Preview text:

CHAPTER 6

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates fic.com 6.1. Introduction

The asset market model of exchange rate determination underwent consid-

erable development during the first decade following the floating of major

currencies (1973–83). This is because simple models were found to explain

the behavior of the post-Bretton Woods floating exchange rates poorly and

also because the availability of a larger set of data on the floating period

provided the opportunity to carry out more empirical work.1 The very high

volatility of the real exchange rates of major currencies in the late 1970s

casts doubt on PPP and inspired the development of further versions of the

monetary model, including the sticky-price monetary model of Dornbusch (1976c).

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, a wide range of overshooting

models were constructed to explain new stylized facts or events asso-

ciated with the floating rate period. Included in these models are the real

interest differential sticky-price monetary model of Frankel (1979b), the

stock-flow model of Driskell (1981), and the equilibrium real exchange

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

rate sticky-price model of Hooper and Morton (1982). Yet, the empirical

validity of these variants of the sticky-price model has proven to be more

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti elusive.

In the simple flexible-price model, the exchange rate is determined by

stock equilibrium in money markets, which is achieved very quickly (if not

instantaneously) through continuous adjustment of prices in the goods and

asset markets, while complete neutrality of monetary policy is maintained

1For a detailed analysis of the development of the asset-market model of exchange rate

determination and the events of the current floating rate period leading to modifications and

extensions in the theory, see Dornbusch (1980b) and Shafer et al. (1983). 186

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 187

on a continuous basis. This model appears to fit the data fairly well for the

first four years of flexible exchange rates (1973–76), as indicated by the

evidence presented by Hodrick (1978) and Bilson (1978a). In subsequent

studies (which tested the model for a slightly larger set of data incorporating

the period 1977–78), the performance of this model deteriorated severely.

This led to considerable concern with respect to a reconciliation of the

simple monetary model with the observed large fluctuations in exchange rates.

By late 1975, little correspondence was found between exchange rates

and prices in many major industrial countries (at least in the short run) and it fic.com

was also found that changes over time in the real exchange rates were much

larger than those under fixed exchange rates. Inflation rates diverged widely

between these countries, while exchange rates showed some tendency to

change over time to contain deviation from purchasing power parity. Never-

theless, most fluctuations in nominal exchange rates over the period March

1973 to September 1975 were reflected in the movements of real exchange

rates. It was against this backdrop that Dornbusch (1976c) developed the

sticky-price version of the monetary model. This model is consistent with

several stylized facts that do not fit well with the flexible-price model. Not

only does it rationalize deviations from purchasing power parity in the short

run, it also provides an explanation for periods when a rising nominal interest

rate is associated with a strong currency. In the flexible-price model, a rise in

the nominal interest rate is always associated with an increase in the inflation

rate and more rapid depreciation (or less rapid appreciation) of the currency.

In the sticky-price model, a persistently higher level of the interest rate

reflects higher inflation, which makes it associated with a weaker currency.

But an increase in the interest rate and declining inflationary expectations

may be produced by a shift to tight monetary policy, leading to currency

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only. appreciation.

The sticky-price model suggests that the relation between changes in

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

the exchange rate and monetary aggregates is not simple even when mon-

etary disturbances are the underlying cause. Expectations concerning future

levels of the money supply are more important than the current levels of

the money supply, which means that poor correlation between contempora-

neous changes in monetary aggregates and exchange rates is explainable. It

must be noted, however, that evidence on the sticky-price model is not very

much different from the evidence on the flexible-price model, particularly

during the first 4 years of the current flexible exchange rate period. This is 188

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates

why the empirical basis for a choice between the flexible- and sticky-price

versions of the monetary model is not clear.

Frankel (1979b) modified the Dornbusch (1976c) sticky-price model by

allowing a role for differences in secular inflation rates, hence including the

real interest differential as an additional explanatory variable. He argues

that changes in long-term nominal interest rates are a measure of changes

in inflation expectations. According to this view, only short-term interest

rates are viewed as moving somewhat independently of inflation. Therefore,

Frankel includes the long-term interest rate differential in the exchange

rate equation either because long-term interest rates measure the cost of fic.com

holding money or because they are considered as a proxy for the anticipated

inflation differential. In either view, a rise in the domestic long-term interest

differential leads to a reduction in real money demand and thus to higher

prices and currency depreciation.

Frankel (1979b) tested the real interest differential model for the

mark/dollar rate from July 1974 to February 1978 and found evidence

that clearly supported the model against the flexible- and the sticky-price

versions of the monetary model. However, subsequent attempts by Dorn-

busch (1980b), Haynes and Stone (1981), and Frankel (1981) to explain

movements in the mark/dollar exchange rate after February 1978 were

unsuccessful, showing insignificant coefficients and a “reversed sign” on

the relative money coefficient. An important phenomenon that was not

directly explainable by the sticky-price models of Dornbusch (1976c) and

Frankel (1979b) was the large and growing deficit in the U.S. current

account and the surpluses of Germany and Japan. Many observers began

to view the 1978–79 slide of the U.S. dollar as primarily an adjustment

to this large and growing deficit in the U.S. current account and sur-

pluses in Germany and Japan.2 In early 1975, a surplus arose in the U.S.

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

current account as the sharp U.S. recession reduced imports. But with the

recovery of the economy and the dollar, the current account began to decline

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

rapidly. This phenomenon induced many economists to turn to models

that assign a role to the current account in the process of exchange rate determination.

One popular model that gives a role to the current account in exchange

rate determination is the equilibrium real exchange rate model of Hooper

2Note that current account imbalances have been larger and more volatile during the floating

period than they had been during the Bretton Woods period.

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 189

and Morton (1982).3 They modified the Dornbusch–Frankel sticky-price

models by allowing large and sustained changes in real exchange rates,

which are related to movements in the current account (both through

changes in expectations about the long-run real exchange rate and through

changes in the risk premium). In particular, they show that the equilibrium

real exchange rate (defined as the rate that is consistent with the long-

run current account balance) can be expressed as a function of the initial

equilibrium rate and the cumulative sum of past non-transitory unexpected

changes in the current account. Hooper and Morton (1982) tested this fic.com

model empirically for the dollar’s weighted average exchange rate (against

the currencies of Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the

Netherlands, Sweden, and the U.K.) over the flexible rate period of 1973–

78. They obtained results indicating that the current account affected the

exchange rate predominantly through its impact on expectations about the

long-run equilibrium real exchange rate. According to them, these results

are a reflection of the period extending between the end of 1976 and the end

of 1978, when the dollar depreciated steadily in real terms as the U.S. ran

a series of large current account deficits.

Frankel (1982a) adopts an alternative strategy to take account of the

role of the current account in the Dornbusch–Frankel sticky-price model.

He modifies money market conditions (stated in terms of the domestic and

foreign money demand functions and the exchange rate equation) by adding

relative wealth as an additional explanatory variable. The logic underlying

this formulation goes as follows. A foreign current account surplus repre-

sents a redistribution of wealth from domestic residents to foreign residents,

simultaneously raising foreign money demand, lowering domestic money

demand, and raising the exchange rate.

