Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Page 89 CHAPTER 3

Ethics, independence and corporate governance

LEARNING OBJECTIVES (LO) 3.1

Explain the nature and importance of professional ethics, and describe the

three main categories of ethical theory.

3.2Outline the essence of the accounting bodies’ code of ethics.

3.3Apply sound ethical decision-making techniques.

3.4Explain the concept and importance of auditor independence.

3.5Explain fee determination.

3.6Explain the concept of corporate governance. RELEVANT GUIDANCE ASA 102

Compliance with Ethical Requirements when Performing Audits,

Reviews and Other Assurance Engagements ASA 200/ISA 200

Overall Objectives of the Independent Auditor and the

Conduct of an Audit in Accordance with Australian

(International) Auditing Standards ASQC 1/ISQC 1

Quality Control for Firms that Perform Audits and Reviews of

Financial Reports and Other Financial Information, Other

Assurance Engagements and Related Services Engagements

Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants APES 110/IFAC

Quality Control for Firms APES 320 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 CHAPTER OUTLINE

As discussed in Chapters 1 and 2 , the auditor is a member of a timehonoured

profession, and the status of the profession and the responsibilities that accompany this

status affect the audit and assurance services function and the structure of the profession.

The independent auditor is subject to regulation imposed by the profession and by society

in general. The imposition of ethical standards on members by a profession is one aspect of this regulation.

This chapter outlines the nature and importance of ethics, and the responsibilities

imposed on auditors by the profession through the code of professional ethics. One

fundamental ethical requirement for an auditor is independence. This chapter explains

the concept of independence and how it is supported by legislation and the ethical rules.

The major threats to auditor independence are explained. Also discussed is the concept

of corporate governance and the part played by audit committees in this function.

How this chapter fits into the overall auditing and assurance profession is illustrated in

Figure 3.1 , which is an expansion of part of the overall flowchart provided in Chapter 1 .

FIGURE 3.1 Flowchart of auditing and assurance profession Page 90

LO 3.1 Professional ethics and ethical theory lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

The nature and importance of professional ethics

Ethics are concerned with the requirements for the general wellbeing, prosperity,

health and happiness of people, and with things that promote or prevent them.

Paragraph 3(f) of the Supplemental Royal Charter of Chartered Accountants Australia and

New Zealand (Chartered Accountants ANZ) states that one of its principal objects is to do

all things that may advance the profession of accountancy, whether in relation to the

practices of public accountants or in relation to industry, commerce, education or the

public service. Similarly, paragraph 3(1) of the constitution of CPA Australia establishes

one of its objects as protecting, supporting and advancing the status, character and

interests of the accountancy profession generally. The Institute of Public Accountants (IPA)

has similar objectives. Community wellbeing includes the flourishing of business and

industry. The objectives of the accounting bodies support an environment of personal and

corporate integrity that promotes community wellbeing. This necessarily involves defining

what is right and what is wrong.

Chartered Accountants ANZ’s Royal Charter, CPA Australia’s constitution and the IPA’s

constitution give these bodies the power to prescribe high standards of practice and

professional conduct for their members, and to prescribe disciplinary procedures and sanctions.

In practice, ethics require both knowledge of moral principles and skill in applying them to

problems and decisions. In addition, sound ethical practice presupposes the development

in individuals and society of the virtues or good habits that ensure the moral health of the community.

Establishing codes of ethics and disciplinary rules does not necessarily create an ethical

culture in an organisation or business, nor does it ensure the moral integrity of its

individual members. It is necessary to promote not only competence in ethics but also the

personal qualities of responsibility and moral conscientiousness. Codes of ethics, rules,

regulations and laws do not have meaning or moral legitimacy in themselves. Rather, their

authority and legitimacy depend on whether they are perceived as helping to promote

people’s wellbeing. If rules are considered to be unjust, discriminatory or oppressive,

people are likely to disregard them or demand they be changed. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

APES 110 indicates that the Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants does not Page

91 cover all aspects of ethical conduct and that members are expected to comply with the

spirit as well as the letter of the rules. They recognise that ethics are principally attitudes

of mind rather than compliance with written rules of conduct.

