Preview text:

JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH

DEPRESSION, AXIETY AND ASSOCIATED FACTORS

AMONG YOUNG PEOPLE DURING THE SECOND WAVE OF COVID-19 IN VIETNAM

Pham Phuong Mai1,2,*, Tran Nhu Hai1, Trinh Dinh Minh Viet2, Hoang Thi Hai Van1,2

1School of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Hanoi Medical University

2Center for Training and Research on Substance Abuse and HIV

This cross-sectional study was conducted nationwide with a sample size of 9.781 participants in order to

describe the prevalence of depression and anxiety among Vietnamese youth (15-24 years old) during a COVID-19

outbreak and associated factors. The 21-item Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale was used in this study.

Results showed that 10% of the Vietnamese youth exhibited mild to extremely severe depression and 15.6%

reported mild to extremely severe anxiety. Particularly, 1% of participants reported having severe or extremely

severe symptoms of depression and 2.6% having severe or extremely severe symptoms of anxiety. Being

christian or of other marital status or living in urban areas or having near poor or poor household income were

all associated with increased depression among young people. Meanwhile, youth who were female, of ethnic

minorities, Buddhist, Christian, or single, lived in urban areas, had only an elementary education, or had near

low or low household income reported more anxiety symptoms. Findings from this study call for appropriate

interventions to improve the mental health of the young population, especially in the context of COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Depression, Anxiety, Youth, COVID-19, Vietnam. I. INTRODUCTION

Mental health disorders are considered

The prevalence of mental health disorders

major global health problems, with more than

is increasing among youth - 1 in 10 people

54 million people experiencing a variety of

reported experiencing at least one mental health

mental disorder symptoms.1 Mental disorders

problem.6 Findings from the U.S. National Survey

were estimated to account for 32.4% of years

from 2009 to 2017 showed that the incidence of

lived with disability and 13% of disability-

depression increased by 52% in the 2005 - 2017

adjusted life years.2 As of 2017, among a

period among adolescents aged 12 - 17, and

wide range of mental health concerns, anxiety

63% in 2009 - 2017 among young adults aged

disorders were the most common forms of

18-25.7 Approximately, 20% of adolescents may

psychopathology and depression was one of

experienced a mental health disorder each year.8

the leading causes of disability with more than

and 50% and 75% experienced problems before

264 million people affected globally.3 Notably,

the age of 14 and by the age of 24, respectively.9

these mental concerns are among the most

There exists little research on the

prevalent psychological concerns for young

prevalence of depression and anxiety among

people4 and they often occur in comorbidity.5

young people in Vietnam in recent years

Corresponding author: Pham Phuong Mai

despite evidence of COVID-19 impacts on

Hanoi Medical University

mental health. According to a study by the

Email: phamphuongmai@hmu.edu.vn

U.S. CDC, during the outbreak of COVID-19 Received: 27/01/2022

from August 2020 to February 2021, the Accepted: 13/03/2022

incidence of depression or anxiety increased JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022 121 JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH

from 36.4% to 41.5% in seven days, mainly

Therefore, N ≥ 9312. Convenient sampling

among 18 to 29 years old.10 In Vietnam, little

was utilized to recruit participants in 2 months

is known about the prevalence of these mental

(from June 2020 to August 2020). Hanoi

disorders among youth during the COVID-19

medical students were trained to recruit and

pandemic. Extant literature while scarce,

conduct face-to-face interview using structured

rather focuses on the general Vietnamese

questionnaires at participants’ households in 12

population with predominant recruitment of

different provinces in Vietnam.

adult participants.11, 12 As such, we could find 2. Measures

only one study which highlighted approximately - Sociodemographic variables: were

9% of depressive and anxiety symptoms

composed of age, sex, ethnicity, marital status,

among Vietnamese young adults from 18 to 26

living area, education level, and economic status.

years old13 Still, there is insufficient evidence

on how commonly Vietnamese youth, defined

- Variables of depression and anxiety:

Previous research validated the use of DASS-

as between 14 and 25 years old by the World

21-V for Vietnamese adolescents, showing

Health Organization,14 experienceddepression

the scale’s adequate internal consistency and

and anxiety in a pandemic-related context.

convergent validity.15 18 DASS-21 is a 4-point

Therefore, this study aimed to describe

Likert scale (0 = ‘Did not apply to me at all-

the prevalence of depression and anxiety

Never’, 1 = ‘Applied to me to some degree, or

and associated factors among Vietnamese

some of the time–Sometimes’, 2 = ‘Applied to

young people during the second wave of the

me to a considerable degree, or a good part of COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

time - Often’, 3 = ‘Applied to me very much, or

II. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

most of the time - Almost always’), consisting of

21 items. Of which, items 3, 5, 10, 13, 16, 17,

1. Study participants and Procedures

and 21 are for depression and items 2, 4, 7, 9,

This was a cross-sectional study using

15, 19, and 20 are for anxiety. According to the

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-

scale, the subscale scores were calculated for 21) to measure the outcome.15

participants’ depression and anxiety by doubling

Eligible participants were those who were

the total scores in each subscale. Subscale

between 15 and 24 years old and could give

scores should range from 0-42. Participants

consent to participate in the study. People who

were categorized into different levels of clinical

were cognitively unable to give consent or severity:

answer questions were excluded from the study.

