Preview text:

What Does It Mean to Build Bauhaus “On Brand”? Save this article Save

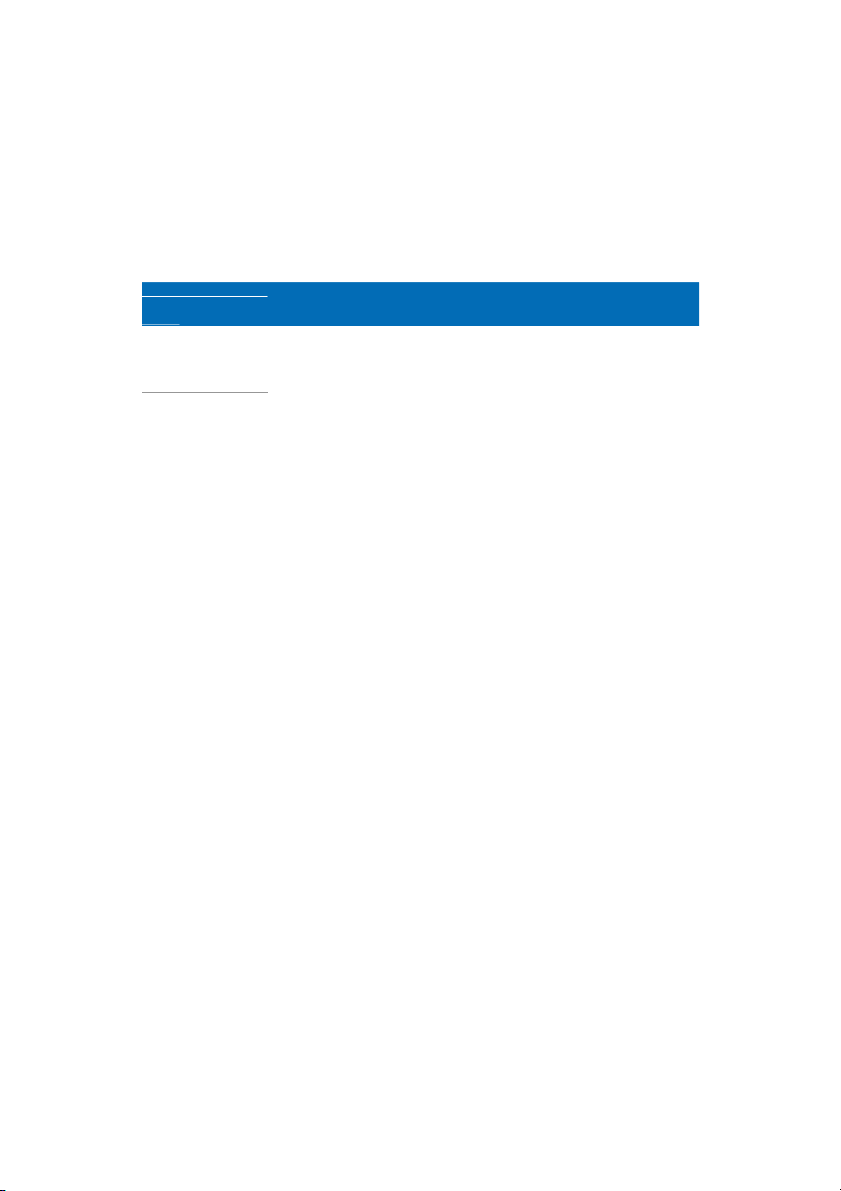

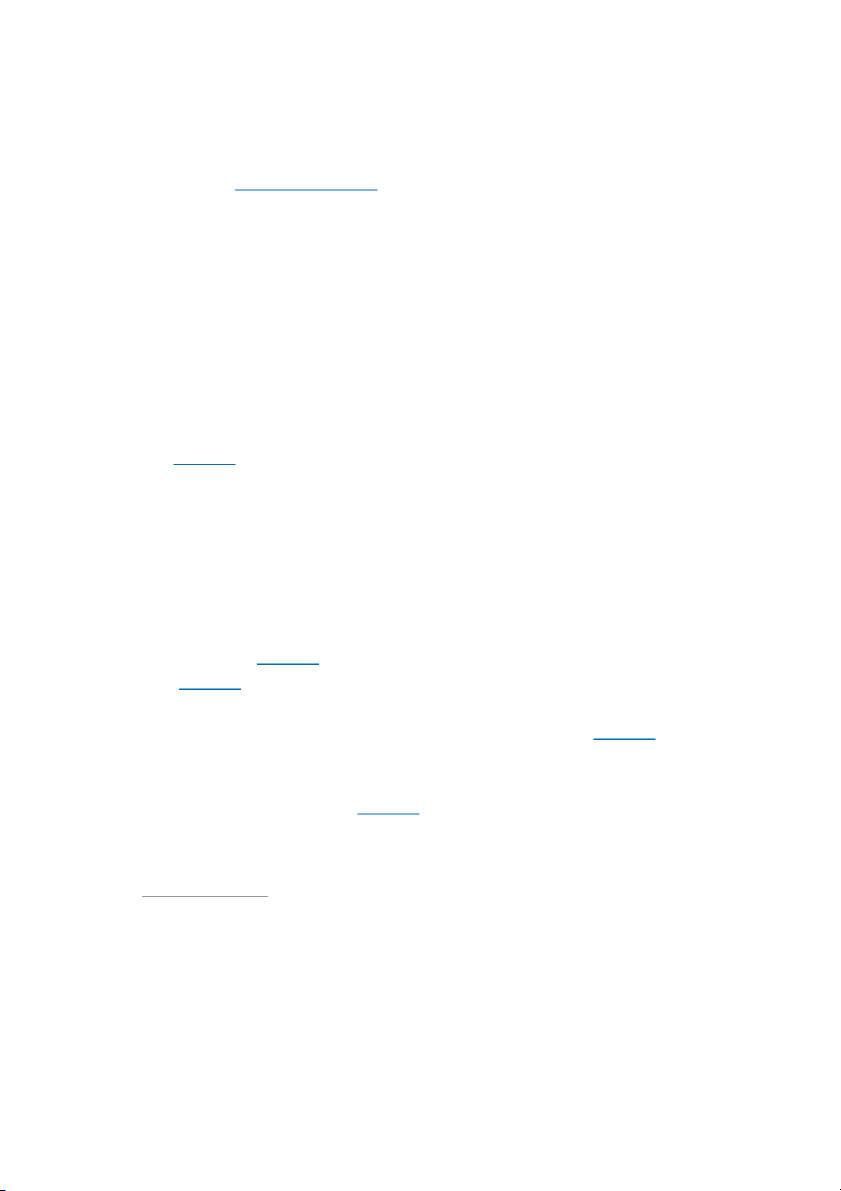

What Does It Mean to Build Bauhaus “On Brand”? Save this picture! The Bauhaus

Museum Weimar, designed by architect Heike Hanada, holds a vast collection of works dating

from the school’s first period (ca. 1919–23). Courtesy Thomas Müller/Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Written by Samuel Medina about 4 hours ago

in 2019, the Bauhaus turned 100 and a crop of museum buildings sprang up for the celebration.

In 2019, two museums bearing the name Bauhaus appeared on the German

culture circuit. Angling to capitalize on the design school’s centennial,

the Bauhaus Museum Weimar was first out of the gate, opening in early April;

a few clicks behind, the Bauhaus Museum Dessau followed suit in early

September. A third project, the much-delayed extension to Walter Gropius’s

1979 Bauhaus- Archiv/Museum für Gestaltung in Berlin, did not manage to

keep pace and isn’t expected to open for a couple more years yet.

At the moment in Berlin, kapitän Gropius’s keel is shipwrecked in a sea of

muddy ditches, its programming relocated to a temporary annex. The

building, which broke ground in 1976, the same year the kapitän’s Dessau

campus was restored by the German Democratic Republic, opened in 1979

and was never much loved, although footfalls dramatically increased after

the Wall came down. It is visibly the result of compromise: Gropius’s original

plans, drawn up in 1964 for a sloped site in the small city of Darmstadt near

Frankfurt, were waylaid by local politicians; only in the following decade,

after Gropius’s death, did the project find a site in then–West Berlin. The

dislocation did violence to the original scheme, however, requiring extensive

modifications by Gropius’s acolyte Alex Cvijanovic (not least among them

translating the building to flatland).

Whatever verve there was in that first project was methodically snuffed out

in the pallid final version. It is modular without the conviction for its logic,

and subtractive “without a flaming desire for new potentialities,” to borrow a

line from the critic Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, who seized every chance to

antagonize Gropius in his elder-statesman years. The surfaces—which,

contrary to the school’s reputation, were a source of much craftsmanly

anxiety for architects at the Bauhaus—are dull. The trademark shed roofs,

and the jaunty winding ramp added by Cvijanovic, strive for loftier heights

but don’t reach them. It was, and remains, not very Bauhaus.

