Preview text:

CHAPTER 1: THINK LIKE AN ECONOMIST.

1, Một vài khái niệm cơ bản

- Hoạt động kinh tế: là một hoạt động sử dụng nguồn lực của xã hội nhằm tạo ra các sản phẩm (hữu hình

hay vô hình) thỏa mãn nhu cầu khác nhau của con người.

(1) Hoạt động sản xuất. Đó là việc tổ chức, sử dụng các nguồn lực nhằm tạo ra những vật phẩm

hay dịch vụ thỏa mãn nhu cầu của con người.

+ Sản phẩm đầu ra: vật phẩm và dịch vụ, được gọi là hàng hoá

+ Sản phẩm đầu vào: các nguồn lực = yếu tố sản xuất

Mục đích: tiêu dùng (2) => hoạt động kinh tế quan trọng

+ Đối tượng của hành vi tiêu dùng: hàng hoá

Hoạt động sản xuất có hiệu quả nhờ (3) trao đổi

(4) Phân phối:

+ Phụ thuộc vào yếu tố đầu vào

+ Gắn chặt với cách thức sản xuất

- Lí do: người ta luôn phải đương đầu với sự lựa chọn khi ra các quyết định.

- Lựa chọn – đó chính là thực chất của các quyết định kinh tế.

- Economics (Định nghĩa Kinh tế học) is the study of how people make choices under conditions of

scarcity and of the results of those choices for society. (Kinh tế học là môn khoa học xã hội)

- The Scarcity Principle (also called the No-Free-Lunch Principle): Although we have boundless needs

and wants, the resources available to us are limited. So having more of one good thing usually means having less of another.

- The Cost-Benefit Principle: An individual (or a firm or a society) should take an action if, and only if, the

extra benefits from taking the action are at least as great as the extra costs.

- Economic surplus = the benefit of taking an action – its cost

- Opportunity cost the value of what must be forgone to undertake an activity.

+ All costs—both implicit and explicit—are opportunity costs.

+ Note that the opportunity cost is not the combined value of all possible activities you could have

pursued, but only the value of your best alternative.

2, Three important decision pitfalls

Pitfall 1: measuring costs and benefits as proportions rather than absolute dollar amounts

Example: What would you do, walk downtown to save $10 on a $2020 laptop computer or save

$10 on a $25 wireless keyboard?

Answer: If you are rational, you will make the same decision in both cases. This is because “The

benefit of the trip downtown is not the proportion you save on the original price. Rather , it is the

absolute dollar amount you save. In these two cases, the cost of the trip is the same, both at $10 => same decision

Pitfall 2: ignoring implicit costs

Example 1: If buying a wireless keyboard downtown means not watching another hour of your

favorite show on Netflix, then the value to you of watching the show is an implicit cost of the trip.

Solution: Instead of asking “Should I walk downtown?”

Ask “Should I walk downtown or watch another hour of my favourite show?”

Example 2: The use of frequent-flyer coupon to fly to Cancun.

There are two ways to use this coupon:

1. Use to go to Cancun with a group of classmates at University

2. Use for a trip to Boston to attend brother’s wedding.

Without the coupon, the cost of making the trip to attend brother’s wedding at Boston is

$400. Therefore, although using the coupon for the trip to Cancun making the trip seem to be

free, you actually have to pay $400 for the trip to Boston. Therefore $400 is the implicit cost

(contributing to the opportunity cost) of going to Cancun.

Pitfall 3: failing to think at the margin

People are often influenced by sunk costs—costs that are beyond recovery at the moment a decision is made.

Definition: Sunk cost a cost that is beyond recovery at the moment a decision must be made.

Those costs that cannot be avoided even if the action isn’t taken.

Example: In a restaurant, normally, people would have to pay $10 at the door for a buffet.

However, one day, the owner tell that 20 random guests won’t have to pay anything. The remaining

guests will have to pay the usual price. Would they eat the same amount of food?

Answer: If all the guests are rational, the answer would be YES. In this case, $10 at the door is

sunk cost, those who paid it have no way to recover it. Therefore, the extra cost of having more helping

is exactly zero, then, the extra benefit of having more helping is exactly the same. With the same cost

and benefit, their decision making should be the same.