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

3Other models that give a specific role to the current account in the determination of exchange

rates are the portfolio balance models that were originated by Branson (1976), Girton and

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

Henderson (1976), Kouri et al. (1978), Dooley and Isard (1979, 1982, 1983), Dornbusch

(1980a), and Allen and Kenen (1980). Within the theoretical framework of slowly adjusting

commodity prices, an alternative to Dornbusch’s view of exchange rate dynamics, the

portfolio balance models emphasize stock-flow interaction and relative-price trade-balance

effects. In contrast to the monetary models, domestic and foreign bonds are assumed to be

imperfect substitutes. Thus, an increase in a country’s wealth (which is caused by a surplus

in its current account) leads to an increase in the demand for domestic bonds and hence

appreciation of the domestic currency. For a detailed discussion of portfolio balance models, see Chapter 8. 190

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates

Another interesting variant of the sticky-price model (developed in

the context of the portfolio balance effect) is due to Driskell (1981). He

developed a stock-flow model that generalizes the Dornbusch (1976c)

model, permitting imperfect substitutability between domestic and foreign

assets and allowing trade flows to affect financial markets through the

balance of payments. In this model, portfolio allocation may affect the

exchange rate. He derives a reduced form exchange rate equation by

replacing the uncovered interest parity condition in Dornbusch’s (1976c)

framework with a balance of payments equation. fic.com

6.2. The Real Interest Differential Monetary Model

Frankel (1979b) argues that the flexible-price monetary model (what he

called the “Chicago theory of exchange rate”) and the sticky-price mon-

etary model (what he called the “Keynesian theory of exchange rate”) have

conflicting implications, particularly for the relation between exchange and

interest rates. In the following two subsections, the real interest differential model is described.

6.2.1. Moderate Inflation and the Exchange Rate

Expectations Scheme

The real interest differential model draws upon the sticky-price model by

assuming that while purchasing power parity fails to hold in the short run,

it is valid in the long run. The two models are similar except for the expec-

tation formation mechanisms. The mechanism used in the real interest dif-

ferential model postulates that the expected change in the exchange rate is a

function of (i) the gap between the current spot rate and the long-run equi-

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

librium rate and (ii) the expected long-run inflation differential. Formally,

this expectation formation mechanism is represented as follows:

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti E(s) = i − i∗ (6.1) E(s) = θ( ¯

s − s) + (pe − p∗e). (6.2)

Equation (6.1) states that (under perfect capital mobility) if there is no

uncertainty and if market participants are neutral, the expected rate of depre-

ciation of the domestic currency will be equal to the interest differential.

On the other hand, equation (6.2) states that in the short run, the exchange

rate (s) is expected to return to its long run equilibrium value ¯ s at a rate

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 191

that is proportional to the current gap. In the long run (when ¯ s = s), the

exchange rate is expected to change at a rate that is equal to the long-run

inflation differential (pe − p∗e), which is equal to the expected long-run

relative monetary growth rate that is known to the public. By combining

equations (6.1) and (6.2) and then solving for s, we obtain 1 s = ¯ s −

[(i − pe) − (i∗ − p∗e)]. (6.3) θ

Equation (6.3) shows that the exchange rate s tends to overshoot its long-run value ( ¯

s) when goods prices are sticky in the short run and to converge on fic.com

the long-run value when goods prices adjust in the long run. It must be noted

that the current exchange rate overshoots its long-run equilibrium value by

an amount that is proportional to the nominal interest differential in the

Dornbusch model, whereas in the Frankel model it overshoots by an amount

that is proportional to the expected real interest differential. In the long run (when s = ¯

s), the nominal interest differential will be equal to the inflation

differential (that is, ¯i − ¯i∗ = pe − p∗e), and therefore the expression

in brackets reduces to [(i − i∗) − ( ¯i − ¯

i∗)]. Intuitively, equation (6.3) can

be described as follows. When tight monetary policy causes the nominal

interest differential to rise above its long-run level, capital inflow causes the

domestic currency to rise above its equilibrium value proportionately to the

expected real interest differential.

6.2.2. A More General Model of Exchange Rate Determination

Frankel’s (1979b) real interest differential model is a more general model

that combines the features of the flexible-price and sticky-price models.

This model can be derived from equation (6.3) by identifying the determi-

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

nants of the long-run equilibrium exchange rate, which is determined by

equilibrium relative prices ( ¯ p − ¯

p∗). These are, in turn, determined by the

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

domestic and foreign equilibrium monetary conditions. Assuming money

market equilibrium and that the nominal interest differential is equal to the inflation differential ( ¯

i − ¯i∗ = pe − p∗e), the expected equilibrium rel-

ative prices can be expressed as a function of the relative money supply,

relative income, and the long-run expected inflation differential. Hence ( ¯ p − ¯ p∗) = ( ¯ m − ¯ m∗) − α( ¯ y − ¯ y∗) + β(p − p∗). (6.4)

Substituting equation (6.3) into (6.4), and assuming that the equilibrium

relative money supply and income are given by their current actual levels, 192

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates

we obtain a complete equation that represents the real interest differential model: 1 1

s = (m − m∗) − α(y − y∗) − (i − i∗) + + β (pe − p∗e). θ θ (6.5)

The real interest differential model is a general monetary model of exchange

rate determination because it allows for (i) the direct effect of the relative

money supply on the exchange rate as in all monetary models; (ii) the fic.com

indirect effect of expectations of higher or lower inflation as in the flexible-

price model; and (iii) the liquidity-induced effect of the money supply on

interest rates, capital flows, and hence on the exchange rate, as embodied in the sticky-price model.

By rearranging a number of terms on the right-hand side of

equation (6.5), we can also arrive at a specification showing that Frankel’s

real interest differential model is identical to the flexible-price monetary

model, except that the real interest differential is added as an explanatory variable: 1

s = (m − m∗) − α(y − y∗) + β(pe − p∗e) − [(i − pe) − (i∗ − p∗e)]. θ (6.6)

It can be shown that the real interest differential model includes both

the flexible- and the sticky-price monetary models as polar special cases.

To this end, equation (6.5) is rewritten as

s = (m − m∗) − α(y − y∗) + γ(i − i∗) + δ(pe − p∗e). (6.7)

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

The sticky-price model can be viewed as a special case of the real interest

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

differential model, as the latter reduces to the former when the coefficient on

the expected inflation differential in equation (6.7) is zero (that is, δ = 0).

The sticky-price model is empirically valid if the joint hypothesis δ = 0

and γ < 0 is not rejected. Likewise, the flexible-price monetary model is a

special case of the real interest differential model when the price adjustment

to equilibrium is instantaneous (that is, θ = ∞ in equation (6.5)) and when

real interest parity holds (that is, i − i∗ = pe − p∗e). The flexible-price

model turns out to be valid empirically if the joint hypothesis δ = 0 and γ > 0 is not rejected.

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 193

6.3. Driskell’s Generalized Stock-Flow Sticky-Price Model

Driskell (1981) argues that two striking implications follow from the

Dornbusch (1976c) model. First, in response to a change in relative money

supplies, the exchange rate may change immediately by more than the

long-run equilibrium value determined by purchasing power parity. In other

words, the exchange rate may overshoot its long-run purchasing power

parity value in the short run. Second, following this initial overshooting, the

exchange rate approaches monotonically its long-run equilibrium value. He

argues that both of these implications result from the key assumptions of fic.com

sticky prices and perfect capital mobility. Following the work of Branson

(1976), Niehans (1977), and Henderson (1980) (who have developed an

alternative view of exchange rate dynamics emphasizing stock-flow inter-

actions and relative-price trade-balance effects), Driskell (1981) developed

a generalized stock-flow variant of the Dornbusch model, leading to con-

trasting results of short-run undershooting and non-monotonic exchange

rate and price level adjustments.

Driskell (1981) generalizes the Dornbusch (1976c) overshooting model

to develop two structural models (what he calls the Dornbusch model in

discrete time and a stock-flow model) by allowing imperfect substitutability

between domestic and foreign assets. He argues that both of these structural

models impose a priori constraints on the reduced-form parameters and

thus can (in principle) be rejected by the data.

6.3.1. The Dornbusch Model in Discrete Time

To derive the Dornbusch model in discrete time, Driskell (1981) begins

with three basic building blocks: a money market equilibrium condition, a

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

price level adjustment equation, and the uncovered interest parity condition.