The case of the Bauhaus-Archiv is instructive because it highlights the

problem of building “on brand,” especially a legacy brand like BAUHAUS. The

magic simply cannot be recaptured, as surely as tragedy passes into farce,

farce into memetic nihilism. While plenty of “modern” buildings are going up

in every city in the world, they have more in common with IKEA and the

lobotomizing virality of Alucobond than with the 20th century’s most famous design school. Save this picture!

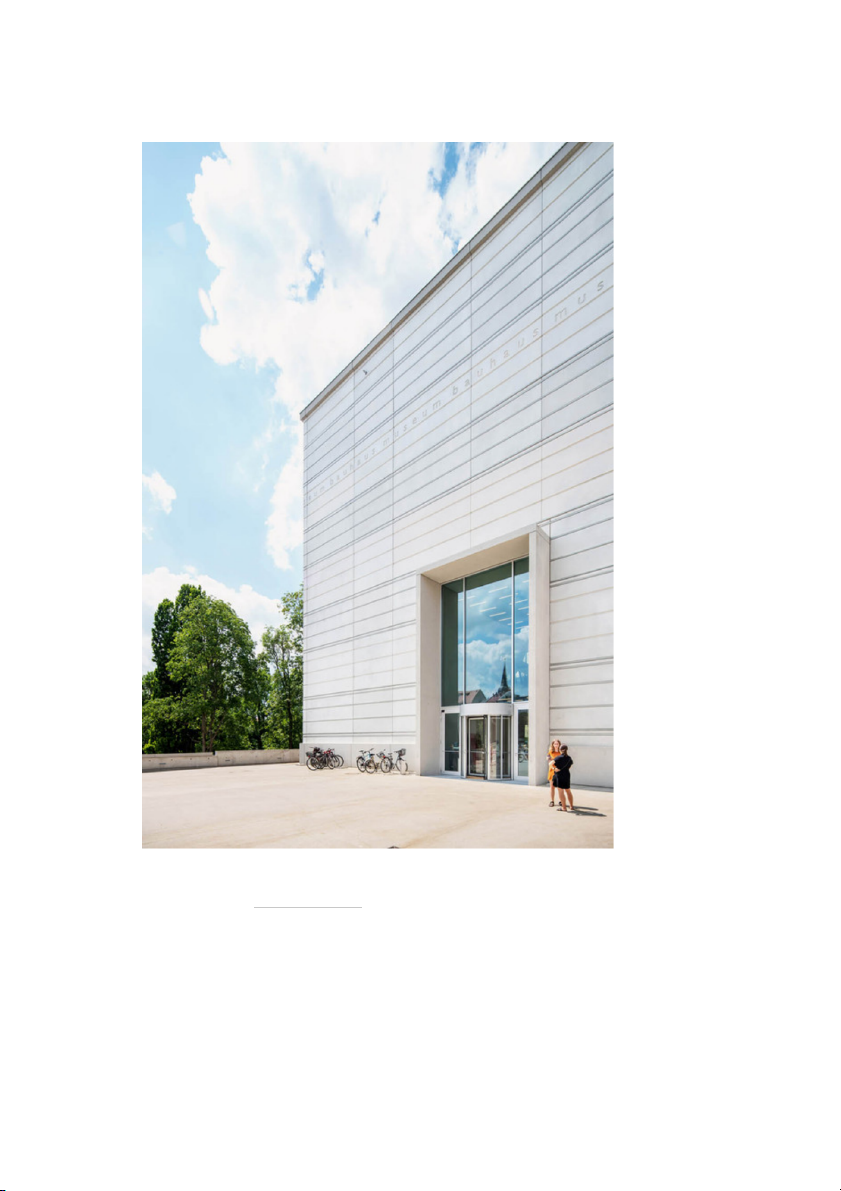

The 24,000 square feet of galleries at the Bauhaus Museum Weimar are arrayed around a primary

off-center staircase. The cubic building, whose smooth concrete is articulated in striations,

anchors the northeastern edge of a park in central Weimar. It is steps away from a former

administrative complex built and used by the Nazis. Courtesy Thomas Müller

The genius of the Bauhaus, such as it was, lay in the combustible political

situation that forced it into being. From the magma of world war emerged a

new spirituality, to which Gropius gave voice in his 1919 manifesto while

founding the school in Weimar. “Crystallization” is the key term, as in his

memorable exhortation: “Art must finally find its crystalline expression in a

great total work of art. And this great total work of art, this cathedral of the

future, will then shine with its abundance of light into the smallest objects of everyday life.”

