Preview text:

Journal of Business Ethics

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04755-x ORIGINAL PAPER

Is Femvertising theNew Greenwashing? Examining Corporate

Commitment toGender Equality

YvetteSterbenk1· SaraChamplin2· KaseyWindels3· SummerShelton4

Received: 6 November 2019 / Accepted: 20 January 2021

© The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature B.V. part of Springer Nature 2021 Abstract

This study examined the potential for a new area of corporate social responsibility (CSR) washing: gender equality. Com-

panies are increasingly recognized for advertisements promoting gender equality, termed “femvertisements.” However, it

is unclear whether companies that win femvertising awards actually support women with an institutionalized approach to

gender equality. A quantitative content analysis was performed assessing company leadership team listings, annual reports,

CSR reports, and CSR websites of 61 US-based companies (31 award winners and 30 non-winning competitors) to com-

pare the prevalence of internal and external gender-equality CSR activities of companies that have (versus have not) won

femvertising awards. When controlling for number of employees and annual revenue, award-winning companies committed

to more internal efforts that support women than non-award-winning companies. However, no significant differences were

found in the number of external efforts or representation in female leadership between companies with and without award-

winning femvertisements. Overall, a majority of award-winning companies (81%) engaged in less than ten of the possible

23 gender-equality CSR activities, suggesting these companies’ female empowerment commercials were often not in line

with their broader CSR activities. While more research is needed in this area, we propose the term “fempower-washing” to

describe CSR-washing in the context of gender equality.

Keywords Femvertising· Corporate social responsibility· CSR advertising· Corporate hypocrisy· CSR-washing

An emerging area of corporate social responsibility (CSR)

As socially conscious consumers, employees, and inves-

is activism, wherein companies take stances on some-

tors increasingly pressure companies to address social

times controversial social issues such as LGBTQ+ rights, issues (Castaldo etal. ;

2009 Cone Communications 2015;

race relations, or gender equality (Chatterji and Toffel Dodd and Supa ; 2014 Edelman ; 2017 Varghese and Kumar

2016; Dodd and Supa 2014; Madrigal and Boush 2008).

2020a), many firms respond by attempting to tackle these

complicated topics through CSR advertising (Pomering etal.

2013). Short videos, 30-second commercials, or experiential

brand activations allow companies to reach large audiences * Yvette Sterbenk ysterbenk@ithaca.edu

with simple, feel-good messages that connect their brands Sara Champlin

to social causes in positive ways (Browning etal. 2018). sara.champlin@unt.edu

However, stakeholders often question whether companies Kasey Windels

engaged in and recognized for their pro-social advertising kwindels@ufl.edu

concurrently back their messages with corporate actions Summer Shelton (Wired staff ; 2018 Jones ) 2019 . shelsumm@isu.edu

Companies whose pro-social advertisements are incon-

sistent with their corporate actions are engaging in CSR-

washing, defined by Pope and Waeraas ( ) 2015 as “the suc- 1

Roy H. Park School ofCommunications, Ithaca College, Ithaca, NY, USA

cessful use of a false CSR claim to improve a company’s 2

Mayborn School ofJournalism, The University ofNorth

competitive standing” (p. 175). The practice of CSR-wash- Texas, Denton, TX, USA

ing is risky. If discovered, it can have a negative impact 3

University ofFlorida, Gainesville, FL, USA

on corporate reputation and stakeholder trust (Wagner etal. 4

Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID, USA 1 3 Vol.:(0123456789) Y.Sterbenk et al.

2009; Kim etal. 2015; Yoon etal. ) 2006 . Thus, it is impor-

In the sections that follow, we outline the relevant litera-

tant that companies support their advertising with measur-

ture on CSR advertising, femvertising, and CSR-washing.

able internal and external corporate actions that are clearly

We then delineate research questions regarding CSR-wash-

communicated through other corporate channels.

ing in the context of gender equality initiatives and describe

The concept of CSR-washing has been commonly

the process and results from this research. Implications for

applied to environmental practices (Delmas and Burbano

research and practice are then discussed.

2011; Nyilasy etal. 2014; Siano etal. 2017), also known

as “greenwashing.” Limited research also exists regarding

CSR-washing of other social issues, such as LGBTQ+ sup- Literature Review

port and racial inequities (Mitchell and Ward ; 2010 Sobande

2019). With the tremendous growth in brand activism and

The Importance ofBacking CSR Advertising

the promotion of social justice in corporate advertising withAction (Pomering etal. )

2013 , it is critical that researchers examine

the emergence of CSR-washing in other domains, beyond

CSR advertising and other communications that address environmental contexts.

socio-political issues outside of a company’s core business

This study explores CSR-washing as it relates to compa-

focus are increasing (Dodd and Supa ; 2014 Chatterji and

nies promoting gender equality through “femvertisements,”

Toffel 2016; Pomering etal. )

2013 . With increased pressure

or advertisements that communicate about issues related to

for corporations to speak out on social issues (Castaldo etal.

female empowerment (Zeisler 2016). Gender equality is an

2009; Cone Communications 2015; Dodd and Supa 2014;

issue consumers want brands to support (Cone Communica-

Edelman 2017; Varghese and Kumar 2020a), CSR advertis-

tions 2017) and, since 2015, several industry organizations

ing is often the easiest way to educate (or convince) consum-

have created categories to recognize femvertisments in their

ers about a firm’s socially responsible activities or view-

award programs. Femvertising awards, and the popular fem-

points, as it creates a positive association between a specific

vertisements themselves, are shared broadly on social media, cause and the company (Sheikh and Beise-Zee ) 2011 .

resulting in women positively associating these award-win-

Consumers’ perceptions of CSR-focused advertising are

ning brands with female empowerment (Think with Google

formed in the context of their understanding of the com- 2017; Abitbol and Sternadori ) 2019 . However, a number of

pany’s reputation and social commitment, as well as their

companies that have won prestigious femvertising awards

understanding of the social issue itself (Pomering etal.

have simultaneously received negative media coverage for

2013; Skard and Thorbjornsen 2014; Yoon etal. 2006).

lack of female representation at the leadership level (Stor-

Recent research suggests that a majority of consumers,

beck 2017), allegations of sexism (Hsu ) 2018b , and, in the

especially young adults, will engage in information seeking

case of some conglomerates, conflicting messages about

to evaluate the authenticity of a company’s CSR advertis-

body image in ads for other products (Blay ) 2016 . Ulti-

ing and other initiatives (Cone Communications ) 2017 . It

mately, this calls into question whether femvertising is sim-

is important that companies be aware of this, as consum-

ply a newly-emerged form of CSR-washing.

ers may use large-scale communication platforms, such as

This study adds a new perspective to recent literature that

social media, to challenge corporate motives behind CSR

examines consumer responses to femvertising and the ways advertising.

in which gender empowerment is framed in advertisements

A company’s advertising messages also impact employ- (Abitbol and Sternadori ;

2019 Feng etal. 2019; Sobande

ees’ opinions of the brand, wherein employees’ positive con-

2019; Windels etal. 2020). We draw upon CSR-washing

nection with the brand increases when the company’s CSR

and corporate hypocrisy literature (Pope and Waerass 2015;

advertising is backed by similar internal communications Wagner etal. )

2009 to examine whether companies have

(Hughes 2013; Donia and Tetrault Sirsly ) 2016 . Employees’

invested in internal and external CSR work other than the

perceptions of a company’s CSR commitment are important

feel-good messages of their award-winning ads. Beyond

because industry research shows that the Millennial gen-

greenwashing, few studies have explored other forms

eration (currently the largest generation in the workforce)

of CSR-washing and no studies have examined the issue

evaluates and prioritizes CSR commitment when making

of female empowerment and femvertising as it relates to

job decisions (Cone Communications ) 2016 .

CSR-washing, despite this being a rapidly growing area of

CSR advertising is considered “promotional CSR,” which

research and practice. By extending CSR-washing to the

is often more easily understood by stakeholders than “insti-

previously unexamined area of female empowerment, this

tutionalized CSR.” Institutionalized CSR is a comprehen-

paper provides a new category against which to compare

sive program that integrates socially responsible actions

greenwashing and other types of CSR messaging.

into the operations across a company (Pirsch etal. 2007),

touching multiple areas such as employee training, hiring 1 3

Is Femvertising theNew Greenwashing? Examining Corporate Commitment toGender Equality

practices, supply chain commitments, and NGO partner-

(Glass: The Lion for Change, n.d.). Companies and agen-

ships. However, consumers are suspicious of promotional

cies that win awards for their femvertisements proac-

CSR and of advertising, both of which they perceive as self-

tively submit their work for consideration, implying pride serving (Pomering and Johnson ;

2009 Webb and Mohr 1998; and confidence in the message they are associating with Obermiller and Spangenberg ;

1998 Obermiller etal. 2005).

their brand. Further, the industry professionals judging

In comparison, institutionalized CSR is more effective at

these competitions award companies as leaders in female

improving loyalty and decreasing consumer skepticism empowerment.

(Pirsch etal. 2007). Thus, a company’s promotional CSR

Reception ofFemvertising

efforts will be most successful if supported by institution-

alized CSR actions. In the case of this study, we explore

There is considerable literature showing that advertising

whether companies recognized for their female empower-

continues to incorporate gender stereotypes, though the use

ment advertisements (promotional CSR) are supporting

has decreased over time (Eisend ; 2010 Wolin ) 2003 . Emerg-

those messages with a comprehensive set of actions such

ing research suggests that femvertisements resonate with

as measurable quotas, increased training and promotional

women because advertisements with female empowerment

opportunities for female employees, and support for external

messages can actually counter these historical and existing

causes that support gender equality (institutionalized CSR).

gender stereotypes and create positive self-views for women Femvertising

(Abitbol and Sternadori 2019; Varghese and Kumar 2020a). Varghese and Kumar ( )

2020b argue that the increasing prev-

The Rise ofFemvertising

alence of femvertising can be attributed, in part, to women’s

demand for more accurate representation, especially regard-

The success of Dove’s 2004 Campaign for Real Beauty

ing gender roles and stereotyping. Indeed, empirical research

inspired tremendous growth in advertisements that address

supports this supposition, wherein traditional depictions of women’s issues (Bahadur )

2014 . Additionally, the #MeToo

women—as hypersexualized and with “perfect” or “flaw-

movement increased the number of women working in

less” bodies—elicited greater psychological reactance when

advertising and marketing agency leadership roles. This

compared to femvertisements, thus decreasing attitudes

furthered the charge for improved representations of women

toward the brand and advertisement (Akestam etal. ) 2017 .

in advertising and acknowledgement of female consumers’

In a study conducted by SHE Media, 52% of women indi-

spending power (Hsu 2018a; Wojcicki ; 2016 Varghese and

cated that they purchased a product because they liked how

Kumar 2020b). Brands that engage in female empower-

the company’s advertisements depicted women. Nearly half

ment campaigns are often rewarded with commercial suc-

said that the purchase made them feel good about support- cess (Becker-Olsen etal. )

2006 . Data show that a majority

ing the brand. A majority of the women also believed that

of Americans (84%) support companies taking a stand for

femvertisements dismantled gender barriers (Castillo 2014).

women’s rights (Cone Communications 2017), and many

While female consumers exhibit generally positive responses

women feel that gender equality is a human rights issue

to femvertisements, it is unclear how aware consumers are

(Castillo 2014). In response, companies from L’Oreal to

of corporate practices when viewing these advertisements.

