Preview text:

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 751 The British Psychological

British Journal of Psychology (2010), 101, 751–776 Society

q 2010 The British Psychological Society www.bpsjournals.co.uk

‘I want it and I want it now’: Using a temporal

discounting paradigm to examine predictors of consumer impulsivity Helga Dittmar* and Rod Bond

University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

This paper proposes a new model of consumer impulsivity, using type of good, a

person’s endorsement of materialistic values, and identity deficits as predictors.

Traditional decision making and psychological accounts see impulsive behaviour as a

general overweighing of short-term gratification (I want that dress now) relative to

longer-term concerns, irrespective of consumer good. Our proposal is that consumers’

impulsivity (a) differs according to type of good and (b) is linked systematically to a

combination of materialistic values and high identity deficits. Beginning with Study 1,

three experiments, using a temporal discounting paradigm, show consistently that

discount rates are higher for goods that are seen as highly expressive of identity (e.g.,

clothes) than goods not expressive of identity (e.g., basic body care products). For

materialistic consumers, identity deficits predict discount rates for identity-expressive

goods (Study 2), and discount rates change for materialistic individuals when their

identity deficits are made salient (Study 3). These findings support a conceptualization

of consumer impulsivity as identity-seeking behaviour.

Impulsivity can be described as ‘acting without thinking’, where people are more

motivated by immediate reward, rather than by long-term consequences of their

behaviour. This characteristic of everyday decision making also applies to wanting

particular consumer goods now, rather than planning consumption over time to

maximize long-term satisfaction. Consumers often experience conflict between desiring

particular goods right now, on the spur of the moment, and wanting to spend their

money sensibly on objects from which they can be sure to derive benefits over time.

When the short-term desire wins out, the consumer engages in impulse buying. In a

qualitative study, consumers defined impulse buying as ‘Just buying it, quickly, without

going away and thinking about it, buying it straight away’ or ‘Something I see and don’t

plan and I think “I’d like that”’ (Dittmar & Drury, 2000, pp. 123–124). In this paper,

we define consumer impulsivity as decisions about material goods that are characterized

by a strong, immediate desire for the good in question, lack of deliberation or planning,

* Correspondence should be addressed to Dr Helga Dittmar, School of Psychology, Pevensey 1, University of Sussex,

Brighton BN1 9QH, UK (e-mail: h.e.dittmar@sussex.ac.uk). DOI:10.1348/000712609X484658

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 752 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond

and disregard for financial constraints (Baumeister, 2002; Dittmar, 2001; Verplanken &

Herabadi, 2001). We thus use the traditional definition of impulsivity that emphasizes

lack of forethought and deliberation (Ainslie, 1975; Martin & Potts, 2009), rather

than referring to impulsivity in terms of impatience (Frederick, Loewenstein, & O’Donoghue, 2002).

Impulse buying is extremely common, with 90% of people making such purchases at

least occasionally (Hausmann, 2000), yet people often wish afterwards they had not

done so. In studies of impulse buyers, 80% were found to refer to some negative

consequences from their purchases (Rook, 1987), and 55% explicitly reported regret at

least once in a purchase diary (Dittmar, 2001). The near ubiquity combined with the

potential negative impact of this behaviour highlights the need for a better

understanding of factors that impact consumer impulsivity.

Individuals are not, however, impulsive all the time or with respect to all the

decisions they make, but this is something not well-explained by traditional

perspectives in decision making and microeconomics. We have no systematic

explanation of the fact that, typically, impulse purchases tend to be made for some

types of consumer goods, such as fashionable clothes, rather than others, such as basic

body care products (e.g., Dittmar, 2001).

We propose to examine three predictors of consumers’ impulsivity, all linked to

identity, defined as the subjective concept (or representation) that a person holds of

her- or himself (Vignoles, Regalia, Manzi, Golledge, & Scabini, 2006). The first

predictor is type of consumer good. People are typically more psychologically invested

in material goods that offer a high potential for the expression and communication

of identity than goods that are purely or mainly functional (Csikszentmihalyi &

Rochberg-Halton, 1981; Dittmar, 1992, 2008, in press; Kamptner, 1991). We therefore

propose that goods high in identity-expressive potential are discounted more steeply.

The next two predictors are linked. One of these predictors, materialistic values, can

be defined as a ‘set of centrally held beliefs about the importance of possessions in

one’s life’ (Richins & Dawson, 1992, p. 308). Those who endorse materialistic values

believe that acquiring new material goods is vital, particularly goods that are

expressive of social status, fame, and image (Dittmar, 2008; Kasser & Kanner, 2004).

Implicit in this type of materialism is the assumption that material goods are a good

way of attaining a better, more positive identity – more status, more fame, and more

image – which should make the buying of identity-expressive goods particularly

important to those who, in addition to endorsing materialistic values, also have high

identity deficits. Identity deficits, the other predictor, are defined as the salience of

perceived gaps between a person’s actual self (how they are) and their ideal self

(how they would ideally like to be).

We use an adaptation of the matching technique in a temporal discounting paradigm

(e.g., Benzion, Rapoport, & Yagil, 1989), because it provides a useful quantitative

measure of the extent to which an immediate reward is preferred to a larger, but delayed

reward. This paper reports three experimental studies which test the proposed new

consumer impulsivity model. In line with recent challenges to the discounted utility

model (Frederick et al., 2002), the first experiment focuses on systematic differences in

discounting as a function of type of consumer good. The second experiment examines

individuals’ materialistic value endorsement and identity deficits as additional predictors

of discount rates, and the third demonstrates that an experimental manipulation of

identity deficits in materialistic individuals affects discount rates for a good with high identity-expressive potential.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 753

‘I want it and I want it now’: Previous theoretical frameworks

Consumer impulsivity is characterized by an immediate, strong desire for a particular

good, by a lack of deliberation and careful planning, and often disregard for financial

constraints and consequences (Baumeister, 2002; Dittmar & Drury, 2000). There is a

battle between self-control on one hand, and desire on the other: ‘The budget is tight,

the price is too high, the item is not desperately needed, and so the shopper should not

buy it. Ranged against these sensible concerns is a murky alliance of wants, impulses,

and emotions, all clamoring for the gratification of the purchase’ (Baumeister, 2002,

p. 670). Our definition of consumer impulsivity is consistent with traditional

approaches to impulsivity (Ainslie, 1975; Martin & Potts, 2009).

Both anecdotal and research evidence suggests that consumer impulsivity is strong

with respect to certain types of goods, such as fashionable clothes and accessories,

but not with respect to others, such as basic body care products or tools (Dittmar &

Beattie, 1998; Dittmar, Beattie, & Friese, 1995, 1996), yet traditional accounts in

microeconomics and psychology1 have tended to see consumer impulsivity as a general

overweighing of short-term gratification relative to longer-term concerns, irrespective of consumer good.

Consumer impulsivity is a problem for traditional microeconomic decision theory

because it implies time-inconsistent preferences that switch from ‘I want it now’ to

later regret, violating the central assumption of the discounted utility model that

individuals have a consistent and unitary rate of time preference according to which

they discount the value of all delayed events. One influential variation conceptualizes

intertemporal choice as the outcome of a conflict between different selves: a ‘myopic’

doer focused on immediate gratification and a ‘farsighted’ planner concerned with long-

term benefits. Impulse buyers are assumed to discount the future at too rapid a rate,

where the benefits of the desired object at the point of imminent purchase outweigh

the (future) problem of paying the bill (e.g., Strotz, 1956; Winston, 1980). This does not

explain, however, why discounting should be disproportionately high, or why and

when people shift between short- and long-term preferences.

Ainslie (e.g., Ainslie, 1975, 1992, 2005) has challenged the traditional model. He

argues that delaying rewards from the moment of choice causes them to lose

effectiveness, so that preferences between a small-early and larger-late reward switch at

some point. Hence, discount rates are delay-dependent and follow a hyperbolic

function. Although he does not explicitly refer to differential discount rates for different

types of consumer goods, his hyperbolic discounting model leaves open that possibility.

Recent work, similarly, has challenged the assumption of a ‘unitary discount rate that

applies to all acts of consumption’ (Frederick et al., 2002, p. 394), and a series of

experiments consistently shows that consumables, such as food or drinks, are

discounted temporally more steeply than money (Estle, Green, Myerson, & Holt, 2007;

Odum, Baumann, & Rimington, 2006; Odum & Rainaud, 2003). However, we still know

little about psychological factors that impact temporal discounting of consumer goods

(i.e., variations in discounting that are likely to reflect psychological motives; Frederick

et al., 2002; Green & Myerson, 2004; Loewenstein, Read, & Baumeister, 2003).

1 Consumer behaviour and marketing work on impulse buying has been descriptive and a theoretical, identifying factors which

increase unplanned purchasing, such as exposure to in-store stimuli (e.g., Abratt & Goodey, 1990), or developing lists of foods

and drinks most likely to be bought impulsively (e.g., Bel enger, Robertson, & Hirschman, 1978). This does not explain

underlying motives, nor predict beyond the particular goods studied, thus not offering predictions regarding temporal discounting.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 754 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond

Hoch and Loewenstein (1991) offer a reference point model where consumers imagine

themselves as owning the good before they actually purchase it, and hence experience

foregoing the purchase as a loss and therefore an additional cost. The probability of such

a ‘reference shift’ is affected by several factors, such as people’s evaluations of goods,

and hence impact impulsivity. In later work, Loewenstein (1996, 2000) focuses on

‘visceral’ influences that produce short-term increases in the attractiveness of certain

goods. Others have suggested that goods which are an investment, or which

complement an investment, may be discounted more steeply (Borghans, Duckworth,

Heckman, & ter Weel, 2008; Borghans & Goldsteyn, 2006). For example, if owning a

particular good helps people to study towards an important qualification, then that good

complements the investment in study, and will therefore have higher utility. However,

its utility in the future may not be clear to the individual since they cannot assess their

needs at that future date – a ‘lack of imagination’. Therefore, a good may not have a fixed

utility, but its utility may vary across time depending on an assessment of how it meets individual needs.

In our research, we focus on identity-related factors as a framework for

understanding characteristics of consumer goods and individual consumers that affect

temporal discounting. Identity, an individual’s subjective representation of her- or

himself (Vignoles et al., 2006), is multifaceted and, in addition to individual, relational,

and group levels of self-representation (Sedikides & Brewer, 2001), also includes

material goods as parts of individuals’ extended identity (Dittmar, 1992, in press). This

can be applied to within-individual variations, whereby individuals can be impulsive at

certain times, but not others, depending on whether goods are linked to identity or not,

and to between-individual variations, whereby some people are more impulsive than

others (i.e., those with stronger identity-related motives for material goods).

Traditionally, individual differences in impulsivity have been explained in terms

of impulse control and personality traits. The ability to delay gratification improves

with developmental stage (Mischel, Ayduk, & Mendoza-Denton, 2003), and can be

used as an individual difference variable to predict performance on certain cognitive

tasks (e.g., Baron, Badgio, & Gaskins, 1986). Supporting evidence shows that children

discount future rewards more steeply than young adults who, in turn, discount more

steeply than older adults (Green, Fry, & Myerson, 1994), suggesting that young people

commit more impulsive acts than do the elderly (Read & Read, 2004). Others have

conceptualized impulsivity as a stable personality trait and found that highly impulsive

individuals show higher discount rates than their less impulsive counterparts

(Ostaszewski, 1996). Verplanken and Herabadi (2001) showed that general impulse

buying tendency correlates negatively with conscientiousness and positively with

extraversion of the Big Five personality dimensions, as well as with arousal and hedonic

buying considerations (Herabadi, Verplanken, & van Knippenberg, 2009). Baumeister

and colleagues (Baumeister, 2002; Baumeister & Vohs, 2003; Baumeister, Vohs, & Tice,

2008) see individual differences in self-control failure as a powerful potential predictor

of impulsive purchasing. Hence, the common implication is that there are stable

individual differences in impulsivity which, presumably, should manifest themselves

across different types of consumer goods, in the sense that individuals who discount

more steeply than others for one type of consumer good, should also discount more

steeply for other types of goods.