Society is governed by rules, regulations and laws. From an auditing viewpoint, this tends

to place the focus on ‘black letter’ law. However, it needs to be remembered that it is

always possible to question whether a rule is a good rule. Value judgments need to be

made as to whether rules are fair, whether they respect the rights of all parties and

whether they protect those parties who are unable to defend their rights. Sound statutory

law must be based on and consistent with common law and natural justice if it is to promote human wellbeing. Ethical theory

There are three main categories of ethical theory that will be discussed in this chapter:

teleological ethics, deontological ethics and virtue ethics. Teleological ethics

Teleological ethics are also called consequential ethics because they deal with the

consequences or outcomes of actions. Generally, if the benefits of a proposed action

outweigh the costs, then the decision is considered morally correct. The most important

theory of teleological ethics is utilitarianism.

Jeremy Bentham (1784–1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806–73) are generally acknowledged

as having developed the theory of utilitarianism , which states that ethical decision

making should maximise the greatest good for the greatest number. This involves an

assessment of costs and benefits, not only in economic terms but also in terms of human

costs and benefits. Therefore, it involves a value judgment and needs to consider all the

stakeholders who will be affected by a decision. The outcomes are measured both in

economic terms and in psychological terms, such as pain and happiness. Therefore,

measuring and assigning a numeric value to the consequences of an action is often difficult. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Deontological ethics

Deontological ethics are based on duties and rights. Duties are obligations and are

actions that a person is expected to perform, while rights are entitlements and are actions

that a person expects of others. These duties and rights are set down in rules that must

be followed regardless of the consequences. Hence, deontological ethics are also

sometimes called non-consequential ethics. Deontological ethics are particularly

important to auditors in understanding their duties based on the ethical rules of the accounting bodies.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) placed high value on personal rights and personal moral

autonomy, and the basis of his ethical theory was the principle of respect for persons. This

acknowledges the intrinsic value of all persons and recognises that we should not use

people to achieve our own ends. Further, we should recognise a duty of care to others, as

expressed in the golden rule or principle of reciprocity: ‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you’.

This rule leads to the principle of beneficence, which advocates that we should do good to

others rather than harm. Kant suggested the categorical imperative as a universal ethical

law. This means that, when considering the validity of a rule, we need to consider

whether we would be happy to have this action applied in all similar circumstances

regardless of the consequences. This leads to the need for the principle of justice.

John Rawls (1957) argued that the fundamental idea underlying the concept of justice is

that of fairness. He argued that there are two principles that serve as the basis of justice and fairness:

The first principle is that each person participating in a practice, or

affected by it, has an equal right to the most extensive liberty

compatible with a like liberty for all; and the second is that

inequalities are arbitrary unless it is reasonable to expect that

they will work out for everyone’s advantage and unless the offices

to which they attach, or from which they may be gained, are open to all.

Thus, Rawls argued that ethical rules should seek equality and the maximum Page 92

degree of liberty that does not conflict with the liberty of others or increase inequalities or disadvantage to others. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Virtue ethics

Virtue ethics , which date back to Aristotle, are concerned primarily with integrity,

which is an essential characteristic of an auditor. Virtue ethics focus on the person

undertaking the action. Virtues are personal qualities that enable us to do what is

ethically desirable, and generally include traits of character such as courage, fairness,

honesty, integrity, loyalty, courtesy and fidelity. Virtue ethics emphasise what makes up a

morally good person, but do not necessarily make it clearer what should be done to solve an ethical conflict.

The relevance of these three ethical theories to the accounting bodies’ code of ethics and

to ethical decision making by auditors will be discussed later in this chapter. QUICK REVIEW

1. The accounting bodies require their members to behave ethically.

2. Behaving ethically requires knowledge of moral principles and decisionmaking skills.

3. Teleological ethics are based on ethical outcomes.

4. Deontological ethics are based on ethical duties and rights.

5. Virtue ethics are based on personal ethical qualities.

LO 3.2 Accounting bodies’ code of ethics

APES 110 Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants sets out the main ethical pronounc

ements for members of Chartered Accountants ANZ, CPA Australia and the IPA. ASA

200.14 (ISA 200.14) requires that auditors comply with relevant ethical requirements.

Further, ASA 102.5 and A1–A7 specifically require the auditor to comply with APES 110.