Assuming that the structural parameters of the domestic and foreign money

demand functions are identical and that the money supply (in both countries)

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

is exogenously controlled by the central bank, the money market equilibrium condition can be rewritten as

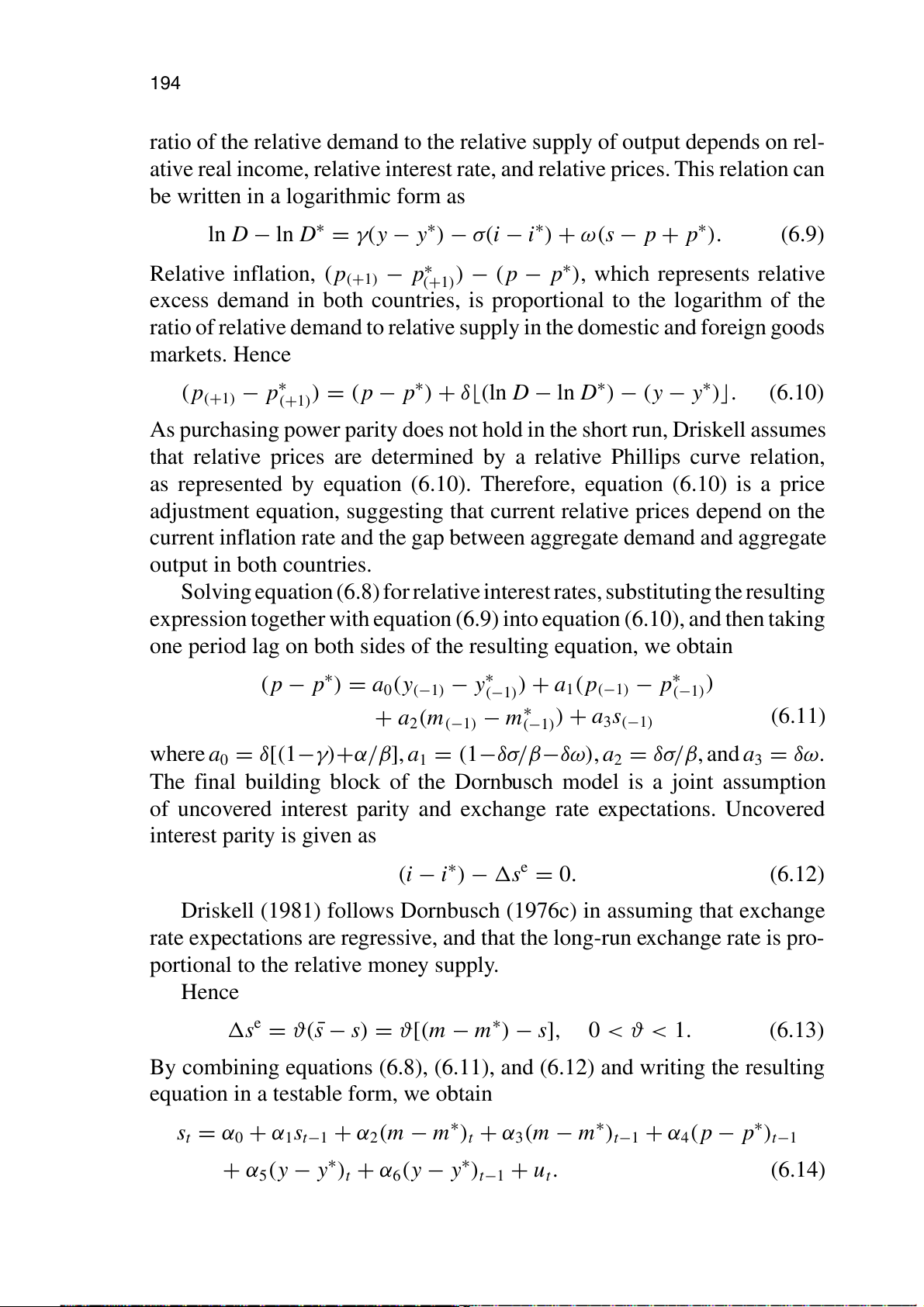

(m − m∗) = (p − p∗) + α(y − y∗) − β(i − i∗). (6.8)

Equilibrium is obtained in the (domestic and foreign) goods markets when

the demand for output is equal to the supply of output. Therefore, equi-

librium in the domestic and foreign goods markets can be specified in terms

of the logarithm of the ratio of relative demand to relative supply of output

in the two markets, which is a function of the relative inflation rate. The 194

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates

ratio of the relative demand to the relative supply of output depends on rel-

ative real income, relative interest rate, and relative prices. This relation can

be written in a logarithmic form as

ln D − ln D∗ = γ(y − y∗) − σ(i − i∗) + ω(s − p + p∗). (6.9)

Relative inflation, (p(+1) − p∗

) − (p − p∗), which represents relative (+1)

excess demand in both countries, is proportional to the logarithm of the

ratio of relative demand to relative supply in the domestic and foreign goods markets. Hence fic.com (p(+1) − p∗

) = (p − p∗) + δ(ln D − ln D∗) − (y − y∗). (6.10) (+1)

As purchasing power parity does not hold in the short run, Driskell assumes

that relative prices are determined by a relative Phillips curve relation,

as represented by equation (6.10). Therefore, equation (6.10) is a price

adjustment equation, suggesting that current relative prices depend on the

current inflation rate and the gap between aggregate demand and aggregate output in both countries.

Solving equation (6.8) for relative interest rates, substituting the resulting

expression together with equation (6.9) into equation (6.10), and then taking

one period lag on both sides of the resulting equation, we obtain

(p − p∗) = a0(y(−1) − y∗ ) + a ) (−1) 1(p(−1) − p∗ (−1) + a ∗ 2(m(−1) − m ) + a (−1) 3s(−1) (6.11)

where a0 = δ[(1−γ)+α/β], a1 = (1−δσ/β−δω), a2 = δσ/β, and a3 = δω.

The final building block of the Dornbusch model is a joint assumption

of uncovered interest parity and exchange rate expectations. Uncovered interest parity is given as (i − i∗) − se = 0. (6.12)

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

Driskell (1981) follows Dornbusch (1976c) in assuming that exchange

rate expectations are regressive, and that the long-run exchange rate is pro-

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

portional to the relative money supply. Hence se = ϑ( ¯

s − s) = ϑ[(m − m∗) − s], 0 < ϑ < 1. (6.13)

By combining equations (6.8), (6.11), and (6.12) and writing the resulting

equation in a testable form, we obtain s ∗

t = α0 + α1st−1 + α2(m − m∗)t + α3(m − m )t−1 + α4(p − p∗)t−1

+ α5(y − y∗)t + α6(y − y∗)t−1 + ut. (6.14)

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 195

The restrictions that Driskell (1981) imposes on the parameters are as

follows: α1 < 0, α2 > 1, α3 < 0, α4 < 0, α5 < 0, and α6 < 0. If α2 > 1,

then the hypothesis that the exchange rate overshoots in the short run cannot be rejected.

6.3.2. The Stock-Flow Model

Driskell (1981) developed a stock-flow model that generalizes the

Dornbusch model to allow for the possibility of imperfect capital mobility.

