Preview text:

World Review of Intermodal Transporta tion Research, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2020 27

The impact of logistics performance on exports,

imports and foreign direct investment

Sandra Luttermann* and Herbert Kotzab

Chair of General Business and Logistics Management, University of Bremen,

Max-von-Laue-Straße 1, 28359 Bremen, Germany

Email: luttermann@uni-bremen.de Email: kotzab@uni-bremen.de *Corresponding author Tilo Halaszovich

Department of Business and Economics, Jacobs University Bremen,

Campus Ring 1, 28759 Bremen, Germany

Email: t.halaszovich@jacobs-university.de

Abstract: Logistics performance (LP) is strongly connected to trade and

investment, and gains growing importance in describing the competitiveness of

countries. Increasing world trade simultaneously requires continuous progress

in logistics or transport technologies so that the performance of logistics

infrastructure becomes a necessary condition for foreign investors to operate

efficiently. The aim of this paper is to examine how LP contributes to trade and

foreign direct investment (FDI). This question has been empirically analysed

by performing a panel data analysis using secondary data on 20 Asian

countries. Our results prove a statistically significant relationship between LP

and trade as well as FDI. So far, LP is rarely considered in explaining the

attractiveness of countries as trading partners or as an investment target. The

paper fills the gap in the literature by analysing the relationship between LP and trade as well as FDI.

Keywords: logistics performance; foreign direct investment; FDI; international

trade; export; import; country competitiveness; developing countries;

infrastructure; transport; gretl; panel data analysis.

Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Luttermann, S., Kotzab, H.

and Halaszovich, T. (2020) ‘The impact of logistics performance on exports,

imports and foreign direct investment’, World Review of Intermodal

Transportation Research, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp.27–46.

Biographical notes: Sandra Luttermann has been working as a doctoral

candidate at the Chair of Logistics Management at the University of Bremen

since 2017. Her field of research covers the measurement of logistics

performance from a macroeconomic perspective and the influencing factors of

foreign direct investment. Her dissertation will be entitled ‘The influence of

logistics performance on foreign direct investment’. She received her Master’s

degree from the University of Bremen in 2016 and is expected to complete her dissertation in 2020.

Copyright © 2020 Inderscience Enterprises Ltd. 28 S. Lutterman n et al.

Herbert Kotzab is a Professor at the Chair of Logistics Management at the

University of Bremen and International Professor at Othman Yeop Abdullah

Graduate School of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia. He received

his Master of Business Administration in Marketing and Management, PhD

(1996) and Postdoctoral degree (Habilitation; 2002) from the Vienna

University of Economics and Business Administration. Prior to his assignment

at Bremen, he held a Professor position at Copenhagen Business School at the

Department of Operations Management. His research focuses on Supply Chain

Management, Service Operations and Consumer Driven Value Networks. Since

2013, he has been a member of the Editor-in-Chief-Board of Logistics Research.

Tilo Halaszovich is a Professor of Global Markets and Firms at Jacobs

University Bremen. He graduated from the RWTH Aachen with a degree in

Business Studies (2006) and received a PhD in Marketing from the University

of Bremen (2010). His research is mostly focused on quantitative analysis in

International Business and Marketing. He is especially interested in the

competitiveness of foreign and domestic firms in Developing Countries. He

serves as communications officer on the board of the European International

Business Academy (EIBA) and is the founder and chairperson of the

EIBA-Early Career Network (EIBA’s young fellow organisation).

This paper is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled ‘The impact of

logistics on international trade and investment flows’ presented at Nofoma 2017, Lund, 8 June 2017. 1 Introduction

Both international trade and investment flows have continued to increase sharply in

recent years. This development poses significant challenges, particularly in the field of

logistics, and is inextricably linked to global trade and cross-border fragmentation of

production processes. Logistics is thereby not only challenged in a special way, but also

represents the necessary prerequisites and the driver for international trade and global

operations (Shepherd, 2013; Verhetsel et al., 2015). Straube et al. (2008) furthermore

argue that technological advances in transport and communication systems and the

removal of trade barriers are regarded as the most important drivers that may have led to

the expansion of international trade. Since the production of various products and

intermediate goods takes place in many different countries, the quality of physical

infrastructures is an important prerequisite for a country when participating in global

value chains or production networks. The outsourcing of production to countries with

poor transport infrastructure can be viewed critically if it cannot be guaranteed that

produced goods will reach international markets on time (Shepherd, 2013).

Efficient logistics facilitate the transportation of goods, ensure their safety and speed

and provide cost reductions when trading among countries. If a country has an inefficient

logistics performance (LP), this will result in higher costs in terms of time and money and

thereby affects a company’s performance and may also isolate a country from world

markets (Martí et al., 2014). Logistics connect companies to domestic and international

markets through reliable supply chain networks. These supply chains are complex and

their performance is largely dependent on country characteristics such as infrastructure.

The impact of logistics performance on exports, imports and FDI 29

Therefore Arvis et al. (2018) recognise LP as one of the most important indicators of a

country’s competitiveness. Due to this interrelationship between logistics, trade and

investment, we assume that the country’s LP operates as location advantage and thereby

helps to attract foreign direct investments (FDIs) from abroad.

The aim of this work is to analyse this relationship more deeply and to examine the

influence of LP on trade and investment. Our findings provide recommendations for

governmental decision makers to take action as we identify those areas which help

countries to better participate in international trade and become a more attractive

outsourcing location for foreign companies’ production facilities. Both can help countries

achieve a range of social and economic goals (see Section 2.3).