The code consists of the following three sections:

1. Part A: General Application of the Code Sections 100–150 set out the fundamental

principles of professional ethics and provide a conceptual framework for applying these principles.

2. Part B: Members in Public Practice Sections 200–291 illustrate how the conceptual

framework is to be applied to specific situations in public practice. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

3. Part C: Members in Business Sections 300–350 illustrate how the conceptual framework

is to be applied to specific situations in business.

The ethical rules play an important part in an auditor’s behaviour. The written code of

appropriate professional conduct is designed to enable members to arrive at the proper

conclusion when making ethical decisions. As a result, the ethical rules comment upon

different types of relationships faced by auditors and spell out some of the auditor’s

responsibilities. The preface to APES 110 states that compliance with the code is mandatory for all members.

There are also a number of APES standards, not all of which are relevant to auditors but

which are mandatory for members of the three accounting bodies. In general, these

statements seek to promote the fundamental principle of ‘competence’.

The APES 200 series is applicable to all members of the accounting bodies and includes: APES 205

Conformity with Accounting Standards APES 210

Conformity with Auditing and Assurance Standards APES 215

Forensic Accounting Services APES 220 Taxation Services APES 225 Valuation Services APES 230

Financial Planning Services. Page 93

The APES 300 series is applicable to members of the accounting bodies in public practice and includes: APES 305 Terms of Engagement APES

Dealing with Client Monies 310 APES

Compilation of Financial Information 315 APES

Quality Control for Firms 320 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 APES

Risk Management for Firms 325 APES Insolvency Services 330 APES

Reporting on Prospective Financial Information Included in a 345 Disclosure Document APES

Participation by Members in Public Practice in Due Diligence 350

Committees in Connection with a Public Document

The purpose of the code of ethics

A code of ethics is a formal and systematic statement of rules, principles, regulations or

laws developed by a community to promote its wellbeing and to exclude or punish any

undermining behaviour. Therefore, a code of ethics may serve several purposes. It may:

make explicit those values that may be implicitly required (for example, the underlying

core values or principles in sections 100–150 of APES 110, which are discussed later in this chapter)

indicate how members should act towards one another (for example, the responsibilities

to professional colleagues exhibited through the protocol to be followed when superseding

another auditor (section 210 of APES 110) and permissible forms of advertising (section

250 of APES 110), both of which are discussed in Chapter 5 .) provide an objective

basis for sanctions against people who violate the rules (for example, disciplinary action

under Chartered Accountants ANZ’s Supplemental Royal Charter,

CPA Australia’s constitution and the IPA’s constitution, discussed in Chapter 2 , or by

the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC)). A member’s behaviour

can be judged, in part, by reference to the rules laid down in APES 110. An established

code of ethics is one mechanism of self-regulation.

In addition, APES 110 communicates the profession’s responsible attitude of

accountability to the community at large.

Like many professional codes, the ethical rules of the accounting bodies endeavour to

promote standards of competence, proficiency and personal moral integrity in their

members. These qualities are similar to those that Thomson et al. (1976) referred to as

Aristotle’s intellectual and moral virtues. Aristotle’s intellectual virtues included science lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

(knowledge), techne (practical skill and competence, intelligence, judgment,

understanding, persistence and resourcefulness) and wisdom. His moral virtues included

courage (loyalty and integrity), temperance (discipline, friendliness, generosity,

magnanimity, communication and social skills) and justice. Thomson et al. indicated that

these virtues can be depicted as an arch, with intellectual values on one side and moral

virtues on the other. The keystone holding them together is the virtue of prudence or acquired practical wisdom.

However, written codes of conduct should not be viewed as the panacea for the

profession’s ethical problems. As mentioned previously, these codes do not by themselves make people behave ethically. The virtues of an auditor

In line with the discussion of the professional status of an auditor in Chapter 2 , APES

110 section 100.1 states that a distinguishing mark of the audit profession is its

acceptance of the responsibility to act in the public interest . The public interest is

defined as the collective wellbeing of the community of people that the members serve.

Therefore, the auditing profession’s ‘public’ consists of clients, credit providers,

governments, employers, employees, investors, the business and financial community

and others who rely on the objectivity and integrity of the auditor. The public interest

principle recognises that conflicts occur between the various stakeholder interests and

that when such conflicts occur, the auditor’s primary responsibility is to the public

interest, not to himself or herself or to the client. Rather, the auditor is required to

advance the interests of their Page 94 client, provided that it does not conflict with the

obligation to safeguard the public interest.

