Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Page 35 CHAPTER 2

Audit regulation, structure of the profession and auditor’s liability

LEARNING OBJECTIVES (LO) 2.1

Identify the attributes of professional status and describe to what extent

they exist in public accounting.

2.2Describe the regulation of auditing and its subject matter.

2.3Explain the impacts of internationalisation on auditing.

2.4Outline the characteristics of the professional bodies and accounting

firms engaged in the auditing profession, and describe the internal structure of an audit firm. 2.5

Identify the elements of quality control within audit firms, and explain practice-monitoring programs.

2.6Explain the concepts of reasonable care and skill, and negligence.

2.7Explain the auditor’s legal liability to clients.

2.8Explain the auditor’s liability to third parties.

2.9Describe alternative methods used to limit the auditor’s liability. RELEVANT GUIDANCE ASA 101

Preamble to Australian Auditing Standards ASA 220/ISA 220

Quality Control for an Audit of a Financial Report and

Other Historical Financial Information ASA 501/ISA 501

Audit Evidence—Specific Considerations for

Inventory and Segment Information/Audit Evidence —

Specific Considerations for Selected Items ASQC 1/ISQC 1

Quality Control for Firms that Perform Audits and

Reviews of Financial Reports and Other Financial

Information, Other Assurance Engagements and Related Services Engagements lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 ASAE 3000/ISAE 3000

Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or Reviews of

Historical Financial Information

Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants APES 110/IFAC

Conformity with Auditing and Assurance Standards APES 210

Quality Control for Firms APES 320

Foreword to AUASB Pronouncements AUASB

Framework for Assurance AUASB/IAASB

Engagements/International Framework for Assurance Engagements

Preface to the International Standards on Quality IAASB

Control, Auditing, Review, Other Assurance and Related Services Page 36 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 CHAPTER OUTLINE

The auditor is a member of a time-honoured profession, and the status of the

profession and the responsibilities that accompany this status affect the audit and

assurance function and the structure of the profession. The auditor is subject to

regulations imposed by the profession and by society. The audit and assurance

function is carried out in a complex environment composed of interrelationships

between governmental and professional organisations and individual auditors and

audit firms. These regular and enduring relationships form the structure of the

profession. In addition, the audit environment includes the requirements of

legislation, particularly the Corporations Act 2001, discussed in Chapter 1 ; public

expectations of the audit and the existence of the expectation gap, also discussed in

Chapter 1 ; and the legal liability of an auditor and the impact of common law, discussed in this chapter.

This chapter explains the role of government and professional associations in the

auditing and assurance environment and the relationship between them. It recognises

the impact of globalisation on business and the auditing profession and discusses how

the profession has reacted to the need for

internationalisation. It outlines the characteristics of the types of audit firms that make

up the auditing profession and the services they provide. The internal structure of an

audit firm and the influence of that structure on an auditing practice are also covered.

There is also discussion of the quality control procedures that are essential to ensure

that auditors meet their responsibilities to clients and other users and carry out the

audit in accordance with legislation, the auditing standards and the ethical rules.

Finally, this chapter considers an auditor’s legal liability to clients and third parties. The

concept of reasonable care and skill is explained and the elements necessary for a

claim of negligence to be successful are outlined with reference to legal cases. The

concept of contributory negligence and methods used to limit the auditor’s liability are discussed.