In this model, the demand for net capital flows (or foreign assets) is a linear fic.com

function of the expected net yield, which gives: F = κ[se − (i − i∗)] (6.15)

where κ > 0. The demand for net trade flows is determined by relative

prices and relative incomes, which gives

B = a(s − p + p∗) − b(y − y∗). (6.16)

The foreign exchange market clears when net capital flows are equal to net trade flows: F = B. (6.17)

Replacing equation (6.12) by (6.17) in the Dornbusch model and substi-

tuting (6.8) and (6.11) into (6.17), we obtain the following reduced-form exchange rate equation s ∗ ∗

t = β0 + β1st−1 + β2(m − m∗)t + β3(m − m )t−1 + β4(p − p )t−1

+ β5(y − y∗)t + β6(y − y∗)t−1 + vt (6.18)

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

where the parameters of the reduced-form equation (that is, the βi’s) must

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

satisfy the following constraints: 4 β β β i=1 i = 1, 1 < 1, 2 > 0, β3 = 0,

β4 > 0, β5 = 0, and β6 < 0. Like the reduced-form model represented

by equation (6.14), for purchasing power parity to hold in the long run the

sum of the estimates of all of the slope parameters must be equal to 1 (that is, 4 β i=1

i = 1). However, the other constraints imposed on the reduced-

form equation (6.18) are quite different. In particular, the coefficients on

lagged exchange rate and lagged price level coefficients (that is, β1 and β4)

may be positive. Also, note that the coefficient on the relative money supply

needs to be greater than 1. The model, therefore, implies that exchange rate

overshooting or undershooting is an empirical issue. 196

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates

Driskell’s model yields predictions that are clearly different from those

of the Dornbusch (1976c) and Frankel (1979b) models. The long-run

neutrality of money still holds but exchange rate overshooting is no longer

essential. With perfect substitutability between domestic and foreign assets,

α2 in the model represented by equation (6.14) would exceed one as a result

of exchange rate overshooting. With imperfect substitutability, however, the

initial response of the exchange rate to a monetary shock may be to over-

shoot or undershoot its long-run value. fic.com

6.4. The Equilibrium Real Exchange Rate Monetary Model

Hooper and Morton (1982) argue that the most serious deficiency of the

monetary model is that it neglects changes in external trade imbalances and

the impact these changes have on the exchange rate. The current account,

however, does not affect the exchange rate directly but only indirectly

through its impact on exchange rate expectations. Hooper and Morton

developed the equilibrium real exchange rate model that draws from mon-

etary and portfolio balance models. This model allows explicitly for the

short-run impact on the exchange rate of both the current account and

imperfect substitutability of assets.

The Hooper–Morton model is, in fact, an extension of the Dornbusch–

Frankel model that allows for large and sustained changes in real exchange

rates. The Dornbusch–Frankel model is modified to allow for shifts in

the long-run equilibrium real exchange rate and the existence of risk

premium. The Hooper–Morton model assumes that there is an equilibrium

real exchange rate that is expected to maintain current account equilibrium

in the long run. But at any point time, the equilibrium real exchange rate

is determined by the cumulative sum of past and present current account

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

balances. Thus, an unexpected permanent rise in the cumulative current

account surplus will require an upward adjustment in the equilibrium long-

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

run real exchange rate if the current account is to be eventually balanced.

This upward adjustment in the equilibrium long-run real exchange rate in

turn affects the equilibrium long-run nominal exchange rate through the

purchasing power parity channel.

6.4.1. The Expectation Mechanism and Exchange

Rate Determination

Hooper and Morton begin by arguing that unexpected changes in the current

account provide information about shifts in the underlying determinants that

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 197

make it necessary for offsetting shifts in the real exchange rate to maintain

current account equilibrium in the long run. An important point is that it

is only the unexpected component of the current account that affects the

exchange rate (the expected component is already taken into account by

the foreign exchange market). Therefore, the release by the government of

unexpected figures on the trade balance or current account appears to have

large immediate announcement effects on the exchange rate.

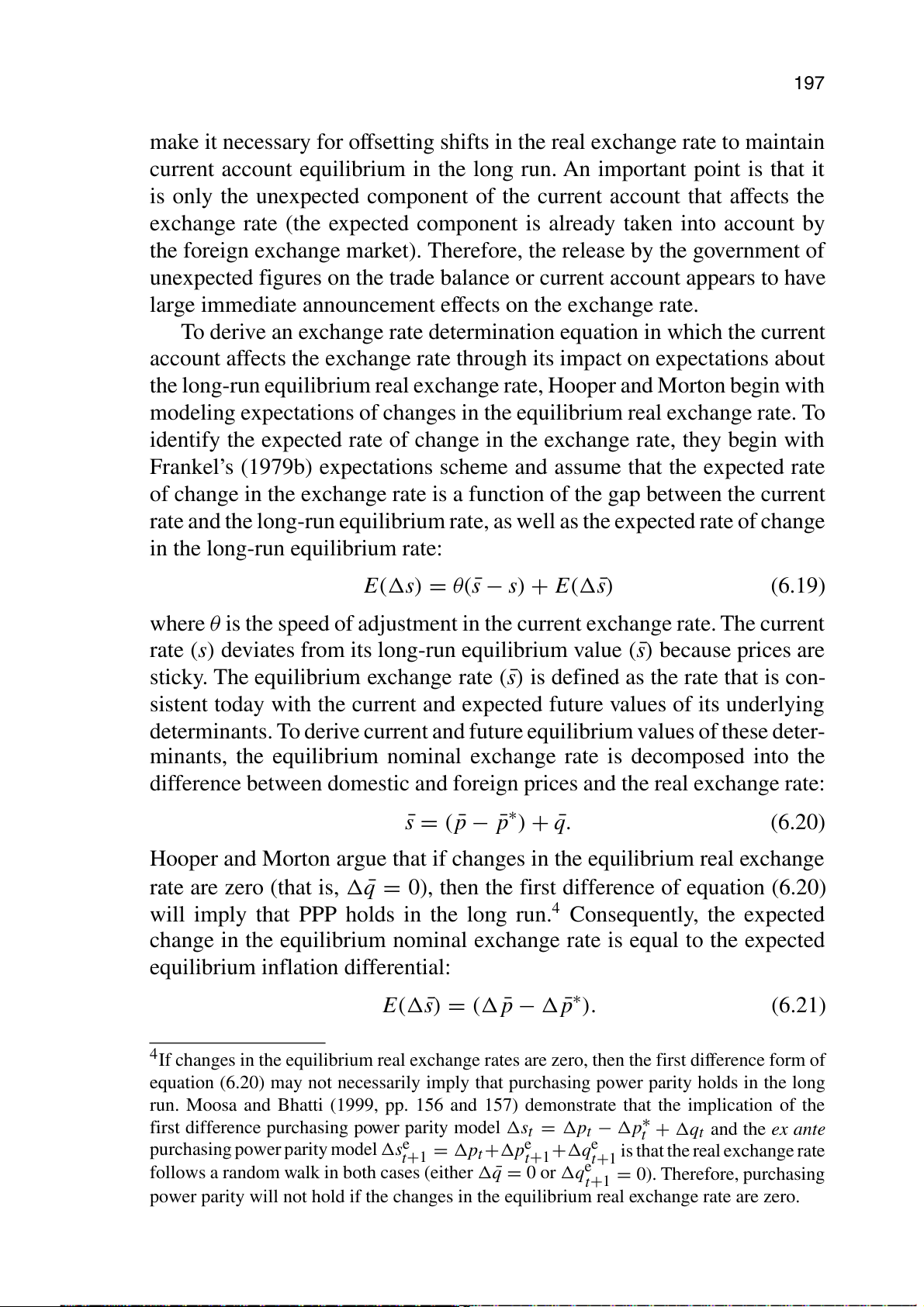

To derive an exchange rate determination equation in which the current

account affects the exchange rate through its impact on expectations about

the long-run equilibrium real exchange rate, Hooper and Morton begin with fic.com

modeling expectations of changes in the equilibrium real exchange rate. To

identify the expected rate of change in the exchange rate, they begin with

Frankel’s (1979b) expectations scheme and assume that the expected rate

of change in the exchange rate is a function of the gap between the current

rate and the long-run equilibrium rate, as well as the expected rate of change

in the long-run equilibrium rate: E(s) = θ( ¯ s − s) + E( ¯ s) (6.19)

where θ is the speed of adjustment in the current exchange rate. The current

rate (s) deviates from its long-run equilibrium value ( ¯ s) because prices are

sticky. The equilibrium exchange rate ( ¯

s) is defined as the rate that is con-

sistent today with the current and expected future values of its underlying

determinants. To derive current and future equilibrium values of these deter-

minants, the equilibrium nominal exchange rate is decomposed into the

difference between domestic and foreign prices and the real exchange rate: ¯s = ( ¯ p − ¯ p∗) + ¯ q. (6.20)