3, Marginal Costs and Marginal Benefits

We use Marginal Costs and Marginal Benefits to answer the question: “Should I increase the

level at which I am currently pursuing the activity?”

The Cost-Benefit Principle tells us that the level of an activity should be increased if, and only if,

its marginal benefit exceeds its marginal cost.

Marginal cost: the increase in total cost that results from carrying out one additional unit of an activity.

Marginal benefit: the increase in total benefit that results from carrying out one additional unit of an activity.

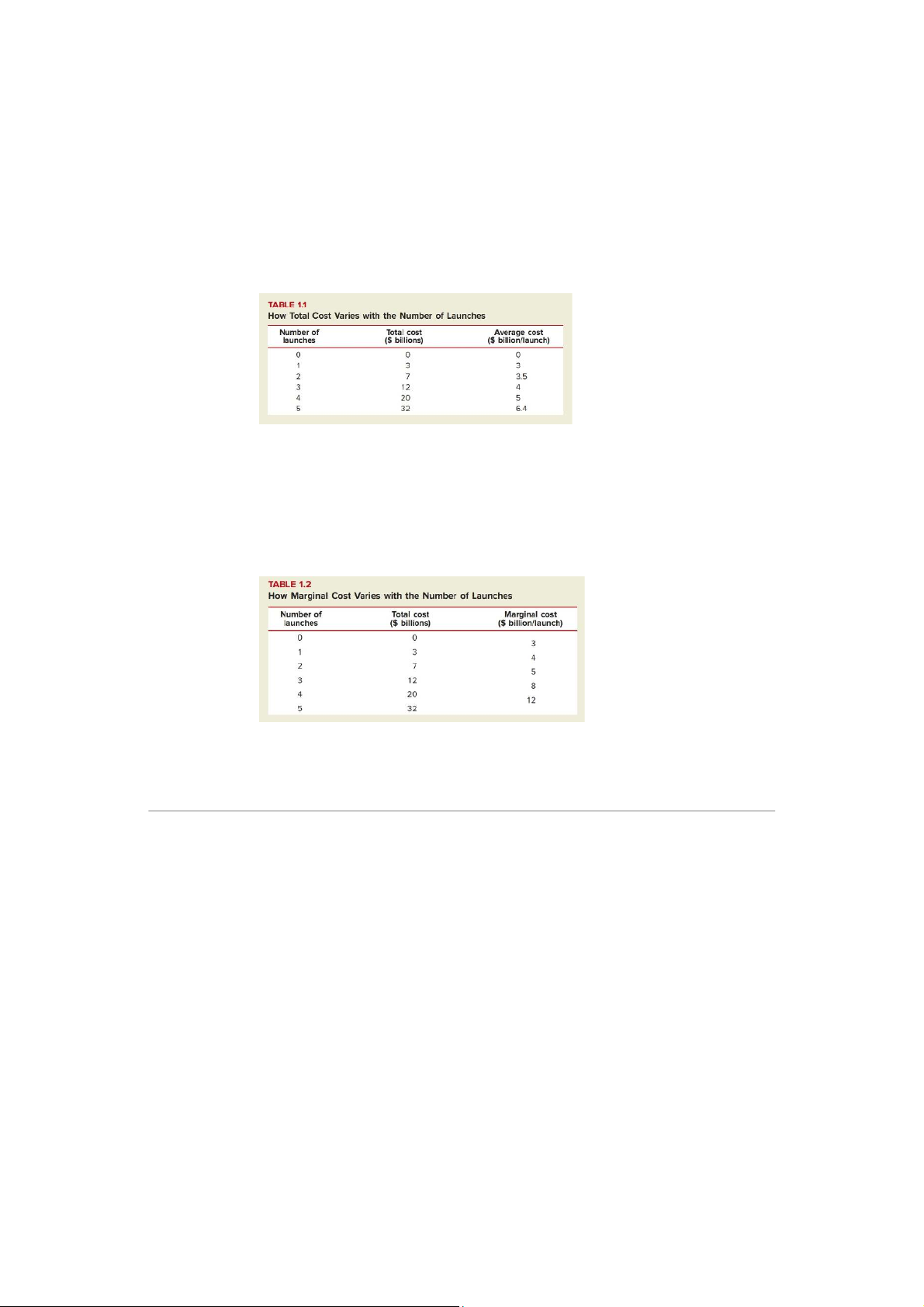

Example 1: A rocket launch program gains benefit of $24 billion a year (an average of $6 billion