These frameworks, however, need further development. None offers an account of

one of the most striking aspects of consumer impulsivity: why it is the case that certain

goods tend to be bought impulsively (such as fashionable clothes) whereas others

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 755

commonly are not (such as basic body care products). The traditional discounted utility

model would predict that temporal discounting is independent of type of consumer

good. Trait-based approaches predict stable individual differences in discounting: if

some people are more impulsive than others, then this general propensity should

manifest itself across consumer goods. In contrast, we propose a new model with three

identity-related predictors of consumer impulsivity.

A new model of consumer impulsivity

Our starting-point is that consumer impulsivity in well-developed mass consumer

societies such as the UK has to be understood in the context of the contemporary

sociocultural environment. An increasingly powerful context in which individuals

construct and express their identities is the material and consumer culture we live in.

Having the ‘right’ material goods has become vital to many, not so much because of these

things themselves, but because of hoped for psychological benefits, such as moving

closer to an ideal identity, creating a desired social image, and achieving positive

emotional states. One reason for this greater psychological significance of material goods

is that traditional, stable means of identity construction – such as community, class,

religion, family, or nationality – have become eroded, particularly in urban

environments, leading to an empty self (Cushman, 1990). Instead of being ascribed

by the kinds of contextual factors listed above, identity is increasingly achieved by

the individual her- or himself. An important element of such achieved identity is

the acquisition, ownership, and consumption of material goods, which are used

increasingly to symbolize to self and others who a person is, their actual self, and who

they would like to be, their ideal self (Dittmar, 2000, 2004a,b, 2008, in press). Our model

includes three identity-related factors that we test as predictors of consumer impulsivity. Types of consumer goods

We propose that goods which have high identity-expressive potential are more likely to

be bought on impulse than goods unlikely to serve in this fashion. Extensive qualitative

research, using a ‘favourite possessions paradigm’, analyses the reasons why people

treasure some of their material goods very highly (Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton,

1981; Dittmar, 1989, 1992, 2008, in press; Kamptner, 1991). In these accounts, it

emerges that identity construction, expression, and maintenance are powerful

psychological determinants of why material goods are important to people, with

clothes emerging as a particularly potent identity-expressive type of good. This is further

confirmed in analyses of clothes as consumer goods to be bought, as well as goods

already owned (Dittmar, 2008; Solomon, 1985). For example, in a UK community

sample, adults rated the importance of motives for buying clothes as compared to basic

body care products (such as shampoo) when they buy these types of goods on impulse,

defined as ‘a “spur of the moment” decision in the shop’. Buying motives to obtain

psychological benefits were all higher for clothes, such as improving one’s mood or

increasing one’s status, but the difference was most pronounced on the motives for

identity expression and moving closer to an ideal self (Dittmar, 2008, pp. 56–57).

Thus, clothes should make more likely targets for consumer impulsivity than goods

that have less identity-expressive potential, such as saucepans, and this has been

demonstrated in earlier studies, particularly for women (Dittmar et al., 1995). In support

of our proposal that material goods with high identity-expressive potential make more

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 756 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond

likely impulse buys than goods which do not offer such potential, we can draw on data

from our own previous research. In one study (Dittmar & Anderson, 2004), a sample

of adult employees rated different reasons why they buy and value four different

consumer goods. Means for the scale ‘express who you are, make you feel more like

your ideal’ are given in the first column of Table 1. We found that clothes have a much

stronger identity-expressive function than the other three types of goods, particularly

basic body care products and tools, with effect sizes ranging from .6 to .8.

Table 1. Identity-expressive function and impulse buying frequency of five types of consumer goods Impulse buying indexb Actual impulse buy frequency Identity-expressive functiona (among students) (per month)

(Dittmar & Anderson, 2004) (Dittmar et al., 1996) (Dittmar, 2005b) Clothes 5.0 2.13 1.57 Sports gear nac 2.09 na d Music items 3.4 2.12 e 0.39e Basic body care 2.7 2.34 0.34 Tools 2.0 naf nad

a Measured on six-point scales ranging from 1 not at al to 6 very much.

b Less negative numbers indicate relatively higher impulse buying frequency.

c This consumer good was included in the rating study.

d This type of good was not coded separately in the diary study.

e The apparent inconsistency between the index and actual impulse buy frequency is due to music items

being high-impulse goods among students, but not among older, general population samples.

f This type of good was not included in the study.

At the same time, we have data from two previous studies on how frequently these

goods are actually bought on impulse. In a study with students (Dittmar et al., 1996), we

collected indices that compare the reported frequency of buying a type of good on

impulse with the frequency of buying it in a planned fashion, such that the resulting

index varies from 2 1 to þ 1, with less negative numbers reflecting relatively greater

impulse buying. The means are given in the second column of Table 1 and show that

sports gear and clothes are types of good that, comparatively, are more likely to be

bought on impulse than basic body care products.

A third study demonstrates directly how often these types of goods are actually

bought on impulse. Respondents from a community sample completed ‘shopping

diaries’ for 1 month, recording all impulse purchases made (Dittmar, 2001, 2005b).

Clothes stood out as the single, most frequent impulse buy. Respondents bought clothes

significantly more often on impulse than basic body care items and music items (see the

last column in Table 1 for means). Taken together, the findings in the ‘favourite

possessions’ paradigm in conjunction with the data presented in Table 1 offer a sound

basis for concluding that clothes are a type of consumer good that fulfils a particularly

high identity-expressive function for individuals, and that is bought on impulse much

more frequently than goods with much lower identity-expressive potential, especially

basic body care products or tools. Thus, we expect that discount rates, and hence

consumer impulsivity, differ systematically with respect to type of consumer good. It has

not been examined previously whether identity-expressive goods are, in fact,

discounted more steeply than goods less likely to serve this psychological function.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 757 Identity deficits

Identity deficits or self-discrepancies (Higgins, 1987) are defined as the psychological

salience of perceived discrepancies between a person’s actual identity (how they are)

and their ideal identity (how they would ideally like to be). These should sensitize

individuals to the identity-expressive potential of material goods, as long as they view

material goods as suitable tools for improving one’s identity (Dittmar, in press). Identity

deficits are a psychologically uncomfortable state to be in (Gramzow, Sedikides, Panter,

& Insko, 2000), and individuals are therefore motivated to close or minimize their actual-

ideal self-discrepancies. Symbolic self-completion theory (Wicklund & Gollwitzer, 1982)

proposes that people make use of material goods, amongst other strategies, to

compensate for perceived identity deficits. Supportive evidence shows that business

students who lacked good qualifications, displayed more relevant material symbols,

such as an expensive watch, briefcase, or business suit, compared to students with

better career prospects (Wicklund & Gollwitzer, 1982). A later series of studies further

confirmed a compensatory relationship between increased use of material symbols and

lack of experience, expertise, or competence in occupational, domestic, or ideological

identity domains (Braun & Wicklund, 1989). Thus, identity deficits are seen in the

present research as a motivator of decisions aimed at reducing the gap between how a

consumer ‘is’ and ‘would ideally like to be’. However, in order for identity deficits to

impact consumer impulsivity, or discount rates, individuals need to believe that buying

material goods is a suitable compensatory strategy. In other words, it is a prerequisite

that consumers endorse a materialistic value orientation.

Endorsement of materialistic values

A person who endorses materialistic values believes that the acquisition of material

goods is a central life goal, a prime indicator of success, and a key to happiness and a

positive identity. The link between material goods and identity is a core feature of a

materialistic value orientation (e.g., Kasser & Kanner, 2004; Richins, 1995), and

materialistic individuals are particularly motivated to buy goods they think will bring

them closer to their ideal self (Dittmar, 2005a, 2007, in press). Thus, whether or not

individuals endorse materialistic values is important for consumer impulsivity because

materialism is assumed to channel an individual towards consumption as a compensatory

strategy to deal with perceived identity deficits. Indirect support for this proposal comes

from research that shows that individuals most likely to report excessive, uncontrolled

buying were both materialistic and high in identity deficits (Dittmar, 2004b). We propose

that endorsement of a materialistic value orientation is needed for identity deficits to

lead to impulse buying. For materialistic individuals, consumer impulsivity should be

greater, and hence discount rates steeper, the greater their identity deficits. For non-

materialists, identity deficits should not impact consumer impulsivity. Furthermore,

materialists’ impulsivity with respect to identity-expressive goods should be higher

when their identity deficits are made salient temporarily than when they are not. The present research

In order to test our three predictors of consumer impulsivity, we use a temporal

discounting experimental paradigm. The desire to have a consumer good right now,

rather than to have to wait, is a preference concerning outcomes separated in time,

which can be captured by a discount rate. Individuals would want compensation for

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 758 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond

delaying a desired outcome, and the amount of compensation necessary for a given

delay, as a proportion of the initial value, is the discount rate. Thus, discount rates

measure the subjective ‘cost’ of delaying immediate gratification. In the matching

paradigm of intertemporal choice methodology (e.g., Benzion et al., 1989), respondents

match the utility of a good to be consumed now (e.g., £100) with a (larger) delayed good

of the same type in the future (e.g., £X 1 year from now), by setting X such that they

are indifferent between the two choices. An annual discount rate of 50% means that

a person demanded £150 as their ‘price’ to wait a year rather than receive £100

immediately. Temporal discounting offers an appropriate experimental paradigm within

which to study consumer impulsivity, since steep discounting would push the consumer

towards immediate gratification, and the link between discounting and impulsivity has

been made by Ainslie (2005) and in a recent review by Green and Myerson (2004).

Obviously, steep discounting does not invariably lead to impulse buying, as there are

further factors involved that could prove to be barriers, such as whether one is carrying

a credit card or not to make the purchase possible, but it is a cognitive decision

concerning the good which would push the consumer towards impulse buying.

Temporal discounting can be measured in ways other than the traditional compound

discount rate outlined above. One approach uses non-linear regression to fit a

hyperbolic discount function of subjective value (e.g., Green & Myerson, 2004; Rachlin,

2006). This method is not suitable for our data for two reasons. First, because we fix

current value (you can have £10 now) and ask respondents to set the point of

indifference for a specific delay (how much would you want in 10 days’ time), in effect

holding subjective value constant and getting people to vary the amount being

discounted. Second, the hyperbolic function fits badly at the individual level, especially

when there are limited data points (as in the present research), which led Myerson,

Green, and Warusawitharana (2001) to propose the area measure as an alternative.

Notwithstanding its many advantages, this is not as good a measure for the current

experiments as the discount rate, because we choose delays that are unequally

distributed over time, in order to capture the difference between very short time delays,

1 day or 5 days, and much longer delays, such as 6 months or 2 years. The differences

between the different delays affect the contribution of respondents’ judgments to the

overall measure, so that the area measure would predominantly reflect responses to long

delays, obscuring discounting at shorter delays. Yet, it is shorter delays that are of

greatest interest in the present research.

Three sets of discount rate predictions can be derived from our model of consumer

impulsivity. The first is that discount rates will differ systematically, depending on the

type of consumer good, such that rates are steeper for goods with high identity-

expressive potential (Studies 1–3). Second, discount rates for such goods will be related

systematically to a person’s stable identity deficits, but only if they endorse materialistic

values (Study 2). Third, and finally, making identity deficits temporarily salient for

materialistic individuals will increase their discount rates for a good that typically has

high identity-expressive potential (Study 3). STUDY 1

The two aims of this first study were to (a) test a methodological innovation that

makes it possible to adapt the matching technique of the temporal discounting

paradigm to the study of different consumer goods and (b) to provide an initial

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 759

demonstration that discount rates differ systematically, depending on whether goods

are seen as having high or low identity-expressive potential (see Table 1), thus

addressing the first prediction of our model.

This study adapts the intertemporal choice matching paradigm by using vouchers for

different types of shop, which sell either goods with high identity-expressive potential

(such as fashionable clothes) or goods not likely to be identity expressive (such as basic

body care items like shampoo or nail clippers). In a repeated measures experimental

design, respondents are asked to imagine a particular kind of shop and the goods it sells

as vividly as possible, and then match the value of a voucher to be consumed now (e.g.,

£50) with a (larger) voucher that can be consumed only after a specified delay (e.g., £X

in 5 days time) by setting X such that they are indifferent between the immediate and

the delayed voucher. Money was included in addition to consumer goods. In order to

check whether this voucher adaptation is successful, we also assessed two well-

documented characteristics of discount rates, magnitude, and delay effects (Chapman,

1998; Green & Myerson, 2004), where individuals’ discount rates are higher for smaller

amounts of money, and for shorter delays.