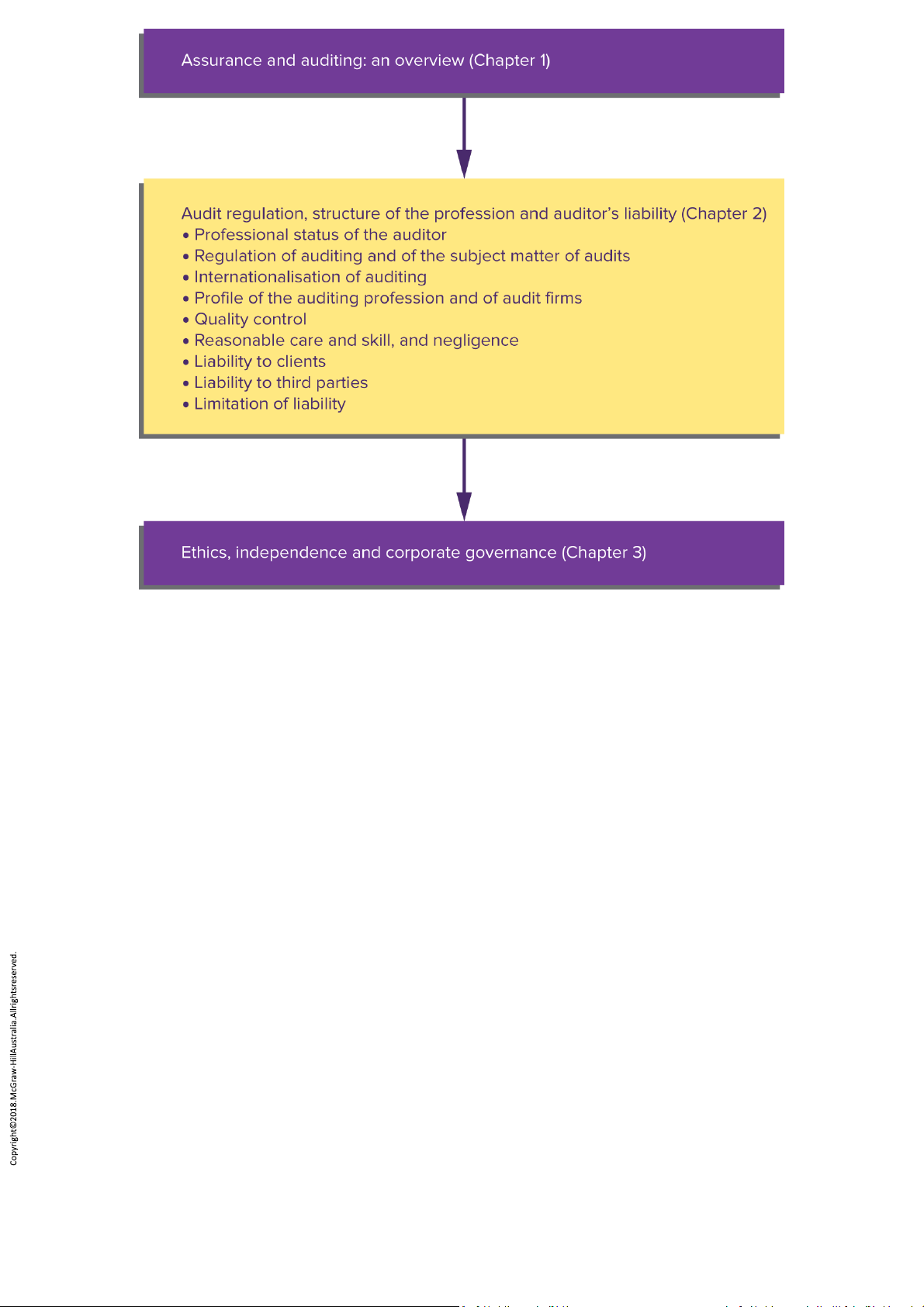

How this chapter fits into the overall auditing and assurance profession is illustrated in

Figure 2.1 , which is an expansion of part of the overall flowchart provided in Chapter 1 . lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

FIGURE 2.1 Flowchart of auditing and assurance profession lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Page 37

LO 2.1 Professional status of the auditor

The status of a profession can be determined by the extent to which the professional

group exhibits certain attributes which distinguishes it from those that are

nonprofessional. Greenwood (1957) indicates that all professions seem to possess five

elements: systematic theory; professional authority and expertise; community sanction;

regulative codes; and a culture. Systematic theory

One significant difference between a professional and a non-professional occupation is

the underlying body of theory that supports the work of the professional. Although

nonprofessional work may require procedural skill, that skill does not rest on a body of

systematic theory. The underlying theory of the auditing profession consists of auditing

theory and accounting theory. Knowledge of systematic theory can best be achieved

through formal education in an academic environment. Today, therefore, a tertiary

education is considered a prerequisite for people entering the auditing profession. They

are then required to complete the education program of one of the three accounting

bodies (Chartered Accountants Program, CPA Program or IPA Program) and also undertake

continuing professional development throughout their auditing career.