(1) Normal (0-9 for depression, 0-7 for anxiety);

To estimate the sample size, we used the

(2) Mild (10-13 for depression, 8-9 for anxiety); following formula:16

(3) Moderate (14-20 for depression, 10-14 for !(#$!) anxiety); N=Z2(1-α/2) &!

(4) Severe (21-27 for depression, 15-19 for In which: anxiety);

α (2-side significant level) = 0.1

(5) Extremely severe (≥ 28 for depression,

p (Expected proportion in population) = 0.03217 ≥ 20 for anxiety). d (absolute precision) = 0.003 3. Statistical Analysis 122 JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022 JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH

Data was entered and analyzed by STATA 4. Ethical issues

16 software. Findings that followed normal

This study was conducted with the approval

distribution were reported in percentage, means,

of the Institute for Preventive Medicine and

and standard deviation. Logistic regression

Public Health as the practicum module. We

was used to assess the relationship between

obtained full consent from participants before

sociodemographic variables and depression

data collection. All identifiable information was and anxiety prevalence.

recoded to ensure the confidentiality. III. RESULTS

1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

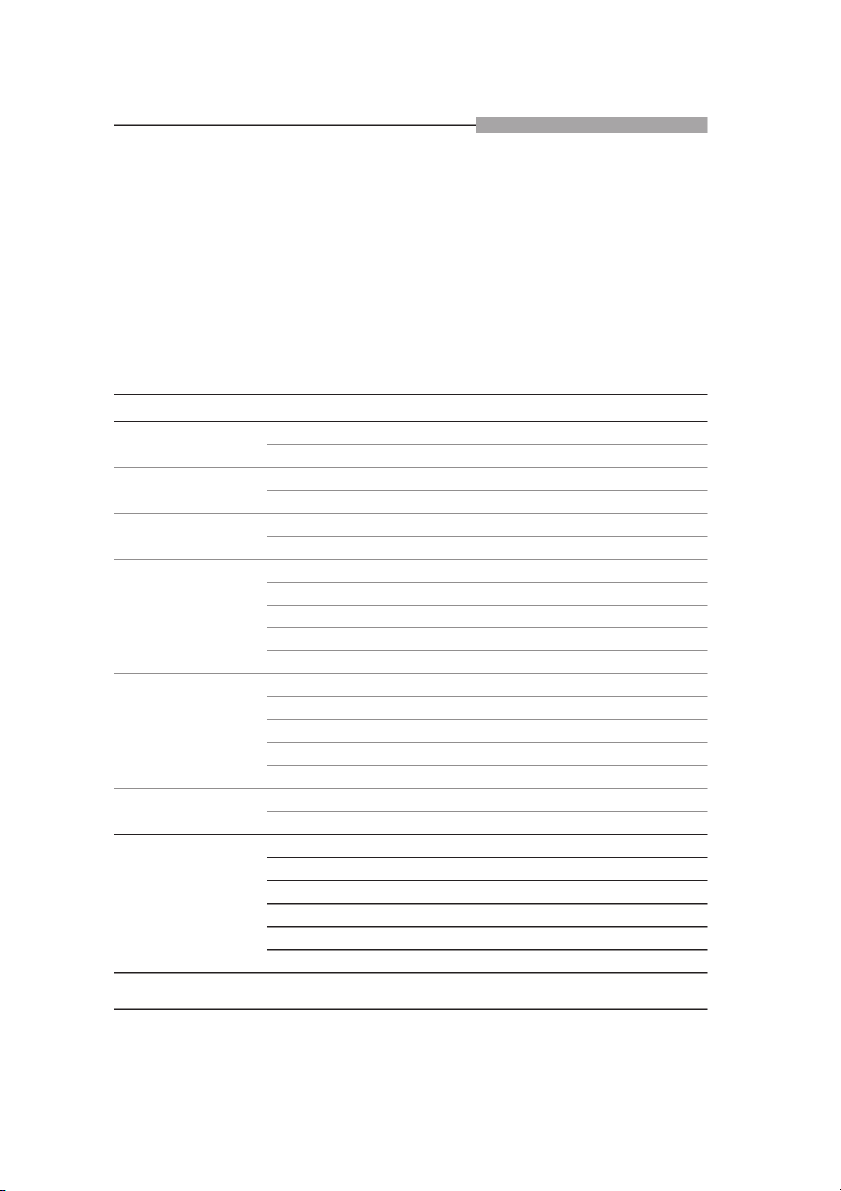

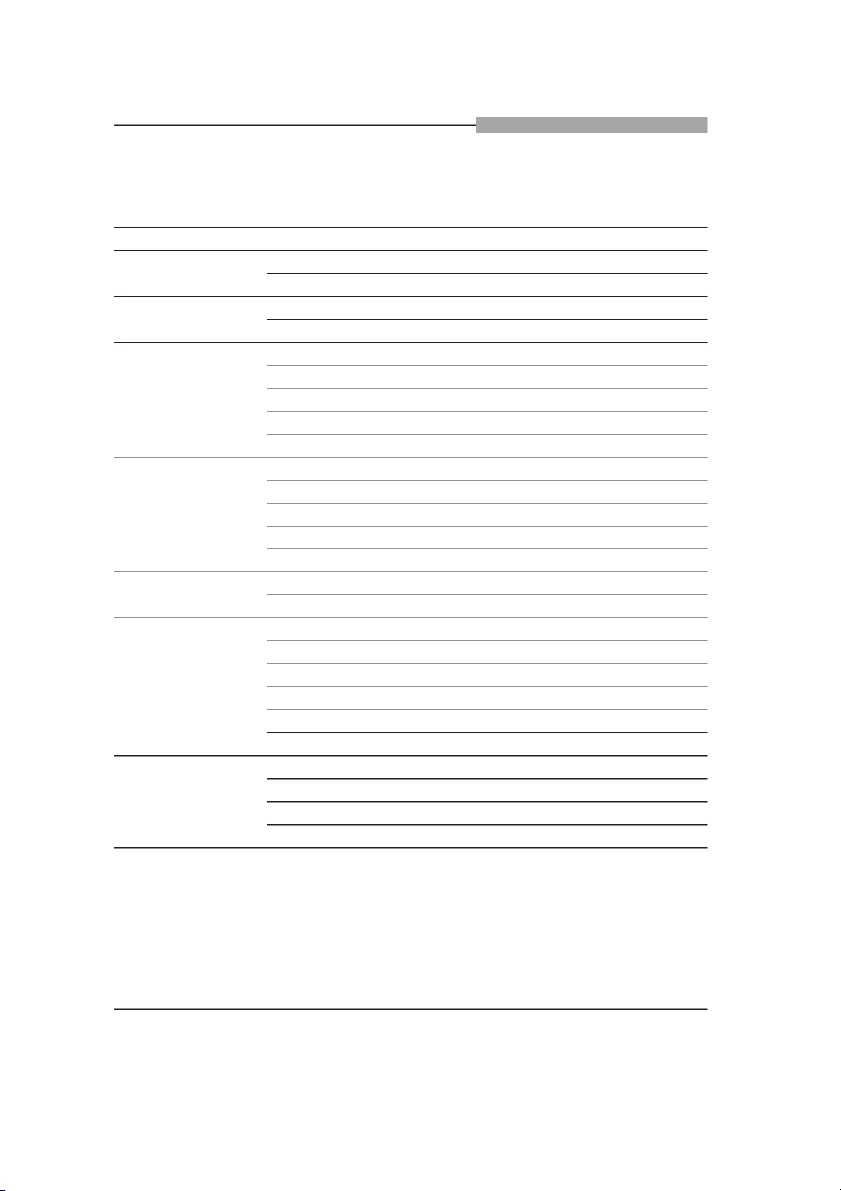

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants (N = 9.781) n Percentage (%) 15 - 18 1.171 12.0 Age 19 - 24 8.610 88.0 Male 4.531 46.3 Sex Female 5.250 53.7 Kinh 9.309 95.2 Ethnicity Other 472 4.8 None 9.270 94.78 Buddhist 202 2.07 Religion Catholic 278 2.84 Christian 17 0.17 Other 14 0.14 Single 7.693 78.65 Married 2.006 20.51 Marital status Divorced/ Separated 36 0.37 Widowed 8 0.08 Other 38 0.39 Rural 4.866 49.75 Living area Urban 4.915 50.25 Elementary 21 0.21 Secondary 413 4.22 High school 2.436 24.91 Education Vocational 380 3.89 College/ University 6.429 65.73 Other 102 1.04 JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022 123 JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH n Percentage (%) High 383 3.92 Middle 8.776 89.72 Household income Near poor 383 3.92 Poor 239 2.44

Table 1 described the sociodemographic

level while the smallest portion of the sample

characteristics of participants in our study

(2.44%) reported the in the low level.