Ram Trucks now address women’s issues and experiences

For example, Abitbol and Stenadori ( ) 2019 found that con-

in their advertising by producing femvertisements: advertis-

sumers’ responses to the femvertisements of Google and

ing and marketing campaigns that focus on women’s issues,

Microsoft were positive, even though the companies were

celebrate women, and seek to reduce gender stereotypes

experiencing public lawsuits about harassment and discrimi-

(Zeisler 2016). One example of this is a commercial from

nation at the time of the research.

Bud Light, which shows two celebrities (Amy Schumer and

Other companies that create femvertisements, however,

Seth Rogan) drinking beer at a bar, discussing the concept

have experienced increased scrutiny of their own gender- of equal pay.

equality practices. For instance, State Street Global Advi-

In 2014, SHE Media coined the term “femvertising”

sors, as a result of its “Fearless Girl” campaign featuring

at Advertising Week to describe the growing number of

a sculpture of a young girl boldly confronting the bull in

ads that address issues of gender equality, specifically

the Wall Street area of New York City, attracted media

women’s empowerment (Femvertising, n.d.). Since 2015,

attention for its own pay inequities, facing such headlines

SHE Media has recognized companies with Femvertis-

as “Bank behind Fearless Girl Statue Settles Gender Pay

ing Awards for “challenging gender norms” (Femvertising Dispute” (Holman )

2017 . While femvertising is a grow-

Awards, n.d.), and Cannes has awarded Glass Lions to

ing phenomenon in industry practice, research has not yet

advertising that “demonstrates ideas intended to change

examined the extent to which companies that tout female

the world; work which sets out to positively impact

empowerment through promotional CSR support the social

ingrained gender inequality, imbalance or injustice” issue institutionally. 1 3 Y.Sterbenk et al. CSR‑Washing

“woke-washing” is used to describe brands that take on

social issues in their marketing with little action behind

Research shows that stakeholders, especially consumers their messages.

and employees, expect a company to show authentic and

CSR-washing can harm companies that do not support

long-term commitment to the causes it supports (Madrigal

their socially responsible advertising with comparable and Boush ; 2008 Dawkins ; 2004 Hughes ; 2013 Donia and

internal and external corporate initiatives (Wagner etal.

Tetrault Sirsly 2016). Positive associations result when

2009; Kim etal. 2015; Yoon etal. ) 2006 . However, some

consumers and employees feel a company’s motives are

research suggests companies that engage in CSR-washing

sincere. Neutral or negative associations result when

through advertising actually enjoy the same financial and

motives are unclear or insincere, or when CSR messag-

reputational benefits as those that are authentic in their

ing and actions are inconsistent with each other (Wagner

CSR efforts, because consumers take CSR ad messages at etal. 2009; Dawkins ; 2004 Yoon etal. ; 2006 Donia and face value (Pope and Wareass ; 2015 Abitbol and Sternadori

Tetrault Sirsly 2016). Wagner and colleagues (2009) apply

2019). Some scholars (Wagner etal. ) 2009 even suggest

the term “corporate hypocrisy” when company statements

that companies should make their CSR statements more

are inconsistent with observed behaviors, and Pope and

abstract, because failure to live up to company statements

Wareass (2015) define this deliberate use of false claims can be damaging.

to improve competitive standing as “CSR-washing.”

Literature on CSR-washing, greenwashing, and corpo-

The best-known form of CSR-washing is greenwashing,

rate hypocrisy provides helpful definitions and frameworks

which is characterized by decoupling behavior: making

that can be applied to companies engaging in femvertising.

positive statements or distributing advertisements about a

Though the effects of greenwashing are well-documented,

company’s environmental responsibility in an attempt to

there exists limited research on other forms of CSR-washing

satisfy stakeholders. Greenwashing occurs when advertis-

and none related to gender-equality issues. The present study

ing claims are not supported with operational practices and

makes an important contribution to this literature.

thus mislead consumers about a company’s environmental practices (Delmas and Burbano ; 2011 Nyilasy etal. 2014; Research Questions Siano etal. ; 2017 Walker and Wan ) 2012 . Walker and Wan ( )

2012 analyzed company websites and CSR reports

Existing literature on femvertising has primarily focused on

to measure companies’ substantive environmental actions

consumer response to the advertisements themselves (Feng

(“green walk”) versus symbolic environmental actions

etal. 2019) or the framing of the messages (Sobande 2019;

(“green talk”). Overall, the presence of more symbolic Champlin etal. )

2019 . However, no research to date has

actions (or “talk”) had a negative financial impact on the

explored whether companies that engage in femvertising

company. Walker and Wan suggest “that organizations

have committed to the cause in their overall CSR program,

are only able to deal with certain areas at a time. Indeed,

a factor that can impact long-term reputation and loyalty

it would be extremely difficult for a single firm to per- (Pirsch etal. )

2007 . As noted, companies that win femvertis-

form well in all environmental categories that we iden-

ing awards proactively submit their work for consideration,

tified, and no firm in our sample was able to do so” (p.

implying confidence in the association of their brand with

237). It is important to note that not all greenwashing is

female empowerment. Those companies are then recognized

based on outright “lies’’ about a company’s actions. Most

as leaders in female empowerment messaging by industry

greenwashed ads instead feature vague statements or use

professionals, and their ads are shared widely on social

imagery and colors that positively associate a brand with

media by consumers. Given that today’s consumers want

good environmental behavior (Kangun etal. 1991; Parguel

companies to take a stand on social issues and will scrutinize etal. ) 2015 .

the authenticity of these initiatives (Cone Communications

While greenwashing is the most common and most

2017), it is possible that companies recognized for their

researched form of CSR-washing, there are other forms

female empowerment advertising messages also support

such as rainbow-washing, in which organizations use

gender equality in meaningful ways. Still, this research is

rainbow patterns and symbols to appear aligned with the

in its infancy and no work has previously examined CSR-

LGBTQ + community (Mitchell and Ward ) 2010 . Pink-

washing of female empowerment. Thus, this study sought

washing, a term used to describe companies that borrow to explore the following:

breast cancer imagery and symbols to appear aligned

with support of breast cancer awareness efforts, often

RQ1 Are femvertising award-winning companies more

without meaningful support is another form of CSR-

likely than non-award-winning companies to commit to (a) washing (Carter )

2015 . Additionally, in academic and

internal and (b) external efforts that support women? popular literature (Sobande ; 2019 Mahdawi 2018) the term 1 3

Is Femvertising theNew Greenwashing? Examining Corporate Commitment toGender Equality

Members of the ad industry have called for companies

messages watched by women on YouTube (2016–2017),

to go beyond female empowerment messaging and hire

and advertisements from three lists curated by Ads of the

women on their boards (Diaz and Zmuda 2014). Not only

World: (4) Girl Power in Advertising, (5) Gender Equality

does representation at the leadership level signify a corpo-

in Advertising (2013–2017), and (6) International Women’s

rate commitment to empowering and recognizing the value

Day (2018–2020). Two hundred and fifty-seven femvertise-

of female employees, research suggests it may also correlate

ments were identified, including print, video, experiential,

to a higher level of overall corporate responsibility activity

and other platforms. To maintain consistency in material

(Cook and Glass 2018; Setó‐Pamies ; 2015 Macaulay etal.

type, we focused on companies that won awards for video

2018), as well as to a higher number of female employees

and experiential campaigns. Additionally, these types of

in a company (Modiba and Ngwakwe ; 2017 Skaggs etal.

advertisements were selected as they were more likely to

2012). As a result, we pose the following question: have been shared broadly.

Since regulations about gender-equality requirements

RQ2 Do femvertising award-winning companies and non-

for companies vary from country to country, we excluded

award-winning companies differ in their female representa-

brands whose parent companies are not currently headquar-

tion in the leadership of their company including the (a)

tered in the United States. One company (P&G) represented

percent of women on the board and (b) percent of women in

multiple brands recognized for their individual femvertise- leadership positions?

ments. Companies were removed from the list if they did

not have enough materials to adequately review CSR and

There are numerous internal and external CSR activities

leadership activities. The resulting list consisted of a total

in which companies might choose to engage to show their

of 31 femvertising award-winning companies from 2015 to

support for gender equality, including employee resource 2019 (n = 31).

groups, hiring commitments, and company-wide trainings

The researchers then developed a comparative list of US-

(internal), as well as partnerships with non-profits, help-

based competitors of the award-winning companies that had

ing members of a community, connecting with consumers

not received awards for video or experiential femvertise-

and others (external). To further understand the extent to

ments. Using Owler.com, we identified the top competi-

which CSR-washing occurs in this context, it is also impor-

tive US-based company in the same industry that offered a

tant to examine the types of activities supported most and

similar product/service focus, was closest to the size of the

least often by these companies. These findings will shed

award-winning company, and, finally, which offered enough

light on the areas of opportunity that companies, especially

material for review. Some of the companies had the same

those with award-winning femvertisements, might consider

competitors, thus the final list consisted of 30 unique compa-

engaging in further to justify their public displays of gender nies (

n = 30). While some of the companies on the compara- equality.

tive list may have had female empowerment advertisements,

they were not award-winning and thus had not received the

RQ3 Which types of gender-equality CSR activities are

recognition and press for their efforts in this area. The final

engaged in most often and least often by femvertising award

list of all 61 US-based companies (N = 61) can be found in winners and non-award winners?