There are already studies that examine the influence of LP on economic growth

(D’Aleo and Sergi, 2017; Khan et al., 2017; Millán et al., 2013). Using the logistics

performance index (LPI), Millán et al. (2013) have found, for example, that an increase in

LP positively affects world economic growth. On the other hand, investigations as to

whether LP can explain the attractiveness of a country as a trading partner or as an

investment target have hardly been considered in research to date. Therefore, this article

offers an extension of classical research approaches on the factors influencing trade and

investment from a logistical perspective. Previous studies examine trade and investment

flows from a more exclusive and separate perspective (see Section 2.2.). However, as

these elements are directly related (Duval et al., 2008), it seems sensible to consider a

joint analysis. Furthermore, a macroeconomic view of logistics is underrepresented in the

literature. Many studies of LP focus on the factors that take place at a company level (see

Section 2.1.). Therefore, our approach offers an additional perspective on the topic of LP.

Finally, it should be noted that most studies rely exclusively on LPI data from the World

Bank to map LP. However, this restricts the analyses to just a few years. Our approach

also includes data from the World Economic Forum to describe LP so that it is possible to

study a longer period of time than just the years provided by the LPI (Arvis et al., 2018).

For the purpose of our research, LP is based on the LPI and the global

competitiveness index (GCI). The basic hypothesis of this paper states that good LP

positively affects FDI as well as the export and import volume of a country. A panel data

analysis will be carried out, covering 20 Asian countries over a period of 12 years

(2006–2017). We selected Asia as a research unit because the World Investment Report

highlights this region as the largest FDI recipient region in 2017 (UNCTAD, 2018).

There are also a large number of developing countries in this region which appear to be

of fundamental interest for such a study (see Section 2.3.).

After presenting the background of our research problem, research question and basic

hypothesis, we discuss our theoretical foundation in the second part of this article. This

includes a macro-economic perspective on logistics, an overview of studies on the link

between logistics, international trade and investment flows, as well as the role of

international trade and FDI for developing countries. These are the pillars of our

conceptual framework. Section 3 includes a thorough description of our methodological

approach in regards to data collection as well as data analysis. Section 4 shows the results

of our empirical analysis including a discussion of our hypotheses testing. The paper

concludes with a critical summary of our findings, implications and limitations as well as

an outlook for future research. 30 S. Lutterman n et al. 2 Theoretical background

2.1 The logistics concept from a macroeconomic perspective

Since research on the performance of logistics systems considers LP predominantly on

the micro-level of the firm (Bowersox and Closs, 2011; Chopra and Meindl, 2013;

Gudehus and Kotzab, 2012), a definition for a country’s LP must first be made. Inspired

by Alam and Bagchi (2011), we define LP in this work as the ability of countries to meet

the needs of multinational companies in a supply chain and to ensure a timely and

efficient distribution of their products, thus enabling them to participate in international trade.

The LPI is provided by the World Bank and measures the LP of more than

160 countries. It shows the ‘logistics friendliness’ of countries and identifies possibilities

and challenges for logistics in the analysed countries. The LPI includes six different

variables, which are defined as follows (Arvis et al., 2018):

1 customs: efficiency of customs and border management clearance

2 infrastructure: quality of trade and transport infrastructure

3 ease of arranging shi p ments: ease of arranging competitively priced shipments

4 quality of logistics service: competence and quality of logistics services – trucking,

forwarding, and customs brokerage of logistics services

5 tracking and traci n g: ability to track and trace consignments

6 timeliness: frequency with which shipments reach consignees within scheduled or expected delivery times.

In addition to the soft data from the LPI, Memedovic et al. (2008) propose the

hard-data-based logistics capability index (LOCAI), which is a composite index

consisting of the following five variables(Memedovic et al., 2008): quality of logistics

services, modern infrastructure, traditional infrastructure adapted to multimodal

transportation, trade facilitation and soft infrastructure. Depending on its level, the

LOCAI indicates how likely it is that a country will be able to participate in global value

chains (Memedovic et al., 2008).

In contrast to the LPI, the LOCAI is more precise when it comes to the term

infrastructure as it differs between a physical and information infrastructure which is also

supported by other authors (Lu et al., 2010; Memedovic et al., 2008).

• Physical infrastructure is determined by the transport systems of a region, an

economy or the world economy. These include individual transport modes, such as

roads, railways, airports and water, and also interchanges and switching yards. The

physical infrastructure provides greater supply possibilities through continuous

vehicle movements and enables long distances to be bridged geographically and

borders to be crossed (Alam and Bagchi, 2011; Bagchi, 2001; Memedovic et al., 2008).

The impact of logistics performance on exports, imports and FDI 31

• Information infrastructure is associated with information and communication

technologies (ICT). ICT allow companies to transfer information over long distances

in fast, cheap and reliable ways (Blyde and Molina, 2015; Memedovic et al., 2008).

Information provides decision-relevant data to plan and implement logistical

processes. They are the prerequisite of IT related logistics and have considerable

potential to increase efficiency along the logistics processing chain (Hausladen, 2016).

Another LP-model was developed by Wong and Tang (2018). Their index is based on the

resource-based view and institutional theory, and includes six factors: corruption,

political stability, labour market, infrastructure, technology and education. The level of

the regulatory environment is given much greater importance here. The whole business

environment is characterised by institutions. These include parliaments, implementers

and enforcers of rules and regulations (e.g., public services, police, law enforcement

agencies), financial institutions and educational institutions such as universities, colleges

and schools (North, 1991). The quality of LP is influenced by particular market

regulations. Supply chains are dependent on institutions, transport and custom laws,

regulations on trade facilitation and standards in packaging and labelling (Arvis et al.,

2016). Institutional quality is expected to facilitate or decrease LP; countries with low

levels of corruption and a stable political environment are likely to lead to a high level of LP (Wong and Tang, 2018).

Furthermore, other approaches explicitly list the supply environment (the

environment in which suppliers operate) as an important factor for LP (Alam and Bagchi,

2011; Arvis et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2010; Memedovic et al., 2008). The supply

environment can include the general offers of local suppliers and logistics service

providers as well as logistics clusters such as freight centres. Because more organisations

focus on their core competencies, it is important to have possibilities for the outsourcing

of other tasks such as warehousing or transport. Hereby supplier networks become a

source of competitive advantage (Alam and Bagchi, 2011; Arvis et al., 2016; Memedovic et al., 2008).