(N=9.781). 88% were between 19 and 24

2. The prevalence of depression and anxiety

years old. The majority of participants were

among young people in Vietnam

female (53.7%). Most were Kinh, the most

2.1 Levels of depression and anxiety

common ethnicity in Vietnam (95.2%). 94.78%

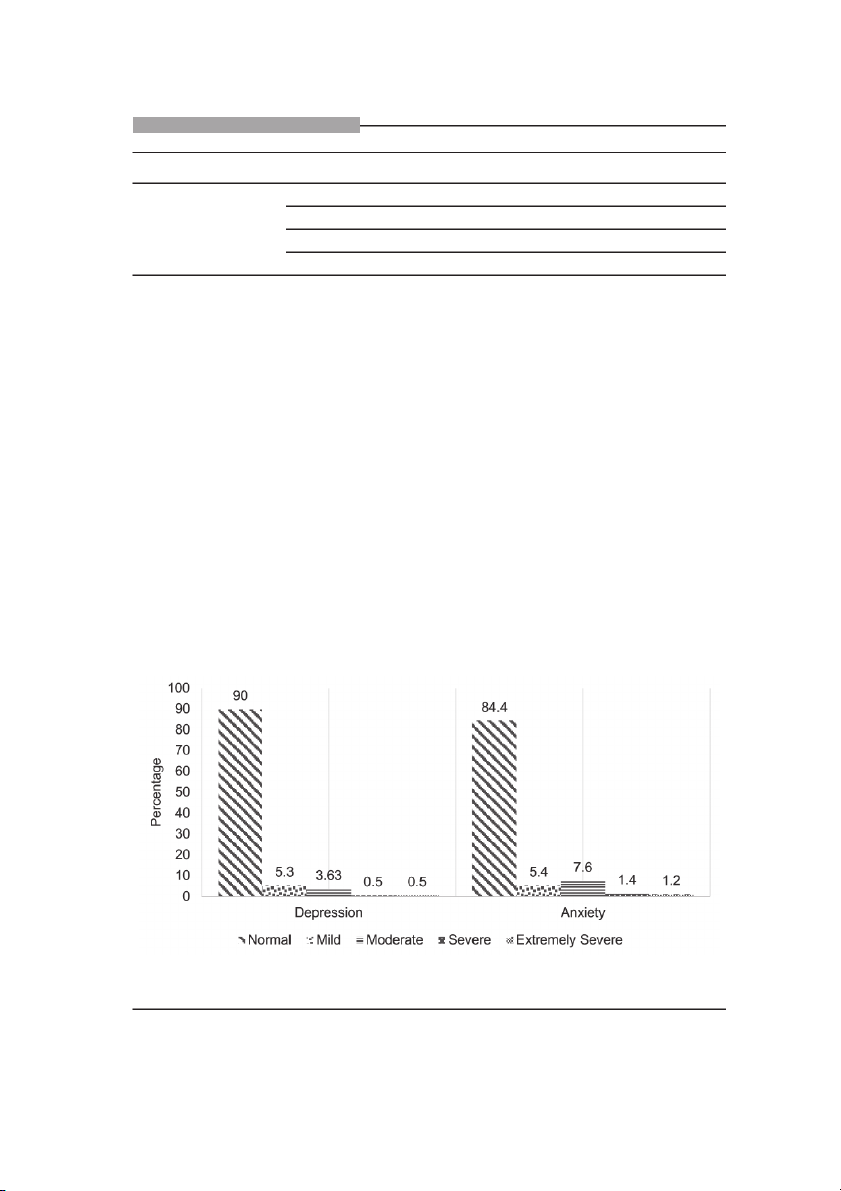

DASS-21 screening results showed that

of participants claimed no religion. Our sample

participants displayed relatively similar levels

included a relatively similar representation

of symptoms of depression (Mean=1.78) and

of Buddhists (2.07%) and Catholics (2.84%).

anxiety (Mean=1.77), suggesting moderate

Most participants reported to be single

severity of both disorders. Figure 1 illustrated

(78.65%). The distribution in terms of living

the prevalence of depression and anxiety

area was split with 49.75% living in rural areas

among young people in Vietnam. 15.6% and

and 50.25% in urban areas. A major portion

10% of participants reported mild to extremely

of our sample reported high education with

severe symptoms of anxiety and depression,

65.73% having graduated from a college or

respectively. Particularly, 1% showed severe

university and 24.91% having graduated from

to extremely severe depression while 2.6%

high school. In terms of household income,

reported severe to extremely severe anxiety.