Table1. This sample size provided sufficient data to address

the research questions proposed and exceeds that utilized

in similar research (e.g., de Jong and van der Meer 2015, Method

(N = 6); Fischer 2020, (N = 7)). Compiling Data Profiles Materials Selection

Companies typically communicate their CSR activities

Generating Company Lists

through annual reports, CSR reports, and websites, and these

sources are the most widely used for analyzing and profiling

Two lists of companies were developed for the present study; CSR actions (Arvidsson ; 2010 Begum ; 2018 de Jong and

one consisted of companies that had received an award van Der Meer ; 2015 Waller and Lanis ; 2009 Walker and

for their femvertising and another list consisted of simi- Wan 2012). In fact, Zerbini ( )

2017 notes that CSR reports in

lar, competitor companies that had not received an award

particular provide insight into corporate priorities because

for female empowerment advertising. We first compiled a

they are voluntary disclosures, and “the disclosure of private

master list of award-winning femvertisements including

information” helps us to “embrace the implications linked

(1) ads that won #Femvertising Awards from SHE Media

to the motivations that led the sender to reveal such infor-

(2015–2019), (2) the Cannes’s Glass Lion for Change

mation” (p. 9). We compiled these materials from the most

(2015–2018), (3) the most viral ads with empowering

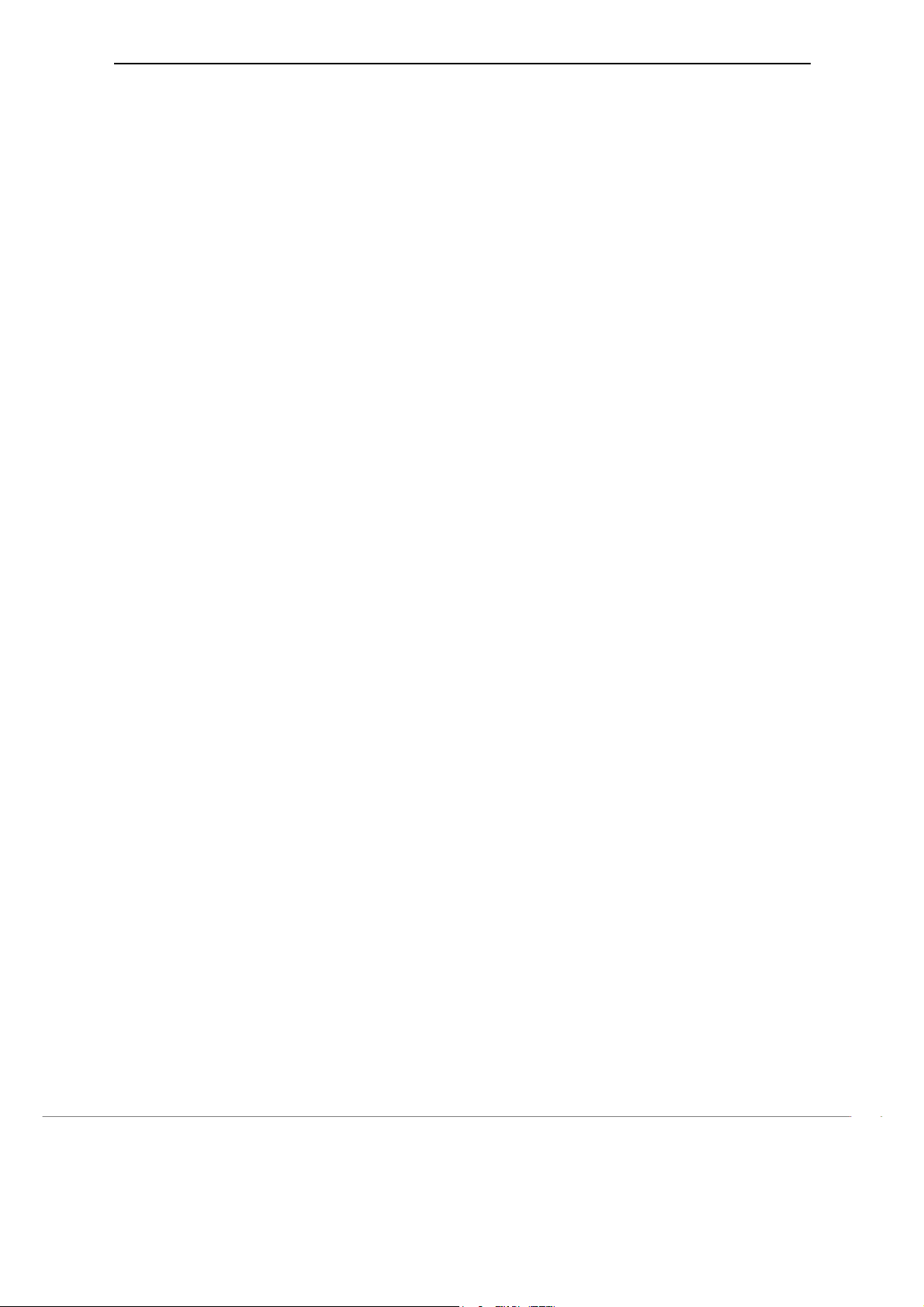

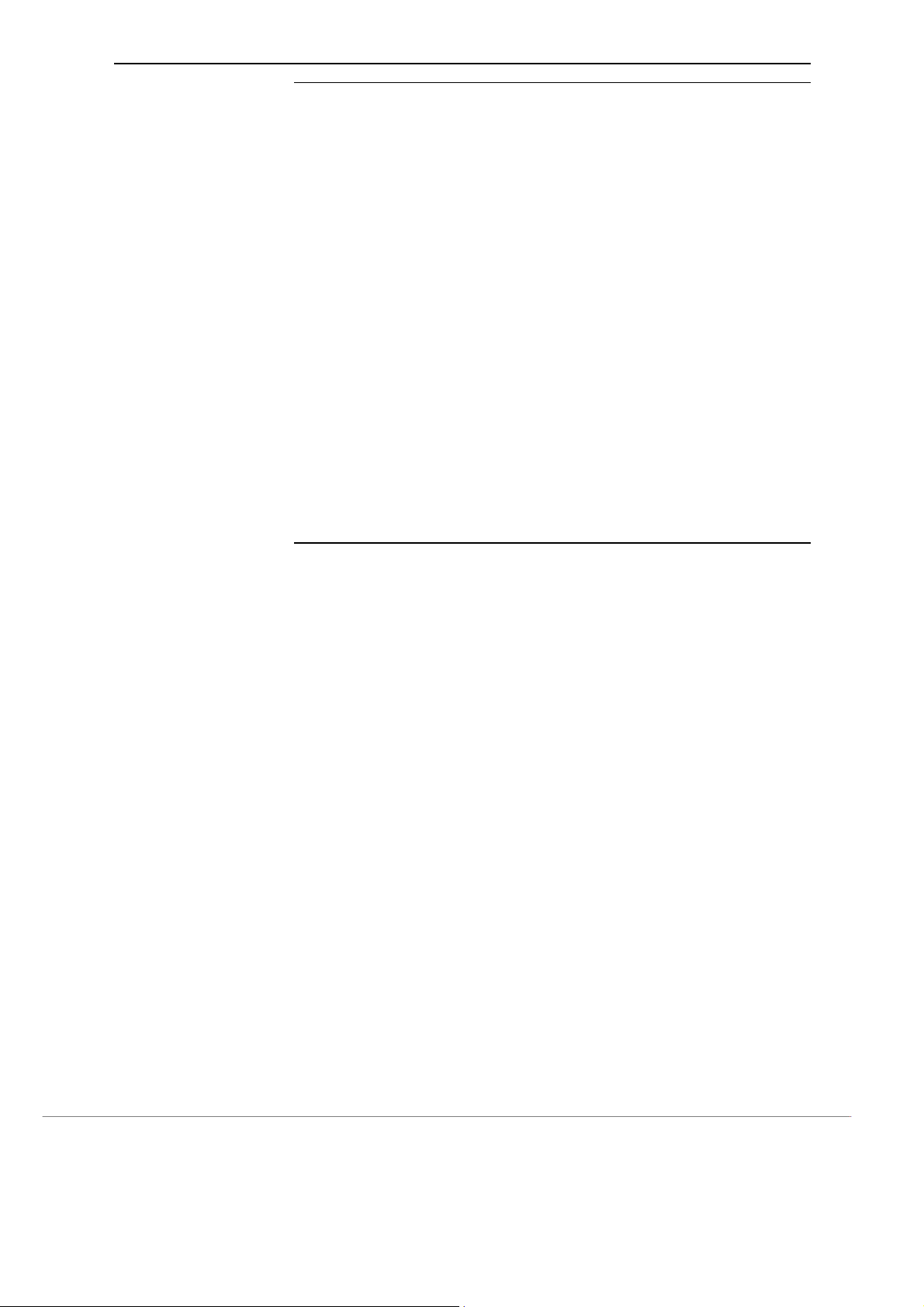

recent year that were available for each company. Because 1 3 Y.Sterbenk et al. Table 1 Companies and

industries Award-Winning Companies

Non-Award-Winning Companies Anheiser Busch (Beverage) AT&T (Telecommunications) Apple (Technology) BlackRock (Financial)

Ascena Retail (Clothing Retail)

The Boston Beer Company (Beverage) Coca-Cola Company (Beverage)

Campbells (Consumer Packaged Goods) Coty (Beauty)

Colgate Palmolive (Consumer Packaged Goods)

Dick’s Sporting Goods (Retail)

Columbia Sportswear (Clothing Retail) Facebook (Technology) Comcast (Media)

General Mills (Consumer Packaged Goods) Dell (Technology)

Georgia Pacific (Consumer Packaged Goods) Ford Motor Company (Auto) GM (Auto) Google (Technology)

Hormel (Consumer Packaged Goods) Harley Davidson (Auto)

Kimberly-Clark (Consumer Packaged Goods) Hasbro (Toy)

Levi Strauss & Co (Clothing Retail)

Hershey (Consumer Packaged Goods) Mattel Inc. (Toy)

International Paper (Consumer Packaged Goods) McDonalds (Restaurant) Johnson & Johnson (Beauty) Microsoft (Software)

Kellogg Company (Consumer Packaged Goods)

Mondelez (Consumer Packaged Goods) Keurig Dr. Pepper (Beverage) Nike (Clothing Retail)

Kraft Heinz (Consumer Packaged Goods)

P&G (Consumer Packaged Goods) L.L. Bean (Clothing Retail)

Pepsico/Frito Lay (Consumer Packaged Goods) MoneyGram (Financial) Polaris (Auto) New Balance (Clothing Retail) REI (Clothing Retail) Oracle (Software)

SC Johnson (Consumer Packaged Goods) PVH (Clothing Retail)

State Street Global Advisors (Financial) Revlon (Beauty) T-Mobile (Telecommunications) Sprint (Telecommunications) UnderArmour (Clothing Retail)

Tivity Health/Nutrisystem (Health) Verizon (Telecommunications) TJX (Clothing Retail) VF (Clothing Retail)

Tyson (Consumer Packaged Goods) Walt Disney Company (Media) Walmart (Retail) Weight Watchers (Health) Yum Brands (Restaurant) Western Union (Financial)

some research suggests that firm size may correlate with

team, we first went to the company’s website looking for

increased philanthropic activity (Brammer and Millington

self-reported information in the “About Us/Leadership” sec-

2006; Udayasankar 2008), we also solicited the company’s

tions. For the rare companies where this information was

current number of employees and annual revenue, using

not available, we used the public data source Bloomberg Gale Business Insights. (Holder-Webb etal. ) 2009 .