Hooper and Morton argue that if changes in the equilibrium real exchange rate are zero (that is, ¯

q = 0), then the first difference of equation (6.20)

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

will imply that PPP holds in the long run.4 Consequently, the expected

change in the equilibrium nominal exchange rate is equal to the expected

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

equilibrium inflation differential: E( ¯ s) = ( ¯ p − ¯ p∗). (6.21)

4If changes in the equilibrium real exchange rates are zero, then the first difference form of

equation (6.20) may not necessarily imply that purchasing power parity holds in the long

run. Moosa and Bhatti (1999, pp. 156 and 157) demonstrate that the implication of the

first difference purchasing power parity model s ∗

t = pt − pt + qt and the ex ante

purchasing power parity model se = p e t +p +qe t+1 t+1 is that the real exchange rate t+1

follows a random walk in both cases (either ¯ q = 0 or qe = 0). Therefore, purchasing t+1

power parity will not hold if the changes in the equilibrium real exchange rate are zero. 198

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates

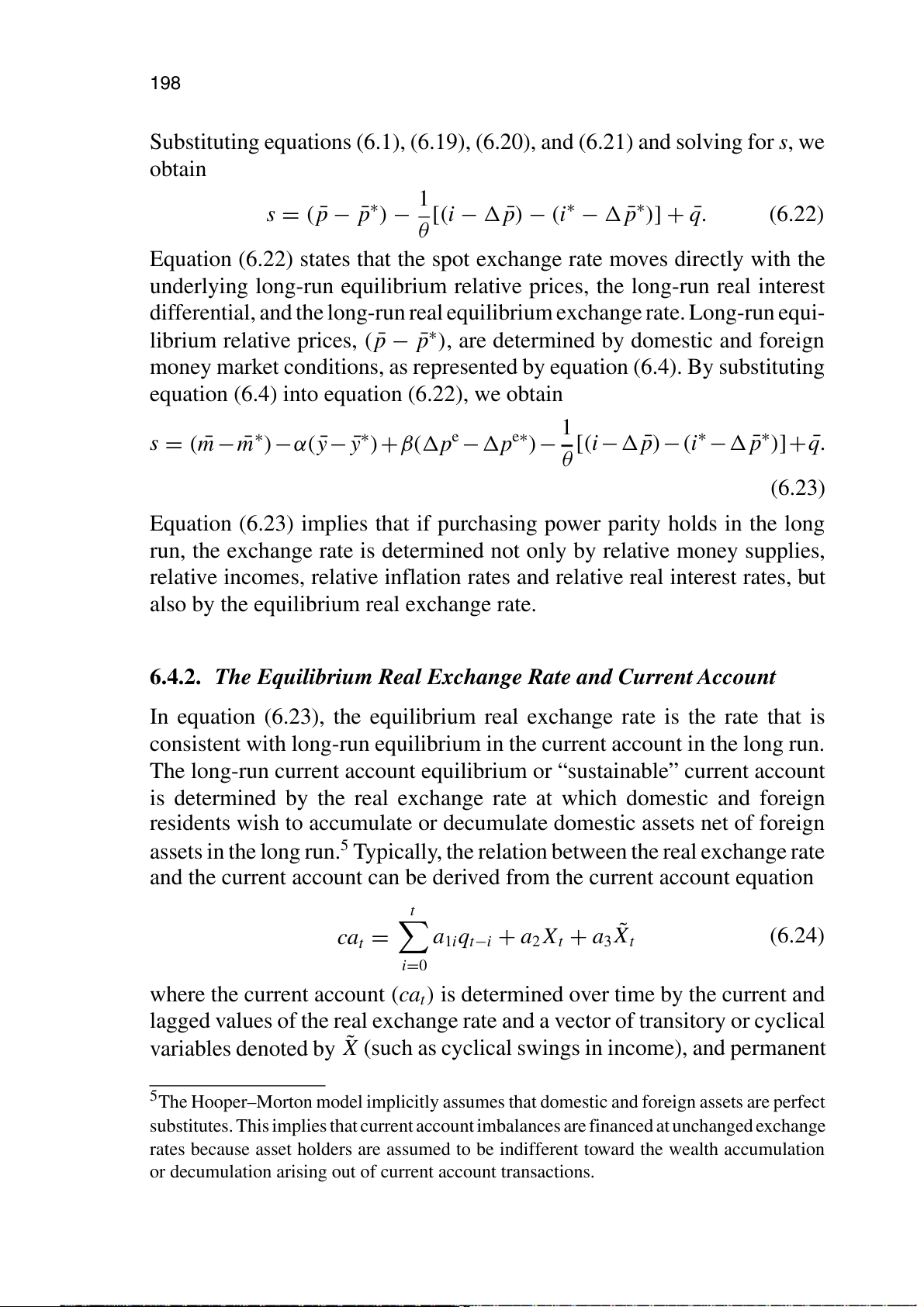

Substituting equations (6.1), (6.19), (6.20), and (6.21) and solving for s, we obtain 1 s = ( ¯ p − ¯ p∗) − [(i − ¯ p) − (i∗ − ¯ p∗)] + ¯ q. (6.22) θ

Equation (6.22) states that the spot exchange rate moves directly with the

underlying long-run equilibrium relative prices, the long-run real interest

differential, and the long-run real equilibrium exchange rate. Long-run equi- librium relative prices, ( ¯ p − ¯

p∗), are determined by domestic and foreign

money market conditions, as represented by equation (6.4). By substituting fic.com

equation (6.4) into equation (6.22), we obtain 1 s = ( ¯ m− ¯ m∗)−α( ¯ y − ¯

y∗)+β(pe −pe∗)− [(i− ¯ p)−(i∗ − ¯ p∗)]+ ¯ q. θ (6.23)

Equation (6.23) implies that if purchasing power parity holds in the long

run, the exchange rate is determined not only by relative money supplies,

relative incomes, relative inflation rates and relative real interest rates, but

also by the equilibrium real exchange rate.

6.4.2. The Equilibrium Real Exchange Rate and Current Account

In equation (6.23), the equilibrium real exchange rate is the rate that is

consistent with long-run equilibrium in the current account in the long run.

The long-run current account equilibrium or “sustainable” current account

is determined by the real exchange rate at which domestic and foreign

residents wish to accumulate or decumulate domestic assets net of foreign

assets in the long run.5 Typically, the relation between the real exchange rate

and the current account can be derived from the current account equation

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only. t ca ˜ t = a1iqt−i + a2Xt + a3Xt (6.24)

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti i=0

where the current account (cat) is determined over time by the current and

lagged values of the real exchange rate and a vector of transitory or cyclical variables denoted by ˜

X (such as cyclical swings in income), and permanent

5The Hooper–Morton model implicitly assumes that domestic and foreign assets are perfect

substitutes. This implies that current account imbalances are financed at unchanged exchange

rates because asset holders are assumed to be indifferent toward the wealth accumulation

or decumulation arising out of current account transactions.