89.72% of participants reportedin the middle

Figure 1. Levels of depression and anxiety among young people in Vietnam (N=9.781) 124 JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022 JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH

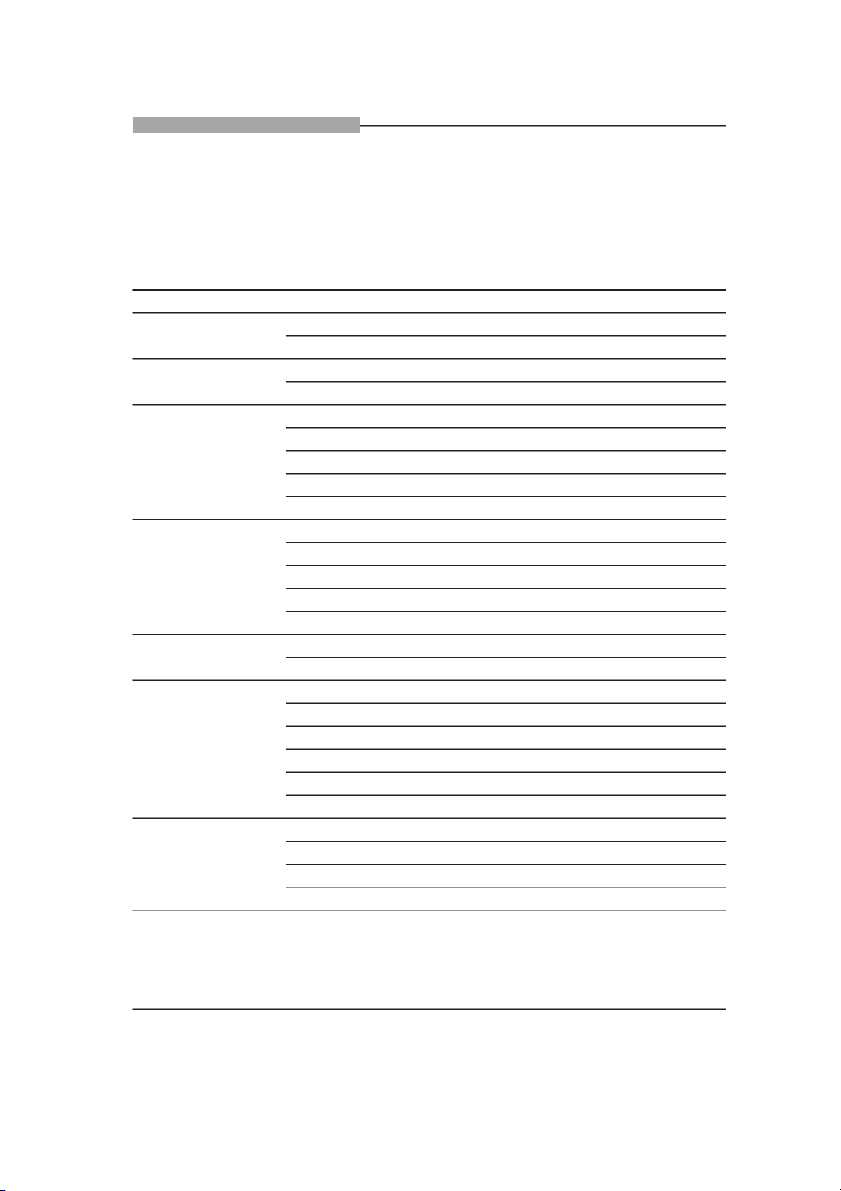

2.2. Factors associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety among young people in Vietnam

Table 2. Factors associated with depressive symptoms (N = 9.781) n OR 95% CI Male 342 1 Sex Female 412 0.98 0.87 - 1.10 Kinh 707 1 Ethnicity Other 47 1.16 0.89 - 1.51 None 699 1 Buddhist 30 1.65 1.16 - 2.35 Religion Catholic 21 1.07 0.75 - 1.52 Christian 4 2.88 1.01 - 8.19 Other 0 1 - Single 645 1 Married 92 0.53 0.45 - 0.64 Marital status Divorced/Separated 5 1.49 0.65 - 3.41 Widowed 2 4.63 1.04 - 20.73 Other 10 2.51 1.24 - 5.09 Rural 337 1 Living area Urban 417 1.27 1.13 - 1.44 Elementary 2 1 Secondary 40 0.96 0.27 - 3.38 High school 191 0.85 0.25 - 2.90 Education Vocational 22 0.71 0.20 - 2.51 College/University 494 0.83 0.24 - 2.83 Other 5 0.57 0.14 - 2.33 High income 26 1 Middle income 611 1.11 0.79 - 1.55 Household income Near low 65 2.77 1.86 - 4.12 Low 52 3.64 2.38 - 5.58