It is no coincidence, then, that the most reproduced image of the Bauhaus’s

initial Weimar period was Lyonel Feininger’s depicting a prismatic woodcut

“cathedral of socialism.” This socialism was of the William Morris sort, earthy

and fraternal, bowing to sensuous feeling and species essence before

instrumental reason. Art, that is to say crafts, would be a prophylactic

against the mechanized terror of war prosecuted by the bourgeoisie at home and abroad.

What was required to face down this opposition was a surplus of feeling and

humanity, and what better place to take such a stand than in Weimar, the

nerve center of the German Enlightenment, home of Goethe and Schiller?

But soon, the expressionist Esperanto that wafted through

the Bauhaus workshops morphed into another design theodicy, more angular

and staccato, partly based on the work of the De Stijlist Theo van Doesburg.

Neither influence found particular purchase with the architect Heike Hanada,

who designed the Bauhaus Museum Weimar. A squat concrete cube, it

evinces a little of the angst that was latent in expressionism, but denies its

redemptive vector. Appropriate, given the importance of Weimar to the

Nazis’ machine-abetted policy of extermination, and the site’s proximity to

both the Gauforum (the administrative building where that policy was drawn

up) and the Buchenwald camp (where it was implemented). The museum’s

massing is leavened by only a few windows, giving off a feeling of intense

solidity. The strategy would appear to be one of internalized negative

enlightenment, if not for the airy interiors, which nonetheless suffer from an

overemphasis of the central, very narrow staircase. Save this picture!