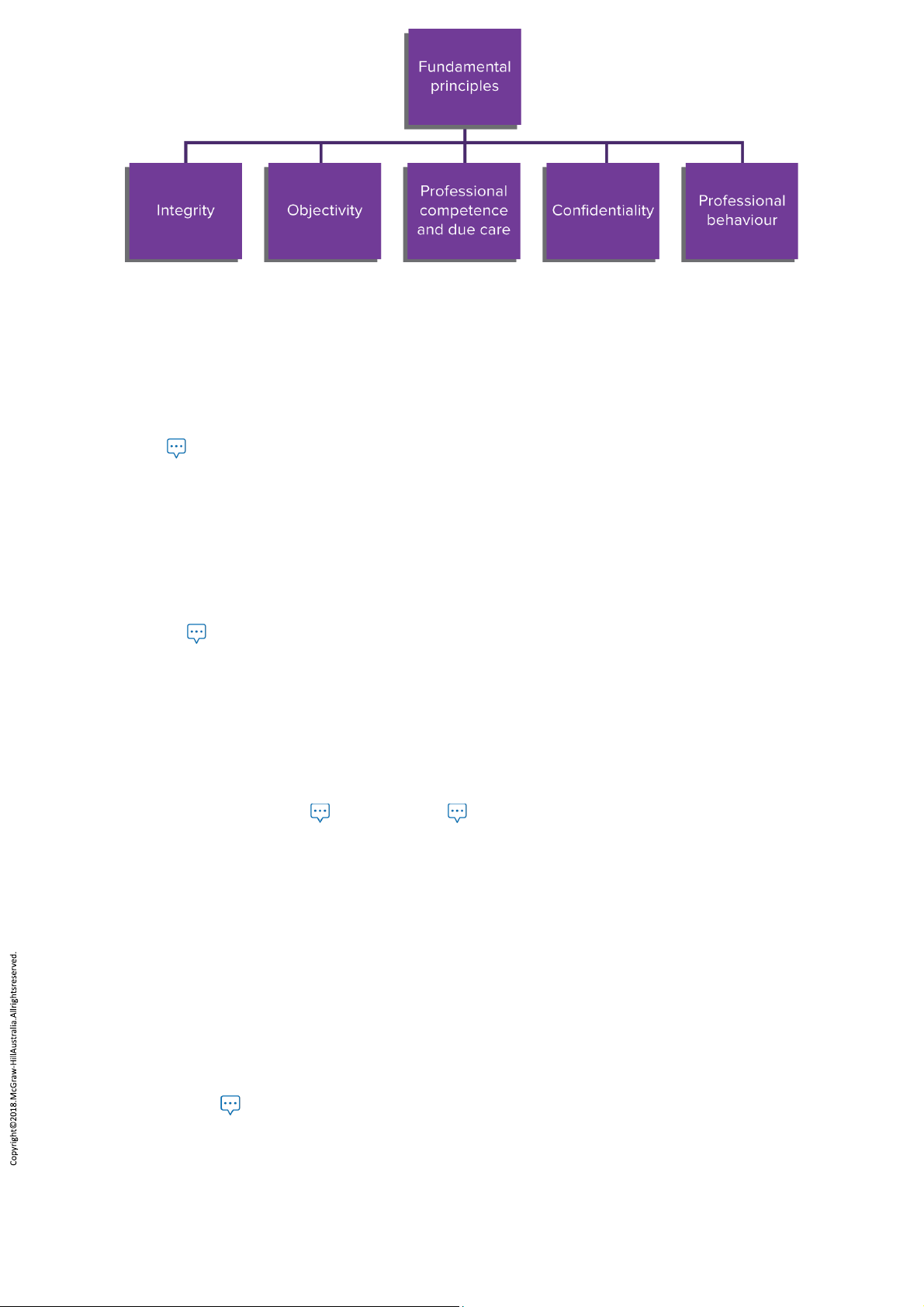

Further to the discussion in Chapters 1 and 2 regarding the fundamental ethical

principles that an auditor must follow, APES 110 section 100.5 sets out the following five

fundamental principles, shown in Figure 3.2 , that apply to all members. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

FIGURE 3.2 Fundamental principles

These fundamental principles are discussed in more detail in sections 110–150 of APES 110:

1. Integrity Auditors should act with consistency, treating like cases in a like manner.

Honesty is an integral part of this value. The principle of integrity therefore imposes an

obligation on an auditor to be straightforward and honest in all professional and

business relationships and requires fair dealing and truthfulness. As a result, in

accordance with APES 110 section 110.2, an auditor should not be associated with any

reports or other communications that are false, misleading or recklessly prepared.