A coding guide was compiled that offered a comprehen-

Coding Schema andAnalysis

sive list of the kinds of corporate activities that companies

may engage in to address issues of gender equality and

Six researchers examined the collected materials and created

female empowerment. The list of activities can be found in

profiles for each company, compiling stated CSR activities

Table2. One researcher developed profiles for a sample of

that related to gender equality and women’s empowerment

10 companies in similar industries and of similar sizes to

(Waller and Lanis 2009; Leech and Onwuegbuzie ; 2008 de

some of the companies in the final dataset. These 10 profiles Jong and van der Meer )

2015 . de Jong and van der Meer

were used to train coders and acquaint them with the coding

(2015) used the following criteria to build CSR profiles for

guide. Four researchers reviewed the training profiles, dis-

analysis: “the activity must be performed voluntarily; the

cussed their findings, and then met to update and clarify the

activity must not be obligated by law; the activity must be

coding guide. The researchers carried out multiple rounds

concrete (the text made clear what the activity involved)”

of training, coding, and discussion. Following the coding

(p. 76). We used these same criteria, with the addition that

training, two rounds of coding were performed to improve

the activity addressed women’s empowerment in some way.

reliability scores. Two of the researchers coded 40% (n = 20)

Each company profile was created and edited by at least two

of the test sample data to establish reliability. A majority

different coders to ensure accuracy of the compilation. Also,

of the Krippendorff’s Alpha reliability values ranged from

one researcher compiled the number of women on each com-

0.70 (external: scholarships) to 1.00. Three categories had

pany’s board (when applicable) and in senior leadership, as

low reliability values, ranging from 0.61 (external: programs

well as the total revenue of each company. Because compa-

for women) to 0.63 (internal: internal events). Further, two

nies differ in how they define who sits on a senior leadership

of the external efforts (product lines and conversing with 1 3

Is Femvertising theNew Greenwashing? Examining Corporate Commitment toGender Equality

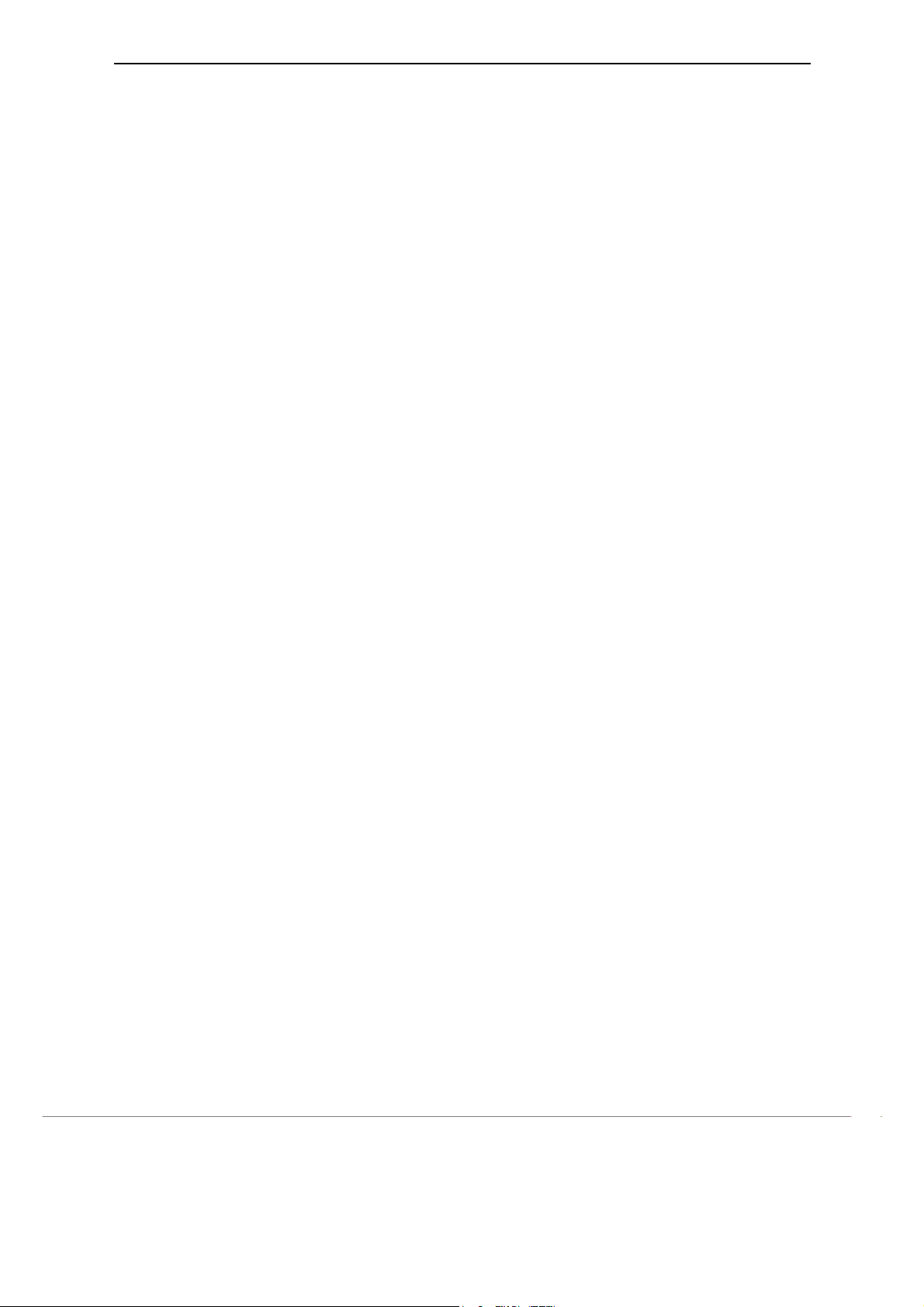

Table 2 CSR activities in coding guide Diversity reporting

Does the organization publish the numbers of women in the organization in a diversity report, in its CSR report, or on its website? Internal Programs + Actions

Building an internal talent pipeline for women leaders

•Women in leadership pipeline initiatives—i.e., specific training or mentoring programs

•Measurable goals to increase female representation on board or at leadership/management level

•Measurable goals to increase female representation at lower levels of the company

•Programs focused on recruiting female workers, specifically

•Internal events focused on gender issues and empowerment

Benefits and Human Resource Support

•HR Benefits + Policy changes aimed at gender equality

•Signing a public commitment to gender equality inside the company

•Pay equality initiatives or commitments

•The company states or changes their policy on hiring process

Employee Engagement in Ensuring Gender Equality

•Employee Resource Groups (ERGs), affinity groups, mentoring or networking Groups for female employees

•A committee, employee, or department formally coordinating gender diversity and inclusion for the company Operations

•Initiatives to work with other businesses, suppliers and partners that are gender- inclusive

•Sourcing from Women-Owned Businesses

•Support programs for women in the supply chain Training

•Gender bias training that goes beyond sexual harassment training External Programs + Actions Cause-Related Marketing

•Support for non-profit women’s organizations, NGOs, or non-profits that focus on gender or women’s issues

•Company scholarships and grants program (given directly to women)

•Company programs that benefit women in the community

•Company programs that benefit girls in the community Marketing communications

•Producing advertising and marketing campaigns that celebrate women or work to reduce gender stereotypes (beyond the current femvertise- ment) Product

•Diversifying or rethinking product lines aimed at expanding gender reach or addressing gender stereotypes (i.e., dual gender clothing)

•Conversing with female consumers to meet their needs, specifically Industry

•Initiatives that encourage their industry or help other businesses to address gender equality

female consumers) had very low reliability values (0.46 and Results

0, respectively), but this can be attributed to the smaller sam-

ple size. For example, conversing with female consumers

Research Questions 1 and2

had a Krippendorf’s Alpha value of 0; however, the percent

agreement was 95%, indicating only one disagreement in the

The first research question asked whether femvertising

dataset. Given that the percent agreement was still extremely

award-winning companies were more likely to commit to

high among coders (80–95% in these cases), these categories (a) internal and (b) external efforts that support women. It

were retained for analysis. Once agreement was reached,

was also important to determine whether certain aspects of a

one coder coded the remaining companies identified in the

company might influence its engagement in gender-equality final dataset.

initiatives, as this might begin to explain differences in the

types of companies that are more or less likely to engage in

efforts toward gender equality. As such, the second research 1 3 Y.Sterbenk et al.