At this stage we are able to see that the identified models present mainly theoretical

constructs. Only the LPI offers data to measure LP, which is why it has established itself

in the literature as a common indicator for mapping the LP of countries (Arvis et al.,

2018; Martí et al., 2017; Ojala and Rantasila, 2012; Önsel Ekici et al., 2016). Therefore,

we also use the LPI in our approach to justify the availability of data.

2.2 Studies on the link between logistics, international trade and investment flows

It seems that research in this field does not have a long tradition. An early attempt was

conducted by Khadaroo and Seetanah (2009) who analysed the impact of transport

infrastructure on FDI through a panel data analysis. The study focused on twenty African

countries and reviewed data from 1986 to 2000. The fixed effect model shows a positive

and significant impact for transport infrastructure on FDI. 32 S. Lutterman n et al.

Martí et al. (2014) examined the influence of LPI variables on international trade in

emerging markets for the years 2007 and 2012 by using a gravity model. Overall, the

impact of LP is more important for exports than for imports. All LPI categories have a

statistically significant impact, but the most important categories are ‘infrastructure’,

‘timeliness’ and ‘customs’.

Shah (2014) studied the influence of infrastructure on FDI flows to developing

countries through a panel of 90 developing countries over the period of 27 years

(1980–2007). A positive statistical effect of the ICT infrastructure on FDI was found, but

another infrastructure proxy (gross fixed capital formation) was not statistically significant.

Blyde and Molina (2015) analysed the influence of logistics infrastructure on vertical

FDI with a gravity equation. They found that logistics infrastructure had a positive and

statistically significant influence on vertical FDI. The logistical infrastructure consists of

three components: the quality of ports, airports and an index for the ICT infrastructure of the countries surveyed.

Lately, Gani (2017) investigated the influence of LP on exports and imports and

found a statistically significant influence. LPI data from four years was used to map the

LP and export and import data, to map international trade. Regression analysis shows that

all individual LPI categories have a statistically significant influence on exports, whereas

only ‘customs’ and ‘ease of arranging shipments’ have an impact on imports.

Taking the findings of these studies together, it becomes clear that so far, trade and

investments flows have only been analysed separately. This separation is surprising as

integration in global value chains includes both FDI and trade. Moreover, it is noteworthy

that most studies rely exclusively on LPI data from the World Bank to map LP. Contrary

to this, we are also going to use data from the World Economic Forum in order to

describe LP which allows us to examine a longer period of time than just the years

provided by the World Bank. Next, we will develop our argument on the need of

developing countries to improve their attractiveness for trade and FDI in order to realise economic growth effects.

2.3 On the role of international trade and FDI for developing countries

A major characteristic of developing countries is their disadvantageous position when it

comes to their participation in global market activities. While the pace of global

integration continues to escalate, developing countries are increasingly competing in

terms of their capabilities to become linked to global as well as regional markets in an

efficient way (DiCaprio et al., 2017). Trade and transport infrastructure remain a serious

constraint in many developing countries. Many countries require significant investments

in basic infrastructure such as ports, airports, roads, and rail links (Shams, 2003). Also,

red tape and governance still remain serious issues facing importers and exporters in

many developing countries. It is the quality of infrastructure as well as institutional

frameworks which exclude countries from world trade as they are not able to integrate

with global production networks (Shepherd, 2013).

There is a wide range of literature dealing with the impact of international trade and

FDI on participating countries. Both FDI and international trade, under appropriate

conditions, influence a country’s development by encouraging it to achieve economic

and social goals (Dadush et al., 2015; Dunning and Lundan, 2008; Novik and de Crombrugghe, 2018).

The impact of logistics performance on exports, imports and FDI 33

International trade improves economic growth by allowing countries to participate in

global market activities and also permits access to other products and services (Makki

and Somwaru, 2004). Countries with an open trade policy tend to grow economically

faster than countries with restrictive barriers to world market participation. In addition,

international trade contributes to the improvement of the living standards of people all

over the world. This is also achieved by efficient transport and logistics activities as

important goods can be moved more quickly and more efficiently. This also applies for

basic products such as food or pharmaceuticals. Efficiency improvements in the transport

sector (by lowering transport costs) allow the supply of food and medicine for all society

classes thus improving the wealth of the nations (Shepherd, 2013).

Companies face increased competition when competing in global markets and as

such, they need to be more innovative to improve the quality and competitiveness of their

products (Dunning and Lundan, 2008). FDI is one of the most important ways to transfer

advanced technologies to developing countries (Makki and Somwaru, 2004).

Multinational companies impact the technological capacity of a country positively as

research and development activities can be undertaken at lower costs in developing

countries. However, through these activities this knowledge is also transferred to these

countries, which would not be available otherwise (Blomström et al., 2001).

With sufficient labour available at a low wage level, it is very attractive for

companies to outsource their production to these sites. This creates new jobs in the host

countries (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2009). The

transport and logistics sectors have a greater impact on the labour market in developing

countries than in industrialised countries. In developing countries, unemployment rates

are often especially high as large segments of the population are excluded from the labour

market. For the poorest developing countries, transport and logistics offer new

employment opportunities for a significant proportion of the population (Shepherd, 2013).

Confirming the positive impact of LP on trade and FDI would increase and emphasise

the need for sophisticated logistics in the observed countries and justify investments in LP.

2.4 Development of the frame reference

For our study it seems reasonable to focus on developing countries because these

countries can still have capacity to achieve considerable improvements in LP. On the

other hand, improvements in LP for developed countries would only be marginal.