Thus, the first hypothesis for Study 1 (1a) concerns two commonly observed

properties of discount rates, drawn from the earlier literature, whereas the second (1b)

addresses the first prediction of the proposed model of consumer impulsivity.

Replicating commonly found properties of discount rates is important in order to

validate our adaptation of the matching paradigm from money to different consumer goods through vouchers. Hypothesis 1a:

Discount rates will show a magnitude effect (with smaller rates for larger

amounts of money), and a delay effect (with smaller rates for longer delays). Hypothesis 1b:

Discount rates will differ depending on the type of consumer good, such that

they are steeper for goods with high identity-expressive potential (clothes, sports gear) than for

goods low in that respect (basic body care products). Method Participants

The sample consisted of 100 undergraduate students at the University of Sussex (UK),

studying for a variety of degrees.

Stimuli, materials, and procedure

The task was presented on computer and participants were run individually. The

program started by explaining the matching task and presenting a trial item for a

consumer good not included in the study proper. After ‘Life often makes us choose

between something nice NOW, and something even nicer, but LATER’, the trial item ran as follows:

Imagine that you win a prize in a shop that sells shoes that you really like. The prize is a

voucher to spend £75 on shoes in the shop, right now. Think about all the shoes you could

buy. Imagine yourself wearing them, and how they would feel on you.

Now imagine that you could swap this voucher for a (more valuable) voucher for the same

shop, but that you would not be allowed to spend it for 3 weeks.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 760 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond

How much would the bigger voucher have to be worth so that you didn’t care whether you

got the £75 voucher now or the bigger voucher in 3 weeks?

(Respondent asked to enter an amount in full pounds Sterling).

In addition to making the matching task as transparent as possible, the wording was

intended to increase experimental realism and keep the respondent’s interest by inviting

them to imagine themselves as vividly as possible inside the shop and using the goods in

question. As soon as the respondent completed the trial item correctly (by entering an

amount exceeding £75), they started on the study proper, which asked them about

money and three types of consumer goods: clothes, sports gear, and body care products.

The delays were 5 days, 1 month, 6 months, and 2 years, and the amounts used were £10,

£50, and £200. In total, each respondent made 48 judgments. The items were presented

in blocks, containing all amount and delay combinations for one particular type of good,

and the wording introducing each new type of shop was the same as that given for the

trial item (e.g., … sells clothes that you really like … imagine yourself wearing

them … ). The order of blocks, as well as amounts and delays within a block, were

randomized to counteract order and fatigue effects. After each item, respondents

entered the amount of money needed for them to wait in full pounds Sterling. Results

Discount rates were calculated, according to a standard formula (e.g., Benzion et al., 1989), as r ¼ ðv = d v0Þ1=d 2 1:

where vd is the amount of money that the respondent entered as a ‘compensation price’

for having to wait, v0 is the magnitude of the immediate (voucher) money value, and d is

the delay in days between the two. Responses that implied negative discount rates, in

that the delayed value was less than the immediate value, were dealt with in one of two

ways. Four respondents were omitted from the analysis for making more than five such

responses, on the grounds that they had either not understood the task or had

responded randomly. Other than this, such errors occurred very rarely (in less than 1%

of responses) and appeared to be errors in keying in the answer (e.g., £30 to wait 2 years

for an immediate £200 clothes vouchers, instead of £300); based on agreement between

two independent judges of the intended answer, their judgment was substituted for the

original response (in this case £300 instead of £30).

Overall, the discount rates we obtained typically were very high (particularly in

Study 2 reported later). However, the few studies that have used delays as short as ours

report comparable, or even higher, rates (e.g., Kirby, 1997). As in previous studies

(e.g., Loewenstein, 1988), the substantial positive skew of the response distribution was

normalized through natural logarithm transform. The log-transformed discount rates

were analysed by a 4 (three types of good and moneyÞ £ 3 ðmagnitude of

amountÞ £ 4 ðlength of delay) ANOVA with repeated measures on all factors, including

a trend analysis on amount and delay. We found significant magnitude and delay effects

consistent with Hypothesis 1a. Discount rates decline with increasing amount of money,

Fð1; 95Þ ¼ 969:29; p , :001; h2 ¼ :91, and they also decline steeply with delay length, p

Fð1; 95Þ ¼ 1; 471:31; p , :001; h2 ¼ :94. The interaction between amount and delay p

showed that the steepness of discounting curves over time is greater for smaller than

larger amounts of money, Fð1; 95Þ ¼ 75:53; p , :001; h2 ¼ :44. p

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 761

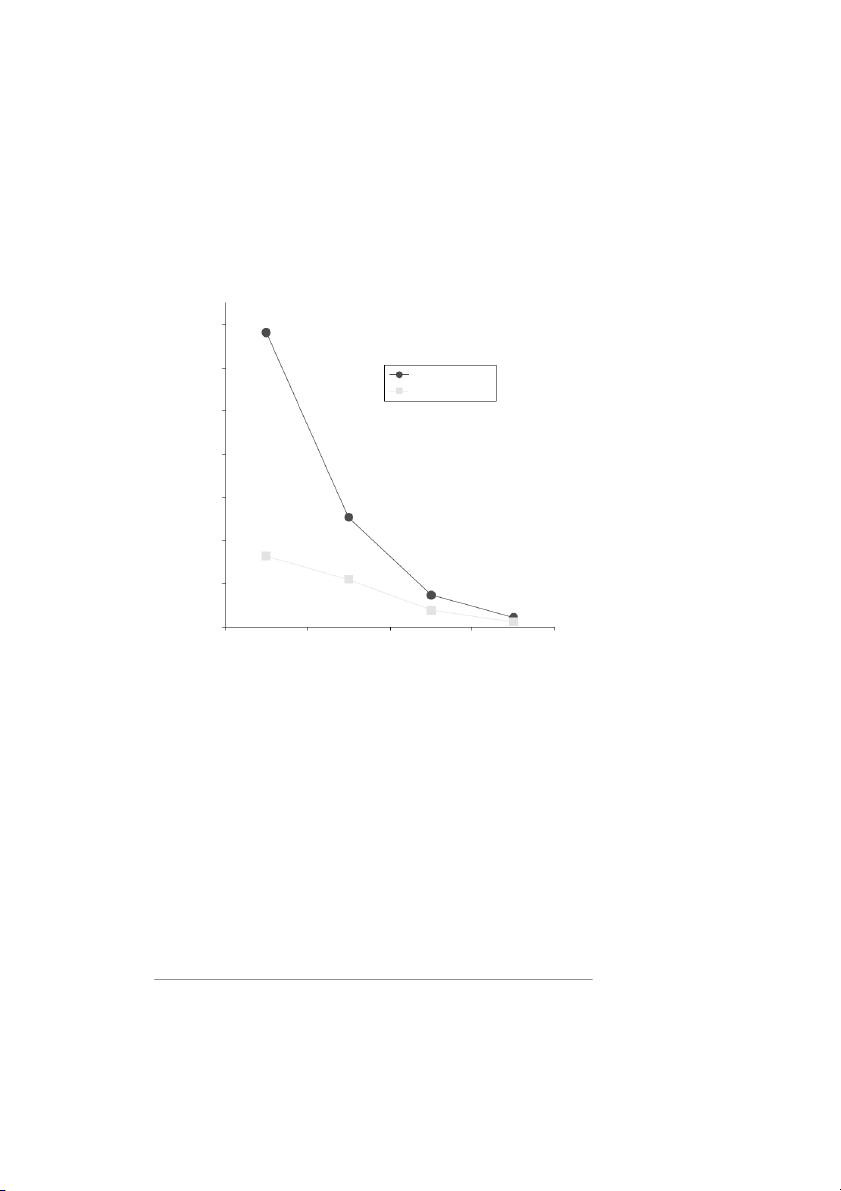

The role played by type of good was examined by three a priori orthogonal contrasts

with the first contrast central to testing Hypothesis 1b. Discount rates for the two types

of highly identity-expressive goods were compared with those for body care items. This

was followed by comparisons between the two identity-expressive goods, and between

money and the consumer goods taken together. Of central importance is the predicted

finding that discount rates differ significantly by type of consumer good,2 such that rates

were significantly steeper for the identity-expressive goods (clothes and sports gear)

than for non-expressive goods (body care products), Fð1; 95Þ ¼ 14:14; p , :001;