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 199

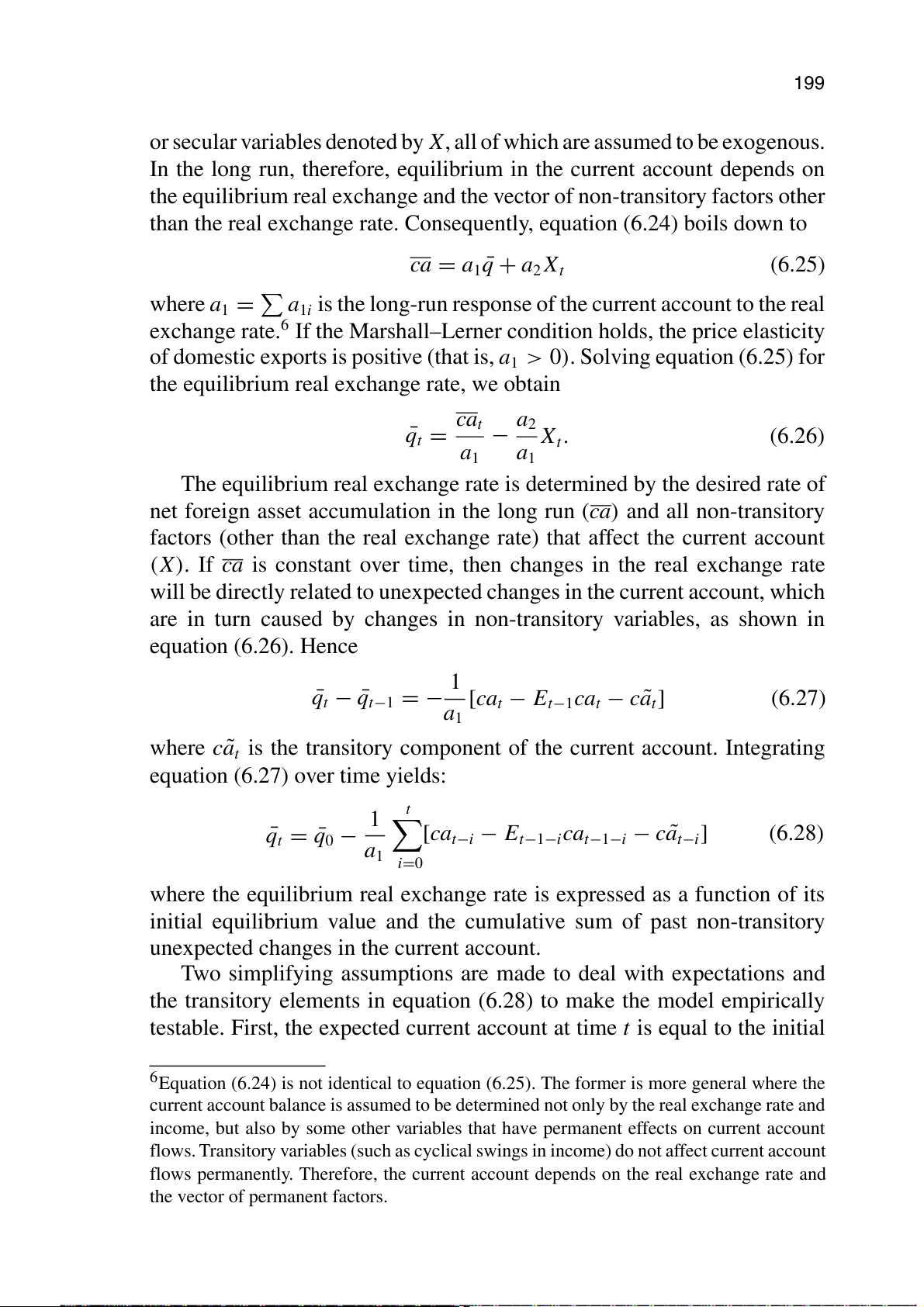

or secular variables denoted by X, all of which are assumed to be exogenous.

In the long run, therefore, equilibrium in the current account depends on

the equilibrium real exchange and the vector of non-transitory factors other

than the real exchange rate. Consequently, equation (6.24) boils down to ca = a1 ¯ q + a2Xt (6.25)

where a1 = a1i is the long-run response of the current account to the real

exchange rate.6 If the Marshall–Lerner condition holds, the price elasticity

of domestic exports is positive (that is, a1 > 0). Solving equation (6.25) for

the equilibrium real exchange rate, we obtain fic.com ca a ¯ t 2 qt = − Xt. (6.26) a1 a1

The equilibrium real exchange rate is determined by the desired rate of

net foreign asset accumulation in the long run (ca) and all non-transitory

factors (other than the real exchange rate) that affect the current account

(X). If ca is constant over time, then changes in the real exchange rate

will be directly related to unexpected changes in the current account, which

are in turn caused by changes in non-transitory variables, as shown in equation (6.26). Hence 1 ¯ qt − ¯ qt−1 = − [ca E c ˜ a a t − t−1cat − t ] (6.27) 1 where c ˜

at is the transitory component of the current account. Integrating

equation (6.27) over time yields: t 1 ¯ q [ t = ¯ q0 −

cat−i − Et−1−icat−1−i − c ˜ at−i] (6.28) a1 i=0

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

where the equilibrium real exchange rate is expressed as a function of its

initial equilibrium value and the cumulative sum of past non-transitory

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

unexpected changes in the current account.

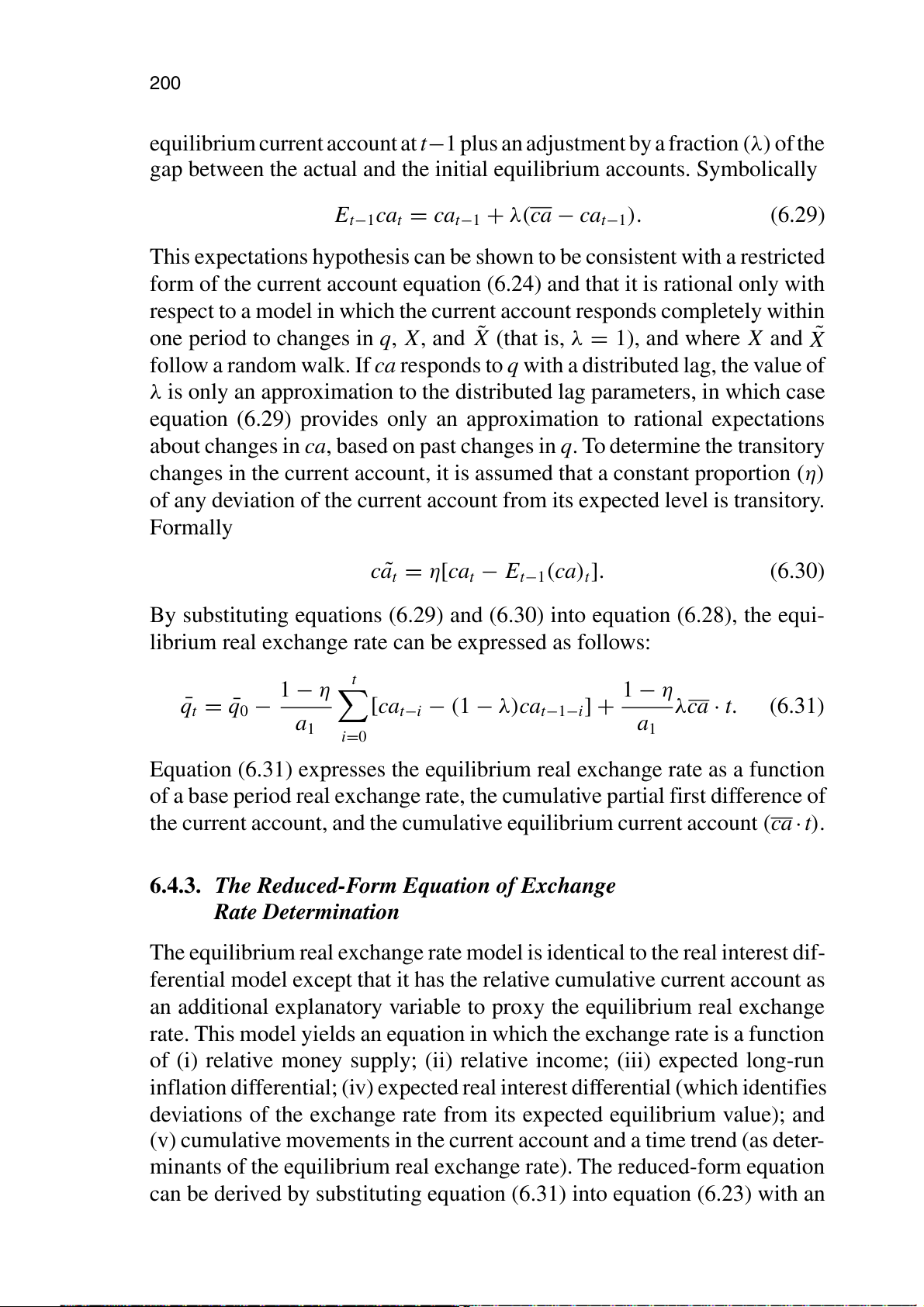

Two simplifying assumptions are made to deal with expectations and

the transitory elements in equation (6.28) to make the model empirically

testable. First, the expected current account at time t is equal to the initial

6Equation (6.24) is not identical to equation (6.25). The former is more general where the