per launch), but costs $20 billion a year (an average of $5 billion per launch). Should the compary expand its program?

Answer: In order to answer the question, we must compare the marginal cost of a launch to its.

However, there are only information for average cost and average benefit of the program, which are not

useful for making the decision.

For the sake of discussion, we suppose that the benefit of an additional launch is the same as

the average benefit, which is $6 billion. If we have the table below:

We note that adding the fifth launch, the cost raise from $20 billion to $32 billion, making the

marginal cost for the fifth launch is $12 billion. So if the benefit of the adding fifth launch is still $6

billion, the company absolutely should not expand its program.

Example 2: How many launches should the company make, if the benefit of each launch is $6

billion, and the cost depends on the table shown in Example 1?

The company should continue to make launches as long as the marginal cost of the program

doesn’t exceed its marginal benefit, which is $6 billion. According to the definition of Marginal Cost, we

can calculate the Marginal Cost of each launch as below.

In comparison of the marginal costs and benefits per launch, we can see that the three first

launches satisfy the cost-benefit test. However, the fourth and fifth launches does not. Therefore, the

company should make three launches.

4, The normative economics versus the positive ecnonomics

(Kinh tế học chuẩn tắc và Kinh tế học thực chứng)

a, The normative economics (Kinh tế học chuẩn tắc)

The Cost-Benefit Principle is an example of a normative economics.

Normative economic principle: one that says how people should behave

Phân tích chuẩn tắc: đưa ra những đánh giá và khuyến nghị dựa trên cơ sở các giá trị cá nhân của người phân tích.

+ Câu hỏi đặt ra là: cần phải làm gì hay cần phải làm như thế nào trước một sự kiện kinh tế?

+ Dựa trên các đánh giá của người phân tích, xem sự kiện là tốt hay xấu, đáng mong muốn hay không đáng mong muốn.

+ Các giá trị cá nhân sẽ ảnh hưởng đến đánh giá của mỗi người về sự vật. Do đó, giá trị cá

nhân khác nhau sẽ dẫn đến những nhận định khác nhau.

b, The positive (descriptive) economics (Kinh tế học thực chứng)

Positive (or descriptive) economic principle: one that predicts how people will behave.

Phân tích thực chứng: lý giải khách quan về các vấn đề hay sự kiện kinh tế.

+ Động cơ: cắt nghĩa, lý giải và dự đoán về các quá trình hay sự kiện kinh tế

+ Câu hỏi đặt ra là: Vì sao lại xảy ra? Có tác động như thế nào?

+ Kết luận chỉ được thừa nhận là đúng đắn nếu nó được kiểm nghiệm và xác nhận bởi chính các sự kiện thực tế.

=> Hạn chế chủ quan hoặc lí do khác (số liệu, chứng cứ thực tế) dẫn đến kết luận sai lầm.

This economics has lead to the Incentive Principle:

The Incentive Principle: A person (or a firm or a society) is more likely to take an action if its

benefit rises, and less likely to take it if its cost rises. In short, incentives matter

c, Ảnh hưởng qua lại của 2 cách tiếp cận Thực chứng và Chuẩn tắc

Kết luận thực chứng có thể ảnh hưởng đến nhận định chuẩn tắc. Bởi khi hiểu thêm về cách vận

hành khách quan (qua kinh tế học thực chứng) ta sẽ thay đổi cách nhìn nhận chuẩn tắc.

Song dù thế nào thì kết luận chuẩn tắc vẫn phụ thuộc nhiều vào chuẩn mực giá trị của mỗi người

=> Sự bất đồng trong quan điểm chuẩn tắc thường nhiều hơn trong quan điểm thực chứng.