Integrity is supported by the ethical principle of respect for persons.

2. Objectivity In accordance with APES 110 section 120, auditors must be fair and must

not allow bias, conflict of interest or the undue influence of others to override their

objectivity. They need to maintain an impartial attitude and not represent vested

interests when auditing a financial report. Therefore, relationships that bias or unduly

influence the auditor’s professional judgment should be avoided. As fairness is an

important behavioural implication of this value, objectivity can be justified by the ethical principle of justice.

3. Professional competence and due care Section 130.1 of APES 110 indicates that

auditors have a duty to attain and maintain their level of professional competence and

should only undertake work that they can expect to complete with professional

competence and due care in accordance with applicable technical and professional

standards. Auditors have a duty to maintain their level of competence throughout their

professional career through continuing professional development. Clearly, a client’s

interests cannot be adequately served by auditors who do not possess the necessary

skills for the tasks that they undertake. This requires appropriate training and

supervision. Accepting work for which the auditor is not competent could lead to

damage to the client. The maintenance of high standards of technical proficiency is

designed to protect clients, and so the value of competence and due care is supported

by the ethical principle of beneficence.

4. Confidentiality Auditors hold positions of trust and have access to many valuable and

private pieces of information in the course of their work. Section 140.1 of APES 110

indicates that they should respect the confidentiality of information obtained during the lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

course of their work and should not disclose such information to a third party without

authority or unless there is a legal or professional duty that is not prohibited by law to

do so, as outlined in section 140.7. However, as discussed in Auditing in the global news

3.1 , as a result of international developments and amendments to APES 110 in

September 2017, to include a new section 225, ‘Responding to non-compliance with

laws and regulations’ (NOCLAR), auditors now need to consider their reporting Page 95

obligations if they uncover or suspect illegal acts such as fraud, corruption, bribery or

money laundering during the course of their professional work. APES 110 now permits

accountants to set aside the principle of confidentiality where such illegal acts are

suspected. Where an auditor is considering disclosing confidential information of a

client without the client’s consent, on the basis that that disclosure is required by law or

professional requirements, they are strongly advised under section AUST 140.7.1 to first

obtain legal advice. This duty to protect the interests of clients means that

confidentiality reflects the ethical principle of beneficence.

5. Professional behaviour Section 150.1 of APES 110 indicates that auditors should

comply with relevant legislation and conduct themselves in a manner consistent with

the good reputation of their profession and refrain from any conduct that could bring

discredit to it. A good reputation is fundamental to the ability of the profession to

continue to enjoy its rights and privileges. Therefore, in addition to their duty to the

public interest and to their clients, auditors have a duty to the profession and must act

in a way that promotes the good reputation of the profession. Section 150.2 of APES 110

indicates that in marketing and promoting themselves auditors must not bring the

profession into disrepute by making exaggerated claims or by disparaging competitors.

Consequently, the value of professional behaviour can be justified by reference to the

ethical principles of beneficence and respect for persons.

3.1 Auditing in the global news ... lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

Confidentiality not a cover for illegal acts

A new standard issued today requires accountants to consider their obligations if

they uncover or suspect illegal acts such as fraud, corruption, bribery or money

laundering during the course of their professional work.

The ground-breaking standard in Australia adopts the new international approach

and permits accountants to set aside the principle of confidentiality where illegal acts are suspected.

‘This standard encourages professional accountants to speak up where they

discover laws and regulations are not being adhered to—and identifies a process to

go through enabling accountants to raise concerns appropriately without

breaching other professional and ethical standards,’ APESB Chair, The Honorable Nicola Roxon, said.