Professional authority and expertise

Expertise in the systematic theory of auditing and accounting is the basis for the auditor’s

work in these areas. Professionals have authority within the area of their expertise

because their clients lack the requisite theoretical knowledge. However, professionals

only have authority if society confers that authority upon them. Community sanction

Professionals normally attempt to formalise their authority by gaining community

approval of certain powers and privileges. First and foremost among the powers for which

professions strive is control over admissions to the profession. To be a registered company

auditor a person must, among other things, be a member of one of the accounting bodies lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

(discussed later in this chapter) or other prescribed bodies, each of which controls

admission to their own organisation.

Another privilege that professions strive for is relative immunity from community

judgment on technical matters. Although professions are responsible to the community

for their actions, it is generally accepted that a professional’s performance should be

judged by standards established by the profession itself. Prior to the CLERP 9 legislative

amendments, made as part of the Corporate Law Economic Reform Program, discussed in

Chapter 3 , the setting of auditing and assurance standards was undertaken by the

accounting bodies through the Australian Accounting Research Foundation (AARF). While

auditing standards are now set by the Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB),

which is an independent statutory body, the profession contributes heavily to the process,

with a majority of AUASB members being members of the profession, and members of

the profession also contributing to the consultation/development process for auditing

standards, as discussed later in this chapter.

Among the powers and privileges for which professions strive, privileged communication

stands out as perhaps the ultimate criterion of professionalism. Professional performance

is facilitated if the client feels free to volunteer information which otherwise might not be

divulged. Privileged information is a right granted by the community to protect the client

from legal encroachment on confidential communications with a professional. Although

the professions of medicine and law have generally been granted this privilege, legal

privilege between auditor and client does not exist. However, because an auditor will

have access to information that a client would not normally make available to external

parties, the ethical rules of the accounting bodies (discussed in Chapter 3 ) prohibit

auditors from disclosing such information to a third party without specific authority from

the client or unless there is a legal or professional duty to disclose, such as under section

311 of the Corporations Act 2001. Page 38 Regulative codes

The powers and privileges granted to a profession by the community effectively constitute

a monopoly. In Australia, registered company auditors have been granted a monopoly on

rendering external auditors’ opinions on the financial reports of companies. Since any

monopoly is subject to abuse, a profession must take steps to assure the community that lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

the profession will discipline its members. Professions therefore establish regulative codes.

Regulation of the auditing profession is directed at two areas: technical and ethical.

Auditing standards govern the technical work of the auditor while the ethical rules govern the auditor’s behaviour. A culture

Another distinguishing feature of a profession is a well-established culture that applies to

the professional group. Sociologists call this a subculture. A subculture contains specific

behavioural prescriptions and proscriptions. For example, auditors are expected to behave

in a way that is in accord with APES 110 Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants,

including exhibiting integrity, independence, objectivity, confidentiality and public

interest. New members of the profession must learn what is expected of them or they will

not be accepted as colleagues by their associates. QUICK REVIEW

1. Auditing is a profession.

2. The auditing profession is regulated largely by the auditing and assurance

standards and its own ethical rules.

3. Confidentiality is an important requirement for the auditing profession.

LO 2.2 Regulation of auditing and of the subject matter of audits Regulation of auditing