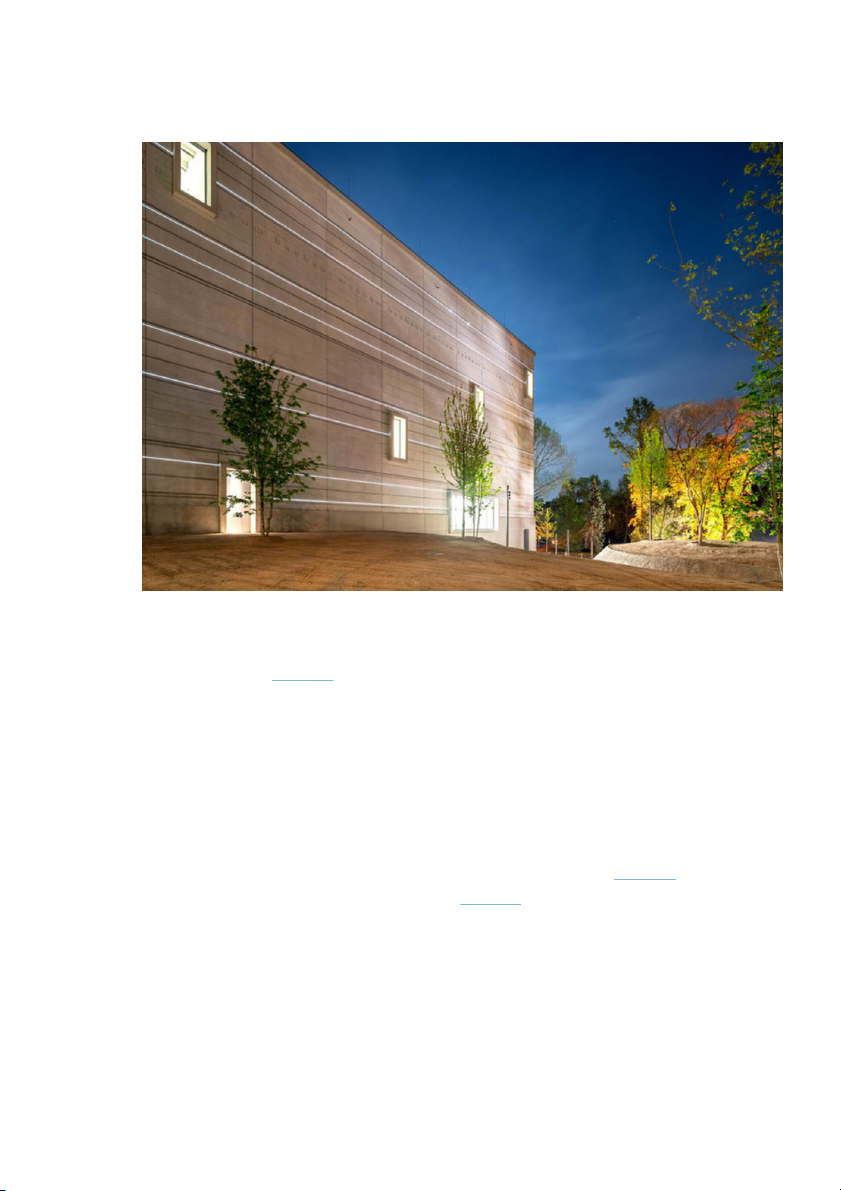

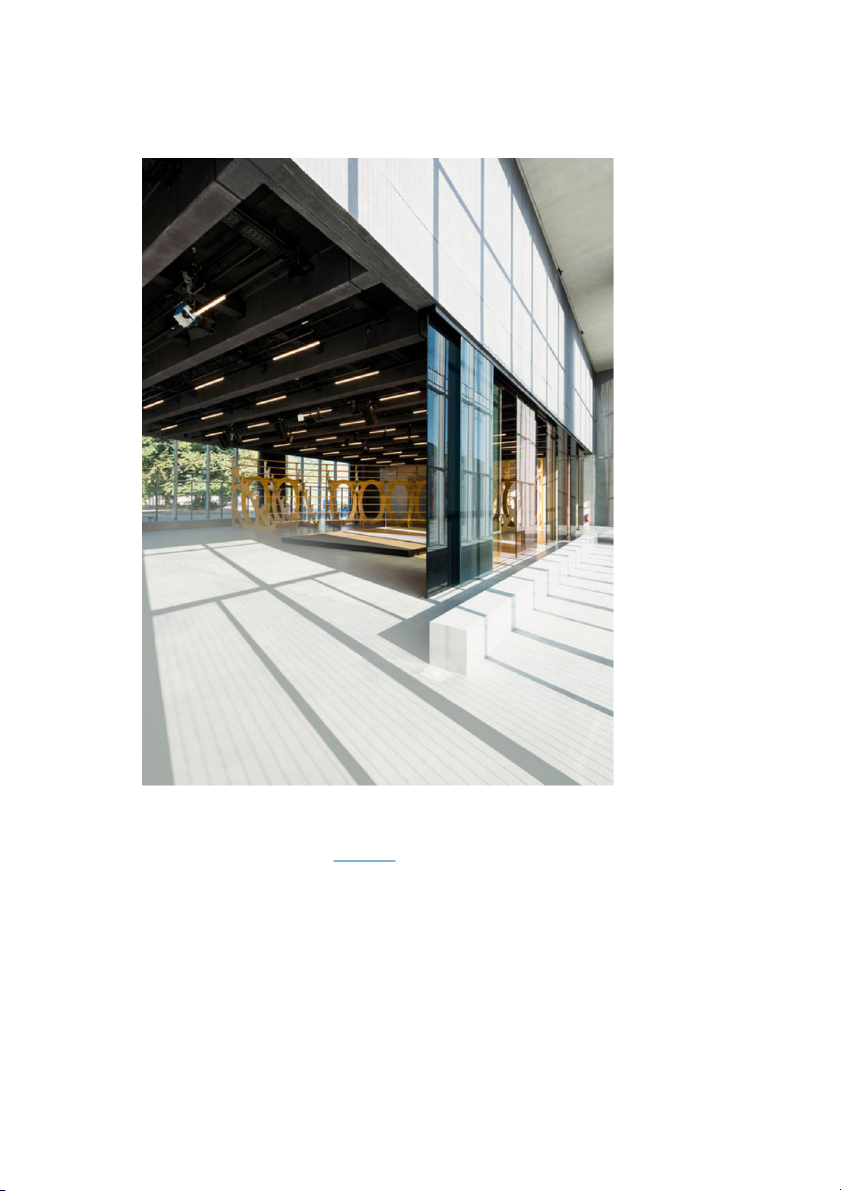

The second Bauhaus museum opened in Dessau this fall. The building was designed by the

Barcelona, Spain–based addenda architects. Courtesy Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau/Photo: Thomas Meyer/OSTKREUZ, 2019

For all this compression and heavy bearing, a “bunker” it is not, as some

critics have claimed. Architectural criticism has always had an uneasy pact

with simile. In this case, the temptation is understandable—being so close to

the Gauforum and its adjoining courtyard, which once bore the honorific

“Adolf Hitler-platz”—and, if anything, it points to a version of Godwin’s law:

Any discussion of the Bauhaus will lead to Nazism.