‘It is feared that, in the past, identifying potential illegal acts and raising the alarm

did not always prevail over confidentiality and other obligations to a client or employer.’

The new standard, Responding to Non-Compliance with Laws and

Regulations (NOCLAR), comes into force on 1 January 2018—allowing time for

accountants to update their systems to comply with the standard. Individual firms

and accountants are urged to adopt this standard earlier where possible to meet international best practice.

The new standard will be incorporated into the Australian code APES 110 Code of

Ethics for Professional Accountants …

Source: Text extract from Media Release 30 May 2017.

Reproduced with the permission of the copyright owner, Accounting Professional & Ethical Standards Board Limited (APESB), Australia.

Further, as will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter, section 290 of APES 110

provides specific guidance on independence requirements for audit and review

engagements, while section 291 provides similar requirements for other assurance

engagements. Auditors should both be, and appear to be, free of any interest which might lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

be regarded as incompatible with objectivity and integrity. Without independence, the

auditor’s opinion is worthless. Independence, however, can be easily compromised.

Objectivity, independence and technical standards equate with Aristotle’s Page 96

intellectual virtues. Honesty, integrity, confidentiality and ethical behaviour equate with

Aristotle’s moral virtues. Professional competence equates with what Aristotle called

prudence, or the practical wisdom necessary to apply abstract general principles to specific situations.

Auditors are both legally and morally accountable to their clients. Therefore, competence

in ethics is an important requirement of a good auditor. QUICK REVIEW

1. The ethical rules required to be followed by members of the accounting bodies

provide important guidance to members.

2. Ethical rules cannot cover all aspects of ethical conduct.

3. Ethics are principally attitudes of mind.

4. The key ethical principles of the accounting bodies are public interest, integrity,

objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality and

professional behaviour. In addition, independence is required for assurance engagements. LO 3.3 Applying ethics

Sound ethical practice requires responsible people with a critical understanding of sound

decision making based on fundamental ethical principles. This requires:

knowledge of the basic principles on which moral values and rules are based

competence in decision-making skills ability to choose appropriate policies and

decision procedures in different situations.

To act ethically is to act appropriately and responsibly in different situations, providing a

clear, coherent and reasoned justification for decisions and actions, based on commonly accepted values or standards. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

An auditor needs to combine ethical rules with skills in making decisions and setting

policies. As indicated by Leung and Cooper (1995, p. 32):

The complexity of the different ethical problems encountered by

accountants requires not only a good knowledge of a set of ethical

principles, but also the skills and competence to handle conflicting

roles and interests relating to accountancy practice.

Ethical decision-making models

A number of ethical decision-making models have been developed to assist in sound

ethical decision making, such as the American Accounting Association (AAA) model, the

Mary Guy model, the Laura Nash model and the Spiral model. As the basic steps in

problem solving are the same, the various ethical decision-making models have many

common features. The most widely used is the AAA model, where each case is analysed

using a seven-step model, shown in Exhibit 3.1 . However, these models should not be

followed slavishly but rather used as a framework for decision making, as indicated in

APES 110 section 100.18, which states that the key factors to be considered in ethical conflict resolution are: relevant facts ethical issues involved

fundamental principles related to the matter in

question established internal procedures alternative courses of action. Page 97 EXHIBIT 3.1

AMERICAN ACCOUNTING ASSOCIATION MODEL lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 1. Determine the facts What? Who? Where? When? How?

What do we know or need to know that will help define the problem?

2. Define the ethical issues

List the significant stakeholders. Define the ethical issues.

3. Identify the major principles, rules and values

(For example, integrity, quality, respect for persons, profit)

4. Specify the alternatives

List the major alternative courses of action, including those that represent some

form of compromise or point between simply doing or not doing something.

5. Compare values and alternatives—see if clear decision

Determine whether there is one principle or value, or a combination, which is so

compelling that the proper alternative is clear.

6. Assess the consequences

Identify the short-term and long-term, positive and negative consequences for the

major alternatives. The common short-term focus on gain or loss needs to be

measured against the long-term considerations. This step will often reveal an

unanticipated result of major importance. 7. Make your decision

Balance the consequences against your primary principles or values and select the alternative that best fits.