5, Economics: Micro and Macro

a, Microeconomics:

The study of individual choice under scarcity and its implications for the behavior of prices and

quantities in individual markets.

Thực hiện trong khuôn khổ của một thị trường cụ thể tạm thời bỏ qua tác động từ thị trường khác.

+ Các đại lượng kinh tế chung = các biến số đã xác định.

+ Xem xét các cá nhân lựa chọn các quyết định như thế nào.

+ Tương tác giữa các cá nhân

+ Quan tâm đến biến động giá cả cụ thể, lượng hàng hoá cụ thể.

b, Macroeconomics:

The study of the performance of national economies and the policies that governments use to

try to improve that performance.

Xem nền kinh tế như một thể thống nhất.

+ Quan tâm đến đại lượng hay biến số tổng hợp của cả nền kinh tế.

+ Chú tâm đến sự giao động của mức giá chung, tổng sản lượng.

+ Thể hiện sự thay đổi trong mức giá chung bằng tỉ lệ lạm phát

+ Từ đó khảo cứu hậu quả và khả năng phản ứng từ chính sách nhà nước

6, Appendix: Working with Equations, Graphs, and Tables

a, From verbal description to an equation

Example: An electric scooter company charges $1 to unlock a scooter plus 20 cents per minute.

Write an equation that describes your bill for riding this scooter. Answer:

Step 1: Define dependent variables and independent variables.

+ Dependent variable is the dollars amount of your scooter bill (B)

+ Independent variable is number of minutes you ride the scooter (T) Step 2: Write the equation: B = 1 + 0.20T

