient appropriate evidence as to their propriety and accuracy. 2.

Accounting involves the preparation of the financial report, while auditing

involves giving an opinion on the financial report. 3.

Professional scepticism and the exercise of sound professional judgment are

critical to a high-quality audit. 4.

One key area of audit interest is the accountable activity of the entity, which

includes the collection of original accounting data, the allocation and

reclassification of accounting data and the presentation of the results in the financial report. 5.

A second key area of audit interest is the organisation of the entity, including internal control. 6.

A third key area of audit interest is the entity’s business risk. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Page 141

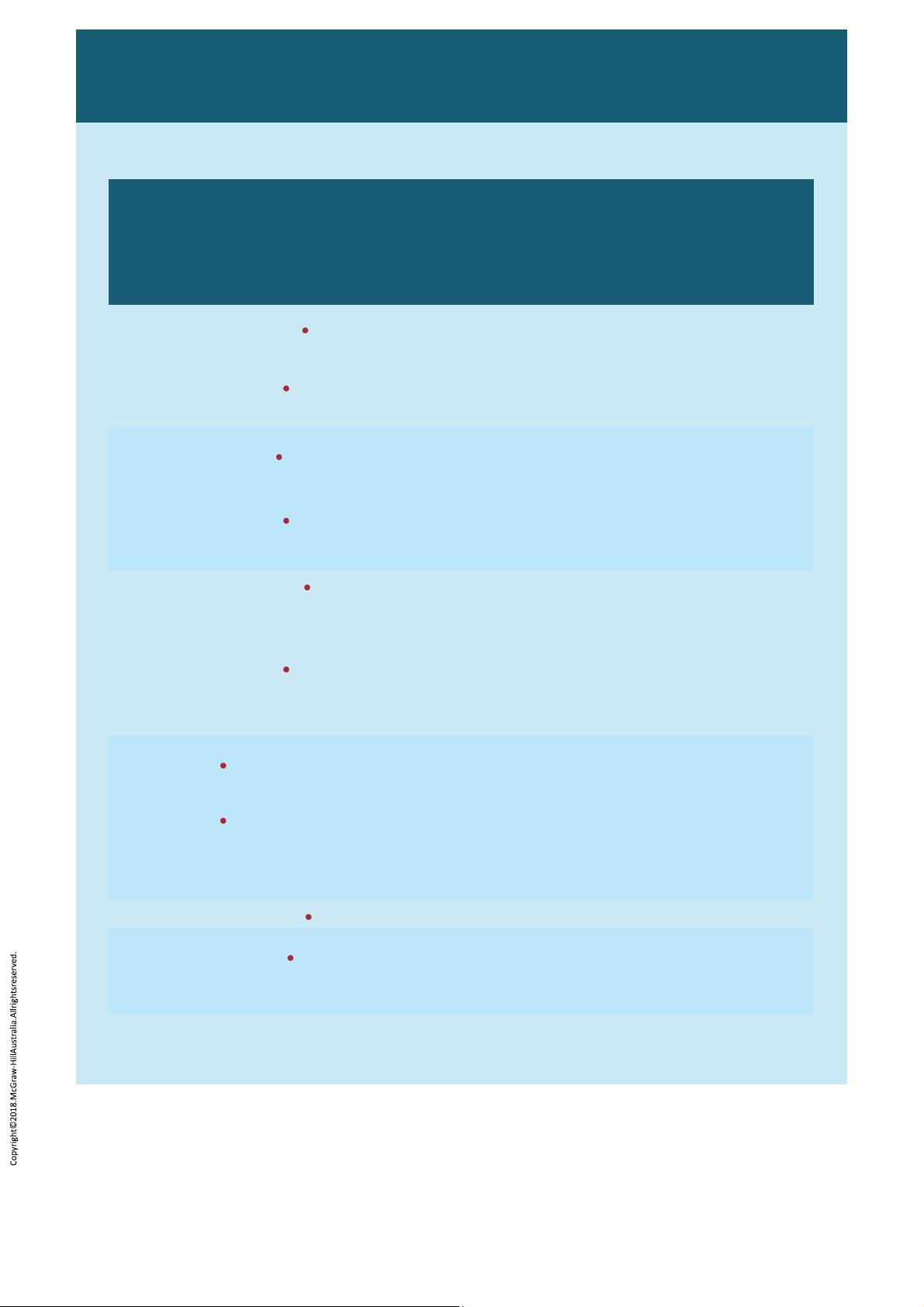

LO 4.2 Financial report assertions and audit objectives and procedures

In effect, by presenting a financial report, those charged with governance and management

are stating certain things about the entity’s financial position and operations. These

assertions by those charged with governance and management that are embodied in the

financial report are referred to as financial report assertions . The auditor uses assertions

to assess risks, by considering the different types of potential misstatements that may occur

and then designing appropriate audit procedures that address these risks. The assertions

deal essentially with recognition and measurement of the various elements of the financial

report and related disclosures. ASA 315 (ISA 315) has two categories of assertions: classes

of transactions and events and related disclosures, and account balances and related

disclosures. These are set out in ASA 315.A128 (ISA 315.A128), as follows in Exhibit 4.1 . lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 EXHIBIT 4.1