current account balance is assumed to be determined not only by the real exchange rate and

income, but also by some other variables that have permanent effects on current account

flows. Transitory variables (such as cyclical swings in income) do not affect current account

flows permanently. Therefore, the current account depends on the real exchange rate and

the vector of permanent factors. 200

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates

equilibrium current account at t−1 plus an adjustment by a fraction (λ) of the

gap between the actual and the initial equilibrium accounts. Symbolically

Et−1cat = cat−1 + λ(ca − cat−1). (6.29)

This expectations hypothesis can be shown to be consistent with a restricted

form of the current account equation (6.24) and that it is rational only with

respect to a model in which the current account responds completely within

one period to changes in q, X, and ˜

X (that is, λ = 1), and where X and ˜ X

follow a random walk. If ca responds to q with a distributed lag, the value of fic.com

λ is only an approximation to the distributed lag parameters, in which case

equation (6.29) provides only an approximation to rational expectations

about changes in ca, based on past changes in q. To determine the transitory

changes in the current account, it is assumed that a constant proportion (η)

of any deviation of the current account from its expected level is transitory. Formally c ˜ at = η[cat − Et−1(ca)t]. (6.30)

By substituting equations (6.29) and (6.30) into equation (6.28), the equi-

librium real exchange rate can be expressed as follows: t 1 − η 1 − η ¯ qt = ¯ q0 −

[cat−i − (1 − λ)cat−1−i] + λca · t. (6.31) a1 a1 i=0

Equation (6.31) expresses the equilibrium real exchange rate as a function

of a base period real exchange rate, the cumulative partial first difference of

the current account, and the cumulative equilibrium current account (ca · t).

6.4.3. The Reduced-Form Equation of Exchange

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

Rate Determination

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

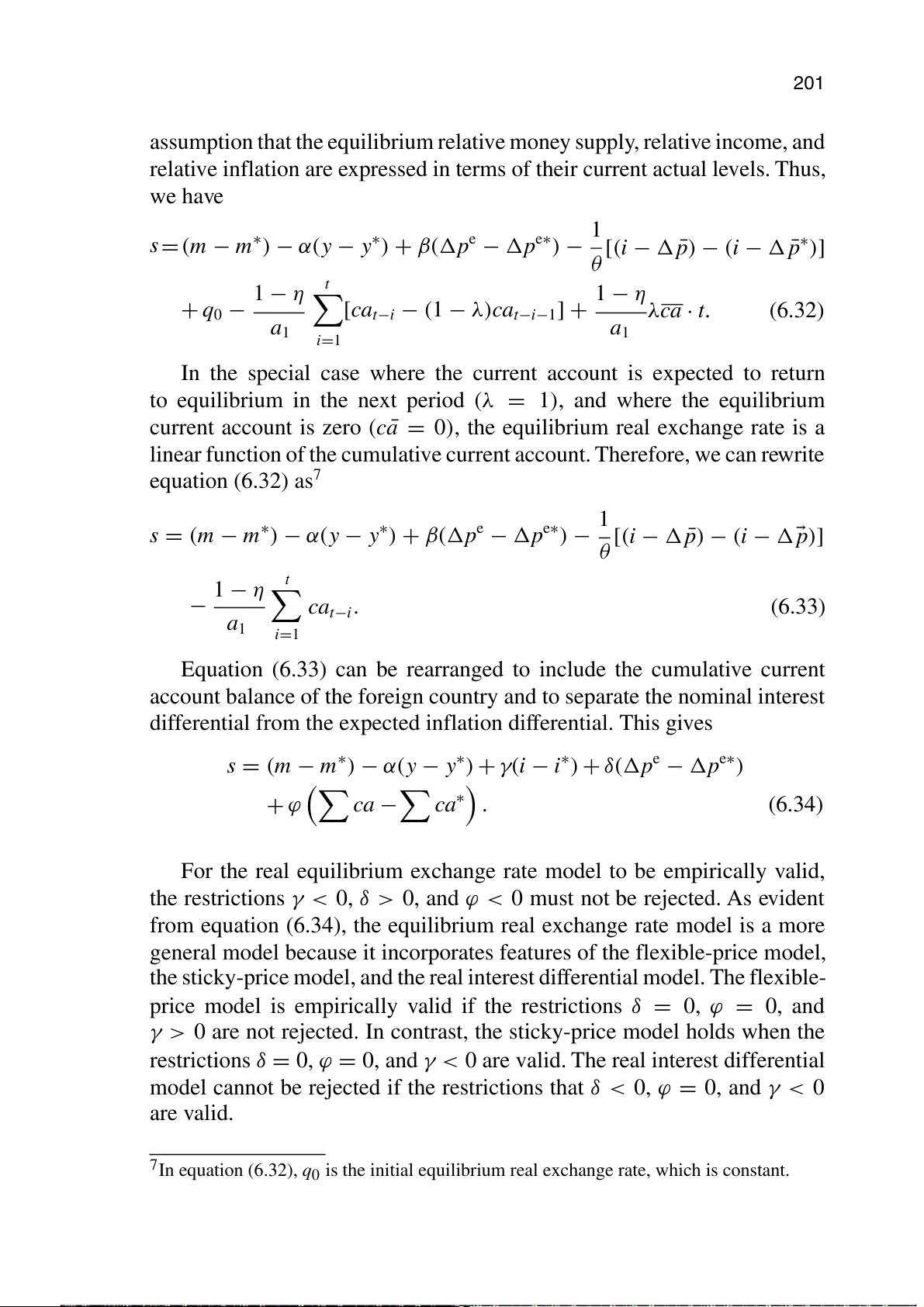

The equilibrium real exchange rate model is identical to the real interest dif-

ferential model except that it has the relative cumulative current account as

an additional explanatory variable to proxy the equilibrium real exchange

rate. This model yields an equation in which the exchange rate is a function

of (i) relative money supply; (ii) relative income; (iii) expected long-run

inflation differential; (iv) expected real interest differential (which identifies

deviations of the exchange rate from its expected equilibrium value); and

(v) cumulative movements in the current account and a time trend (as deter-

minants of the equilibrium real exchange rate). The reduced-form equation

can be derived by substituting equation (6.31) into equation (6.23) with an

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 201

assumption that the equilibrium relative money supply, relative income, and

relative inflation are expressed in terms of their current actual levels. Thus, we have 1

s = (m − m∗) − α(y − y∗) + β(pe − pe∗) − [(i − ¯ p) − (i − ¯ p∗)] θ t 1 − η 1 − η + q0 −