Overall, developing countries can benefit more from FDI than developed countries

(Blomström et al., 2001). Memedovic et al. (2008) identified large differences in the LP

of countries at differing developmental stages. According to the authors, developing

countries have a special potential to expand their logistical infrastructure in order to

achieve growth effects. Developing countries have rather inefficient transport systems

where mainly roads are accessible. Due to this poor LP there is a high risk for these

countries to become isolated from world markets (Memedovic et al., 2008).

Shortcomings in developing countries in the areas of transport and telecommunications as

well as inadequate staff skills, supplier availability and quality, equipment and

technology present challenges that do not normally arise in developed countries. These

difficulties hinder the extent to which a global supply chain offers a competitive

advantage (Meixell and Gargeya, 2005). The analysis in this article can therefore help to 34 S. Lutterman n et al.

identify precisely those areas of LP through which countries can benefit from

international trade and investment flows.

The hypotheses that will be checked in this study are the following:

H1a LP affects the export flows of a country positively.

H1b LP affects the import flows of a country positively. H2

LP affects the FDIs positively.

Figure 1 shows these considerations. Figure 1 Research object 3 Methodology 3.1 Basic considerations

The theoretical notions are going to be tested by using a dataset consisting of various

secondary data sources referring to a panel data analysis for analysing the developments

within a time frame between 2006 and 2017. Table 1 Investigation units No. Country No. Country 1 Bangladesh 11 Myanmar 2 Bhutan 12 Nepal 3 Hong Kong 13 Pakistan 4 India 14 Philippines 5 Indonesia 15 Singapore 6 Japan 16 Sri Lanka 7 Cambodia 17 South Korea 8 Laos 18 Taiwan 9 Malaysia 19 Thailand 10 Mongolia 20 Vietnam

The impact of logistics performance on exports, imports and FDI 35

The analysis refers to 20 countries of three Asian sub regions (East Asia, Southeast Asia

and South Asia) as the world investment report has indicated those three areas as being

significantly important for trade and FDI (UNCTAD, 2018) and the necessary amount of

data was available for this sample set (see Table 1). We excluded China as this country

has been identified as an extreme outlier that would have biased our results.

Most of these countries are classified by the OECD as developing countries and in the

past years their FDI has increased significantly (UNCTAD, 2015). Furthermore, this

group of countries is an interesting object of investigation, since the share of logistics

costs in total costs is twice as high in developing countries as in industrialised countries,

which has an impact on the overall performance of companies that operate in these

countries (Straube et al., 2008). 3.2 Used data

To operationalise the components of LP empirically, we refer to data from the LPI and

the GCI. We use LPI data from the years 2007, 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2016. Thereby the

six preceding categories (refer to previous note) and the ‘LPI overall index’ are used.

Each of the seven variables is measured on an ordinal scale between 1 and 5 whereby 1

indicates the lowest and 5 the highest value. Furthermore, we used the annual GCI data

from 2006 to 2017. The GCI provides data on the quality of road, port, airport and

railway infrastructure as well as an overall index of transport infrastructure. These five

variables are measured on a scale from 1 to 7 whereby 1 indicates the lowest value and 7

indicates the highest value. The GCI is provided by the World Economic Forum on an

annual basis. It measures the competitiveness of a country and identifies barriers that may

lower a country’s competitiveness. For the purpose of this paper, the GCI offers a good

possibility to operationalise the transport infrastructure of countries as it includes

different variables that are used to measure the quality of each traffic mean (Martí et al., 2014).

Six of the 12 logistics variables for LP aim at measuring means of traffic emphasising

a significant importance to describe transport infrastructure. Transport and associated

handling operations represent the highest cost factor of international goods flows. Hence,

it is of great interest to companies that the transport networks in a country are well

developed. Infrastructure is an essential component in trade processes as it supports the

physical movement of goods (Limão and Venables, 2002; Schieck, 2008).

Trade volume data used in this study includes exports as well as imports. For the

purpose of this study, we also use data that includes yearly ‘FDI Inflows’ which capture

the value of cross-border transactions. Basically, we look at how much has been invested

into these countries per year.

Following the notions of Khadaroo and Seetanah (2009) and Shah (2014), we use

macro-economic stability, market size as well as labour as control variables, as they also

have an impact on trade and investment activities. In particular, many developing

countries have deficits in terms of macroeconomic stability. These include the

performance of state structures, the political participation of citizens or corruption. Only

as long as the performance of the government is strong will it be profitable for companies

to invest in a country (Shah, 2014). The ‘worldwide governance indicators’ are used to

accessed the macro-economic stability of the countries studied. For foreign investors, the

size of the host country is also an important element in the investment decision. The

market size reflects the potential of possible demand (Khadaroo and Seetanah, 2009). In 36 S. Lutterman n et al.

our approach, market size is represented by the proxies ‘total population’ and ‘GDP per

capita’. Personnel costs are an important component of total production costs and

personnel has a great influence on the productivity of the companies. We use ‘labour

force’ to include general labour supply as a control variable (Khadaroo and Seetanah, 2009).

Table 2 summarises the variables used in our work. Table 2

Set of variables used for the analysis No. Source Variable 1 World Economic

‘Quality of overall infrastructure’ Logistics 2 Forum ‘GCI road’ performance 3 ‘GCI rail’ 4 ‘GCI water’ 5 ‘GCI air’ 6 The World Bank ‘Overall LPI score’ 7 ‘LPI customs’ 8 ‘LPI infrastructure’ 9

‘LPI Ease of arranging shipments’ 10

‘LPI quality of logistics services’ 11

‘LPI tracking and tracing’ 12 ‘LPI timeliness’ 13 UNCTAD ‘FDI inflows’ Dependent 14 ‘Exports’ variables 15 ‘Imports’ 16 ‘Labour force’ Control variables 17 ‘Total population’ 18 ‘GDP per capita’ 19 The World Bank

‘Worldwide governance indicators’ 3.3 Analysis methods

The analytical examination of the assumed relationships was performed in three steps:

• First, we analysed the logistical data separately in order to obtain specific

information on a country’s LP. This shows which areas offer room for improvement

and how LP has developed over time. Overall, this step allows the identification of

strengths and weaknesses of the examination units in regards to LP.