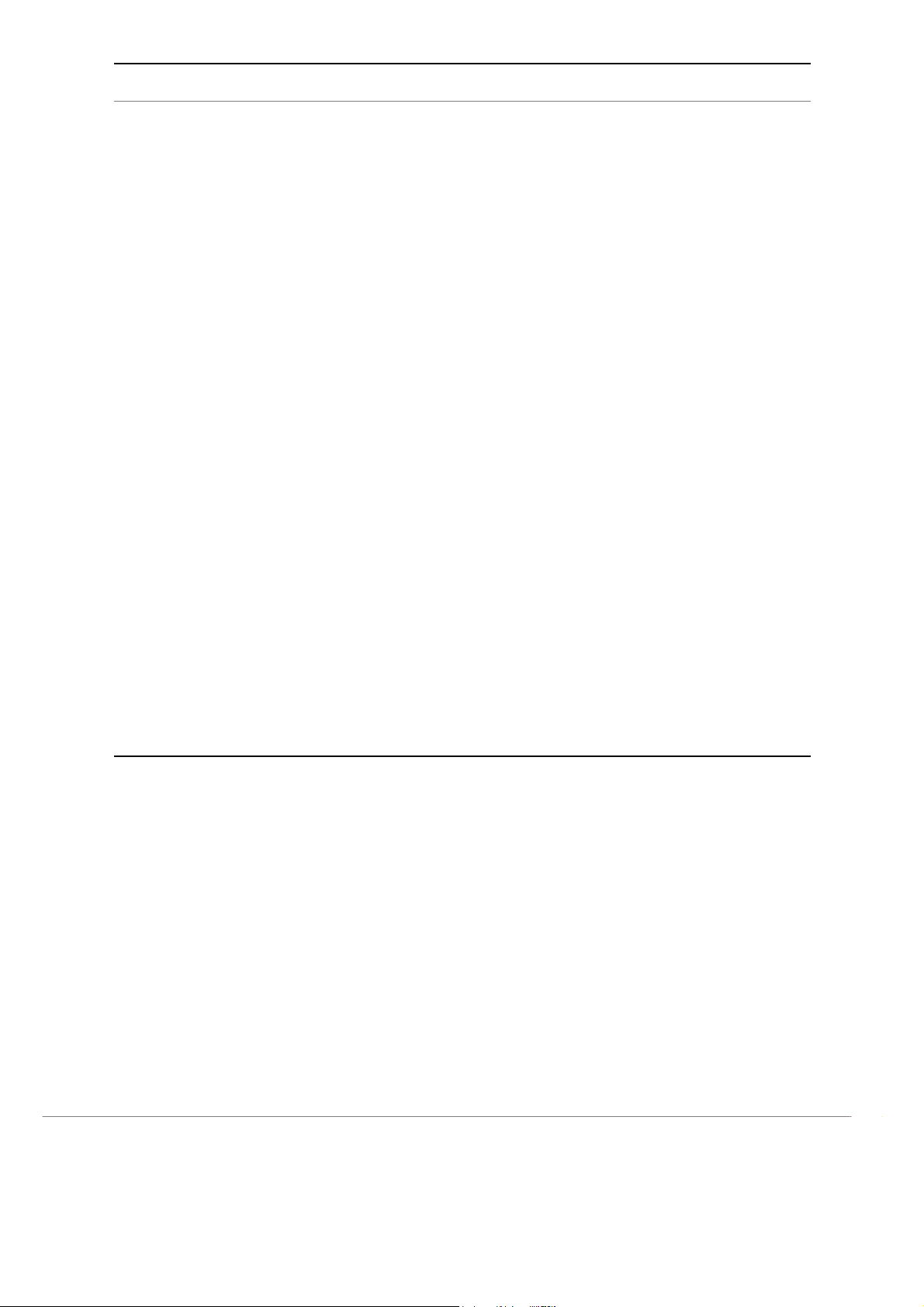

Table 3 Percentage of women Company Received award Percent of women on Percent of women in

on the board and percentage of the board leadership positions women in leadership positions (%) (%) Anheiser Busch Yes 33 6 Apple Yes 29 25 Ascena Retail Yes 58 57 AT&T No 25 20 BlackRock No 22 16 Boston Beer Company No 29 25 Campbells No 36 20 Coca-Cola Company Yes 31 30 Colgate Palmolive No 40 40 Columbia Sportswear No 36 21 Comcast No 30 33 Coty Yes 22 30 Dell No – 10 Dicks Sporting Goods Yes 20 23 Facebook Yes 33 28 Ford Motor Company No 21 18 General Mills Yes 46 25 Georgia Pacific Yes – 31 GM Yes 55 19 Google No 27 0 Harley Davidson No 20 25 Hasbro No 38 13 Hershey No 42 25 Hormel Ye s 22 17 International Paper No 27 20 Johnson & Johnson No 30 27 Kellogg Company No 42 42 Keurig Dr. Pepper No 25 17 Kimberly-Clark Yes 36 20 Kraft Heinz No 9 30 Levi Strauss & Co Ye s 27 44 L.L. Bean No – 0 Mattel Yes 30 14 McDonalds Yes 23 42 Microsoft Ye s 22 20 Mondelez Yes 23 9 MoneyGram No 11 29 New Balance No – – Nike Yes 21 20 Oracle No 27 33 P&G Yes 36 41 Pepsico/Frito Lay Yes 23 26 Polaris Ye s 30 7 PVH No 36 25 REI Yes 42 44 Revlon No 42 69 SC Johnson Ye s 43 – Sprint No 10 25 State Street Global Advisors Yes 25 25 1 3

Is Femvertising theNew Greenwashing? Examining Corporate Commitment toGender Equality

Table 3 (continued) Company Received award Percent of women on Percent of women in the board leadership positions (%) (%) T-Mobile Yes 27 33 Tivity Health/Nutrisystem No 45 17 TJX No 8 18 Tyson No 25 31 UnderArmour Yes 20 13 Verizon Ye s 30 31 VF Yes 30 20 Walmart No 36 21 Walt Disney Company Ye s 40 30 Weight Watchers Yes 30 50 Western Union Yes 30 20 Yum Brands No 27 21

question asked whether femvertising award-winning com-

initiatives), with 14 out of 15 internal initiatives present.

panies were more likely to have (a) more women on their

Kelloggs (non-award winning) and REI (award-winning)

board and (b) more women in leadership positions. These

had the greatest number of external initiatives, with seven

frequencies are reported in Table . O 3 f the 61 companies

out of eight possible efforts. Additionally, a majority of the

analyzed, two (Ascena Retail and GM) had boards with at

organizations (61%) reported the number of women within

least 50% women. Three companies (Ascena Retail, Rev- the organization.

lon, and Weight Watchers) had at least 50% women in their

Some significant differences were found between award leadership positions.

winners and non-award winners across the various types of

A multiple analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was per-

internal and external CSR activities. Pearson Chi-square and

formed with four dependent variables (internal efforts, exter-

crosstabulation analyses revealed that award-winning com-

nal efforts, women on the board, and women in leadership)

panies were more likely to have internal efforts regarding a

while controlling for the number of employees at a company

signed public agreement to gender equality within the com-

and annual revenue. While the omnibus test was not signifi-

pany and gender-equality trainings beyond those standard

cant for the effect of having won an award, F(4, 47) = 1.61,

for sexual harassment, p < 0.05. Award-winning companies

p = 0.19, the univariate test for the number of internal efforts were also more likely to engage in the external initiative of

was statistically significant, F(1, 50) = 6.56, p < 0.05, indi-

supporting or partnering with a non-profit, p = 0.05.

cating that companies that won an award had more inter-

nal efforts dedicated to supporting women (M = 5.04, Internal Activities

SD = 2.83) than companies that had not won a femvertising

award (M = 3.67, SD = 3.21). No other significant differences Among the internal CSR programs and actions, the most

emerged for the number of external efforts, women on the

popular activity was having employee resource groups

board, or women in leadership positions. Twenty five of the

(ERGs) for women, including affinity, mentoring, and net-

award-winning companies (81%) engaged in less than ten of

working groups, which 62% of the organizations utilized.

the possible 23 female empowerment activities. Four were

Next, 43% of the organizations had support programs for

engaged in 10 to 12 actions, and only two (GM and P&G)

women in the supply chain, such as Hershey’s “Cocoa for

engaged in more than half of the identified actions, with 13

Good” program which provides training and financial sup- and 15 actions, respectively.

port for cocoa farmers with a goal to economically empower Research Question 3

women in the supply chain. Many companies (39%) also had

programs focused on recruiting female workers.

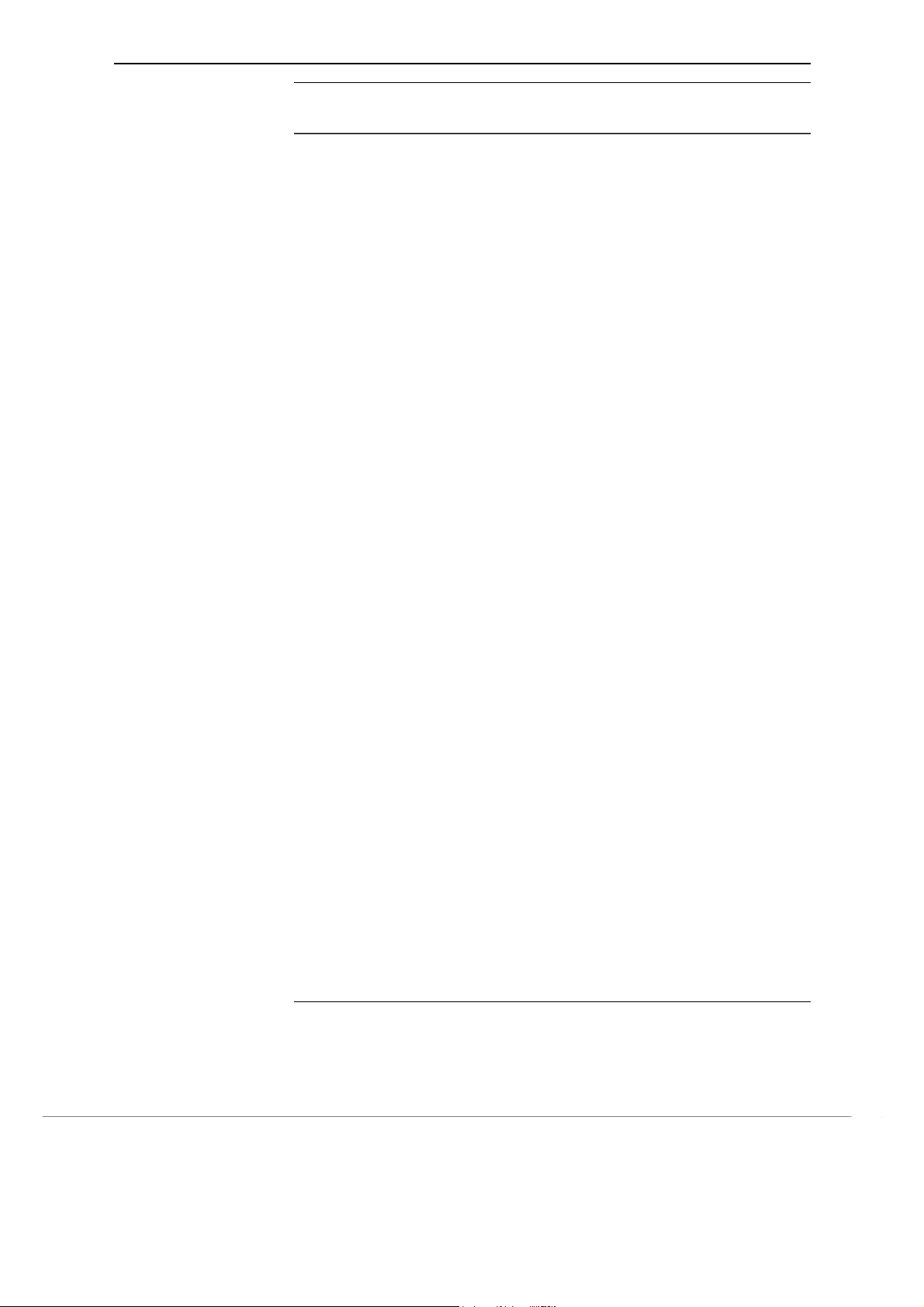

RQ3 explored which types of CSR activities were engaged

Among the internal CSR programs and actions, the least

in most and least often by award-winners, non-award win-

popular actions were setting measurable goals to increase

ners, and overall in the entire sample (see Table ) 4 . Of the

female representation at lower levels of the company (10%),

internal and external efforts included in the current study,

and initiatives to work with other businesses, suppliers, and

no company was found to engage in every possible ini-

partners that are gender-inclusive (7%). Changes of policy in

tiative. Walmart, a non-award-winning company, had the

the hiring process (12%) were also reported by few organiza-

most gender-equality initiatives in total (18 out of 23 total

tions. Companies were slightly more likely to set goals for 1 3 Y.Sterbenk et al.