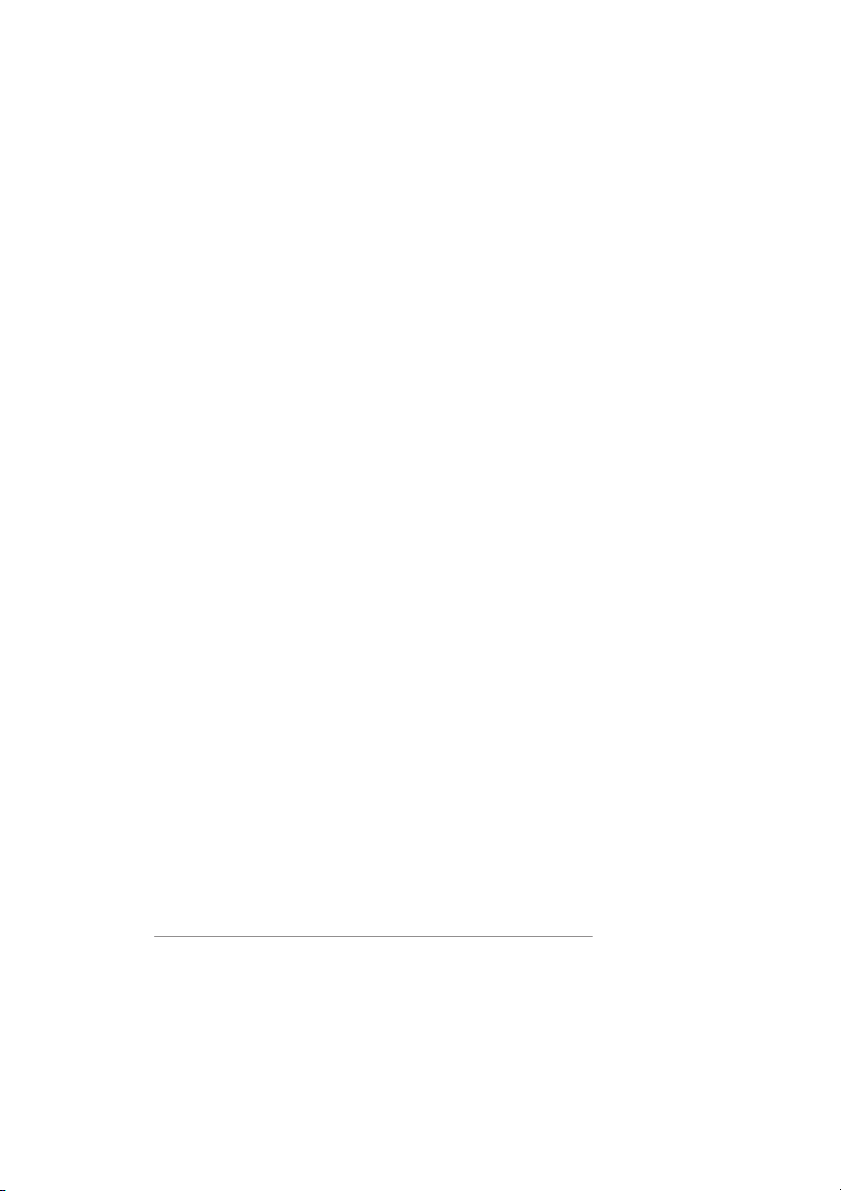

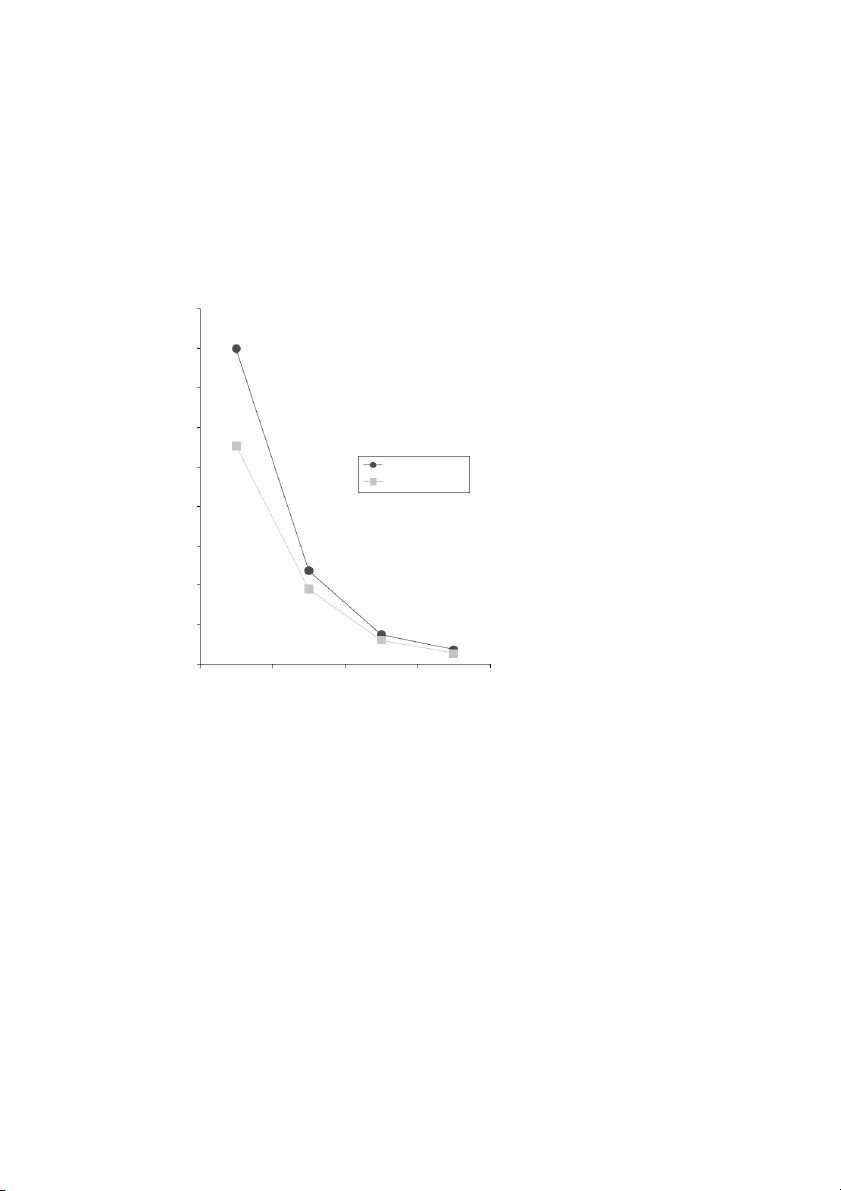

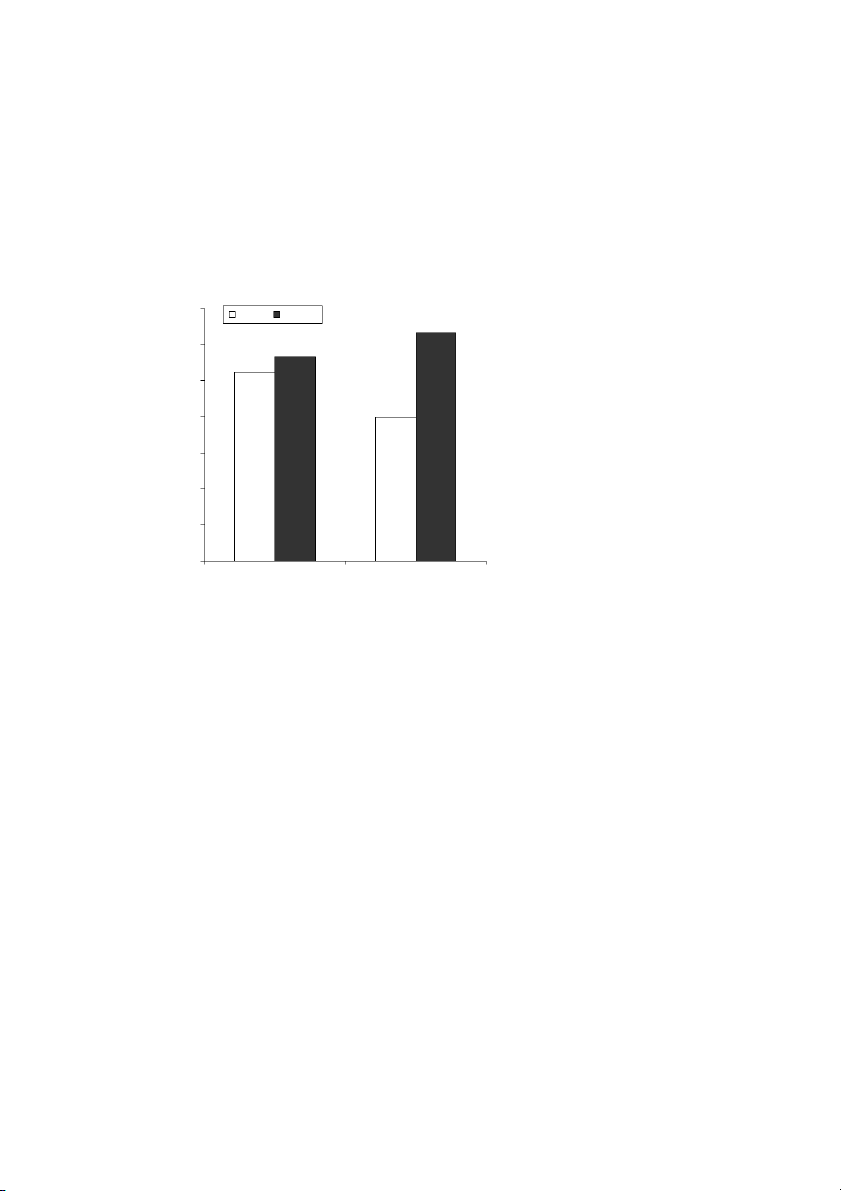

h2 ¼ :13. Geometric means of daily discount rates for these different consumer goods p

are shown in Figure 1. In addition, the results for the second contrast show that clothes

were discounted even more steeply than sports gear, Fð1; 95Þ ¼ 9:09; p , :01; h2 ¼ :09, p

whereas the third contrast comparing money with the average across the consumer

goods was not significant, Fð1; 95Þ ¼ :92; ns. Discussion of Study 1

The magnitude and delay effects replicate hallmark characteristics of discount rates

commonly reported in the literature (Frederick et al., 2002; Green & Myerson, 2004). This

lends credence to the validity of our adaptation of the experimental matching paradigm,

which used vouchers for consumer goods as a methodological innovation. The central

finding that supports the first prediction of the proposed model of consumer impulsivity

is the systematic difference in discount rates between different types of consumer goods.

Respondents demanded significantly more compensation to wait for goods high in

identity-expressive potential, compared to a type of good that does not offer this

potential. Clothes were the consumer good that was most steeply discounted. Thus, the

proposal that discount rates are dependent on the type of consumer good was strongly

supported, which suggests stronger impulsivity with respect to goods that have high

identity-expressive potential, and these also make typical impulse buys.

The finding of the expected differential discount rates for high- and low-

identity-expressive goods is encouraging, but confidence would be strengthened by a

replication, preferably in a non-student sample. Furthermore, assuming that the

differential discount rates replicate, the second prediction of the proposed model of

consumer impulsivity needs to be addressed: that discount rates for identity-expressive

goods are related systematically to consumers’ identity deficits, as long as they endorse

a materialistic value orientation. STUDY 2

This study had two aims. The first was to replicate the finding that discount rates differ

between consumer goods in a sample of adult consumers. Adult consumers are likely to

have higher incomes than students, more opportunities for impulse buying, and

possibly a greater diversity in terms of consumer impulsivity. The second aim was to test

whether discount rates can be predicted from individuals’ identity deficits, if they

endorse materialistic values. For materialistic individuals, but not non-materialists,

2 Two-way interactions between type of good and magnitude or delay, as wel as three-way interactions were significant, but

with smal effect sizes (largest h 2 ¼ :04, and more than half # :03). p h 2p

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 762 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond 4.5 4 3.5 3 te t ra n 2.5 Identity-expressive u Non-expressive isco d % 2 ily a D 1.5 1 0.5 0 5 days 1 month 6 months 2 years Delay

Figure 1. Discount rates of identity-expressive versus non-expressive goods at different delays (Study 1).

we expect that their discount rates increase as a function of greater identity deficits, but

only for goods classified as having high identity-expressive potential, such as clothes.

The specific hypotheses examined were: Hypothesis 2a:

Discount rates for the identity-expressive good, clothes, will be steeper than for

the less identity-expressive goods, body care products, and music items (replication of Study 1). Hypothesis 2b:

For the identity-expressive good, clothes, but not the other goods, discount

rates will correlate positively with the extent of a person’s identity deficits, but only if they endorse materialistic values. Method Participants

The sample consisted of 60 adult consumers, who had participated in a larger mail survey

(Dittmar, 2004b, 2005b). They volunteered to take part in this study as part of several

follow-up investigations, for which they received a payment of £10. In terms of consumer

behaviour, the sample was heterogeneous, including some individuals who had contacted

a self-help organization because they lacked self-control in their buying behaviour.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 763

Stimuli, materials, and procedure

This study was also computer-run and very similar to Study 1. In addition to money,

clothes and body care products were examined as high- and low-identity-expressive

goods, respectively, as in Study 1, but music items were included as a second good

comparatively low on identity expression potential among this older community

sample. The amounts of voucher money remained the same – £10, £50, and £200 – but

we decided to add an unusually short delay 2 1 day – in order to be able to tap into

extreme consumer impulsivity that may manifest itself most strongly for a very short

time horizon. In order to keep the length of the experiment manageable, we deleted the

2-year delay used in Study 1, leaving four delays: 1 day, 5 days, 1 month, and 6 months.

Again, items were presented in blocks comprising all amount and delay combinations

for one particular type of good, randomized to counteract order and fatigue effects. Each

respondent made 48 judgments in total, completing the experiment in their own home

on a laptop computer brought by the researcher. They were asked afterwards to

comment on their experience of the discounting task.

Respondents’ identity deficits and materialistic values had been measured in the

larger mail survey in which these respondents had already participated (Dittmar,

2005a,b). We used our own measure of identity deficits, first described in Dittmar et al.

(1996), validated in Halliwell and Dittmar (2006), and discussed in detail in Dittmar

(2008, in press). It consists of a participant-generated self-discrepancy index (SDI),

which asks respondents to complete up to five sentences, of the format ‘I … … … , but I

would like … … ,’ using any word or set of words they liked, and then to rate each self-

discrepancy they generate in terms of its magnitude (size of discrepancy) and

psychological importance (concern or worry about the discrepancy), using five-point

Likert type scales ranging from not at all (1) to very much (5). As a global measure of

identity deficits, SDI is calculated by summing the products of the magnitude and

importance ratings of each self-discrepancy and then dividing by the number of

statements (Dittmar, in press). Thus, X h i =n; SDI ¼ I £ i D

where Ii is the importance of attribute i, Di is the distance between actual and ideal self

on attribute i, and n is the number of sentences completed. SDI scores could range from 1 to 36.