The school was first pushed out of Weimar when rankled provincial

authorities pulled its funding. It moved to Dessau, where the school had its

Golden Years on Gropius’s campus (1926), incubating. Gropius passed the

baton to the grinning communist (and architecturally his better) Hannes

Meyer. The school turned a profit, while at the same time, students began

more fully engaging with the world outside their workshops. This became a

problem and Meyer was forced out, with Mies van der Rohe stepping into the

breach. He gutted the curriculum and turned the focus away from workers’

housing—and advertising, painting, sculpture, and theater—to plateglass

Platonic villas. Student explorations into the riddles of industry and of history

were rechanneled into finger-to-lip probing of architectural form. But it didn’t

matter, because the brownshirts came, some even infiltrating the

Bauhäusler. They called the school the “aquarium” and booted it up to Berlin,

where it finally acquiesced to Kulturkampf browbeating.

The Bauhaus was among the first victims of the fascists, prompting the

dispersal of its leading lights across borders and hemispheres. (Again,

Moholy-Nagy: “In 1933 Hitler shook the tree and America picked up the fruit

of German genius.”) By the end of the decade, Gropius, Breuer, and others

had been welcomed into the heart of the American intellectual firmament,

and “Grope”—the obtuse nickname his new companions gave him—

preemptively began expunging the record. The Weimar period was binned in

toto, and the school’s socialist undercurrent was retconned. What was left

was his Dessau Bauhaus, an institution too modern for the Old Continent.