Table 4 Frequencies of each CSR activity CSR activity Total companies Femvertising Non-award Chi-square value

engaging in activities award winners winners (%) (%) (%) Diversity reporting 61 52 70 2.16 Internal

Women in leadership pipeline initiatives 34 32 37 0.13

Measurable goals to increase female representation on board or 15 19 10 1.06 leadership

Measurable goals to increase female representation at lower levels 10 13 7 0.67

Programs focused on recruiting female workers 39 48 30 2.16

Internal events focused on gender issues and empowerment 34 32 37 0.13

HR Benefits + Policy changes aimed at gender equality 31 42 20 3.42

Signing a public commitment to gender equality inside the company 23 36 10 5.60*

Pay equality initiatives or commitments 25 26 23 0.05

Company states of changes their policy on hiring process 12 16 7 1.34

Employee Resource Groups, affinity groups, mentoring or networking 62 58 67 0.48 groups for women

Committee, employee or department formally coordinating gender 21 26 17 0.76 diversity and inclusion

Initiatives to work with other businesses, suppliers, partners that are 7 7 7 < 0.01 gender-inclusive

Sourcing from women-owned businesses 28 29 27 0.42

Support programs for women in the supply chain 43 45 40 0.17

Gender bias training that goes beyond sexual harassment training 30 42 17 4.68* External

Support for non-profit women’s organizations, NGOs, non-profits that 43 55 30 3.85*

focus on gender or women’s issues

Company scholarships and grants program (given directly to women) 28 29 27 0.04

Company programs that benefit women in the community 39 42 37 0.18

Company programs that benefit girls in the community 41 45 37 0.46

Producing advertising/marketing to celebrate women or work to 18 26 10 2.58

reduce gender stereotypes (beyond current femvertisement)

Diversifying or rethinking product lines aimed at expanding gender 10 13 7 0.67

reach or addressing gender stereotypes

Conversing with female consumers to meet their needs, specifically 10 3 17 3.11

Initiatives that encourage their industry or help other businesses to 13 10 17 0.65 address gender equality *p ≤ 0.05

gender representation in leadership and board positions, with companies. For example, Coca-Cola partnered with UN 15% reporting that goal.

Women to build technical knowledge among women farm-

ers, and it partnered with the UK Department for Interna- External Activities

tional Development to develop a program called “Educat-

ing Nigerian Girls in New Enterprises,” which improves

In terms of external CSR programs and actions, 43%

girls’ educational opportunities and potential for future

of organizations engaged in support for non-profits and success.

NGOs that focus on gender or women’s issues. For exam-

The least utilized external CSR programs and actions

ple, Kimberly-Clark partnered with Catalyst, a global

were conversing with female consumers to meet their

non-profit helping to build workplaces that work for

needs, which only 10% of the companies reported. Also,

women. Company programs that benefit girls (41%) and

only 10% of the companies in the sample diversified or

women (39%) in the community were also used by many

rethought their product lines to address gender stereotypes 1 3

Is Femvertising theNew Greenwashing? Examining Corporate Commitment toGender Equality

or expand their gender reach. Few companies engaged in

did they have greater female representation on their boards

efforts to encourage the industry or other businesses to

or in leadership positions. Wagner and colleagues (2009) address gender equality (13%).

argue that corporate hypocrisy happens when company

statements are inconsistent with observed behaviors, which

appears to be the case for many of award-winning compa- Discussion

nies. While more research is needed in this area, we pose

the term “fempower-washing” to describe CSR-washing in

The purpose of this study was to examine the presence of

the context of gender equality. Akin to greenwashing, it is

CSR-washing among companies that have and have not

important that researchers continue to monitor the use of

been recognized for their female empowerment adver-

fempower-washing in industry practice and award compe-

tisements (“femvertisements”). While limited by a small

titions before companies begin to inundate consumers with

sample size, award-winning companies exhibited external

false perceptions. While many female consumers report

CSR commitment, as well as female leadership, similar

enjoying these advertisements (such as the Fearless Girl

to companies that had not received a femvertising award.

statue), companies can quickly come under fire with the

Given the increased level of consumer scrutiny that can

public when their lack of internal and external CSR activi-

follow CSR advertising (Madrigal and Boush ; 2008 Dawk-

ties to support women are discovered (i.e., the subsequent

ins 2004; Yoon etal. 2006; Cone Communications 2017),

backlash State Street Global Advisors encountered after

it was surprising to observe few differences between the

commissioning the Fearless Girl, due to multiple issues

two groups of companies. Firms must choose to submit

within the organization related to gender equality).

their ads for award consideration, which suggests they feel

For only one of these initiatives (supporting a non-

confident in their message. In some cases, non-award-win-

profit) did award-winning companies engage in signifi-

ning companies engaged in more types of gender-equality

cantly more external efforts than non-award-winning com-

actions than companies receiving an award. However,

panies. It is worth noting that award-winning companies

when controlling for the number of employees at a given

committed to more external activities in six of the eight

company and annual revenue, femvertising award win-

categories; however, these were not significantly different.

ners committed to more internal efforts devoted to gender

These companies may experience backlash from female equality.

consumers, who may not be privy to a company’s internal

efforts and programs for women. It may be invaluable for

Award‑Winning Companies Do More Internally

companies with many internal programs to better com-

municate these efforts through public-facing channels such

When looking at companies of roughly the same size (num- as their website.

ber of employees) and financial resources (annual revenue),

Greenwashing has been found to occur most often

those that won a femvertising award were indeed more com-

through the use of vague statements and symbolic imagery

mitted to supporting women in meaningful ways, at least

in advertising that suggest positive environmental associa-

internally. It may be that award-winning companies are more tions (Kangun etal ; 1991 Parguel etal ) 2015 , and a similar

likely to produce femvertisements that are high caliber, and

case may be made for many of the award-winning femver-

thus win awards, because they have more internal efforts

tisements. Ultimately, however, the public holds companies

and programs that focus on women and perhaps have a bet-

accountable for the statements made in their advertisements

ter understanding of women’s experiences. This coincides

and avidly uses social media to discuss brands and their with findings from Hughes ( ) 2013 , which suggested that

decisions to communicate about social issues (Passifiume

advertisements are more effective with employees when

2019). Companies take a risk by “talking” about women’s

they are also backed by internal company communications

empowerment in their advertisements, but not “walking the

and actions. In this study, it appears the reverse may be

walk” by investing in a breadth of programs or other efforts

true—internal efforts can perhaps make for better (award-

dedicated to supporting women. Previous research suggests

winning) advertisements; however, research is needed to test

that this can have a negative impact on reputation and on this proposition.

stakeholder trust (Wagner etal. ; 2009 Kim etal. ; 2015 Yoon

etal. 2006). However, findings from this study suggest that

Emerging Evidence ofCSR‑Washing

consumers and industry leaders alike continue to award com-

panies for their advertisements, giving less or little attention

Despite having an award-winning external effort (femver-

to the programs and other initiatives that work to actually

tisement), companies who won an award for femvertis-

move the needle for gender equality. This supports recent

ing did not engage in significantly more types of external

work by Abitbol and Sternadori ( ) 2019 who found that par-

efforts (in total) than non-award-winning companies, nor

ticipants had positive responses to femvertisements, even for 1 3 Y.Sterbenk et al.

companies who were currently experiencing public lawsuits

that the two measurable goals examined in this study were

related to gender equality. Consumers say they will research

among the lowest used CSR activities. Only 15% of compa-

companies to evaluate their CSR initiatives (Cone Commu-

nies had measurable goals for women in board or leadership nications 2017), but do they?

positions, and only 10% had measurable goals for women’s

Based on previous research that shows companies with

representation at lower levels in the organization. Companies

more women in leadership roles tend to exhibit greater cor-

were more likely to adopt looser activities for building the

porate responsibility activity (Cook and Glass ; 2018 Setó‐

pipeline, such as internal events focused on gender issues

Pamies 2015; Macaulay etal. 2018) and focus on gender

and empowerment (34%) and programs focused on recruit-

equality, we assumed that having more women in leadership ing female workers (39%).

at the company would result in more programs for women,

Upon examination of the most and least popular exter-

but this was not the case. This is an important takeaway

nal initiatives, the most popular seem to be those which

as it suggests that companies may be tokenizing women in

are designed to support NGOs and non-profits that support

higher management and leadership positions. Women might

women (43%) or those programs that benefit girls (41%) and

be given these opportunities as a way for the company to

women (39%) in the community. These initiatives are tailor

appear equitable, while still lacking a deep commitment to

made for publicity about doing good for women in the com-

gender-equality motives. Future research could address bar-

munity, as they lend themselves to feel-good stories, news

riers perceived by upper-management female leaders to add

releases, and annual report fodder. These kinds of initiatives

additional clarity to these findings.

are more likely to address stakeholder interests, and thus fall

into the category of “promotional CSR” (Pirsch etal. 2007).