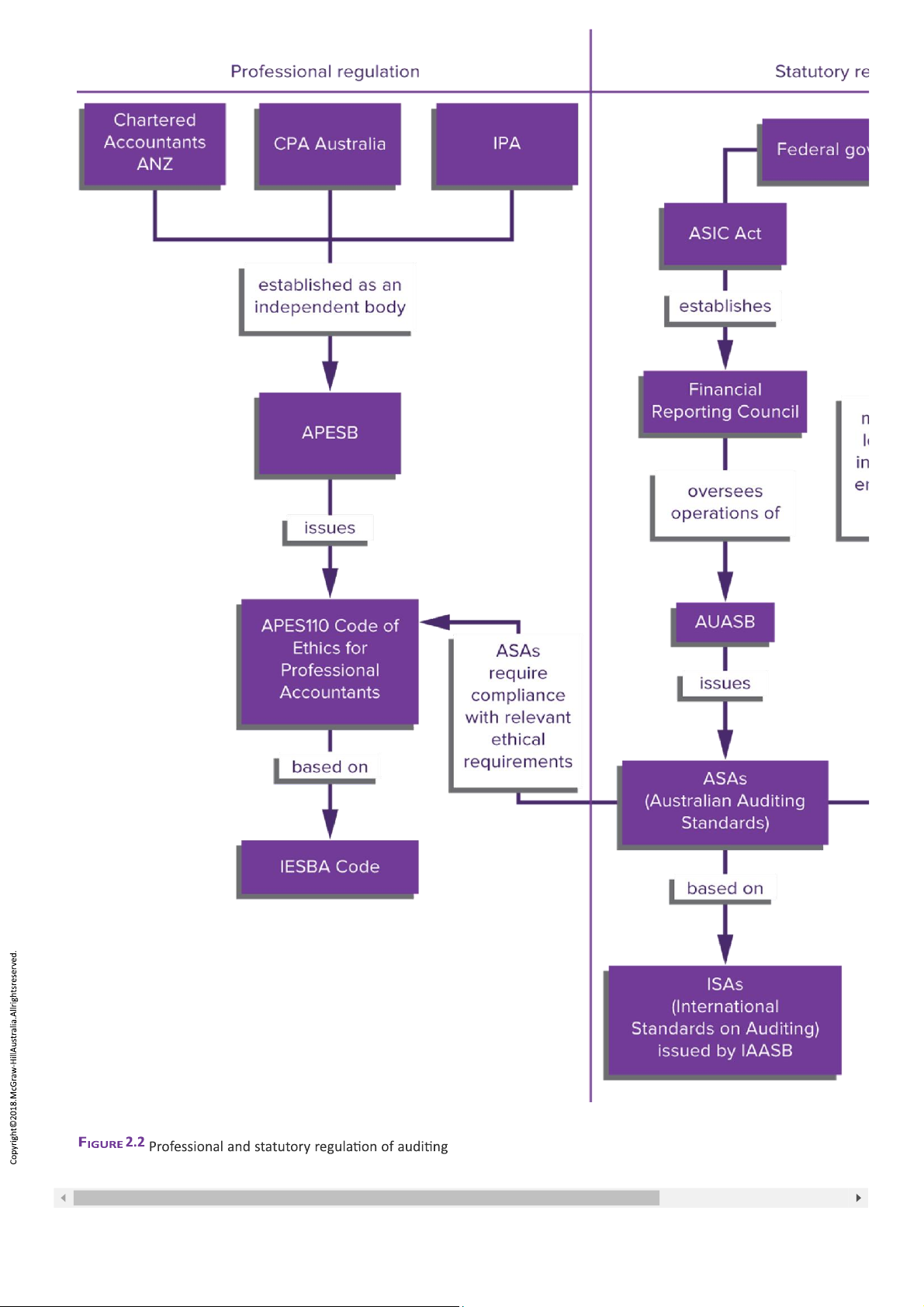

Our society is so complex that there is a whole set of organisations whose function is to

organise and supervise other organisations. The organisations of this type that are of

concern to the auditing profession include both government agencies and professional

associations that regulate auditing as indicated in Figure 2.2 . (In addition, there are

similar agencies that regulate the subject matter of audits, which we will discuss separately below.) lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 Financial Reporting Council

The Financial Reporting Council (FRC) is a statutory body established under section 225(1)

of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001. The FRC was

established during 1999 as a peak body with responsibility for the broad oversight of the

accounting standard-setting process for the private, public and not-for-profit sectors. As a

result of the CLERP 9 amendments, the FRC’s role has been significantly expanded to

include broad oversight of the auditing standard-setting process and monitoring of auditor independence.

Specific matters for which the FRC is responsible include:

overseeing the operations of the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) and the

Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB), including appointing their

members, other than the chairs, who are appointed by the Treasurer monitoring the

development of international accounting and auditing standards and accounting and

auditing standards that apply in major international financial centres furthering the

development of a single set of accounting and auditing standards Page 39 for worldwide

use with appropriate regard to international developments monitoring the operation of

Australian accounting and auditing standards to assess their continued relevance and

effectiveness in achieving their objectives monitoring auditors’ independence

monitoring the effectiveness of the consultative arrangements used by the AASB and AUASB

seeking contributions towards the costs of the Australian accounting and

auditing standard-setting process monitoring and periodically reviewing the level

of funding, and the funding arrangements, for the AASB and AUASB.