Religion, marital status, living area, and

were 4.63 times more likely to have depression

household income were indicative of depressive

than single people. However, this finding was not

symptoms among young people. Logistic

significant because 95% CI was large, ranging

regression analysis results showed that

from 1.04 – 20.73 and the number of observations

Christians were 2.88 times more likely to have

for this category was small. On the other hand,

depressive symptoms than those with no religion

participants with other marital statuses (e.g., in a

(95% CI: 1.01 – 8.19). Those who are widowed

relationship) were 2.51 times more likely to report JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022 125 JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH

depressive symptoms than single counterparts

having near low and low household income were

(95% CI: 1.24 - 5.09). Additionally, young people

3.64 and 2.77 times, respectively, more likely to

living in urban areas were 1.27 times more likely

report depressive symptoms than those having

to report depressive symptoms than those living

high household income (95% CI: 2.38 - 5.58,

in rural areas (95% CI: 1.13 - 1.44). Also, those 1.86 - 4.12).

Table 3. Factors associated with the prevalence of anxiety (N=9.781) n OR 95% CI Male 733 1 Sex Female 994 1.21 1.08 – 1.34 Kinh 1.626 Ethnicity Other 101 1.29 1.02 – 1.61 None 1.607 1 Buddhist 61 2.06 1.52 – 2.79 Religion Catholic 50 1.04 0.77 – 1.43 Christian 8 4.23 1.63 – 11.0 Other 1 0.37 0.05 – 2.80 Single 1.471 1 Married 234 0.56 0.48 – 0.65 Marital status Divorced/Separated 7 1.02 0.48 – 0.65 Widowed 3 2.54 0.61 – 10.63 Other 12 1.95 0.98 – 3.87 Rural 768 1 Living area Urban 959 1.29 1.16 – 1.43 Elementary 6 1 Secondary 89 0.68 0.26 – 1.82 High school 446 0.56 0.22 – 1.45 Education Vocational 62 0.48 0.18 – 1.30 College/University 1.117 0.52 0.20 – 1.36 Other 7 0.18 0.05 – 0.62 High income 58 1 Middle income 1.490 0.14 0.86 – 1.52 Household income Near low 105 2.11 1.48 – 3.02 Low 74 2.51 1.70 – 3.71

Key indicators of anxiety symptoms among

participants were 1.21 times more likely to report

young people included sex, ethnicity, religion,

anxiety symptoms than male counterparts.

living area, education level, and household

Also, those of ethnic minorities were 1.29 more

income. Our findings suggested that female

likely to report anxiety symptoms than those of 126 JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022 JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH

Kinh (95% CI: 1.24 - 5.09). In addition, religion

addition, sample size can also contribute to

was predictive of young people’s anxiety. In

the mentioned differences. Our large sample

fact, participants following Buddhism were

size (N = 9.781) was much larger than sample

2.06 more likely to report anxiety symptoms

sizes found in domestic and international

than those of no religion (95% CI: 1.24 – 5.09).

studies of the same topic. In addition, different

Participants who were Christian were 4.23 more

use of instrumentation can play a huge role in

likely to report anxiety symptoms than those of

incongruent prevalence rates. While the U.S.

no religion (95% CI: 1.63 -11.0). Those who

study measured the prevalence of depression

were married were twice less likely to report

and anxiety via DSM-IV criteria,19 we utilized

anxiety symptoms than those who were single

DASS-21 criteria instead. Yet, while our

(95% CI: 0.48 – 0.65). Participants residing in

findings did not replicate the prevalence

urban areas were 1.29 times more likely than

rates found in literature, they align with the

counterparts in rural areas (95% CI: 1.16 –

general consensus that the prevalence of

1.43). Additionally, those at higher education

anxiety symptoms is often higher than that of

levels (e.g., some high school, postgraduate) depressive symptoms.

were 0.82 times less likely to report anxiety

In our study, sex was a notable indicator of the

symptoms than those with elementary education

prevalence of anxiety symptoms among young

(95% CI: 1.16 – 1.43). Household income was

people in Vietnam during a COVID-19 outbreak.