Materialistic value endorsement was assessed by an established and validated scale

(Richins & Dawson, 1992) that showed excellent internal reliability (a ¼ :87). Example

items are ‘One of the most important achievements in life includes acquiring material

possessions’ and ‘I would like to own things that impress people’. Using a criterion

score close to the theoretical scale mid-point (established in the full survey sample of UK

consumers, 2004b3), respondents were classified as either endorsing materialistic

values (n ¼ 39) or not (n ¼ 18). This means that those classified as endorsing

materialism on average agreed with the scale items, whereas those who were classified

as non-materialists on average disagreed with the scale items. We are aware that using a

continuous measure of a variable is usually preferred to a dichotomous split, but we

3 This survey had 330 respondents, diverse in educational qualifications, occupation, and income, thus offering a more

empirical y sound basis for classifying research participants as materialists or not than the smal er sample of respondents in the

present research, whose agreement to take part in fol ow-up studies is likely to indicate interest in consumption. The cut-off point

was both close to the empirical median split in the survey, 3.3, and to the theoretical mid-point of the materialism scale, 3.5.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 764 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond

chose this strategy for two reasons. First, tests of interaction with continuous survey

measures, such as our materialism scale, often have less than 20% of the efficiency of

optimal experimental tests in detecting interaction effects (McClelland & Judd, 1993).

Second, our predictions are highly specific, such that we expect a positive correlation

between identity deficits and discount rates only in a particular subgroup of

respondents (those who can be said to have endorsed materialistic values) and for only

one type of consumer goods, clothes, which is unlikely to be reflected in an overall interaction term. Results

Log discount rates were calculated as in Study 1, and the very high discount rates for

short delays in the first study were also found here, particularly for the even shorter

delay of 1 day. The data of three individuals were omitted from the original sample of

60 according to the exclusion criteria employed in Study 1. The data were analysed by a

4 (three types of good and moneyÞ £ 3 (amount) by £ 4 (delay) repeated measures

ANOVA.4 Highly significant findings for the magnitude and delay effects again replicate

the commonly reported characteristics of discount rates also found in Study 1: steeper

discounting with smaller amounts, Fð1; 54Þ ¼ 193:76; p , :001; h2 ¼ :78, with shorter p

delays, Fð1; 54Þ ¼ 83:80; p , :001; h2 ¼ :61, and their interaction, Fð1; 54Þ ¼ 7:87; p p , :01; h2 ¼ :13. p

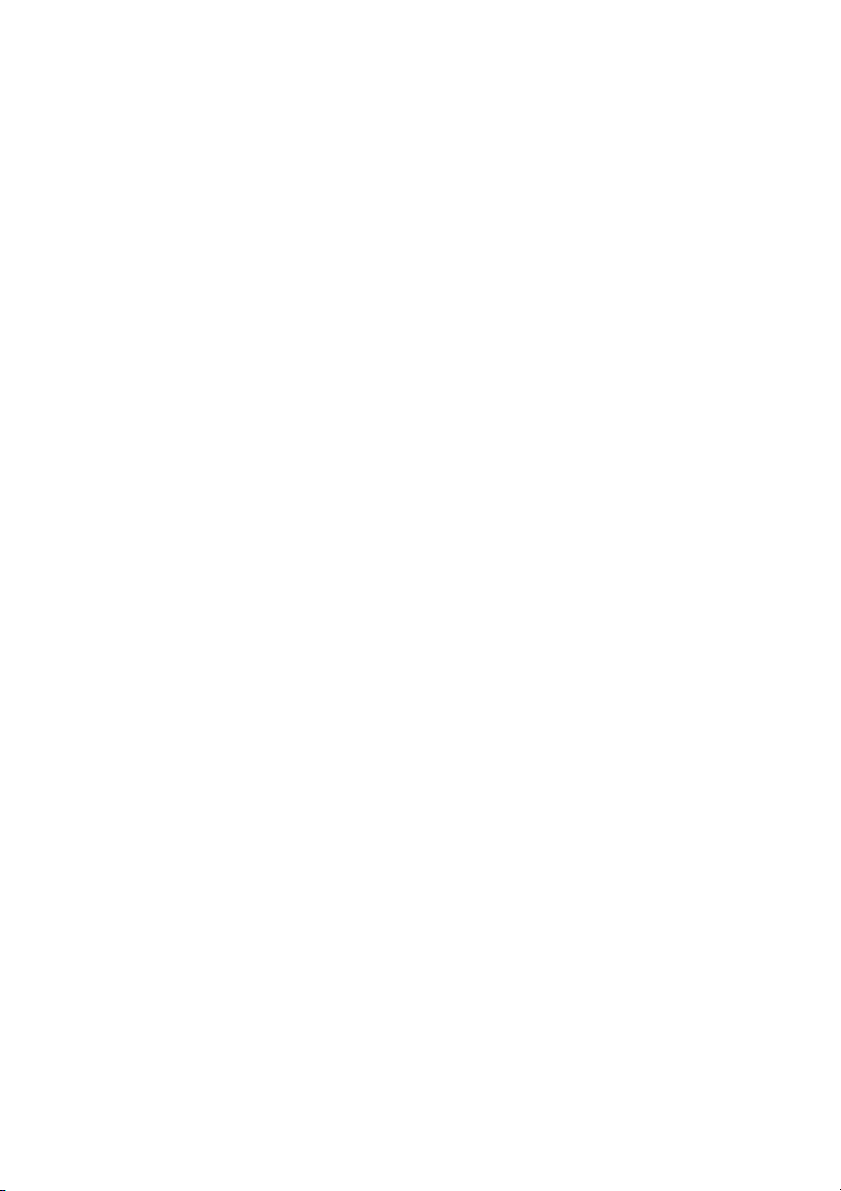

The role of different types of goods was again assessed by three a priori orthogonal

contrasts similar to those used in Study 1. The first compared discount rates for the

identity-expressive good, clothes, with the less expressive goods, body care, and music

items. The second compared the two less expressive goods, and the third compared

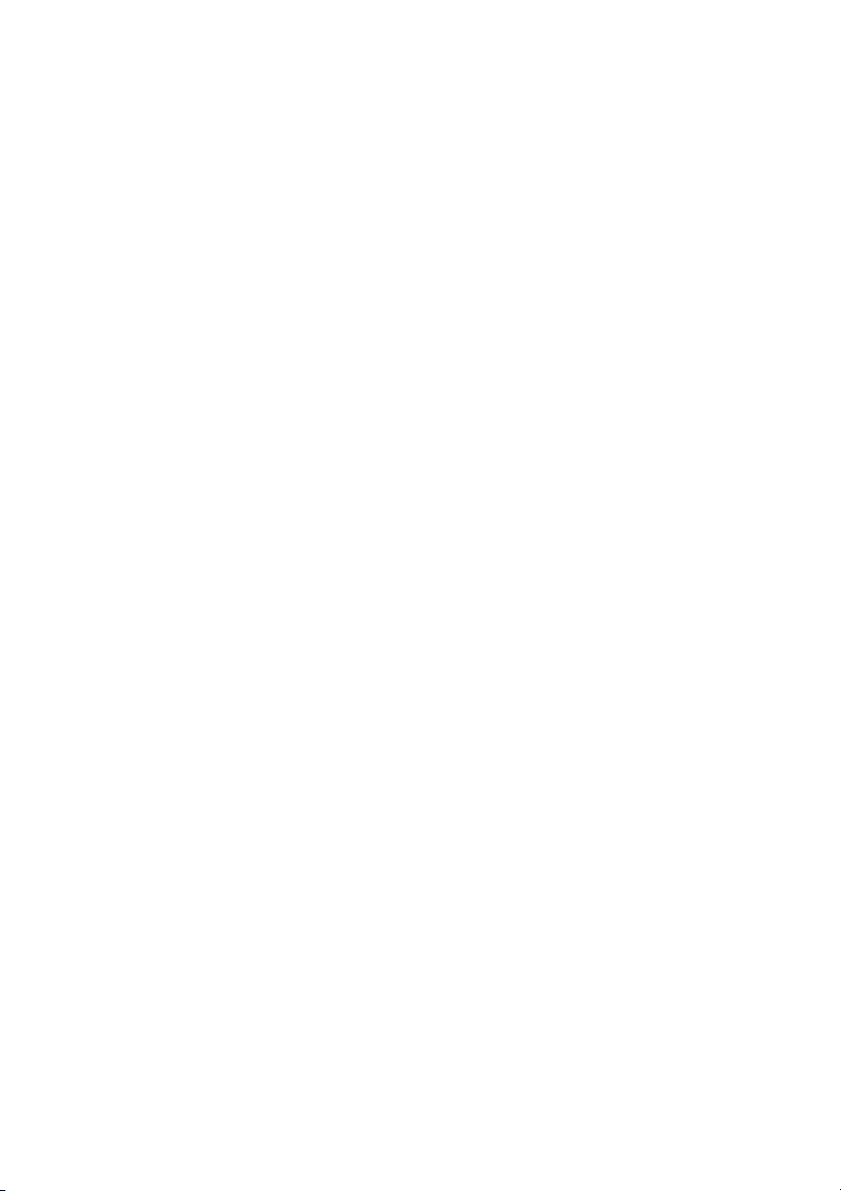

money with all three consumer goods combined. Consistent with Study 1 and

supporting the first hypothesis, discount rates differed significantly by type of consumer

good, such that rates were steeper for the identity-expressive good than for the other