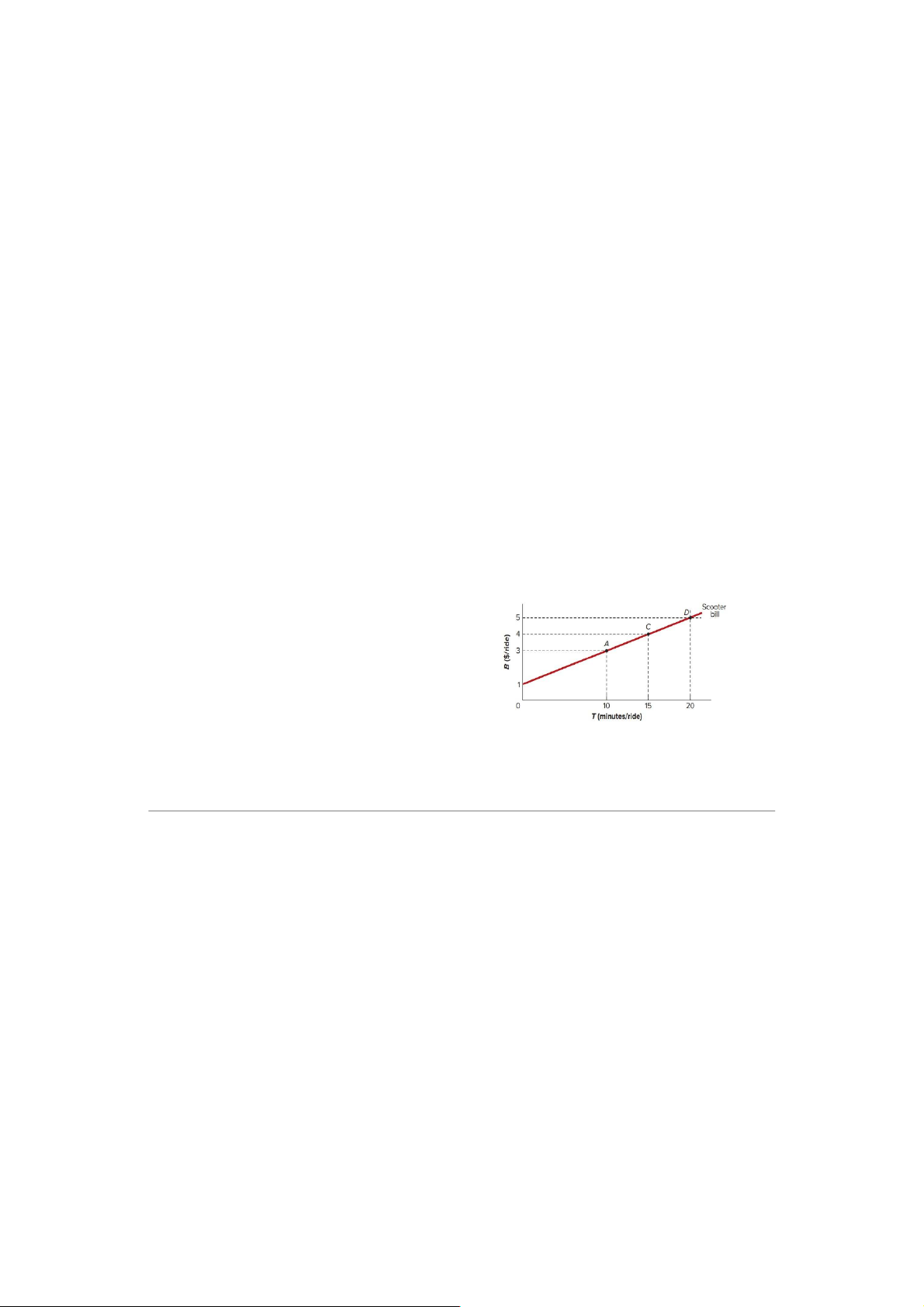

b, From equation to graph

Example: Construct a graph that portrays the scooter billing plan described in Example 1 Answer:

Step 1: Draw and lable axes

+ Horizontal is independent variable (T)

+ Vertical is dependent variable (B) Step 2: Graph + Plot the intercept (0,1)

+ Plot one other point. It could be A(10,3); B(15,4); C(20,5) + Connect the points.

c, From graph to equation

Example: Figure 1A.2 shows the graph of the billing plan for an electric scooter company. What

is the equation for this graph? How much is the fee to unlock a scooter under this plan? How much is

the charge per minute? Answer:

Step 1: Identify the variables:

+ Independent variable = the horizontal T

+ Dependent variable = the vertical B

Step 2: Identify parameters (constant) + The vertical intercept: 2 3.5−3 + The slope: =0.1 15−10 Step 3: Write the equation:

B = 2 + 0.1T

d, Changes in intercept vertical intercept and slope Vertical intercept Slope The graph Increase Unchanged Is shifted up Decrease Unchanged Is shifted down Change Unchanged Increase Steeper Unchanged Decrease Flatter