Level ofCommitment andGoals fortheFuture

They also take a paternalistic view, in which the organization

is in the position of power supporting women and girls in

In exploring greenwashing, Walker and Wan ( ) 2012 sug-

the community. Meanwhile, two of the least popular external

gested that it would be “extremely difficult” for firms to

initiatives concerned listening to female consumers to assess

engage in all categories of environmental action (p. 237).

their needs (10%) and rethinking product lines to overcome

Based on the results of this study, this could be true for

gender stereotypes (10%), both which require recognition

female empowerment as well. In reviewing the most com-

of women and their perspectives. Initiatives to partner with

mon kinds of internal actions taken by companies in our

other businesses to address gender equality (13%) were also

femvertising sample, it is clear that many have committed

rarely seen in the sample. These three unpopular external

to more easily implemented activities such as forming net-

initiatives would more closely symbolize “institutionalized

working groups for female employees or increasing efforts to CSR,” which requires operationalized institutional commit-

recruit women. In contrast, fewer companies showed exist-

ment to the cause (Pirsch etal. ) 2007 .

ing commitments toward critical—and harder—aspects of

This study builds on the limited research on CSR-washing

gender equality, such as supporting women at lower levels

and corporate hypocrisy (Pope and Waeraas ; 2015 Wagner

in the company or fostering female representation in board

etal. 2009) and applies the concept in a new context: gen-

and leadership positions. While many companies are willing

der equality. There exists a great deal of research regarding

to report current gender numbers, fewer have publicly com-

green advertising and greenwashing claims and the impact

mitted to measurable objectives for gender diversity. This

of greenwashing on reputation (e.g., Nyilasy etal ; 2014 Ber-

demonstrates Argenti’s (2016) argument that, regarding CSR rone etal. )

2017 . However, it is important to address these

programs overall, more companies “tend to rely on lagging

practices within the growing body of research and practice

indicators (which reflect changes and confirm long-term

related to femvertising messages and reception (Abitbol and

changes) when evaluating the effects of their businesses on Sternadori 2019; Feng etal ; 2019 Sobande ; 2019 Champlin

social and environmental issues, failing to consider lead-

etal. 2019). Several of the companies included in the present

ing indicators (which predict or signal future events)” (p.

study target mostly women, such as award-winning Coty (the

334). He encourages the use of both lagging and leading

parent company of CoverGirl, OPI, Rimmel, and other cos-

indicators, as together they provide a clearer picture of the

metics brands) and non-award-winning Revlon. These com-

way corporate activity impacts results. In fact, specific,

panies have an opportunity to lead the charge in supporting

measurable goals are generally thought to be a best practice

gender equality. Yet, through the present study, both of these

for strategic communication (e.g., Moriarty 1996; Schultz

companies were found to have only minimal gender-equality and Barnes )

1995 , because they suggest a goal has been set

efforts (Coty had four internal efforts and Revlon had one;

against which strategy can be developed and efforts can be

neither had any external female empowerment activities).

measured. Thus, we might assume the presence of measur-

able objectives toward gender equality is a strong signal that

an organization is serious about equality. It is noteworthy 1 3

Is Femvertising theNew Greenwashing? Examining Corporate Commitment toGender Equality

Limitations andFuture Research

impact of their actions can also provide a fuller picture of corporate commitment.

This study opens up paths for future research. First, this

research examined US-based companies, and could thus be

expanded to provide an international view. Social norms and

Conclusion andImplications

policies related to rights for women in the workplace differ

across countries and could thus play a role in the CSR efforts Previous research suggests that CSR-washing is not all that

observed. More globally-based research is certainly needed. common (Pope and Waeraas ) 2015 . Moreover, a majority

Additionally, with the growth in the number of brands hop-

of the literature on CSR-washing focuses on the topic of

ing to align themselves with social issues, it is critical that

greenwashing, while other forms of CSR-washing have not

additional research be conducted to see how CSR-washing

been given similar attention. Companies who develop fem-

applies to other social issues addressed in advertising, such

vertisements face increased scrutiny from critics over their

as race, disability, and LGBTQ+ rights.

commitment to gender equality, yet also they are rewarded

This project implemented an existing framework to build

and applauded through industry awards, and their videos are

and analyze profiles of CSR activities (de Jong and van der

shared by consumers. This study takes a first step in examin-

Meer 2015). Similar to that work, the present study is limited ing whether there exists a relationship between a company’s

in that the focus was on CSR reports provided by the com-

commitment to gender equality and their tendency to use

panies themselves. de Jong and van der Meer (2015) suggest

femvertisements to promote their connection to the cause

also including stakeholder interviews from the correspond-

of female empowerment. Based on the information avail-

ing companies. Furthermore, the current project examined

able, a majority of the award-winning companies engaged

and implemented all of the existing lists of award-winning

in corporate hypocrisy, because, beyond their ad campaigns,

femvertisements. No other lists were available to draw from;

they did little to contribute to gender equality within their

however, the study remains limited in sample size. Regard-

company. Just as companies engaged in greenwashing ads

less of sample size, the means for award-winning and non-

due to consumer trends in environmentalism, so have com-

award-winning companies for all four dependent variables

panies engaged in femvertising due to trends for equality.

were nearly identical between the two groups.

This study represents an initial examination of companies’

Because this study focused on evidence of the types of

commitment, which can provide guidance for future research

gender-related activities included in the companies’ self-

and for companies who wish to commit more fully.

reporting, it was difficult to distinguish the depth of each

company’s commitment across the CSR activities. For

instance, some companies, like P&G, engaged deeply in

Compliance with Ethical Standards

a multitude of actions that help women in the community,

while others only employed one or two efforts. Future

Conflict of interest The authors of this paper have no conflicts of inter-

ests to disclose, and are in compliance with ethical standards.

research could report on the total number of activities

reported by each company to assess its commitment to gen-

der equality. It would also be useful to examine the language References

used to communicate gender-related CSR actions to gauge

the true sentiment and commitment of the companies to the

Abitbol, A., & Sternadori, M. (2019). Championing women’s empow-

cause as it aligns with the companies’ stated values.

erment as a catalyst for purchase intentions: Testing the mediat-

Finally, this study also only examined self-reported data

ing roles of OPRs and brand loyalty in the context of femvertising.

from the most recent year available. It is likely that compa-

International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(1), 22–41.

Akestam, N., Rosengren, S., & Dahlen, M. (2017). Advertising “like

nies are engaged in additional or other activities that are not

a girl”: Toward a better understanding of “femvertising” and its

highlighted in these reports. Bouten etal. ( ) 2011 suggest that

effects. Psychology & Marketing, 34, 795–806.

the most comprehensive picture of CSR can be seen through

Argenti, P. A. (2016). Corporate responsibility. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

self-reporting of vision and goals, management approaches, Publications Ltd.

Arvidsson, S. (2010). Communication of corporate social responsibil-

and performance indicators, and Hopkins ( ) 2005 says CSR

ity: A study of the views of management teams in large companies.

is measured by looking at a company’s principles of social

Journal of Business Ethics, 96 (3), 339–354.

responsibility, processes of social responsiveness, and

Bahadur, Nina. (2014). “Dove ‘Real Beauty’ Campaign Turns 10: How

outcomes of social responsibility. Some of the companies

a Brand Tried to Change the Conversation About Female Beauty.”

Huffington Post. Retrieved from https ://www.huffi ngton post.

included measurable goals related to gender representation,

com/2014/01/21/dove-real-beaut y-campa ign-turns -10_n_45759

as well as impact data from current and ongoing activities. 40.html.

Examining whether and how companies are measuring the 1 3 Y.Sterbenk et al.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact

on corporate financial performance. Public Relations Journal, 8(3).

of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior.

Retrieved January 2019: http://www.prsa.org/Intel ligen ce/PRJou

Journal of Business Research, 59, 46–53. rnal/Vol8/No3/

Begum, M. I. A. (2018). Corporate social responsibility and gender com- Donia, M., & Tetrault Sirsly, C. (2016). Determinants and consequences

mitments of commercial banks in Bangladesh. Journal of Interna-

of employee attributions of corporate social responsibility as sub-

tional Women’s Studies, 19(6), 87.

stantive or symbolic. (Report). European Management Journal.

Berrone, P., Fosfuri, A., & Gelabert, L. (2017). Does greenwashing pay

https ://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.02.004.

off? Understanding the relationship between environmental actions

Edelman (2017). 2017 Edelman earned brand study: Beyond no brand’s

and environmental legitimacy. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(2),

land. Retrieved from https ://www.edelm an.com/earne d-brand 363–379.

Eisend, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of gender roles in advertising. Journal

Blay, Z. (2016, June 23). Axe and Dove parent company promises no

of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(4), 418–440.

more sexist ads after bleak report. Huffington Post. Retrieved from

Femvertising (n.d.), Femvertising Awards. Retrieved from https ://www.

https ://www.huffi ngton post.com/entry /axe-and-dove-par e n t-compa femve rtisi ngawa rds.com/.

ny-promi ses-no-more-sexis t-ads_us_576bf 003e4 b0b48 9bb0c 85c7.Feng, Y., Chen, H., & He, L. (2019). Consumer responses to femvertis-

Bouten, L., Everaert, P., Van Liedekerke, L., De Moor, L., & Christiaens,

ing: A data-mining case of Dove’s “Campaign for Real Beauty”

J. (2011). Corporate social responsibility reporting: a comprehensive

on YouTube. Journal of Advertising, (

48 3), 292–301. https ://doi.

picture? Accounting Forum, 35(3), 187–204.

org/10.1080/00913 367.2019.16028 58.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2006). Firm size, organizational vis-

Fischer, D. (2020). The three dimensions of sustainability: A delicate

ibility and corporate philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Business

balancing act for entrepreneurs made more complex by stakeholder

Ethics: A European Review, 15(1), 6–18. https ://doi.org/10.111

expectations. Journal of Business Ethics, 163(1), 87–106. https :// 1/j.1467-8608.2006.00424 .x.

doi.org/10.1007/s1055 1-018-4012-1.

Browning, N., Gogo, O., & Kimmel, M. (2018). Comprehending CSR

Glass: The Lion for Change. (n.d.). Retrieved from Cannes Lions: https

messages: Applying the elaboration likelihood model. Corporate

://www.canne slion s.com/enter /award s/good/glass -the-lion-f or-chang Communications, 23 (1), 17–34. e#/

Carter, M. (2015). Backlash against “pinkwashing” of breast cancer

Holder-webb, L., Cohen, J., Nath, L., & Wood, D. (2009). The supply of

awareness campaigns. (Report). British Medical Journal, 351(8029).

corporate social responsibility disclosures among U.S. firms. Jour-

Castaldo, S., Perrini, F., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2009). The missing

nal of Business Ethics, 84 (4), 497–527.

link between corporate social responsibility and consumer trust: The Holman, J. (2017, Oct 05). Bank behind fearless girl statue settles gender

case of fair trade products. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–15. 64,

pay dispute. Bloomberg Wire Service. Retrieved from https ://www.

Castillo, M. (2014). These stats prove femvertising works. AdWeek,

bloom berg.com/ne ws/artic les/2017-10-05/bank-behin d-fearl ess-girl-

Retrieved from https ://www.adwee k.com/digit al/these -stats -prove

statu e-settl es-u-s-gende r-pay-dispu te

-femve rtisi ng-works -16070 4/

Hopkins, M. (2005). Measurement of corporate social responsibility.