That Bauhaus was a linchpin in the CIA’s soft-power strategy to chip away at

the elevated status afforded to the Soviets after World War II. Dessau, both

the campus and the city, fell under Soviet control, but the real Bauhaus, like

democracy, lived on in the First World. As scholars such as Kathleen James-

Chakraborty have shown, the various modernities that existed up to,

alongside, and even after the Bauhaus in Germany—Neues Bauen,

expressionism, Weimar Lichtreklame—were formally subsumed into

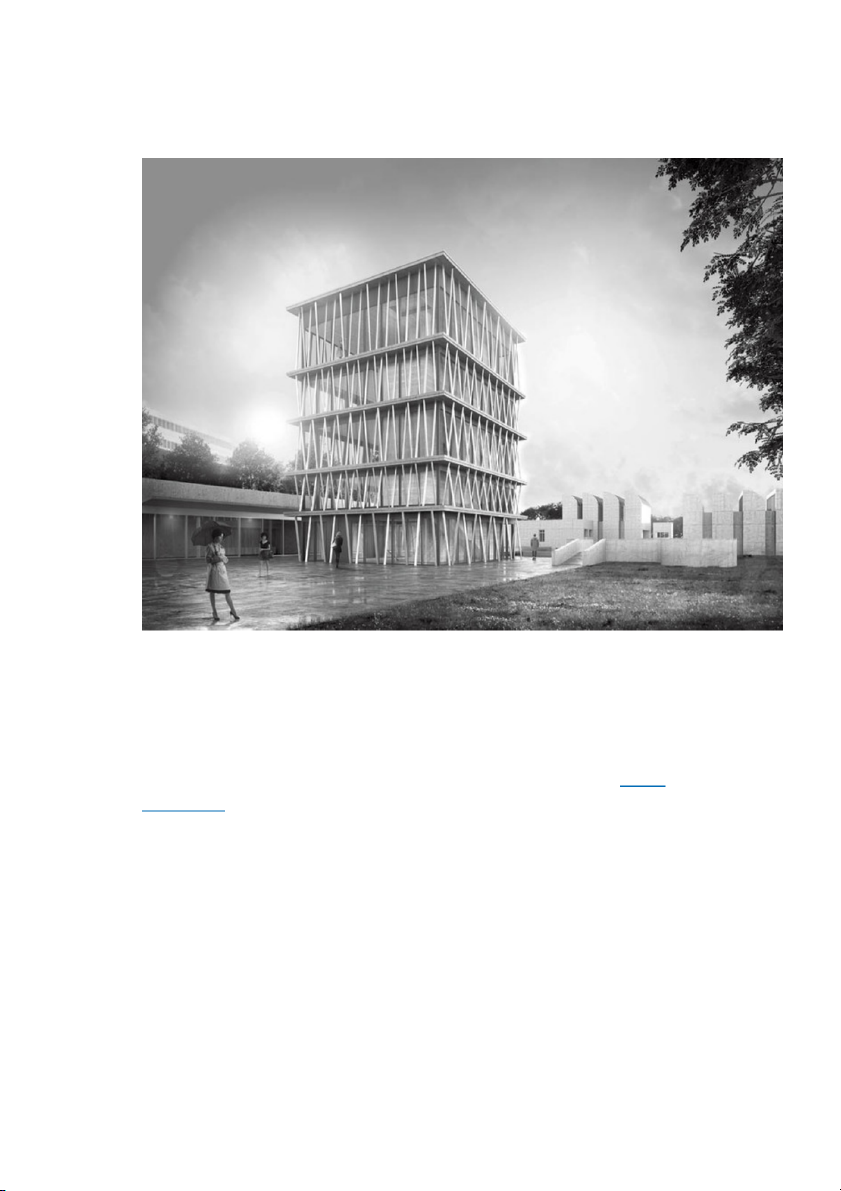

BAUHAUS, a brand to be imported throughout the NATO bloc. Save this picture! The new

museum stands in the heart of Dessau at the edge of a public park, a few miles away from the

famous Walter Gropius–designed campus. Courtesy Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau/Photo: Thomas Meyer/OSTKREUZ, 2019

But what counted for echt Bauhaus architecture in its homeland could be

counted on two hands. Apart from the school campus, there are textbook

buildings, like the totalizing villas Gropius built for Bauhaus masters

(variably, Kandinsky, Moholy-Nagy), and non-textbook, stucco-less works—

namely, Gropius’s Employment Office (1929) and Hannes Meyer’s

deceptively straightforward Houses with Balcony Access (1930). In Weimar,

the 1923 Haus am Horn was a first stab at the genre. Farther from the

Mitteldeutschland beat is Meyer’s 1930 ADGB Trade Union School in Bernau

outside Berlin; like the Dessau campus, it is chock-full of ideas—and

eminently usable ones at that—while not giving a fig about Gropius’s Sachlichkeit signaling.

Even a century on, these buildings still crackle through their sheer force of

example. Of course, one could do without the Lutheran purity, which was

subverted by the Bauhäusler anyway in their everyday social relations. Or

the flighty conceptual afflatus (“a new unity”) or technophilic hymning (art-

and- technology, technology-and-art, amen).

Thanks be given, then, to addenda architects, the Barcelona, Spain–based

studio behind the Bauhaus Museum Dessau. It has done away with the most

cloying proclivities of the Dessau gang, while keeping the hard lines and

modish typography. Which isn’t to say that the building is a standout. The

diagram is exceedingly simple, a classic void-solid relationship: A continuous

clear-span exhibition hall is suspended over a continuous clear- span mixed-

programming hall. The upper half is tinted black to conceal its contents,

while the bottom leaves the translucent envelope untouched.

So far, so self-effacing. But the glazing is not transparent as it should be,

given the building’s prominent siting in a large park in the town center. The

architects had imagined dematerializing the facade (very Bauhaus) to the

extent that inside and outside were blurred, but short of this, the museum’s

presence in the otherwise public space feels intrusive. Save this picture!