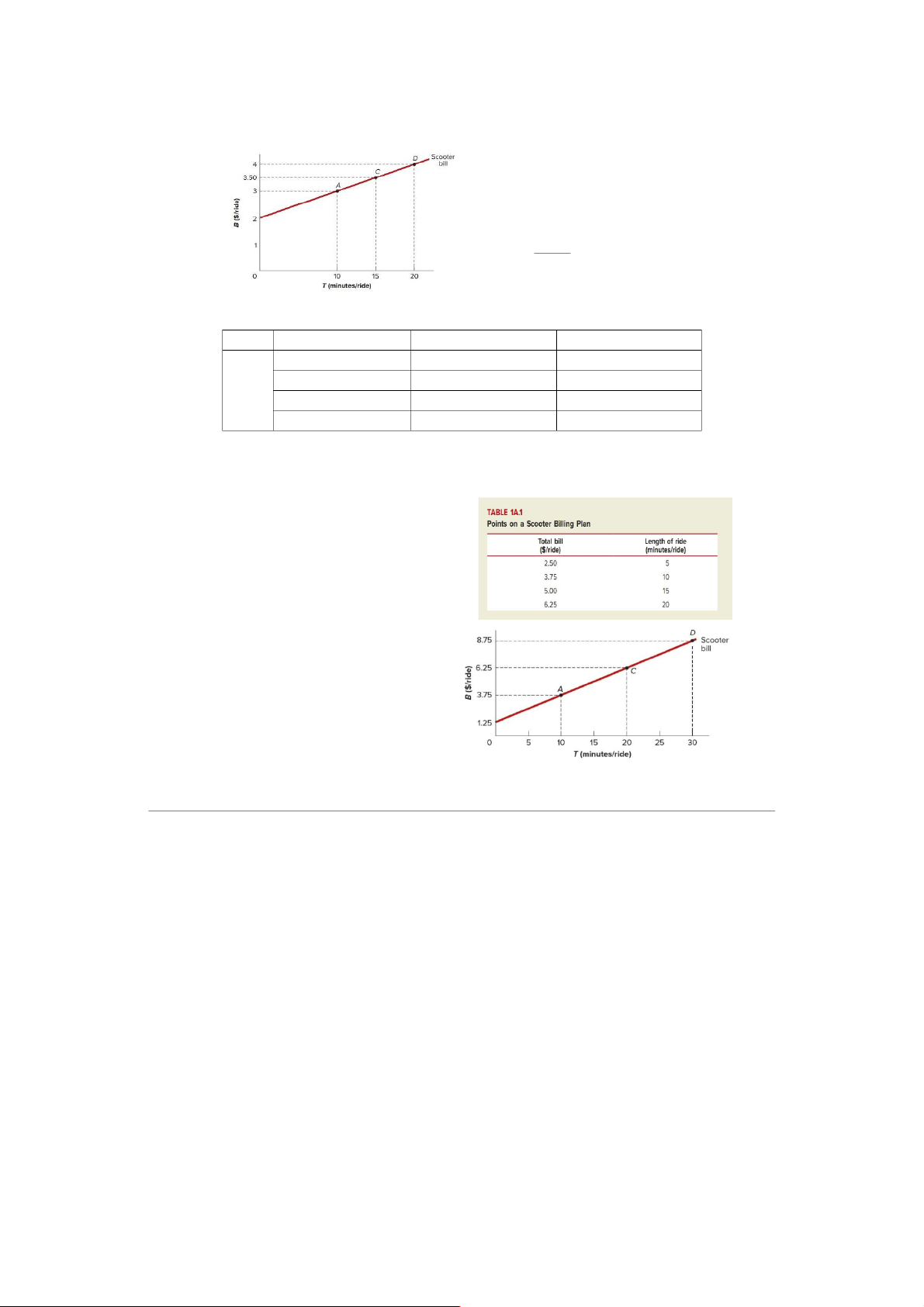

e, From a table to a graph

Example: Table 1A.1 shows four points from a scooter billing equation. If all points on this billing

equation lie on a straight line, find the vertical

intercept of the equation and graph it. Answer: Step 1: Identify variables

+ Independent: Length of ride (T) + Dependent: Total bill (B) Step 2: Draw axes Step 3: Plot points Step 4: Connect points

f, From table to equation

Example: Table 1A.1 shows four points from a

scooter billing equation. Form a equation

showing the relationship between the total

bill and the length of ride Answer: + Step 1: Identify

* independent variable: length of ride (T)

* dependent variable: total bill (B) 3.75−2.5

+ Step 2: Calculate the slope = =0.25 10−5

+ Step 3: Solve for intercept (f), using any point. We have: B = f + 0.25T

As the line passes (5,2.5), we have: 2.5 = f + 0.25 x 5 f = 2.5 – 0.25 x 5 f = 1.25