The legislation expressly limits the FRC’s ability to become involved in the technical

deliberations of the AASB and AUASB. As a result, the FRC does not have the power to

direct the AASB or AUASB in relation to the development, or making, of a particular

standard, or to veto a standard formulated or recommended by the AASB or AUASB. This

provision is designed to ensure the independence of the AASB and AUASB.

Auditing and Assurance Standards Board Page 40

As a result of the CLERP 9 amendments, the AUASB was reconstituted and established as

an independent statutory body on 1 July 2004. The AUASB is responsible for developing lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

and maintaining auditing and assurance standards and other publications, and consists of

11 members, including the chair. The members of the AUASB are appointed by the FRC

and the chair is appointed by the Treasurer. Membership currently includes auditing

practitioners from the private and public sectors and non-auditors from academia and

other stakeholder groups. The members are supported by the full-time technical staff of

the AUASB. Responsibility for final approval of auditing and assurance standards now lies

with the Parliament, as these are now disallowable legal instruments, following the CLERP

9 amendments. Auditors are required to follow these standards and therefore they are an

important influence on the way in which members of the profession perceive and

discharge their audit responsibilities.

The AUASB has developed a strategy document for 2017 to 2021 which sets out its vision,

mission and strategic objectives (see Auditing in the global news 2.1 ). For the first time

the AUASB’s strategy document has been aligned with that of the AASB and the strategy

documents of the two boards have been issued together, illustrating that the two boards

are working closely together to better achieve the desired outcomes. In order to achieve

their strategic objectives, the AASB and AUASB have both indicated that they will use

collaboration, communication, research and education as enablers. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

2.1 Auditing in the global news ... lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

AUASB strategy, 2017–2021 AUASB Vision

Contribute to stakeholder confidence in the Australian economy, including its capital

markets, and enhanced credibility in external reporting through independent auditing and assurance. AUASB Mission

Develop, issue and maintain in the public interest, high quality Australian auditing

and assurance standards and guidance that meet user needs and enhance audit and

assurance consistency and quality. Contribute to the development of a single set of

auditing and assurance standards and guidance for world-wide use.

AUASB Strategic Objectives

1. Develop, issue and maintain high quality Australian auditing and assurance

standards and guidance that meet the needs of external report users. Use IAASB

Standards—where they exist, modified as necessary—or develop Australian-specific standards and guidance.

2. With the AASB, play a leading role in reshaping the Australian external reporting

framework by working with regulators to develop objective criteria on: who

prepares external reports (including financial reports) the nature and extent of

assurance required on external reports. 3.

Actively influence international auditing and assurance standards and

guidance by demonstrating thought leadership and enhancing key international relationships.

4. Attain significant levels of key stakeholder engagement, through collaboration, partnership and outreach.

5. Influence initiatives to develop assurance standards and guidance that meet user

needs for external reporting beyond financial reporting.

6. Monitor and respond to emerging issues impacting the development of auditing

and assurance standards and guidance, including changing technologies.

7. Develop guidance and education initiatives, or promote development by others, to

enhance consistent application of auditing and assurance standards and guidance. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

Source: Australian Accounting Standards Board and Auditing and Assurance Standards Page 41 Board (2017)

AASB and AUASB Strategy, 2017-2021. http://www.auasb.gov.au/admin/file/co ntent102/c3/AASB-

AUASB_Strategy_2017-2021.pdf. Accessed 15 December 2017. (c) 2018 Auditing and Assurance Standards

Board (AUASB). The text, graphics and layout of this publication are protected by Australian copyright law and

the comparable law of other countries. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in

any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the AUASB except as permitted by law. For

reproduction or publication permission should be sought in writing from the Auditing and Assurance Standards

Board. Requests in the first instance should be addressed to the Technical Director, Auditing and Assurance

Standards Board, PO Box 204, Collins Street West, Melbourne, Victoria, 8007.

The AUASB has a longstanding policy of convergence and harmonisation with

International Standards on Auditing (ISAs). In 2003, the AUASB issued its current policy on

harmonisation and convergence of Australian Auditing Standards (ASAs) with ISAs, which

states that the AUASB endeavours to ensure that the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards:

are issued to cover the topics addressed in ISAs comply with those standards.