Champlin, S., Sterbenk, Y., Windels, K., & Poteet, M. (2019). How brand-

International Journal of Management and Decision Making, 6(3–4),

cause fit shapes real world advertising messages: A qualitative explo- 213–231.

ration of “femvertising”. International Journal of Advertising, 38(8), Hsu, C. (2018a). Femvertising: State of the Art. Journal of Brand Strat-

1240–1263. https ://doi.org/10.1080/02650 487.2019.16152 94.

egy, 7(1), 28–47.

Chatterji, A. K., & Toffel, M. W. (2016, April 3). The power of C.E.O.

Hsu, T. (2018b, August 10). Ex-employees sue Nike, alleging gender

activism. New York Times, p. SR10. Retrieved March 22, 2018, from

discrimination. New York Times. Retrieved from https ://www.nytim

https ://www.nytim es.com/2016/04/03/opini on/sunda y/the-po wer -of-

es.com/2018/08/10/busin ess/nike-discr imina tion-class -actio n-law su ceo-activ ism.html it.html

Cone Communications. (2015). New Cone Communications research

Hughes, D. (2013). This ad’s for you: The indirect effect of advertising

confirms Millennials as America’s most ardent CSR supporter,

perceptions on salesperson effort and performance. Journal of the

but marked differences revealed among this diverse generation.

Academy of Marketing Science, 41(1), 1–18. https ://doi.or g/10.1007/

Retrieved from: http://www.conec omm.com/news-blog/new-cone- s1174 7-011-0293-y.

commu nicat ions-resea rch-confi rms-mille nnial s-as-ameri cas-most-Jones, O. (2019, May 23). Woke-washing: how brands are cashing in arden t-csr-suppo rters

on the culture wars. The Guardian. https ://www.thegu ardia n.com/

Cone Communications. (2016). 2016 Millennial Employee Engagement

media /2019/may/23/woke-washi ng-Brand s-cashi ng-in-on-cultu

Study. Retrieved from: http://mille nnial emplo yeeen gagem ent.com/ re-wars-owen-jones

Cone Communications. (2017). Brands & Social Activism: What Do You Kangun, C., Carlson, L., & Grove, S. (1991). Environmental advertis-

Stand Up For? Retrieved from: https ://stati c1.squar espac e.com/stati

ing claims: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Public Policy

c/56b4a 7472b 8dde3 df5b7 013f/t/5947d bcf4f 14bc4 eadcd 025d/14978 & Marketing, 10

(2), 47–58. https ://doi.org/10.1177/07439 15691

81572 759/CSRIn fogra phic+FINAL 2.jpg 01000 203.

Cook, A., & Glass, C. (2018). Women on corporate boards: Do they

Kim, H., Hur, W., & Yeo, J. (2015). Corporate brand trust as a mediator

advance corporate social responsibility? Human Relations, 71(7),

in the relationship between consumer perception of CSR, corporate

897–924. https ://doi.org/10.1177/00187 26717 72920 7.

hypocrisy, and corporate reputation. Sustainability (Basel, Switzer-

Dawkins, J. (2004). Corporate responsibility: The communication chal-

land), 7(4), 3683–3694. https ://doi.org/10.3390/su704 3683.

lenge. Journal of Communication Management, 9(2), 108–119.

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2008). Qualitative data analysis:

de Jong, M., & van Der Meer, M. (2015). How does it fit? exploring the

A compendium of techniques and a framework for selection for

congruence between organizations and their corporate social respon-

school psychology research and beyond. School Psychology Quar-

sibility (CSR) activities. Journal of Business Ethics, ( 143 1), 71–83.

terly, 23(4), 587.

Delmas, M., & Burbano, V. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. Cali-

Madrigal, R., & Boush, D. M. (2008). Social responsibility as a unique

fornia Management Review, 54(1), 64–87.

dimension of brand personality and consumers’ willingness to

Diaz, A. C., & Zmuda, N. (2014). Less talk, more women at the top.

reward. Psychology & Marketing, 25, 538–564.

Advertising Age, 85(18), 17.

Macaulay, C. D., Richard, O. C., Peng, M. W., & Hasenhuttl, M. (2018).

Dodd, M. D. & Supa, D. W. (2014). Conceptualizing and measuring

Alliance network centrality, board composition, and corporate social

“corporate social advocacy” communication: examining the impact

performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(4), 997–1008. 1 3

Is Femvertising theNew Greenwashing? Examining Corporate Commitment toGender Equality

Mahdawi, A. (2018, August 10). Woke-washing brands cash in on social Sobande, F. (2019). Woke-washing: “intersectional” femvertising and

justice. It’s lazy and hypocritical. The Guardian. https ://www.thegu

branding “woke” bravery. European Journal of Marketing. https ://

ardia n.com/comme ntisf ree/2018/aug/10/fello w-kids-woke-washi ng-

doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0134.

cynic al-align ment-worth y-cause s

Storbeck, O. (2017, February 6). Audi’s gender equality plea lacks horse-

Mitchell, A. & Ward, R. (2010). Rainbow washing schools: Are primary

power. Reuters. Retrieved January 15, 2020, from https ://www.reute

schools ready for same-sex attracted parents and students? Gay and

rs.com/artic le/uk-super -bowl-audi-break ingvi ews-idUSK BN15L

Lesbian Issues and Psychology Review, 6(2), 103–106. Retrieved 17C

from http://searc h.proqu est.com/docvi ew/85961 3952/

Think with Google. What women watch: Trends toward entrepreneurship,

Modiba, E., & Ngwakwe, C. (2017). Women on the corporate board of

education, and empowerment on YouTube. (2017, March). Retrieved

directors and corporate sustainability disclosure. Corporate Board:

May 7, 2020, from https ://www.t hink wit hg oogle .com/consu mer-

Role, 13(2), 32–37.

insig hts/marke ting-to-women -empow ering -ads/

Moriarty, S. E. (1996). Effectiveness, objectives and the EFFIE awards.

Udayasankar, K. (2008). Corporate social responsibility and firm size.

Journal of Advertising Research, 36(4), 54.

Journal of Business Ethics, 83(2), 167–175. https ://doi.org/10.1007/

Nyilasy, G., Gangadharbatla, H., & Paladino, A. (2014). Perceived green- s1055 1-007-9609-8.

washing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate

Varghese, N., & Kumar, N. (2020). Femvertising as a media strategy

environmental performance on consumer reactions. Journal of Busi-

to increase self-esteem of adolescents: An experiment in India. ness Ethics, 125 (4), 693–707.

Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 104965. https ://doi.

Obermiller, C., & Spangenberg, E. (1998). Development of a scale to

org/10.1016/j.child youth .2020.10496 5.

measure consumer skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Con-

Varghese, N., & Kumar, N. (2020). Feminism in advertising: irony or

sumer Psychology, 7(2), 159–186.

revolution? A critical review of femvertising. Feminist Media Stud-

Obermiller, C., Spangenberg, E., & MacLachlan, D. L. (2005, Fall).

ies. https ://doi.org/10.1080/14680 777.2020.18255 10.

Ad skepticism: the consequences of disbelief. Journal of Adver-

Wagner, T., Lutz, R. J., & Weitz, B. A. (2009). Corporate hypocrisy:

tising, 34(3), 7. Retrieved from https ://link-galeg roup-com.ezpro

Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility

xy.ithac a.edu/apps/doc/A1378 61176 /AONE?u=nysl_sc_ithac

perceptions. Journal of Marketing, 73, 77–91.

a&sid=AONE&xid=87541 58a

Waller, D. S., & Lanis, R. (2009). Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Parguel, B., Benoit-Moreau, F., & Russell, C. (2015). Can evoking nature

disclosure of advertising agencies. Journal of Advertising, 38(1),

in advertising mislead consumers? The power of “executional green- 109–121.

washing.” International Journal of Advertising, 34 (1), 107–134.

Walker, K., & Wan, F. (2012). The harm of symbolic actions and green-

https ://doi.org/10.1080/02650 487.2014.99611 6.

washing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental

Passifiume, B. (2019, January 17). Backlash to Gillette ’toxic masculinity’

performance and their financial implications. Journal of Business

ad spreads on social media. Toronto Sun. Retrieved Oct. 29, 2019, Ethics, 109 (2), 227–242.

from https ://toron tosun .com/news/world /onlin e-backl ash-to-gille Webb, D. J., & Mohr, L. A. (1998). A typology of consumer responses to

tte-toxic -mascu linit y-ad-sprea ds-on-socia l-media

cause-related marketing: From skeptics to socially concerned. Jour-

Pirsch, J., Gupta, S., & Grau, S. (2007). A framework for understand-

nal of Public Policy and Marketing, 17(2), 226–238.

ing corporate social responsibility programs as a continuum: An

Windels, K., Champlin, S., Shelton, S., Sterbenk, Y., & Poteet, M. (2020).

exploratory study. Journal of Business Ethics, ( 70 2), 125–140.

Selling feminism: How female empowerment campaigns employ

Pomering, A., & Johnson, L. (2009). Constructing a corporate social

postfeminist discourses. Journal of Advertising, 49(1), 18–33. https

responsibility reputation using corporate image advertising. Aus-

://doi.org/10.1080/00913 367.2019.16810 35.

tralasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 17(2), 106–114.

Wired staff. (2018, June 21). The Problem With the ’Rainbow-Washing’

Pomering, A., Johnson, L., & Noble, G. (2013). Advertising corporate

of LGBTQ+ Pride. Wired.com. https ://www.wired .com/story /lgbtq

social responsibility. Corporate Communications, 18(2), 249–263. -pride -consu meris m/

Pope, S., & Waeraas, A. (2015). CSR-washing is rare: A conceptual

Wojcicki, S. (2016, April 24). Ads that empower women don’t just break

framework, literature review, and critique. Journal of Business Eth-

stereotypes—They’re also effective. Adweek. Retrieved April 23, ics, 137 (1), 173–193.

2020, from https ://www.adwee k.com/brand -marke ting/ads-empow

Schultz, D. E., & Barnes, B. E. (1995). Strategic advertising campaigns

er-women -don-t-jus t-break -stere otype s-they-re-also-effec tive-17095

(4th ed.). Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Business Books. 3/

Setó-Pamies, D. (2015). The relationship between women directors

Wolin, L. D. (2003). Gender issues in advertising: An oversight synthesis

and corporate social responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibil-

of research: 1970–2002. Journal of Advertising Research, 43 (1),

ity and Environmental Management, 22(6), 334–345. https ://doi. 111–129. org/10.1002/csr.1349.