Therefore, the equation is: B = 1.25 + 0.25T

g, Solving simultaneous equations

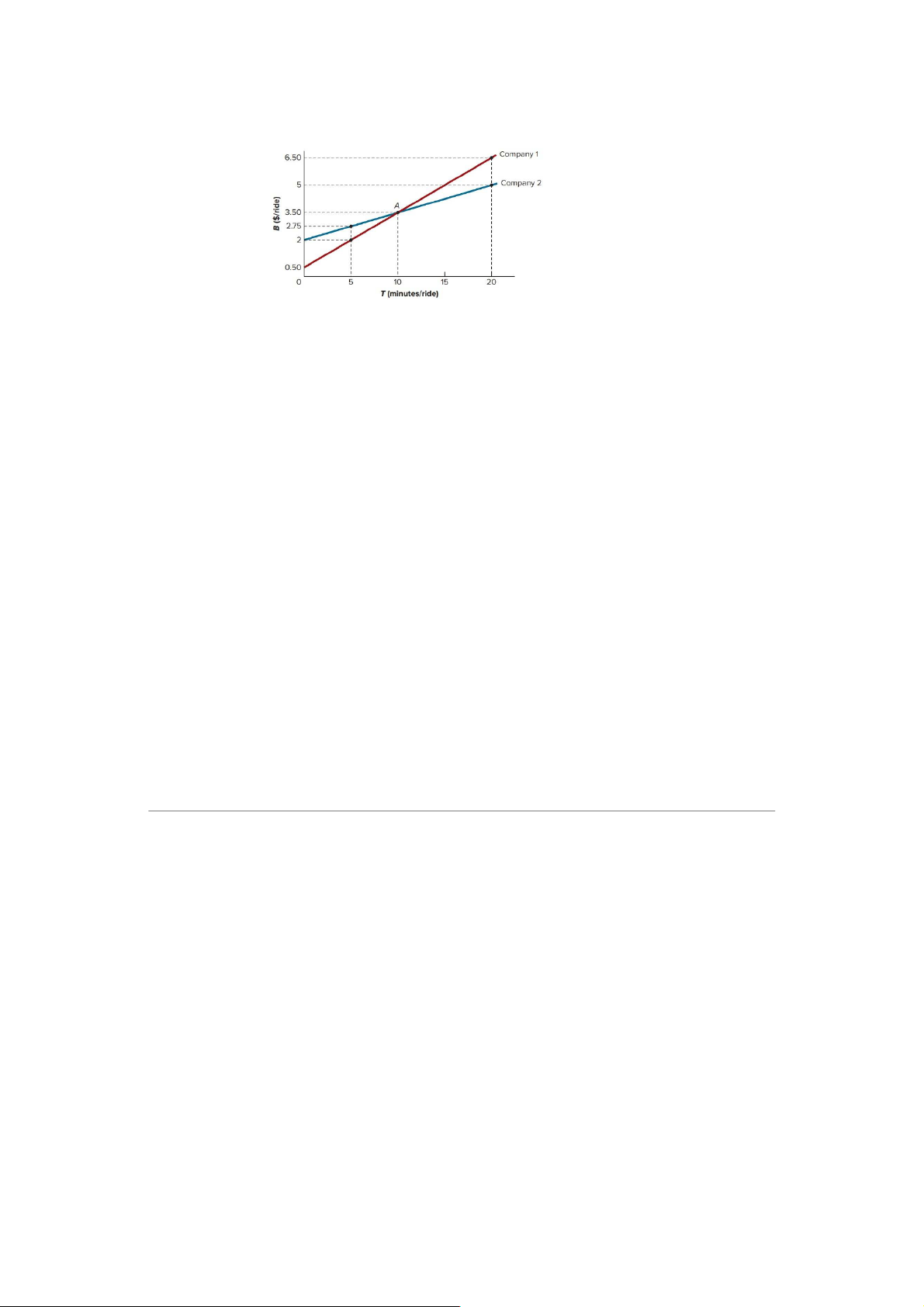

Example 1: Suppose you are trying to choose between two electric scooter companies. If you

choose Company 1, your bill will be computed according to the equation B = 0.20 + 0.40T (Company 1),

where B is again your bill in dollars and T is the length of your ride in minutes. If you choose

Company 2, your bill will be computed according to the equation B = 5 + 0.10T (Company 2).

Use the algebraic approach described in the preceding example to find the break-even ride length for these plans. Solution: We have:

Subtract the Company 1 equation from the Company 1 equation, we get:

Solving the last equation, we get T = 10

Plug T = 10 in any equation, we get B = 3.50

So (10,3.50) is the break-even point, where two companies break even.

The graph of the two equations: A is the bread even point. We can see that: + Company 1 has lower