The AUASB has used ISAs as the basis for its corresponding ASAs. It is the policy of the

AUASB to aim to ensure that compliance with ASAs will also constitute compliance with

ISAs. Where it is necessary to cover specific Australian industry or regulatory

requirements not addressed in an ISA, the AUASB has indicated that it will include

additional paragraphs designated as ‘Aus’, with appropriate detailed explanation or

references by way of footnotes or appendices to the corresponding ASA. The AUASB has

indicated that in certain circumstances substantive amendments may be made to the

mandatory basic principles and essential procedures of an ISA to reflect additional

Australian professional auditing requirements or in order for it to conform to Australian

legislative and regulatory requirements.

Irrespective of the source of a standard, the document will have been through an

extensive process of development. This process is considered essential to ensure that all

interested parties are given sufficient opportunity to express their views and that the

standards, practices and guidelines developed are technically appropriate, relevant and logical.

Following full consideration of the views expressed on an exposure draft, a final auditing

standard is prepared and approved by the board. As a result of the CLERP 9 amendments,

it is now not until the document is formally approved by the Parliament that the extensive lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

process of development is complete (that period normally being one to three years) and

the document achieves the status of an auditing standard and therefore an authoritative

statement on the conduct of an audit.

The auditing standards are applicable to all audits, and for audits undertaken under the

Corporations Act 2001 the standards have legal authority. Failure to observe these

standards may expose a member to investigation and disciplinary action by the Australian

Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), as discussed below. For other audits and

assurance engagements there is a mandatory obligation, which is found in APES 210

Conformity with Auditing and Assurance Standards, issued by the Accounting Professional

and Ethical Standards Board (APESB), for members of the accounting bodies in Australia to

comply with the auditing and assurance standards.

Each auditing standard is required to state the objective to be achieved in relation to the

subject matter of the standard. The auditor will always be required to achieve the

objective stated in each standard, where the standard is relevant in the circumstances of

the audit. All auditing standards now contain the following sections (ASA 101/Preface to

the International Standards on Quality Control, Auditing, Review, Other Assurance and Related Services):

Introduction: the scope and effective date of the standard

Objective: the objective to be achieved by the auditor

Definitions: the terms that need to be defined within the standard

Requirements: the requirements to be complied with, together with explanatory material

necessary to make the section understandable by an experienced auditor

Application and other explanatory material: material, supplemented in some cases by

appendices, that provides further explanation and guidance supporting proper

application of the auditing standard.

In what are expected to be rare and exceptional circumstances, where the auditor is Page

42 unable to comply with a requirement contained in an auditing standard, the auditor is

required, if possible, to perform appropriate alternative audit procedures, and to

document in the working papers:

the circumstances surrounding their inability to comply

the reasons for their inability to comply lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

a justification of how alternative audit procedures achieve the objective(s) of the mandatory requirement.

Where the auditor is unable to perform appropriate alternative audit procedures, they are

required to consider the implications for the auditor’s report. (ASA 101; the Preface to the

International Standards on Quality Control, Auditing, Review, Other Assurance and

Related Services contains similar guidance at the international level.)

Accounting Professional and Ethical Standards Board

Until 2006, the accounting bodies maintained control of the setting of ethical standards,

which were promulgated through a joint Code of Professional Conduct (CPC).

In 2006, a body independent of the professional accounting bodies, the Accounting

Professional and Ethical Standards Board (APESB), was formed. The APESB consists of six

members, five of whom are drawn from across the three professional accounting bodies

and an independent chair. APESB standards covering quality control (APES 320), ethical

conduct (APES 110) and compliance with auditing and assurance standards (APES 210)

were issued in May and June 2006 to coincide with the auditing standards obtaining the

force of law with effect from 1 July 2006. Since then a number of additional APESB

standards have been issued, as will be discussed in Chapter 3 .

Standards set by the APESB apply to audits and assurance services carried out by

members of the professional accounting bodies. The fact that the profession has a body of

ethics and quality control procedures helps to boost its reputation. These measures will

be discussed in more detail later in this chapter (quality control) and Chapter 3 (ethics).

Australian Securities and Investments Commission

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) is an independent

Commonwealth government body established by the Australian Securities and

Investments Commission Act 2001. It operates under the direction of three full-time

commissioners, appointed by the Governor-General on the nomination of the Treasurer,

and reports to the Commonwealth Parliament and to the Treasurer. lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

ASIC began on 1 January 1991 as the Australian Securities Commission, to administer the

Corporations Law. It replaced the National Companies and Securities Commission (NCSC)

and the corporate affairs offices of the states and territories.