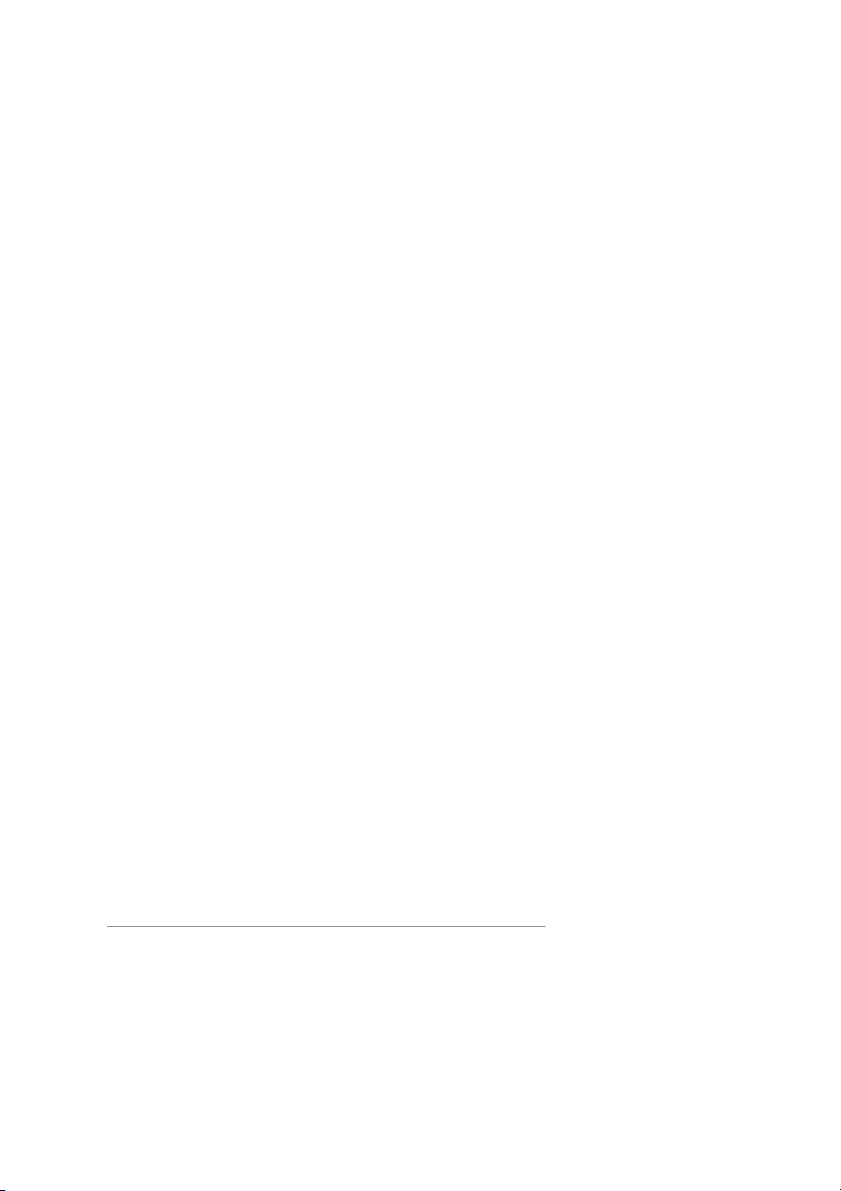

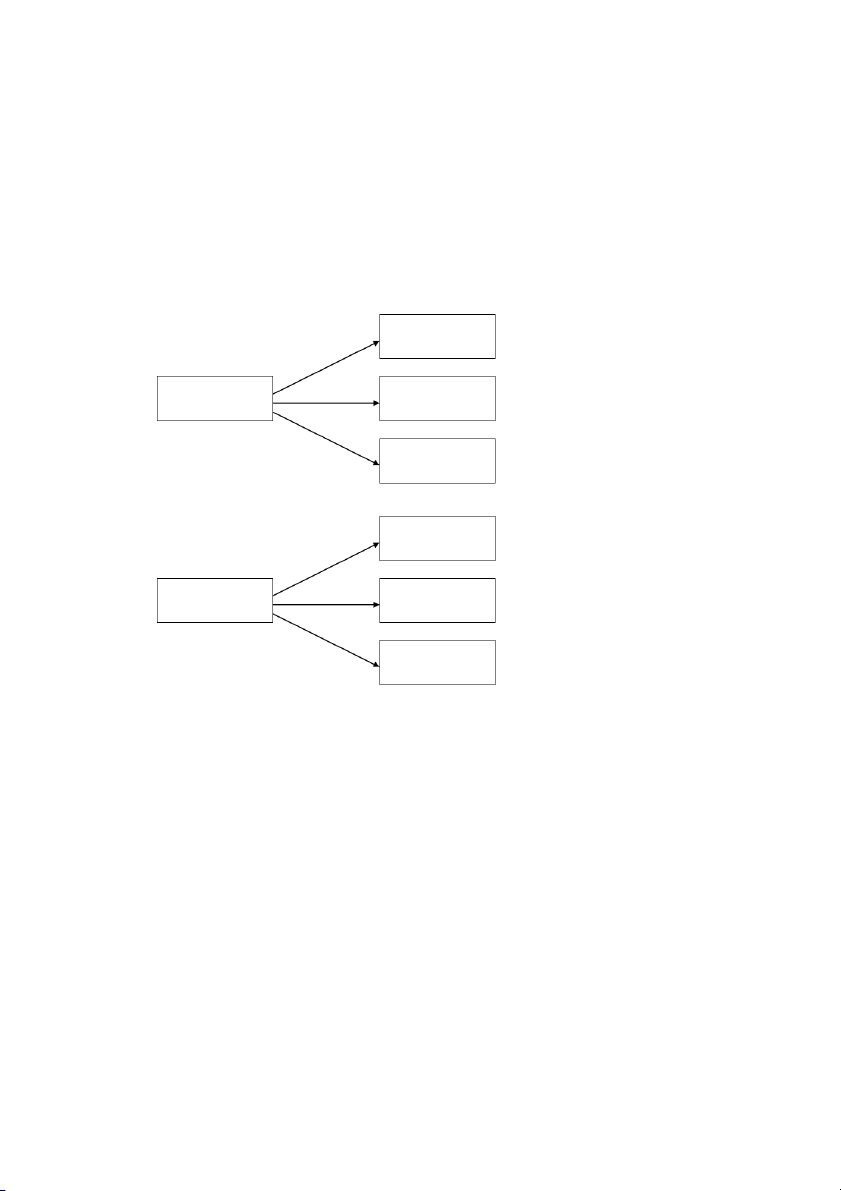

goods, Fð1; 54Þ ¼ 12:83; p , :001; h2 ¼ :19. Geometric means are shown in Figure 2. p

The effect size was larger than in Study 1, and this may mean that adult consumers

discriminate more strongly between these different types of goods compared to

students. Music items and body care products did not differ significantly from each

other, Fð1; 54Þ ¼ 3:12; ns. In contrast to Study 1, money was discounted more steeply

than consumer goods, Fð1; 54Þ ¼ 13:65; p , :001; h2 ¼ :20.5 Thus, the central finding p

is that discount rates were higher for the type of good that has high identity-expressive

potential than for types of goods that are less expressive of identity. This provides

support for Hypothesis 2a and replicates the student results in this more heterogeneous adult sample.

We now turn to the second central question addressed in Study 2, which entails

a highly specific prediction of elevated discount rates. We expect that, for the

identity-expressive good, clothes, discount rates should be correlated positively with

the extent of a person’s identity deficits, but only if they endorse materialistic values.

4 Gender and whether individuals had been recruited via the buying behaviour self-help organization were also examined, but

did not yield systematic findings of interest for the present research.

5 In addition, two significant interaction effects were found for the contrast between goods high and low in identity-

expressive potential, showing that steeper discounting for short delays is amplified for identity-expressive goods,

Fð1; 54Þ ¼ 4:63; p , :05; h2 ¼ :08, particularly in conjunction with vouchers for a smal er amount, Fð1; 54Þ ¼ 6:36; p p , :05; h 2 ¼ :11. p

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 765 14 12 Identity-expressive Non-expressive 10 te t ra n u 8 isco d % ily 6 a D 4 2 0 1 day 5 days 1 month 6 months Delay

Figure 2. Adult consumers’ discount rates for identity-expressive versus non-expressive goods at different delays (Study 2).

For non-materialists, identity deficits should not be related to discount rates for this, or

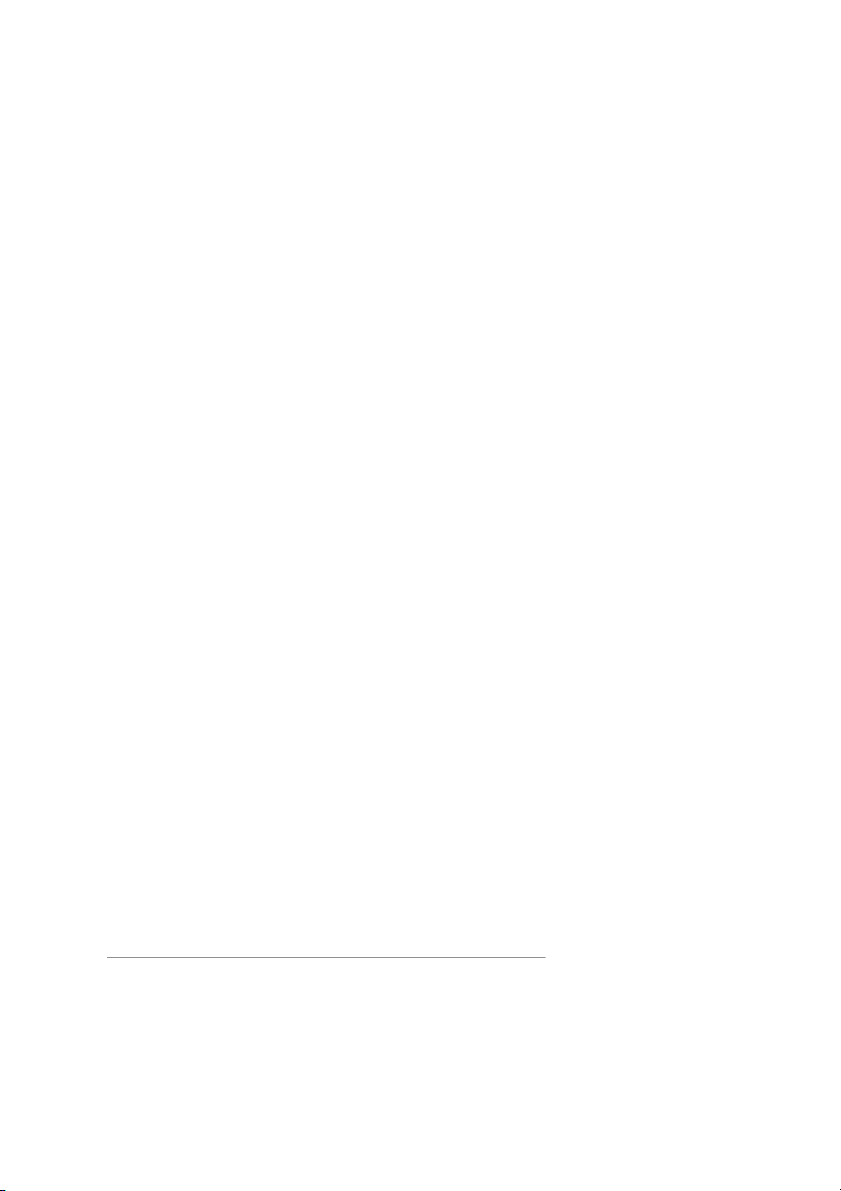

any, type of good. Figure 3 shows the correlations between identity deficits and discount

rates,6 separately for materialists and non-materialists. For materialists, there was a

significant correlation, r ¼ :32, between their identity deficits and the discount rate

for clothes, whereas this correlation was close to zero for non-materialists, r ¼ :03.

Constraining these correlations to be equal in a two-sample structural equation model

resulted in a significantly worse model fit, Dx2ð1Þ ¼ 4:72, p , :01, indicating a

significant difference between them. As predicted, identity deficits were not signifi-

cantly correlated with discount rates for the less expressive goods, body care, and music

items, either for materialists or non-materialists. Thus, Hypothesis 2b was supported. Discussion of Study 2

Overall, the results of Study 2 replicated those of Study 1 with respect to discount rates,

and hence consumer impulsivity: discount rates were higher for a type of good that is

highly expressive of identity, clothes, than for less expressive goods. Findings also

6 The patterns of associations were similar in the different delay and amount conditions.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 766 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond Materialists Clothes .32** Identity deficits –.01ns Music items –.02ns Body care products Non-materialists Clothes .03ns Identity deficits .03ns Music items –.19ns Body care products ** p<.01

Figure 3. Correlations between materialists’ and non-materialists’ identity deficits and discount rates

for different types of consumer goods.

provide direct support for the proposal that discount rates for identity-expressive goods

can be predicted from a person’s materialistic value endorsement and identity deficits.

For materialistic individuals, higher identity deficits are systematically related to

demanding higher compensation for waiting to consume an identity-expressive good,

clothes, but not less expressive goods. As predicted, individuals who do not endorse

materialist values showed no links between discounting and identity deficits.

Possible criticisms of the discounting methodology we employed could be that the

task may be artificial, or that discount rates are not directly related to actual consumer

decision making in retail environments. However, the follow-up, where respondents

commented on their experience of the discounting task, showed that less than 4% found

the task boring or meaningless, and several respondents reported excitement, and even

physiological reactions, such as raised heart beat, confirming that our sample had

engaged with the task and took it seriously. More importantly, with respect to actual

decision making in shops, it was possible to calculate correlations between individuals’

discount rates for clothes and the frequency with which they had actually purchased

clothes impulsively in the previous month, as recorded in the separate shopping diary

study. Despite the short time span of the diaries (1 month), there are significant

correlations between respondents’ total number of impulse purchases of clothes and

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 767

discount rates at both 1 month’s delay, r ¼ :30; p , :05, and 6 months’ delay, r ¼ :33;

p , :05. Thus, there is good evidence that those who have higher discount rates in this

study are actually more likely to have made impulsive purchases of that type of good during the previous month.

Finally, this study examined identity deficits as a stable individual difference variable

and found, as predicted, systematic links for materialistic individuals between the extent

of their identity deficits and consumer impulsivity for a type of good that is typically seen

as offering high identity-expressive potential. Yet, perceived identity deficits can

fluctuate to some extent depending on context (e.g., Boldero & Francis, 2000; Dittmar,

Halliwell, & Stirling, 2009); people feel better about themselves at certain times and

worse at others. This suggests that implications of the proposed model could be tested

further through an experimental manipulation of temporary identity deficit salience. STUDY 3

Two main aims guided this final study. The first was to replicate again that there are

differential discount rates for different types of consumer goods. In this instance, we

decided to compare clothes, as a typical identity-expressive good, with a new low-

expressive good that may be more similar to clothes than basic body care products in

terms of unit price and likely time course of consumption. It was decided to use tools for

home and garden (e.g., tool kit, cordless drill) because tools are more costly than many

body care items and are consumed over a longer period of time, making them more

comparable to clothes on these dimensions. As already reported (see Table 1), tools are

not used for identity expression, in contrast to clothes. The second aim of this study was

to test whether a manipulation of the salience of materialistic individuals’ identity

deficits would impact on the discounting of identity-expressive goods. In the previous

study, perceived identity deficits were examined as a stable individual difference, but

they can also be examined as a temporary construct (Dittmar & Halliwell, 2005; Dittmar,

Halliwell, & Stirling, 2009). Such a conceptualization is consistent with evidence related

to self-discrepancy theory that shows that temporarily accessible constructs can have a

stronger influence on information processing than chronically accessible constructs

(Bargh, Lombardi, & Higgins, 1988). Asking respondents to list identity deficits can be

justified as a valid manipulation of their temporary salience, given that we have

demonstrated that completing the SDI leads respondents to focus on subjectively

meaningful gaps between their actual and ideal self (Halliwell & Dittmar, 2006).