• Next, we compared LP data with the trade volume and FDI data using scatter

diagrams as these allow first insights on the relationship. The diagrams show

whether a high LP leads to high FDI as well as high export and import flows. We

then used the aggregated GCI and LPI indices on the x-axis and the investment and

trade flows on the y-axis. This step corresponds to a static analysis as no time series

or the heterogeneity of the countries examined is considered.

The impact of logistics performance on exports, imports and FDI 37

• Third, we performed a panel data analysis by considering the control variables and

worked out individual timely effects of the logistical indicators on FDI and trade

volumes as well as the size of these effects. In contrast to static scatter diagrams,

panel data analysis can be seen as a dynamic analysis step. Equation (1) presents the

general description of a panel data analysis (Baltagi, 2005): Y =α + x′ β + u i=1,…, N it it it (1) t =1, , … T

In our case, trade and investment data represent the dependent variable (Yit) while the

logistical factors as well as the control variables represent the independent variables(x’it).

The index i indicates the observation units and t indicates the time. α represents an

expression for a scalar axis intercept parameter that is invariant for time as well as for the

unit. uit represents an error term that includes individual effects that are not observable

(Baltagi, 2005). In order to analyse our data, we used the program ‘GNU regression,

econometric and time-series library’ (Cottrell and Lucchetti, 2019) and analysed the data

with an adequate panel estimator (e.g., fixed effect estimator). The interpretation of our

results is based on the sign as well as the significance level of the variables. A positive

sign of the independent variable describes a positive influence on the dependent variable

and a negative sign accordingly describes a negative influence. The significance-level is

documented by a p-value that should be smaller than 0.1 indicating a significant

relationship on a 10%-level (Schendera, 2014). 4 Analysis and discussion

4.1 Characterisation of the country specific LP

Figure 2 shows the development of the four GCI categories over time. The presented

value is the average value based on the data for all 20 countries and shows the average

performance of means of traffic.

Figure 2 GCI development over time (see online version for colours) 7.00 6.00 Road 5.00 Rail 4.00 Water 3.00 Air 2.00 1.00 38 S. Lutterman n et al.

Overall, it can be stated that the countries examined receive a mediocre evaluation with

regard to the GCI data. On a possible scale up to a value of 7, the observed values range

from 3 to a maximum of 4.7 which represents an overall average condition of the four modes of transport.

This shows that there is still potential for improving the infrastructure within these

countries. Looking at the means of traffic on an individual basis, we can see that only

small improvements were observed. The best developed mode of transport is, according

to the GCI, the quality of airport infrastructure (mean value of 4.22 in 2017). On the other

hand, compared to all the other means of traffic, rail infrastructure represents the lowest

quality. However, rail infrastructure was first evaluated in 2009 with an average value of

3.09 and by 2017 this result had slightly improved. Road infrastructure showed the

highest growth with an increase of 0.88 points within the time period from 2006 to 2017.

However, with an average of 4.1 in 2017, road infrastructure can still be considered to be

of low quality. Sea ports also showed a minor increase within the observed time period

and were evaluated with a value of 3.99 in 2017. Singapore and Japan achieved the

highest values in our sample while Myanmar, Mongolia and Cambodia were the worst

performing countries. The biggest difference between these countries becomes apparent

with the quality of railroad infrastructure. Here, Japan achieved the maximum value of

6.58 in 2017 while Cambodia only reaches a value of 1.64 in 2017 and represents the minimum.

Figure 3 shows the timely development of the six LPI categories.

Figure 3 LPI development over time (see online version for colours)

Also here, all categories were rated mediocre. The best category is ‘LPI timeliness’ with

a value of 3.49 in 2016, which describes the frequency with which shipments reach the

receiver within a given time window. The worst category was ‘LPI infrastructure’ with a

value of only 2.7 in 2016. However, this category as well as the category ‘LPI tracking

and tracing’ showed the highest improvement rates. With a value of 2.72 in 2016, the

category ‘LPI customs’ received a very low evaluation, as with all the other categories

too. Again, no positive development was visible. The remaining categories are ranked in

a medium position and only showed slight improvements in the evaluation over time.

Similar to the results of the GCI in most categories Singapore was the leading country in

our sample and Myanmar represented the most lagging country. For example, at the

The impact of logistics performance on exports, imports and FDI 39

category ‘LPI customs’, Singapore reached a value of 4.18 in 2016 while Myanmar could only achieve 2.43 in 2016.

For both indices, GCI and LPI, we were able to observe similar patterns with only

slight positive improvements as well as evaluation values indicating mediocre results.

These results however are typical for developing countries and show potential for improvements in all areas.

Our assumption is that increased LP will have a positive impact on trade and

investment flows. However, since LP is not generally at a good level in our research unit,

LP would rather represent a barrier to trade and investment. The further aim of this

analysis is to identify those areas which can have a positive impact on trade and

investment flows. Countries would then have to invest accordingly in these areas to

improve their LP in order to achieve positive effects on trade and investment.

Whether these improvements have positive effects on investments and trade flows

will be shown in the panel data analysis.