Source: Langenderfer, H. Q., & Rockness, J. W. (1989). Integrating ethics into the accounting curriculum: issues,

problems, and solutions. Issues in Accounting Education. Spring, 58–69.

Ethical decision making also involves consideration of the three aspects of moral theory

discussed earlier in this chapter:

1. Fundamental principles and rules or rights and duties Deontological ethics focus on

the principles and causes, intentions and motives to be considered prior to action.

Fundamental ethical principles include the principle of beneficence (duty to do good to

or protect others), the principle of justice (duty to treat all people fairly) and the

principle of respect for persons (duty to respect the rights of other people). In an ethical

decisionmaking model this involves specifying the facts, including the stakeholders

involved, and identifying the ethical principles and the rights and duties of all parties.

2. Means, methods and the role of the agent Virtue ethics focus on the moral character of

the agent. The integrity and competence of the agent (auditor) are vital to their capacity

to act ethically. In an ethical decision-making model this involves identifying all the lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

options available, considering possible outcomes and knowing the right means to

achieve your goals, based on intellectual and moral virtues.

3. Ends or consequences Teleological ethics focus on the consequences of actions and

their outcomes relative to goals. If the ultimate end of human life is happiness, this

approach can translate into the utilitarian rule of always acting so that your action brings

the greatest amount of happiness to the greatest number of people. However, this must

be balanced by considering the rights of minorities. An assessment of the costs and

benefits for all stakeholders is required. In an ethical decision-making model this

involves the assessment of results in terms of achieving both short-term and long-term goals. Page 98 QUICK REVIEW

1. An auditor needs to combine knowledge of ethical rules with skills in ethical decision making.

2. There are several ethical decision-making models that can assist by providing a

framework for decision making.

3. The most commonly used ethical decision-making model is the American

Accounting Association model.

LO 3.4 Auditor independence

As mentioned earlier, for an audit or other assurance service to add credibility to a

financial report or other subject matter, an auditor needs to remain independent. Auditor

independence is critical to the orderly function of the capital markets, as it helps to build

the trust of various stakeholders in the financial information that has been audited. In

Australia, the requirement of independence for auditors has been reinforced through the

Corporations Act 2001 and the ethical rules of the accounting bodies.

Developments in auditor independence Ramsay Report

Interest in the issue of audit independence was increased by speculation about what role,

if any, audit independence matters played in a number of high-profile corporate failures

during the first half of 2001. As a result, the federal government commissioned a report

by Professor Ian Ramsay on audit independence in Australia. The Ramsay Report, which

was issued in October 2001, examined Australia’s existing legislative and professional

requirements on the independence of company auditors and compared them with lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

equivalent overseas requirements. Where appropriate, the report proposed measures for

strengthening the Australian requirements.

The recommendations covered five key issues concerned either directly with audit

independence (employment relationships, financial relationships and provision of

nonaudit services) or with matters designed to enhance audit independence (audit

committees and a board to oversee audit independence issues). These issues will be

discussed later in this chapter.

The Ramsay Report recommendations envisaged the continuation of the existing

coregulatory regime under which some requirements are included in the corporations

legislation and others are in the ethical rules of the professional accounting bodies. The

federal government included many of the Ramsay Report recommendations in its CLERP 9

amendments to the Corporations Act 2001. The accounting bodies have likewise included

many of the Ramsay Report recommendations in their Code of Ethics for Professional

Accountants (APES 110). IFAC independence rules

In addition, there have been a number of developments internationally, including the

release of new ethical rules by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) in its

Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants in November 2001. IFAC has adopted a

conceptual approach to independence that uses a framework built on principles for

identifying, evaluating and responding to threats to independence. As discussed in

Chapter 2 , international ethical standards are now issued by the International Ethics

Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA). These ethical provisions have been subject to

several revisions since their first issue. APES 110

APES 110, which was first issued in June 2006, is based on the IFAC ethical rules, is tailored

to reflect Australian community expectations and takes into account the CLERP 9

amendments to the Corporations Act 2001. The independence requirements of APES 110

are discussed in detail later in this section. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

Sarbanes–Oxley Act 2002 Page 99

In the US, in response to the collapse of Enron, WorldCom and other high-profile

businesses, the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 provides more stringent independence

requirements and more severe penalties for breaches. Among other things, it restricts

greatly the ability of auditors to provide non-audit services, mandates audit partner

rotation and strengthens the role of the audit committee.