[cat−i − (1 − λ)cat−i−1] + λca · t. (6.32) a1 a1 i=1

In the special case where the current account is expected to return fic.com

to equilibrium in the next period (λ = 1), and where the equilibrium current account is zero (c ¯

a = 0), the equilibrium real exchange rate is a

linear function of the cumulative current account. Therefore, we can rewrite equation (6.32) as7 1

s = (m − m∗) − α(y − y∗) + β(pe − pe∗) − [(i − ¯ p) − (i − p)] θ t 1 − η − cat−i. (6.33) a1 i=1

Equation (6.33) can be rearranged to include the cumulative current

account balance of the foreign country and to separate the nominal interest

differential from the expected inflation differential. This gives

s = (m − m∗) − α(y − y∗) + γ(i − i∗) + δ(pe − pe∗) + ϕ ca − ca∗ . (6.34)

For the real equilibrium exchange rate model to be empirically valid,

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

the restrictions γ < 0, δ > 0, and ϕ < 0 must not be rejected. As evident

from equation (6.34), the equilibrium real exchange rate model is a more

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

general model because it incorporates features of the flexible-price model,

the sticky-price model, and the real interest differential model. The flexible-

price model is empirically valid if the restrictions δ = 0, ϕ = 0, and

γ > 0 are not rejected. In contrast, the sticky-price model holds when the

restrictions δ = 0, ϕ = 0, and γ < 0 are valid. The real interest differential

model cannot be rejected if the restrictions that δ < 0, ϕ = 0, and γ < 0 are valid.

7In equation (6.32), q0 is the initial equilibrium real exchange rate, which is constant. 202

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates

6.4.4. The Impact of the Risk Premium on the Exchange Rate

Portfolio preferences influence the exchange rate to the extent that they

play a role in the determination of the equilibrium real exchange rate (by

identifying the long-run current account). Now, we relax this assumption

and allow for imperfect substitutability of assets in the short run and the

existence of a risk premium, which gives E(s) = i − i∗ − ρ (6.35)

where ρ is the risk premium that asset holders demand on domestic assets fic.com

relative to foreign assets, given wealth, asset stocks, and the expected rel-

ative rates of return on those assets. Hooper and Morton (1982) employed

an abbreviated specification, expressing the risk premium as a linear

function of the cumulative current account, intervention flows, and an initial condition: T ρ = φ0 − φ1 (ca−j + I−j) (6.36) j=2

By allowing for the risk premium in equation (6.22), we obtain 1 ρ s = ¯ s − [(i − ¯ p) − (i∗ − ¯ p∗)] + ¯ q + . (6.37) θ θ

Substituting equations (6.37) and (6.31) into equation (6.23), we obtain s = ( ¯ m − ¯ m∗) − α( ¯ y − ¯ y∗) + β(pe − pe∗) 1 − [(i − ¯ p) − (i∗ − ¯ p∗)] + ¯ q0 θ t 1 − η

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only. − [ca a

t−i − (1 − λ)cat−i−1] 1 i=1 T

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti 1 − η φ φ + 0 1 λca · t + − (ca−j + I−j). (6.38) a1 θ θ j=1

In equation (6.38), the current account affects the exchange rate via two

channels: expectations and short-run portfolio rebalancing. In the former

case, the announcement of a current account deficit (that is, unexpected and

nontransitory) affects the exchange rate (through changes in expectations

about the equilibrium exchange rate) in such a way as to restore long-

run equilibrium or a “sustainable” current account. In the latter case, if

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 203

the current account deficit is not financed by official intervention during

the length of time it takes to return to equilibrium, the necessary private

financing is attracted with an increase in the risk premium, which causes

the real exchange rate to overshoot its expected equilibrium level.

6.5. The Buiter–Miller Model with Core Inflation Rate

Buiter and Miller (1981) developed a variant of the Dornbusch (1976c)

sticky-price model that incorporates a core inflation rate, which is used to fic.com

analyze the dynamic effects of natural resource discoveries on output and

the exchange rate. Their analysis is designed to be suggestive of the U.K.’s

experience with the discovery of oil in the North Sea in the 1970s.

Buiter and Miller begin by specifying a money market equilibrium con-

dition, and a rational expectations augmented version of the UIP condition.

These two relations are written as mt − pt = φyt − λit (6.39) st+1 = (it − i∗). (6.40) t

In equation (6.40), the actual change in the exchange rate appears instead

of the expected change, reflecting the assumption of rational expectations.

The aggregate demand function explicitly incorporates the (negative) effect

of the real interest rate. Hence dt = α( ˙ pt − it) + β(st − pt). (6.41)

Inflation is assumed to be proportional to the level of excess demand over

the full employment level of output plus a core inflation rate:

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only. ˙ pt = (dt − yt) + µt. (6.42)

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

The core inflation rate (µ) is equal to the rate of growth in the money supply: µt = ˙ mt (6.43)

In the sticky-price monetary model, long-run equilibrium is achieved when

the current and long-run exchange rates are equal. In the Buiter–Miller

model, however, the presence of a core inflation rate implies a nonzero

difference between the current exchange rate and the long-run rate. This 204

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates

result arises because, in equilibrium, the nominal interest rate is equal to

the real interest rate plus the core inflation rate through the Fisher effect: rt = it + µt. (6.44)

By combining equations (6.39)–(6.44), the following expression is derived 1 α s − + t = mt + φ yt + λ it + λµt (6.45) β β

which tells us that the exchange rate is determined by income, interest rate, fic.com and the core inflation rate.

6.6. Frankel’s Sticky-Price Model with a Wealth Effect

Frankel (1982a) developed an alternative version of the real interest differ-

ential model that takes into account the wealth effect. To derive this model,

the money market condition represented by equation (6.4) is modified by

incorporating into the domestic and foreign money demand functions rel-

ative wealth level as an additional explanatory variable. Formally, we have ( ¯ p − ¯ p∗) = ( ¯ m − ¯ m∗) − α( ¯ y − ¯

y∗) + β(p − p∗) − φ(w − w∗). (6.46)

By substituting equation (6.46) into equation (6.3), we obtain 1 1

s = (m−m∗)−α(y−y∗)−φ(w−w∗)− (i−i∗)+ + β (pe −p∗e). θ θ (6.47)

Notice that the coefficients on relative income, relative wealth, and relative

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

interest rate are negative, whereas those on relative money supplies and

relative inflation rates are positive. Thus, an increase in domestic wealth

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti

relative to foreign wealth (caused by a surplus in the current account of the

home country) leads to appreciation of the domestic currency because of

the increase in the demand for domestic money relative to foreign money.

Similarly, given the expected inflation rate, if the domestic interest rate

is higher than the foreign rate, there is an incipient capital inflow that

causes the domestic currency to appreciate. Frankel tested this model for

the mark/dollar exchange rate over the period 1974–80 and found results

that were supportive of the real interest differential model with wealth as

an additional explanatory variable.

Other Sticky-Price Monetary Models of Exchange Rates 205 6.7. Recapitulation

The sticky-price monetary model of Dornbusch allows substantial short-

term overshooting of nominal and real exchange rates beyond the long-

run equilibrium values determined by purchasing power parity because the

“jump variables” in the system (exchange rates and interest rates) com-

pensate for sluggishness in other variables, notably goods prices. This model

is a representation of long-run equilibrium toward which the economy tends

to adjust, while in the short run it is possible for the exchange rate to over- shoot its long-run value. fic.com

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, a wide range of sticky-price

models were developed to account for some observations pertaining to the

behavior of flexible exchange rates. These models include the real interest

differential model of Frankel (1979b), the stock-flow model of Driskell

(1981), and the equilibrium real exchange rate sticky-price model of Hooper

and Morton (1982). While these models appeared to have made some useful

additions to the Dornbusch model, their empirical validity remained as

questionable as their predecessors.

by UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE on 01/13/17. For personal use only.

The Theory and Empirics of Exchange Rates Downloaded from www.worldscienti