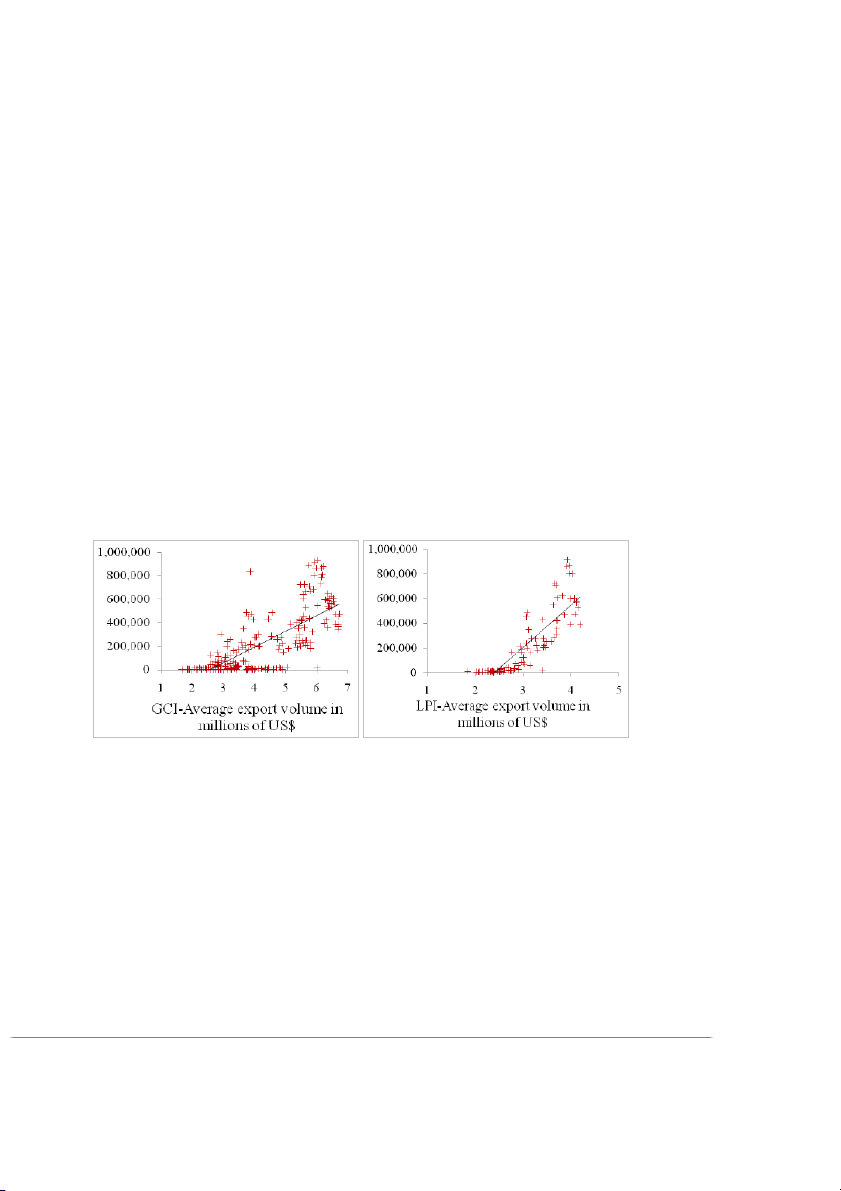

4.2 Static analysis of the relationship between LP and trade/investments

Figures 4, 5 and 6 show the relationship between GCI and LPI with the application of

scatter diagrams and offers a first approximation of the influence of LP on trade and

investments. The ‘overall LPI score’ is used to represent the six categories of the LPI.

This is the average of the six dimensions of trade presented. The ‘quality of overall

infrastructure’ of the GCI is also an overall index of all modes of transport and therefore

shows an overall picture of the transport infrastructure.

Figure 4 Scatter diagrams: logistics – exports (see online version for colours)

We were able to identify dependencies between logistics and trade flows as well as

investments in all figures (shown by the linear trend line). The figures show that the

average export and import flows as well as investment volume increases with LP. We are

thereby able to see that the LPI shows a more significant pattern than the GCI.

This visual representation is a first confirmation of the influence of LP on trade

volumes and FDI which supports our hypotheses. Although the correlation in investment

flows is not as pronounced as in trade flows, it generally shows that logistical factors can

play a role for companies in their investment decisions. This influence is further analysed

by the use of panel data analysis. 40 S. Lutterman n et al.

Figure 5 Scatter diagrams: logistics – imports (see online version for colours)

Figure 6 Scatter diagrams: logistics – FDI inflows (see online version for colours)

4.3 Dynamic analysis of the relationship between LP and trade/investments

We did not test the logistical indices jointly due to their high correlations, which would

have led to biased results. We therefore undertook computations for each of the six

LPI-variables as well as for the four GCI-variables in individual analysis steps. This

approach resulted in 30 output tables, which are not presented in detail in this paper.

Instead, we report only those results that showed a statistically significant influence on

exports, imports and FDI. Table 3 summarises the results of the panel data analysis.

Influence of LP on exports and imports

Our results identify that several of the logistical variables, in addition to some of the

control variables impact significantly on the export and import volumes of the analysed

countries (see Table 3). When considering exports as well as imports, four of the ten

logistical variables have a statistically significant influence on trade flows.

‘GCI road’ and ‘GCI water’ have a highly significant influence (p < .01) on export

and import flows showing the important role of roads and ports in international trade. The

significance of ‘LPI infrastructure’ (p < .05) also supports the importance of the transport

infrastructure for international trade. ‘LPI Ease of arranging shipments’ shows a

The impact of logistics performance on exports, imports and FDI 41

significant influence for exports (p < .05) and for imports (p < .1) meaning that it is an

important prerequisite for a country’s capabilities in organising competitive transport possibilities. Table 3

Results from panel data analysis Logistics variable Exports Sign Imports Sign FDI inflows Sign ‘GCI road’ *** + *** + * + ‘GCI rail’ 0 / 0 / ** + ‘GCI water’ *** + ** + ** + ‘GCI air’ 0 / 0 / 0 / ‘LPI customs’ 0 / 0 / 0 / ‘LPI infrastructure’ ** + ** + 0 /

‘LPI ease of arranging shipments’ ** + * + 0 /

‘LPI quality of logistics services’ 0 / 0 / 0 /

‘LPI tracking and tracing’ 0 / 0 / * + ‘LPI timeliness’ 0 / 0 / *** + ‘Labour force’ 0 / 0 / * + ‘Total population’ * + * + * + ‘GDP per capita’ *** + *** + * +

‘Worldwide governance indicators’ *** + *** + ** +

Notes: * significant on a 10 % level, ** significant on a 5 % level,

*** significant on a 1 % level, 0 = not significant.

Looking at the control variables, a statistical significance can be determined for the

variables ‘GDP per capita’ and for the ‘worldwide governance indicators’ (p < .01) and

sufficiently as well as for ‘Total population’ (p < .1).