Temporarily aroused identity deficits are a good predictor of momentary negative affect,

with negative affect a well-documented consequence of self-discrepancies (Dittmar,

Halliwell, & Stirling, 2009). Thus, we expect that heightened salience of identity deficits

would lead individuals to experience greater impulsivity, reflected by higher discount

rates for goods useful for expressing and improving one’s identity, provided they endorse

materialistic values and therefore use consumption as a deficit-reduction strategy.

Respondents for the present study were volunteers from the consumer panel of a

large, multinational manufacturer of consumer goods. The sample was women, with

clothes and tools as the two consumer goods examined, which differ strongly in their

identity-expressive potential (see Table 1). The salience manipulation of identity deficits

was simple and mild. Half the respondents were asked to complete the SDI directly

before the discounting task, and the other half afterwards. Thus, for half of the

respondents identity deficits were made salient when they considered compensation for

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 768 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond

having to wait to obtain clothes and tools, but not for the other half. There were two hypotheses: Hypothesis 3a:

Discount rates will be higher for the identity-expressive good (clothes) than for

non-expressive good (tools), replicating Studies 1 and 2. Hypothesis 3b:

Making identity deficits salient will have a systematic impact on discount rates for

the identity-expressive good (clothes) compared to the non-expressive good (tools), but only

for materialistic individuals. Specifically, materialistic individuals are expected to report a greater

difference in discount rates between the clothes and tools when identity deficits are salient than when they are not salient. Method Participants

The sample consisted of 72 women who volunteered to take part in this study while

serving on the consumer panel of a multinational manufacturing company, half in the

high (n ¼ 34) and half (n ¼ 33) in the low identity deficits salience condition.

Stimuli, materials, and procedure

In order to enable data collection in the company, the discounting methodology had to

be adapted from being computer-run to questionnaire-based. Vouchers were valued at

£50 and £200 at each of four delays, 1 day, 5 days, 1 months, and 6 months, resulting in

eight items per type of good. Respondents considered one item at a time, which was

ensured through individual administration and concealment of later items. As in Studies

1 and 2, items were presented in a block for clothes and for tools and, within each block,

respondents completed the items in a fixed order (which had been randomly

determined). They then completed the same materialism scale as used in Study 2

(Richins & Dawson, 1992; a ¼ :72).

Half the respondents completed the SDI before the discounting task and half

afterwards.7 Thus, in the salient condition, they reported identity deficits directly

before discounting consumer goods, whereas they reported identity deficits afterwards

in the non-salient condition. Self-discrepancies were assessed as in Study 2, by the SDI,

that asked respondents to complete five open-ended sentences concerning aspects that

they would like to change about themselves, and then rate each self-discrepancy in

terms of its magnitude and importance. Results

Five participants were omitted from the original sample of 72 (see Study 1 for a

description of exclusion criteria). With respect to replicating the findings of Studies 1

and 2, discount rates were first analysed by a 2 (type of good ) £ 2 (magnitude) £ 4 (delay)

ANOVA with repeated measures on all factors. Magnitude and delay effects replicated

7 In order to make the two conditions more comparable, we included a further task that also involved participants in thinking

about the self, but would prevent them from considering shortcomings in their self-concept. Respondent simply wrote down

‘five things that you like about yourself ’.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 769

again, such that steeper discounting was found for the lower voucher amount,

Fð1; 66Þ ¼ 95:91; p , :001; h2 ¼ :59, and at shorter delays Fð1; 66Þ ¼ 32:53; p , :001; p

h2 ¼ :33. Of central importance is the significant main effect for type of consumer good, p

with discount rates steeper for clothes than for tools, as predicted, Fð1; 66Þ ¼ 13:10;

p ¼ :001; h2 ¼ :17. The mean daily discount rate for clothes was 1.09%, compared to p

0.84% for tools. Thus, the finding that a type of good that affords identity expression is

discounted more steeply than a non-expressive good replicated once again. The close

match between clothes and tools in unit cost and time course of consumption adds

confidence to the robustness of this effect.

In order to examine the effect of experimentally manipulating the salience of identity

deficits on discount rates, a single SDI score was calculated as in Study 2. There was no

systematic difference in SDI score between respondents in the two salience conditions,

tð65Þ ¼ 21:17; ns, thus excluding the possibility that pre-existing differences in identity

deficits between individuals allocated to the salient versus non-salient condition could

account for differences in discount rates.

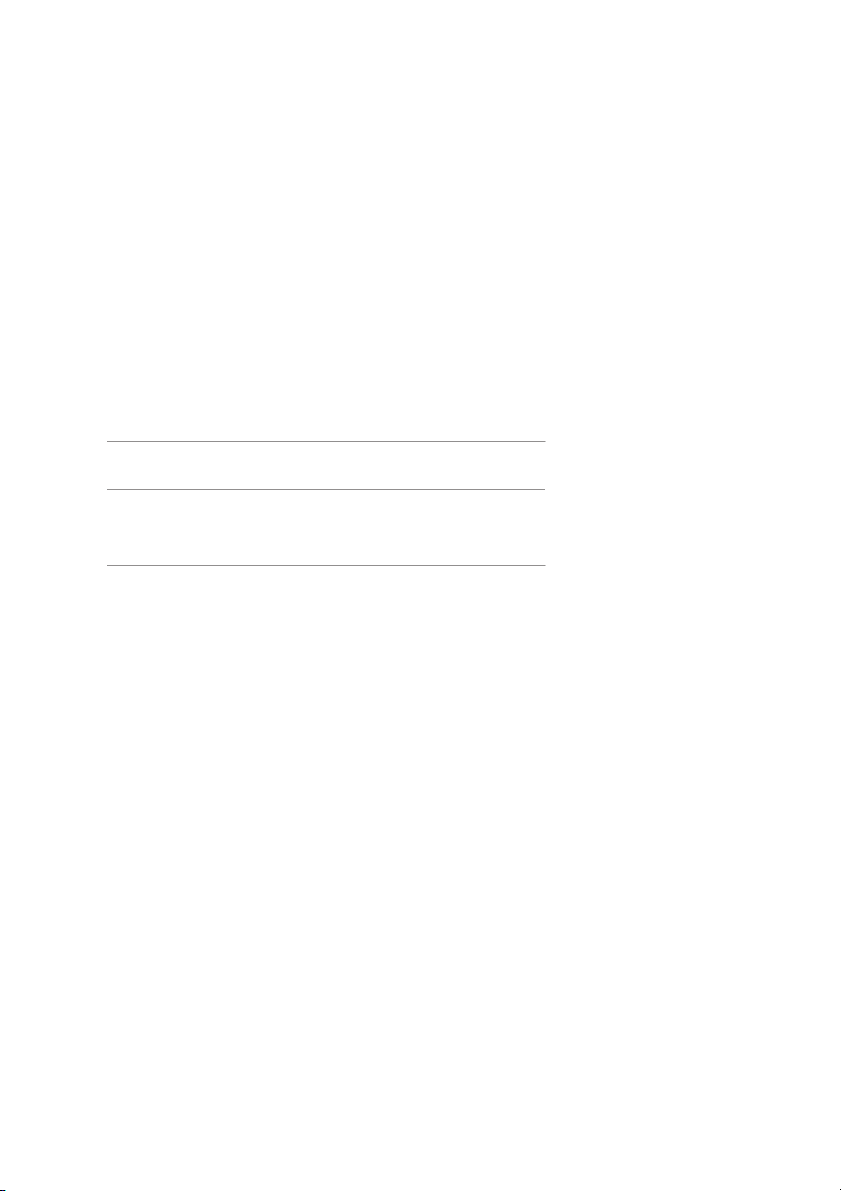

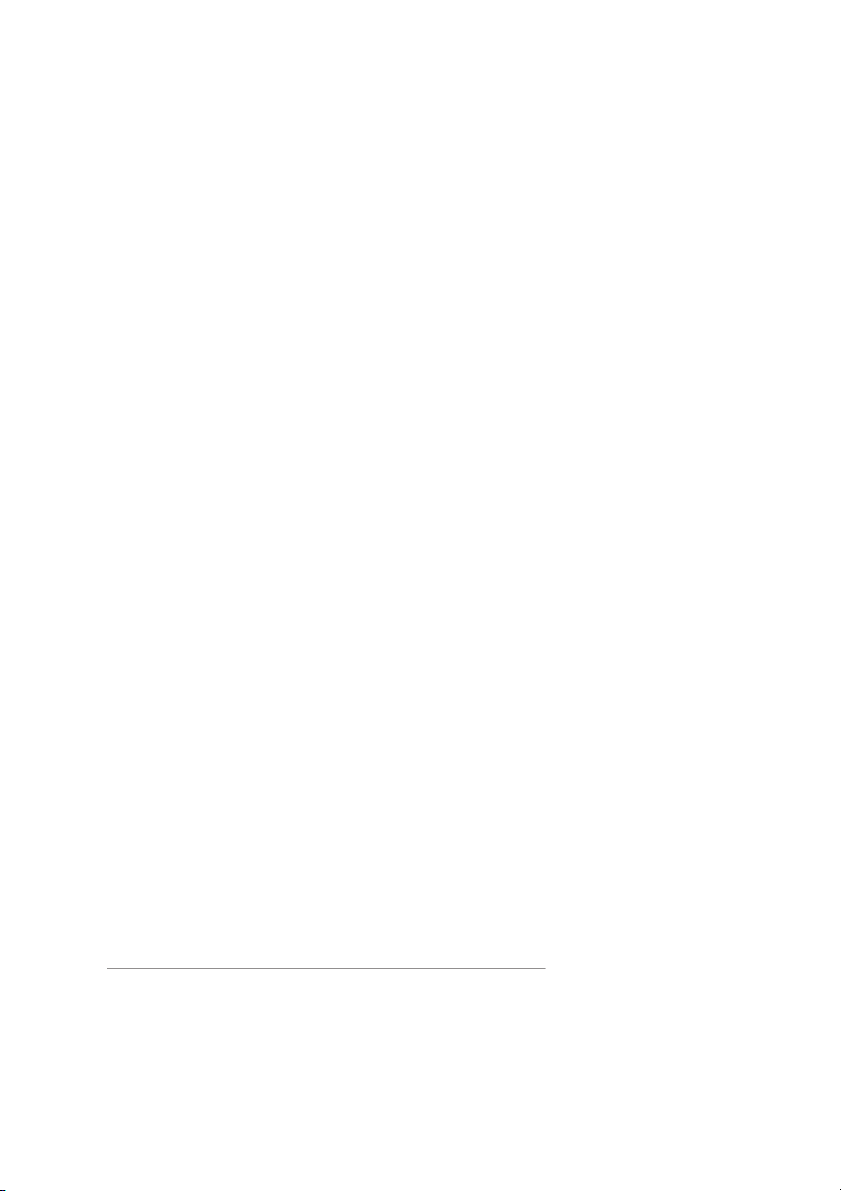

In order to test Hypothesis 3b, which predicted an interaction effect between type of

good and temporary salience of identity deficits only for materialists, analyses were

run separately for individuals with (n ¼ 47) and without (n ¼ 20) endorsement

of materialistic values (using the same classification as in Study 2). Given our interest

in systematic differences, we analysed log-transformed discount rates (averaged

across magnitude and delayÞ £ 2 ðtype of goodÞ £ 2 ðsalience of identity deficits)