The Sarbanes–Oxley Act 2002 affects not only US companies and US auditors, but any

audit firm actively working as an auditor of, or for, a publicly traded US company or its

subsidiary. Therefore, the Act covers any Australian audit firm that does the audit of a

subsidiary of a US-listed company or that of an Australian company that is listed on a US

stock exchange. During 2004, KPMG admitted providing non-audit services to National

Australia Bank in breach of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rules, after

five staff were seconded to the bank. Even though this was permitted under Australian

rules, KPMG was required to step down as auditor of this client.

Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit

Due to the major corporate collapses both within Australia and overseas, the Joint

Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) resolved to review independent

auditing by registered company auditors. The committee issued its recommendations in

August 2002 in Report 391. Many of the Committee’s recommendations were consistent

with the Ramsay Report and many have been incorporated in the CLERP 9 amendments. HIH Royal Commission

The major companies in the HIH Insurance Group were placed in provisional liquidation

on 15 March 2001. The deficiency of the group was estimated to be between $3.6 billion

and $5.3 billion. On 16 April 2003, the HIH Royal Commission issued its report, The Failure

of HIH Insurance, which contained 61 policy recommendations by Justice Owen, covering

corporate governance, financial reporting, auditing and regulation of the insurance industry. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

Corporate Law Economic Reform Program

In September 2002, the federal government issued a policy paper, CLERP 9, as part of its

Corporate Law Economic Reform Program, seeking stakeholder comments on proposals

for legislative amendments. The paper reviewed, among other things, auditor

independence. Following much discussion, stakeholder feedback, political debate and

some amendments, the Corporate Law Economic Reform Program (Audit Reform and

Corporate Disclosure) Act 2004 was passed by the Senate on 25 June 2004 and received

Royal Assent on 30 June 2004. The CLERP 9 legislation amends a number of Acts,

including the Corporations Act 2001. Some of the most significant changes introduced by

the CLERP 9 amendments are to auditor appointment, independence and rotation

requirements, which are discussed below. Legislative requirements

The Corporations Act 2001 has always contained some provisions which give formal

recognition to the need for auditor independence. The CLERP 9 amendments created a

general duty for the auditor to be independent and avoid conflicts of interest and to

provide a written declaration to directors confirming compliance with the auditor

independence requirements of the Corporations Act 2001. Other key provisions introduced through

CLERP 9 relate to restrictions on auditors being employed by an audit client, additional

specific requirements for appointment as an auditor, audit partner rotation for listed

companies and disclosure of non-audit services. The existing provisions relating to auditor

resignation, auditor removal, right of access to records and right to reasonable fees were maintained. Independence declaration

Section 307C requires an auditor to give the directors a written declaration to the effect

that, to the best of the auditor’s knowledge, there have been no contraventions of the

auditor independence requirements of the Corporations Act 2001 or of any Page 100

applicable code of professional conduct in relation to the audit, or that the only

contraventions have been those set out in the declaration. The directors’ report must

include a copy of the auditor’s independence declaration in accordance with section 298(1) (c). lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Conflicts of interest

It is a breach of the general auditor independence requirements under section 324CA for

the auditor to be aware of a conflict of interest situation in relation to the audit client and

not to take reasonable steps to ensure that the conflict of interest situation ceases to exist

as soon as possible. If, seven days after becoming aware of it, the conflict of interest

situation still exists, the auditor is required to notify ASIC. If the auditor is not aware of

the conflict of interest, but would have been aware if they had in place a quality control

system reasonably capable of making the auditor aware, the auditor will still be in

contravention of section 324CA.

Section 324CD indicates that a conflict of interest situation exists if:

the auditor or a professional member of the audit team is not capable of exercising

objective and impartial judgment in relation to the conduct of the audit a reasonable

person, with full knowledge of all relevant facts and circumstances, would conclude that

the auditor or a professional member of the audit team is not capable of exercising

impartial judgment in relation to the conduct of the audit.

When considering whether an auditor is capable of exercising objective and impartial

judgment, consideration needs to be given to past, current or possible relationships between:

the auditor, audit firm, current or former audit firm member, audit company or any

current or former audit company director