also an important indicator of young people’s

In particular, though there was no sex difference

anxiety. Our results suggested that those with

in depression scores, female participants

low or near low household income were 2.11

were 1.21 times more likely to report greater

and 2.51 times, more likely than those with high

anxiety than male counterparts. In fact, the sex

income (95% CI: 1.48 – 3.02 and 1.70 – 3.71).

difference in anxiety symptoms in our study is IV. DISCUSSION

greater than that in a study in China of the same

To our knowledge, this was the first large-

year, which showed that female participants

who were between 12 and 18 years old were

scale study investigating the prevalence of

only 1.15 times more likely to report increased

depression and anxiety symptoms among

anxiety compared to male participants of the

young people in Vietnam, especially during a same age range.2 0 Age range may account for

COVID-19 outbreak. Our results showed that

this discrepancy. While the other study observed

the prevalence among this population was a more restricted age range,2 0 ours included a

15.6% for anxiety and 10% for depression.

broader measure of age (15-24).

Compared to young people in the United

States (14.3% for depression and 31.9%

Religion was also related to anxiety

for anxiety),19 though the prevalence rate

symptoms among young people in Vietnam.

of depressive symptoms in our study was

Our results indicated that, compared to those

relatively similar, anxiety symptoms was

with no religious affiliation, those who were

lower. This discrepancy can be explained by

Buddhist and Christian were at 2.06 times

the differences across samples. While the

and 4.23 times, respectively, greater odds of

U.S. study focused only adolescents aged

displaying anxiety symptoms. A different study

13 to 18,19 our study recruited participants

emphasized the relationship between increased

who were between 15 and 24 years old. In

religious behaviors and reduced depressive JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022 127 JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH

and anxiety symptoms.21 Perhaps, our study

in China found that adolescents living in cities

did not replicate the mental health benefits of

had lower likelihood of reporting increased

religion due to the religious representation in

depressive and anxiety symptoms compared

our sample. While our sample was comprised of

to those living in rural areas (37.7% vs. 47.5%

mostly atheists (94.87%) and some Christians

and 32.5% vs. 40.4%).20 This discrepancy

(0.17%), other study recruited a major portion of

in findings may suggest that the role of living

Christians (73%) and a small portion of atheists

area may vary in prediction of the prevalence of

(11.5%) for their study sample.21

depression and anxiety among young people in

In addition, our study underscored the

Asia during the COVID-19 pandemic.

association between lower household income V. CONCLUSION

and increased depressive and anxiety

symptoms. Compared to those with high

Our study described the prevalence of

household income, young people with low

depressive and anxiety symptoms among

or near low household income were at 3.64

young people aged 15 to 24 in Vietnam during

times and 2.77 times, respectively, of reporting

the COVID-19 pandemic. We highlighted

depressive symptoms. For anxiety symptoms,

the correlation between sociodemographic

those with near p low and near low household variables and depressive and anxiety

income were 2.51 times and 2.11 times,

symptoms. Religion, other marital status,

respectively, more likely to report higher scores

metropolitan living, and near low or low

than those with high-tier household income.

household income were all related to young

According to a large study in Germany of 1586

people’s elevated depression. Also, we found

young people aged 7 to 18, low household

a positive relationship between female sex,

income was linked to migration background,

minority ethnicity, Buddhism, Christianity,

limited living space, and increased mental

single status, metropolitan living, elementary

health problems.22 Evidence in a different study

education level, near p low or low household

on young people’s mental problems during the

income and greater anxiety symptoms.

Such findings emphasize the needs for

COVID-19 pandemic suggests similar trends.23

As our findings support current literature, we implementing effective mental health

speculate that the relationship between family

interventions for Vietnamese young people

income and the prevalence of depressive and

enduring many COVID-19-related impacts.

Specifically, we recommended to develop

anxiety symptoms among young people during

the COVID-19 pandemic can be universal.

early intervention programs which target

young people who exhibit mild to extremely

Lastly, living area was also associated with

severe depression and anxiety with eclectic

how common depressive and anxiety symptoms

outlets for mental health care. Additionally,

were among the young population in Vietnam. further research, particular longitudinal

Our results indicated those who lived in cities

research should be conducted to investigate

were at 1.27 greater odds for reporting more

other social determinants of the prevalence

depression symptoms than those who lived in

of depression and anxiety, as well as stress,

rural areas. Similarly, compared to those in rural

and to examine the trends of depression and

areas, city dwellers were 1.29 times more likely

anxiety prevalence among young people over

to score higher in anxiety symptoms. A study

various COVID-19 waves in Vietnam. 128 JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022 JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH REFERENCE

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Ngày

8. World Health Organization (WHO).

sức khoẻ tâm thần thế giới - một căn bệnh tiềm

Caring for children and adolescents with mental

ẩn. World Health Organization. https://www.who.

disorders: setting WHO directions. World Health

int/vietnam/vi/news/detail/09-10-2008-world-

Organization; 2003. https://apps.who.int/iris/

mental-health-day-a-hidden-illness. Published

handle/10665/42679. Accessed March 4, 2022.