Taking these results into consideration, we are able to partly confirm our first

hypothesis as our findings show that four out of ten LP indicators positively affect the

export and import flows of a country.

Our findings correspond with the explanations in the previous sections and confirm

the close links between logistics and international trade. Accordingly, we can recommend

that political decision-makers pay attention to the development of good transport

infrastructure, especially ports and roads. Influence of LP on FDI

The findings of our research also show a significant impact of our logistical variables on

FDI. ‘LPI timeliness’ (p < .01), ‘GCI rail’ and ‘GCI water’ (p < .05) as well as ‘GCI

road’ and ‘LPI tracking and tracing’ (p < .1) show a significant influence at an acceptable

level. As with exports and imports, it is also the transport infrastructure that is highly

significant for investments from abroad.

Also, some of the control variables are statistically significant. Looking at the

variable ‘labour force’ (p < .1), we can provide enough proof to show that more

cost-effective production due to low labour costs is a significant factor. This is

particularly important for companies pursuing the so-called resource-seeking strategy 42 S. Lutterman n et al.

(Dunning and Lundan, 2008). The main objective for companies in resource-seeking is to

acquire resources that are not available in their home environment or are available in the

host country at a lower price (Dunning and Lundan, 2008). The other effects of our

control variables ‘GDP per capita’ and ‘total population’ are of relevance for those

companies that opt for a market-seeking strategy. Market-seeking describes the plans of

multinational companies to open up new markets and thus reach new customer bases

(Dunning, 1998). This strategy can be supported by our results with ‘GDP per capita’ and

‘total population’ (p < .1).

Consequently, our hypothesis that LP indicators affect investment flows positively

can also be partially accepted. Five out of the ten logistics variables have a significant

influence on FDI inflows. Our findings support the results of a few studies that have

considered LP as a driver for FDI.

Our results on the influence of LP on international trade and FDI show new insights,

which further deepen the findings of previous studies such as Blyde and Molina (2015)

and Khadaroo and Seetanah (2009) as the influence of transport infrastructure on FDI can

be supported by ‘GCI road’ and ‘GCI rail’. Nevertheless, the studies by Martí et al.

(2017) and Gani (2017) show a significantly stronger influence of the LPI variables on

exports and imports. Only the categories ‘LPI infrastructure’ and ‘LPI Ease of arranging

shipments’ have a significant influence in our results. However, the comparison of our

results with the presented studies is not fully possible as we examined other countries,

different time periods and used different methods. 5 Conclusions and outlook 5.1 Conclusions

The purpose of our paper was to identify the influence of LP on trade and investment

flows. In order to test these relationships, we carried out an analysis in three steps. In the

first step we looked at the general development of the LP of the countries examined. The

research unit shows sufficient room for improvement in the six categories of the LPI and

the four categories of the GCI, as the data series are at a low to medium level.

Furthermore, only marginal changes in the LP of the countries could be detected over the

period under consideration. In a second step, we compared the data on the LP with those

on trade and investment. Here we were able to show that an increase in LP of a country

leads to an increase in trade volume and FDI volume. However, the LPI variables showed

better results than the GCI variables.

Our panel data analysis results show an acceptable influence of LP on exports and

imports. A total of four out of the ten logistical variables have a significant influence on

these volumes. In particular ‘GCI road’, ‘GCI water’ and ‘LPI infrastructure’ show

significance on the 1% level (respectively on the 5% level for ‘LPI infrastructure’),

demonstrating the particular importance of transport modes, ‘GCI road’ and ‘GCI water’

as well as ‘LPI infrastructure’ in general for developing countries. Significant values

regarding the influence of LP on FDI were also found. The influence of the transport

infrastructure should also be emphasised here, but ‘LPI timeliness’ and ‘LPI tracking and

tracing’ are statistically significant in contrast to our results regarding exports and imports.

The impact of logistics performance on exports, imports and FDI 43

Overall, we can conclude that our hypotheses are partially accepted as LP influences

the trade performance of the countries in our sample and the amount of FDI.

5.2 Implications and limitations

For states and governments, our findings help to identify improvement potentials in order

to be more internationally competitive as a country. Recommendations for action to

expand LP to achieve economic and social goals can be developed. Countries may not

have yet recognised the value of LP for them. Improved transport infrastructure

strengthens the ability of lesser developed countries to participate in global markets, as

well as improve their competitive position in order to keep up with other countries in the

industrialised world. A recommendation for decision makers, primarily policy makers, is

to therefore consider about the potential benefits that an improvement of the transport

infrastructure, especially roads and ports, can have.

Our model included a number of logistical variables in order to measure the LP;

however, the selection was limited so that only a part of the LP is included. Nevertheless,

it was necessary to operationalise LP with measurable values which excluded some other

aspects of LP such as working telecommunication networks that enables an efficient

information flow. This aspect was not considered in this paper due to the lack of

accessible data. Because LP is a highly complex construct and due to the restrictions in

data collection, this work did not include all the mentioned aspects of LP. Even if this

somewhat restricts the view of LP, it still appears to make sense to focus on

transportation because in international logistics transport remains a dominant activity

(Schieck, 2008) and logistics and transport are often treated equally (Ihde, 1972; Pfohl, 2018).