TWO CATEGORIES OF FINANCIAL REPORT ASSERTIONS lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

1. Assertions about classes of transactions and events, and related disclosures, for the period under audit (a)

Occurrence —transactions and events that have been recorded or

disclosed have occurred and pertain to the entity. (b)

Completeness —all transactions and events that should have been

recorded have been recorded and all related disclosures that should have

been included in the financial report have been included. (c)

Accuracy —amounts and other data relating to recorded transactions and

events have been recorded appropriately and related disclosures have been

appropriately measured and described. (d)

Cut-off —transactions and events have been recorded in the correct accounting period. (e)

Classification —transactions and events have been recorded in the proper accounts. (f)

Presentation —transactions and events are appropriately aggregated or

disaggregated and clearly described, and related disclosures are relevant and understandable.

2. Assertions about account balances, and related disclosures, at the period end (a)

Existence —assets, liabilities and equity interests exist. (b)

Rights and obligations —the entity holds or controls the rights to assets,

and liabilities are the obligations of the entity. (c)

Completeness —all assets, liabilities and equity interests that should have

been recorded have been recorded, and all related disclosures that should

have been included in the financial report have been included. (d)

Accuracy, valuation and allocation —assets, liabilities and equity

interests are included in the financial report at appropriate amounts and

any resulting valuation or allocation adjustments are appropriately

recorded, and related disclosures have been appropriately measured and described. (e)

Classification —assets, liabilities and equity interests have been recorded in the proper accounts. (f)

Presentation —assets, liabilities and equity interests are appropriately lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

aggregated or disaggregated and clearly described, and related disclosures

are relevant and understandable.

Source: Extracted from Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB), 2015 ASA 315

Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and Its lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

Environment. (c) 2018 Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB). The text, graphics and layout of this

publication are protected by Australian copyright law and the comparable law of other countries. No part of the

publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written

permission of the AUASB except as permitted by law. For reproduction or publication permission should be sought

in writing from the Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. Requests in the first instance should be addressed to

the Technical Director, Auditing and Assurance Standards Board, PO Box 204, Collins Street West, Melbourne, Victoria, 8007.

The auditor needs to obtain evidence that supports each of the assertions for every

material component of the financial report. A component of the financial report may be

an account balance (or group of account balances), a class of transactions or a disclosure.

The categories of assertions provide a framework for developing specific audit Page 142

objectives for each material account balance, class of transactions or disclosure. An audit

objective is an assertion translated into terms that are specific to the particular balance

or class of transactions, the entity’s circumstances, the nature of its economic activity

and the accounting practices of its industry. Consider Global example 4.1 , which

shows some specific audit objectives. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

GLOBAL EXAMPLE 4.1 Assertions and objectives for the account balance of

inventory of a manufacturing company Financial report assertion Illustrative audit objectives Existence

Inventories included in the statement of financial position physically exist.

Inventories represent items held for sale in the normal course of business. Rights and

The company has legal title or similar rights of ownership obligations to the inventories.

Inventories exclude items billed to customers or owned by others. Completeness

Inventory quantities as per the accounting records

include all products, materials and supplies owned by the company that are on hand.

Inventory quantities include all products, materials and

supplies owned by the company that are in transit or stored at outside locations. Accuracy,

Inventories are properly stated at the lower of cost and valuation and net realisable value. allocation

Slow-moving, excess, defective and obsolete items

included in inventories are properly identified and valued. Classification

Inventory costs are recorded in the correct accounts. Presentation

Accounting policy for inventory is clearly described in the financial report.

A number of accounting pronouncements now contain complex measurement and

disclosure provisions based on fair value, which need to be considered by the auditor. For

example, ASA 540 (ISA 540) Auditing Accounting Estimates, Including Fair Value

Accounting Estimates and Related Disclosures addresses audit considerations relating to

the valuation and allocation, accuracy, presentation and disclosure of material financial lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

report items presented or disclosed at fair value. These include understanding the entity’s

process for determining fair value, assessing its appropriateness and considering the use of an expert. QUICK REVIEW

1. Those charged with governance and management make assertions about the

entity’s financial position and operations, and these are embodied in the financial report.