October 9, 2008. Accessed March 6, 2022.

9. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O,

2. Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating

et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset

the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet

distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National

Psychiatry. 2016; 3(2): 171-178. doi:10.1016/

Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen S2215-0366(15)00505-2.

Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6): 593-602. doi:10.1001/

3. James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. archpsyc.62.6.593.

Global, regional, and national incidence,

10. Vahratian A, Blumberg SJ, Terlizzi

prevalence, and years lived with disability for

EP, et al. Symptoms of anxiety or depressive

354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and

disorder and use of mental health care among

territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis

adults during the COVID-19 pandemic - United

for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.

States, August 2020-February 2021. MMWR

The Lancet. 2018; 392(10159): 1789-1858.

Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021; 70(13): 490-494.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e2.

4. Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, et

11. Le HT, Lai AJX, Sun J, et al. Anxiety and

al. Mental Health Surveillance Among Children

depression among people under the Nationwide

- United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Suppl.

Partial Lockdown in Vietnam [published

2022; 71(2): 1-42. Published 2022 Feb 25.

correction appears in Front Public Health. 2021 doi:10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1.

May 24;9:692085]. Front Public Health. 2020;

5. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ,

8: 589359. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.589359.

et al. Prevalence and Treatment of Depression,

12. Ngoc Cong Duong K, Nguyen Le Bao

Anxiety, and Conduct Problems in US Children.

T, Thi Lan Nguyen P, et al. Psychological

J Pediatr. 2019; 206: 256-267.e3. doi:10.1016/j.

impacts of COVID-19 during the first nationwide jpeds.2018.09.021.

lockdown in Vietnam: web-based, cross-

6.Mental Health Foundation. Children and

sectional survey study [published correction

young people. Mental Health Foundation.

appears in JMIR Form Res. 2021 Mar 5; 5(3):

https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/c/

e28357]. JMIR Form Res. 2020; 4(12): e24776.

children-and-young-people. Published August doi:10.2196/24776.

7, 2015. Accessed March 4, 2022.

13. Porter C, Favara M, Hittmeyer A, et al.

7. Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, et al.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety

Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder

and depression symptoms of young people in

indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a

the global south: evidence from a four-country

nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017.

cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021; 11(4): e049653.

J Abnorm Psychol. 2019; 128(3): 185-199.

doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049653. doi:10.1037/abn0000410.

14. World Health Organization (WHO). JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022 129 JOURAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH

Adolescent mental health. World Health

e0180557. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180557.

Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/

19. Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et

fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in

Published November 17, 2021. Accessed

U.S. adolescents: results from the National March 6, 2022. Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent

15. Tran TD, Tran T, Fisher J. Validation of

Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc

the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) 21

Psychiatry. 2010; 49(10): 980-989. doi:10.1016/j.

as a screening instrument for depression and jaac.2010.05.017.

anxiety in a rural community-based cohort of

20. Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, et al.

northern Vietnamese women. BMC Psychiatry.

Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates

2013; 13(1): 24. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-24.

of psychological health problems in Chinese

16. Bartlett EJ, Kotrlik WJ, Higgins CC.

adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Organizational Research: determining

Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020; 29(6): 749-

appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf

758. doi:10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4.

Technol Learn Perform J. 2001;19:1. https://

21. Schapman AM, Inderbitzen-Nolan HM.

www.opalco.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/

The role of religious behaviour in adolescent

Reading-Sample-Size1.pdf. Accessed March

depressive and anxious symptomatology. J 4, 2022.

Adolesc. 2002; 25(6): 631-643. doi:10.1006/ 17. COVID-19 Mental Disorders jado.2002.0510. Collaborators. Global prevalence and

22. Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart

burden of depressive and anxiety disorders

M, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on

in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due

quality of life and mental health in children and

to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;

adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc

398(10312): 1700-1712. doi:10.1016/S0140-

Psychiatry. doi:10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5. 6736(21)02143-7.

23. Guessoum SB, Lachal J, Radjack R, et

18. Le MTH, Tran TD, Holton S, et al.

al. Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the

Reliability, convergent validity and factor structure

COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry

of the DASS-21 in a sample of Vietnamese

Res. 2020; 291: 113264. doi:10.1016/j. adolescents. PLOS ONE. 2017; 12(7): psychres.2020.113264. 130 JMR 154 E10 (6) - 2022