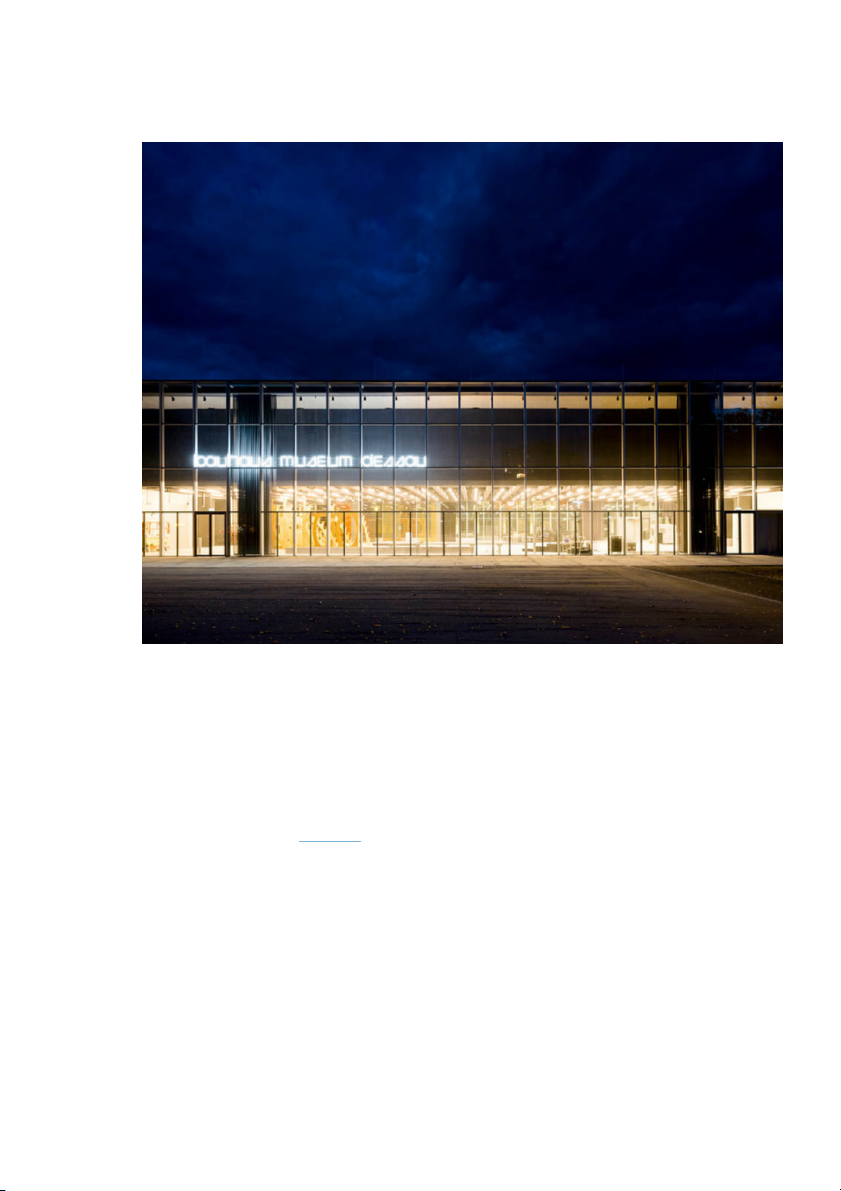

The extension to the Bauhaus-archiv in Berlin, by Staab Architekten, is due to open in

2021.Courtesy Staab Architekten Gmbh, Berlin

The museum extension in Berlin, meanwhile, is the most elegant design of

the new crop. The majority of the project will be concealed underground,

with a five-story towerlet being the only obvious superstructure in the plan. It

features gossamer-thin, parametrically ruled columns on the exterior, leaving

the interior floors (for a museum café and shop) completely open. Staab

Architekten, which was awarded the commission in 2015, was wise to put

some distance between the extant building and its own, the better to

disavow any outright influence.

It is ironic that the Bauhaus’s claim to history largely hinges on the

architectural works imputed to it. Apart from Meyer’s buildings and the

Dessau campus, “Bauhaus architecture” is something of a misdirection. It

was the school’s other spheres of activity, from weaving to wallpaper design,

painting to advertising, that were pioneering, the ones that still manage to

capture our imagination. (Indeed, the Bauhaus lacked an architecture

program for much of its existence.)

If the Bauhaus were reconstituted in 2019, what would keep its students up

at night? Such is the question asked by the new book Bauhaus Futures (MIT

Press), and among the many diverse and timely responses, architecture—i.e.,

buildings—is nowhere to be found. But you can’t mount a massive tourism

campaign on living ideas—risky new IP—only on ossified ones.

Nor can you, prospective traveler, walk around inside an Albers tapestry. You

can’t inhabit a Klee painting or press up bodily against the contours of a

Brandt teakettle. But you can get on a plane, fly to Berlin, jump on a train to

Dessau, hail a taxi to 38 Gropiusallee, walk through those (redder-than-) red

doors and pose for photos on the staircases, buy picture books in the gift

shop, mourn your lost youth in the canteen. You can even spend the night. This article was on Metropolismag.com. originally published