The availability of the LPI data was a decisive factor in the choice of the observation

period. Since the LPI has not existed for long, the period under consideration from 2006

to 2017 may be too short in order to identify significant trends. This is also reflected in

the analysis of the development of the logistics indices; only slight trends can be seen

here. The global economic crisis in 2008 also had a significant impact on all data

collected, with a marked reduction in trade and investment data from 2008 to 2009. This

distorts the trend curves and can also influence further analysis. 5.3 Outlook

A suitable model for the LP of countries should be developed that considers more than

just the transport infrastructure. Here, for example, ICT or the supply environment could play a greater role.

In the area of investments, approaches are needed which consider that different

aspects of LP may be more important, depending on the corporate strategy and

motivation for investment. The method presented can be extended by a sector-specific

analysis, as there are sectors that are more dependent on logistics than others. The state of

development of the countries studied can also be examined more closely, since the

influence of LP in industrialised countries is different from that in developing countries.

The fact that only slight positive improvements can be seen in our sample is an

indication that improving LP may be a long-term process. Therefore, in the case of a

growing importance of logistics for location decisions in emerging countries, as well as

The impact of logistics performance on exports, imports and FDI 45

Khadaroo, J. and Seetanah, B. (2009) ‘The role of transport infrastructure in FDI: evidence from

Africa using GMM estimates’, Journal of Transport Economics and Policy (JTEP), Vol. 43, No. 3, pp.365–384.

Khan, S.A.R., Qianli, D., SongBo, W., Zaman, K. and Zhang, Y. (2017) ‘Environmental logistics

performance indicators affecting per capita income and sectoral growth: evidence from a panel

of selected global ranked logistics countries’, Environmental Science and Pollution Research,

Vol. 24 No. 2, pp.1518–1531.

Limão, N. and Venables, A.J. (2002) ‘Infrastructure, geographical disadvantage, transport costs,

and trade’, The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp.451–479.

Lu, Q., Cai, S., Goh, M. and De Souza, R. (2010) ‘Logistics capability as a factor in foreign direct

investment location choice’, Presented at the IEEE International Conference on Management

of Innovation & Technology, IEEE, Singapore, Singapore, pp.163–168.

Makki, S.S. and Somwaru, A. (2004) ‘Impact of foreign direct investment and trade on economic

growth: evidence from developing countries’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 86, No. 3, pp.795–801.

Martí, L., Martín, J.C. and Puertas, R. (2017) ‘A DEA-logistics performance index’, Journal of

Applied Economics, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp.169–192.

Martí, L., Puertas, R. and García, L. (2014) ‘The importance of the logistics performance index in

international trade’, Applied Eco nomics, Vol. 46, No. 24, pp.2982–2992.

Meixell, M.J. and Gargeya, V.B. (2005) ‘Global supply chain design: a literature review and

critique’, Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, Vol. 41, No. 6, pp.531–550.

Memedovic, O., Ojala, L., Rodrigue, J-P. and Naula, T. (2008) ‘Fuelling the global value chains:

what role for logistics capabilities?’, International Journal of Technological Learning,

Innovation and Development, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp.353–374.

Millán, P.C., Agüeros, M., Hontañón, P.C. and Pesquera, M.Á. (2013) ‘Impact of logistics

performance on world economic growth (2007–2012)’, World Review of Intermodal

Transportation Research, Vol. 4, No. 4, p.300.

North, D.C. (1991) ‘Institutions’, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp.97–112.

Novik, A. and de Crombrugghe, A. (2018) Towards an International Framework for Investment Facilitation, OECD.

Ojala, L. and Rantasila, K. (2012) Measurement of National-Level Logistics Costs and

Performance, Discussion Paper No. 2012/04, OECD/International Transport Forum [online]

https://doi.org/10.1787/5k8zvv79pzkk-en.

Önsel Ekici, Ş., Kabak, Ö. and Ülengin, F., (2016) ‘Linking to compete: logistics and global

competitiveness interaction’, Transport Policy, Vol. 48, pp.117–128 [online] https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.01.015.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2009) OECD Insights International

Trade: Free, Fair and Open?., Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,

Paris [online] http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=457340 (accessed 13 April 2017).

Pfohl, H-C. (2018) Logistiksysteme, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Schendera, C.F. (2014) Regressionsanalyse Mit SPSS, Walter de Gruyter, 2nd ed., Odenbourg.

Schieck, A. (2008) Internationale Logistik: Objekte, Prozesse Und Infrastrukturen

Grenzüberschreitender Güte rströme , Oldenbourg Verlag, München Wien.

Shah, M.H. (2014) ‘The significance of infrastructure for FDI inflow in developing countries’,

Journal of Life Economics, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp.1–16.

Shams, R. (2003) Regional Integration in Developing Countries: Some Lessons Based on Case

Studies, HWWA Discussion Paper, Nr. 251.

Shepherd, B. (2013) Aid for Trade and Value Chains in Transport and Logistics, OECD/WTO. 46 S. Lutterman n et al.

Straube, F., Ma, S. and Bohn, M. (2008) Internationalisation of Logistics Systems: How Chinese

and German Companies Enter Foreign Markets, Springer, Berlin.

UNCTAD (2018) World Investment Report 2018: Investment and New Industrial Policies, UN

[online] https://doi.org/10.18356/ebb78749-en (accessed 3 April 2019).

UNCTAD (Ed.). (2015) Reforming International Investment Governance, United Nations, New York.

Verhetsel, A., Kessels, R., Goos, P., Zijlstra, T., Blomme, N. and Cant, J. (2015) ‘Location of

logistics companies: a stated preference study to disentangle the impact of accessibility’,

Journal of Transport Geography, Vol. 42, pp.110–121.

Wong, W.P. and Tang, C.F. (2018) ‘The major determinants of logistic performance in a global

perspective: evidence from panel data analysis’, International Journal of Logistics Research

and Applications, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp.431–443.