In July 1998, it received new consumer protection responsibilities and changed its name

to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. ASIC enforces company and

financial services laws to protect consumers, investors and creditors. It also regulates and

informs the public about Australian companies, financial markets, financial services

organisations and professionals who deal and advise in investments, superannuation,

insurance, deposit taking and credit.

On 15 July 2001, the Corporations Law was replaced by the Corporations Act 2001 and the

ASIC law was replaced by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001.

The new statutes are very similar to the laws that they replaced. The changes made

consist only of changes in terminology and some changes to reflect the new constitutional

underpinnings of the legislation, which is now truly Commonwealth legislation, as the

states have referred their powers to the Commonwealth in relation to registration and

regulation of companies. Section references and numbers have remained essentially unchanged.

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 requires ASIC to:

uphold the law uniformly, effectively and quickly

promote confident and informed participation by investors and consumers in the financial system

make information about companies and other bodies available to the public

improve the performance of the financial system and the entities within it.

ASIC has the power to investigate all perceived serious breaches of the Page 43

Corporations Act 2001, to take action to recover property or damages and to lodge criminal prosecutions.

Following the CLERP 9 amendments, ASIC’s responsibilities have been enhanced. It now

has the following responsibilities concerning oversight of the audit function: lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071 registration of auditors enforcing auditor independence

assessing whether auditors meet the registration requirements concerning practical

experience, education and competency standards post-registration supervision, through

an audit inspection program to ensure audit quality receiving auditors’ annual

statements concerning the nature and complexity of audit work undertaken and

compliance with any conditions of registration

referring matters with respect to the conduct of auditors to the Companies Auditors Disciplinary Board.

Companies Auditors Disciplinary Board

The Companies Auditors Disciplinary Board (CADB) is established under the Australian

Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001. ASIC may make applications to the

board to determine whether auditors have breached the Corporations Act 2001. The

board has the power to impose penalties if it determines that a registered auditor has

failed to carry out duties properly or is not a fit and proper person to be registered.

Penalties may include suspension or cancellation of the auditor’s registration, the

imposition of restrictions on conduct or an admonition.

Matters that may be referred to the CADB include:

failure on the part of an auditor to lodge an annual statement

failure to comply with the conditions of registration

failure to maintain sufficient practical experience, as indicated by a failure to perform

any audit work during a continuous period of five years

failure to perform adequately and properly the duties of an auditor

ceasing to be a fit and proper person to remain registered.

As will be discussed later in this chapter, partners involved in the audits of high-profile

corporate collapses such as Westpoint and Centro had their registered company auditor registrations suspended.

Section 324 of the Corporations Act 2001 provides that a person cannot be appointed as

an auditor of a company unless they are a registered company auditor. Further, section

1280 requires that a person applying for registration must: lOMoAR cPSD| 47206071

be ordinarily resident in Australia

be a member of an approved body

be a graduate of a prescribed university or other prescribed institution in Australia

and have passed a course of study in accountancy and commercial law acceptable to

ASIC have sufficient auditing experience be a fit and proper person.

ASIC Regulatory Guide 180 Auditor Registration provides more detail of what is required

to meet these requirements. For example, to have sufficient auditing experience, an

auditor must have completed at least 3000 hours of work in auditing during the five years

immediately prior to the date of their application, including at least 750 hours spent

supervising audits of companies.

ASIC may approve auditing competency standards on application of any professional body

or accounting firm under section 1280A(1) of the Corporations Act 2001. In November

2004, ASIC approved its first auditing competency standard prepared by CPA Australia and

The Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia (now Chartered Accountants ANZ). The

competency standard enables auditors to fill out a logbook to demonstrate onthe-job

experience in their audit competency skills and have this certified by a current registered

company auditor. This replaces the previous requirement to meet a specified number of hours.

To meet the educational requirements, auditors will be required to have completed Page 44

a specialist course in auditing, which will be prescribed under the Corporations

Regulations and administered by the professional accounting bodies.

Structure of assurance standards and pronouncements

The structure of the assurance standards and pronouncements issued by the AUASB is

outlined in Figure 2.3 . This is similar to the structure of the standards and

pronouncements issued by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board

(IAASB), which is responsible for setting auditing and assurance standards at international level.