ANOVAs, with SDI as a covariate. In this way, we controlled for the extent of

individuals’ identity deficits, isolating the impact of the experimental salience

manipulation. The central concern of this study is to demonstrate that the impact of

identity deficits made temporarily salient on discount rates results in a significant

interaction between type of good and identity deficit salience, but only for materialistic

individuals.8 As expected, this interaction was not significant for non-materialistic

individuals endorsement, Fð1; 18Þ ¼ 0:11; ns; h2 ¼ :01. In contrast, the predicted p

interaction between goods and salience condition was significant for materialistic

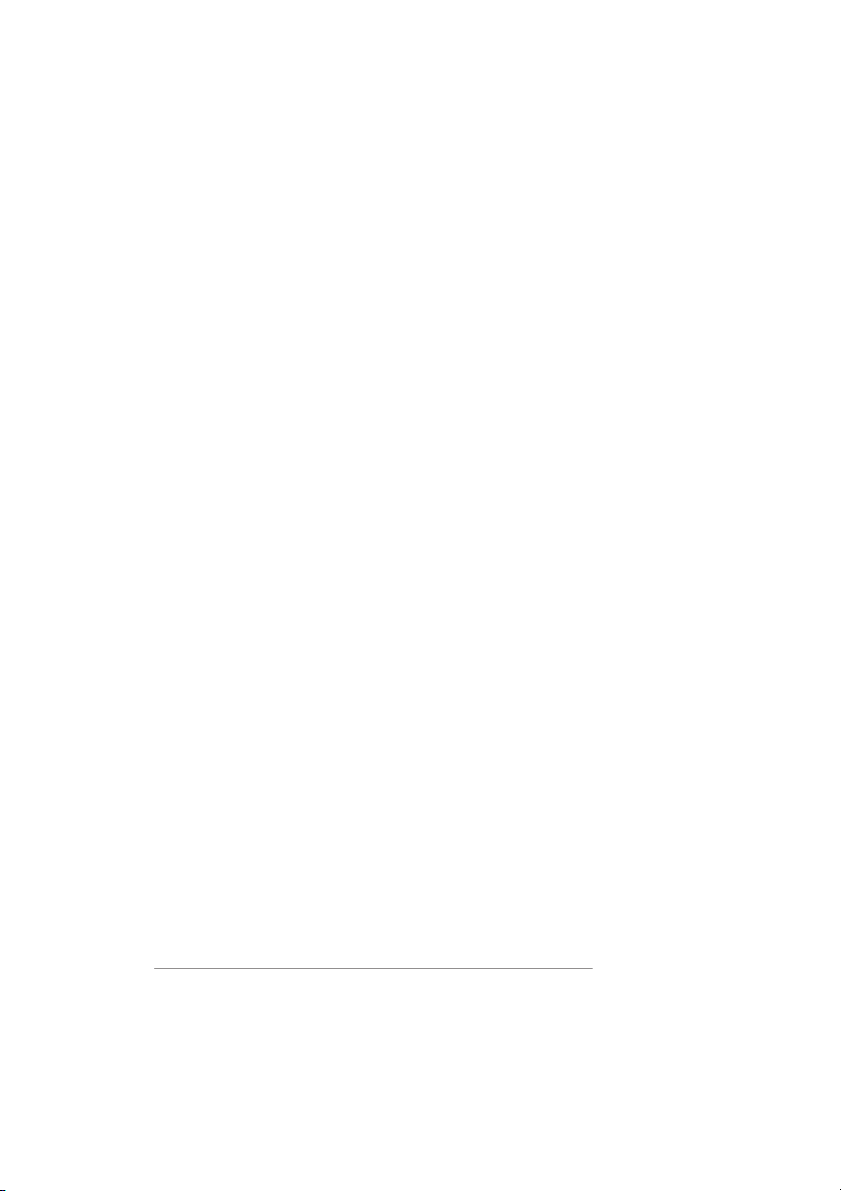

individuals, Fð1; 43Þ ¼ 4:77; p , :05; h2 ¼ :10, and mean daily discount rates are shown p in Figure 4.

The means show that discount rates for the identity-expressive good, clothes,

increase to some extent when materialistic consumers’ identity deficits are made salient,

compared to when they are not salient. Although we did not necessarily expect that

making identity deficits salient would impact on discount rates for the non-expressive

good, tools, it appears they are lower after identity deficits are made salient. In other

words, identity deficits salience appears to lead materialistic consumers to differentiate

more strongly between goods high and low in identity-expressive potential. Indeed, a

test for simple effects shows that, whereas the difference in discounting between

clothes and tools did not reach significance in the non-salient condition,

Fð1; 44Þ ¼ 1:27; ns, it was highly significant when identity deficits are salient,

Fð1; 44Þ ¼ 44:24; p , :001. Thus, making identity deficits temporarily salient seems

to make materialistic consumers more inclined towards impulsivity for identity-

expressive goods, such as clothes, that are relevant to their ideal self, in contrast to less expressive goods.

8 Main effects for salience condition were not significant, neither for materialists, Fð1; 43Þ ¼ 0:07; ns;h 2 ¼ :00, nor p

non-materialists, Fð1; 18Þ ¼ 0:90; ns;h 2 ¼ :05. p

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 770 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond 1.4 Tools Clothes 1.2 1 % s te 0.8 t ra n u isco d 0.6 ily a D 0.4 0.2 0 IDs not salient IDs salient

Figure 4. Materialistic individuals’ discount rates for identity-expressive versus non-expressive goods by identity deficits salience. Discussion of Study 3

The differential discounting of goods high and low in identity-expressive potential

appears a robust finding, given that it was replicated again in this third study using a

different sample of adult consumers. The predicted interaction between type of good

and identity deficits salience for materialistic individuals provides further support for

the model of consumer impulsivity proposed. When materialistic individuals focus on

their identity deficits, they demonstrate significantly greater impulsivity for a good likely

to help them express or improve their identity than for a non-expressive good.

Moreover, this effect was demonstrated after a rather mild manipulation of identity

deficits: respondents had merely listed aspects of themselves that they would like to

change directly before the discounting task. Clearly, there are much stronger cues for

materialistic individuals’ identity deficits to become temporarily salient, such as

comments from family or peers, stimuli present in the shopping environment, or

possibly through social comparison with ideal models in the media (Dittmar, 2008; Richins, 1995). CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The three experimental studies reported provide good evidence for the first prediction

derived from the proposed model of consumer impulsivity. They demonstrate the novel

finding that discount rates differ systematically between types of consumer goods:

people are less willing to delay immediate consumption of goods that offer high identity-

expressive potential. The present studies, by necessity, examined a limited range of

types of consumer goods. Clothes are a typical good used for the expression and

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Identity and consumers impulsivity 771

improvement of identity across different age and social groups, whereas sports gear is

likely to be more identity-expressive on average among younger respondents, such as

students. Basic body care products, such as shampoo or nail clippers, do not offer much

by the way of identity expression or repair for any social group, whereas the non-

expressiveness of tools could be gender-related, being more characteristic of women

than men. Finally, the low identity expressiveness of music items is likely to be age-

related, given that music items appear to play a much stronger role for identity among

young, and particularly adolescent, people (e.g., Dittmar, Barker, & Bond, 2009;

Rentfrow & Gosling, 2003) than in our sample of middle-aged consumers. Clearly, goods

can vary in identity-expressive potential among different groups of people, although

clothes and body care items seem to be generally regarded as high and low in identity-

expressive potential. Ideally, a range of different consumer goods would be examined in

a single experiment, but given the maximum number of discounting decisions each

respondent could sensibly be expected to make without undue fatigue meant that not

more than three goods could be examined in any one study. Thus, future research may

wish to identify additional goods particularly high and low in identity-expressive

potential not examined in the present research. Moreover, it is possible that the goods

we studied vary on dimensions other than identity-expressive potential, such as unit

cost or time course of consumption, and further research may wish to address explicitly

whether such dimensions have an additional impact on discounting, or interact in some

way with identity-expressive potential. Yet, notwithstanding the need to examine a

greater diversity of types of goods, as well as additional characteristics of goods, steeper

discounting for identity-expressive goods compared to non-expressive goods was

replicated in three studies, with different samples, and using somewhat different

combinations of goods. This convergence lends strength to the potential generalizability of this finding.

In addition to predicting that type of consumer goods is an identity-related factor

that impacts impulsivity, our new model of consumer impulsivity predicts that

materialistic individuals’ identity deficits should be systematically linked to greater

impulsivity, but only for goods that afford identity expression. This prediction was

supported in Study 2 with respect to individuals’ stable identity deficits and in Study 3

with respect to the temporary salience of identity deficits. These findings, taken

together, support the interpretation that identity-seeking constitutes a novel, hitherto

neglected, but significant dimension of temporal discounting, and therefore consumer

impulsivity. Thus, the individual difference factors in the proposed model that

increase impulsivity constitute psychological motives that can be interpreted as identity-

seeking. Endorsement of materialistic values can be seen as a commitment to identity

construction through the symbolic potential of material goods, and identity deficits

consist of gaps between individuals’ actual and ideal selves that they are motivated

to close. Thus, materialistic individuals are motivated to move closer to their ideal

self through making use of material goods with high identity-symbolic potential.

In terms of theoretical implications, the proposed model is innovative in providing

an account of, and empirical support for, specific individual difference factors that

increase consumer impulsivity, all of which are related to identity.

From the perspective of economic theory, the point could be made that materialistic

consumers derive utility from discounting clothes particularly steeply if, indeed, they

can close, or minimize their identity deficits successfully when they by this type of

consumer good on impulse (e.g., Borghans et al., 2008). However, there are theoretical

reasons why this is unlikely to be the case: the pursuit of identity-expressive goods can

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 772 Helga Dittmar and Rod Bond

raise confidence or competence momentarily, but is not suited to solving the more

essential and common reasons for identity deficits, such as a lack of close interpersonal

relationships, community belonging, or a sense of meaning in one’s life (Dittmar,

Banerjee, & Bond, 2009; Vignoles, in press). Moreover, we have shown empirically in

shopping diary studies that, although the perceived boost in identity-related benefits is

greater in more materialistic individuals directly after the impulse purchase, it has

dissipated by the time people get home with their purchase – in contrast to less

materialistic consumers (Dittmar, 2001, 2008).

With respect to applied implications, the finding in Study 3 that identity-expressive

goods are discounted more steeply when identity deficits are made salient to

materialistic individuals raises the question of how malleable the perception of one’s

identity deficits can be, and whether impulse buying might increase when individuals

are made to feel bad about certain aspects of themselves. On the one hand, this raises

worrying implications from a consumer point of view, where marketers could decide to

deliberately devise in-store stimuli aimed at increasing consumer identity deficits.

Indeed, some would argue that this is already the case (Kilbourne, 2006). On the other

hand, it also offers an evidence-based foundation for consumer education, where

individuals, especially less experienced consumers (such as adolescents), could be

alerted to this link between identity deficits and impulse buying. The idea that consumer

education, as part of the school curriculum, can help guard against uncontrolled buying

has already been piloted in a European Union project (Garce´s Prieto, 2002).

Two areas of future research on materialistic value endorsement and identity deficits

as predictors of consumer impulsivity deserve particular mention. The first would be an

extension to impulsive purchasing in actual retail environments. For example,

individuals’ endorsement of materialistic values could be assessed and their identity

deficits made salient before they enter a shop or store, and then their purchases of

identity-expressive goods could be used to assess the impact of this field experimental

manipulation.9 Second, a dimension of consumer impulsivity particularly worthy of

future research attention is the disregard for financial constraints and consequences.

The model proposed here could be extended from discount rates to studying the extent

and frequency of individuals’ impulse buying over time as an outcome of type of good,

materialistic value endorsement and identity deficits, which in turn may be an important

predictor of individual personal debt given alarming debt levels in the UK (Creditaction,

2006) and other developed countries, particularly in the current global climate of credit

crunch (Creditaction, 2009). Given the increasing drive towards consumerism (Dittmar,