2. The auditor obtains evidence to support these assertions for material

components of the financial report. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

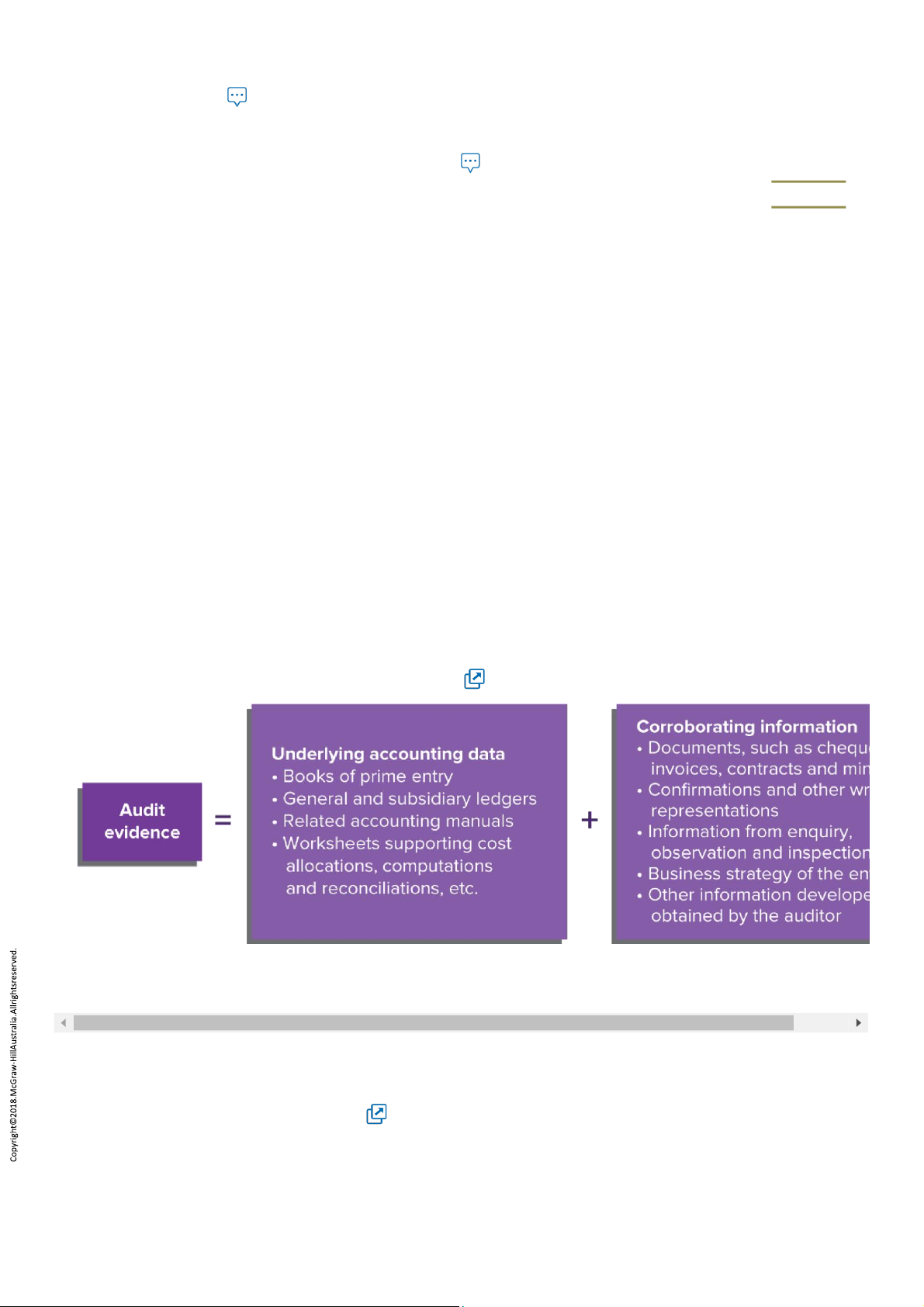

LO 4.3 Audit procedures and evidence

Audit procedures are the actions that an auditor takes in acquiring evidence. The

procedures are not evidence in themselves; they are the means of acquiring evidence.

ASA 500.5 (ISA 500.5) defines audit evidence as all of the information used by the

auditor in arriving at the conclusions on which the auditor’s opinion is based. It includes

Page 143 all the data and information underlying the financial report and

corroborating information. Audit evidence includes evidence obtained from audit

procedures performed during the audit and may also include evidence obtained from

other sources, such as previous audits. However, ASA 500.A11 (ISA 500.A11) states that

where evidence from a prior audit is used the auditor must perform audit procedures to

ensure its continuing relevance.

The audit equation can be expressed as:

audit evidence = underlying accounting data + corroborating information

The auditor needs to test the propriety and accuracy of the underlying accounting data in

order to be able to express an opinion on the financial report. However, some

corroborating information for material assertions within the financial report is essential.

This audit equation is illustrated in Figure 4.3 .

FIGURE 4.3 The audit equation

The use of audit procedures to obtain evidence to corroborate accounting data can be

illustrated by focusing on one type of transaction. Consider the diagram of a cash

purchase transaction in Figure 4.4 . The auditor may inspect the documentary evidence

in the entity’s records. The item received is recorded as an increase in inventory. A copy of

the purchase order is sent to the supplier and a receiving report is prepared to indicate

receipt of the merchandise. The item given up is recorded as a cash reduction, and there