Preview text:

Chapter 2: Comparative Advantage EXCHANGE AND OPPORTUNITY COST

Absolute advantage: one person has an absolute advantage over another if he or she

takes fewer hours to perform a task than the other person.

Comparative advantage: one person has a comparative advantage over another if his

or her opportunity cost of performing a task is lower than the other person’s opportunity cost

Example 2.1: Scarcity Principle

Kelly Wearstler is among the most famous and influential interior designers in the

United States today. She has received numerous accolades for her commercial and residential

design work, has completed projects for top celebrities such as Cameron Diaz, Gwen Stefani,

and Ben Stiller, and boasts more than 700,000 followers on Instagram.

Although Kelly devotes most of her time and talent to interior design, she is well

equipped to do a broad range of other design work. Suppose Kelly could design her own web

page in 300 hours, half the time it would take any other web designer. Does that mean that

Kelly should design her own web page?

Suppose that on the strength of her talents as an interior designer, Kelly earns more

than $1 million a year, implying that the opportunity cost of any time she spent designing her

web page would be over $500 per hour. Kelly would have little difficulty engaging a highly

qualified web designer whose hourly wage is considerably less than $500 per hour. So even

though Kelly’s substantial skills might enable her to design her web page more quickly than

most web designers, it would not be in her interest to do so.

THE PRINCIPLE OF COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

Example 2.2: Comparative Advantage

Should Ana update her own web page?

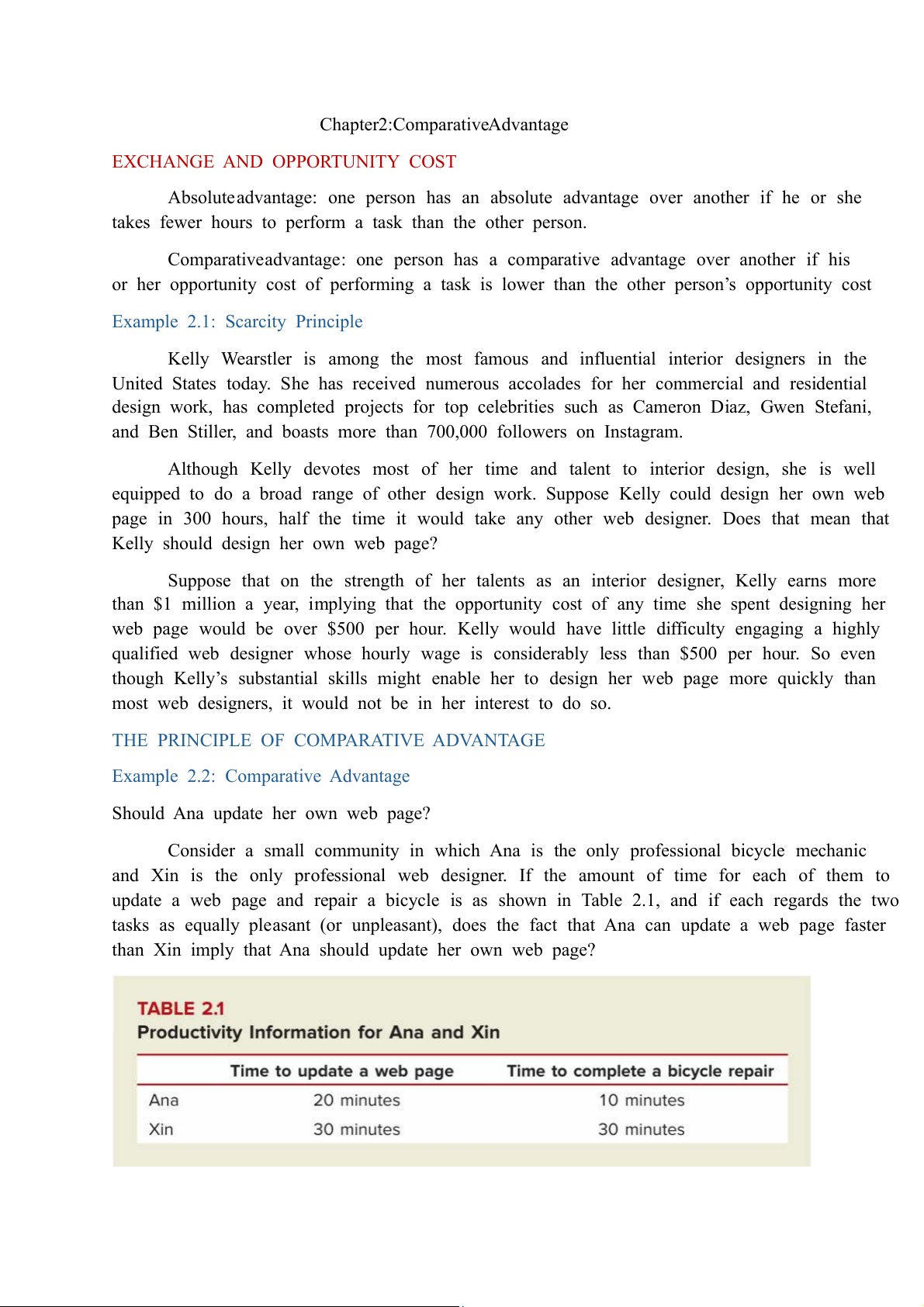

Consider a small community in which Ana is the only professional bicycle mechanic

and Xin is the only professional web designer. If the amount of time for each of them to

update a web page and repair a bicycle is as shown in Table 2.1, and if each regards the two

tasks as equally pleasant (or unpleasant), does the fact that Ana can update a web page faster

than Xin imply that Ana should update her own web page?

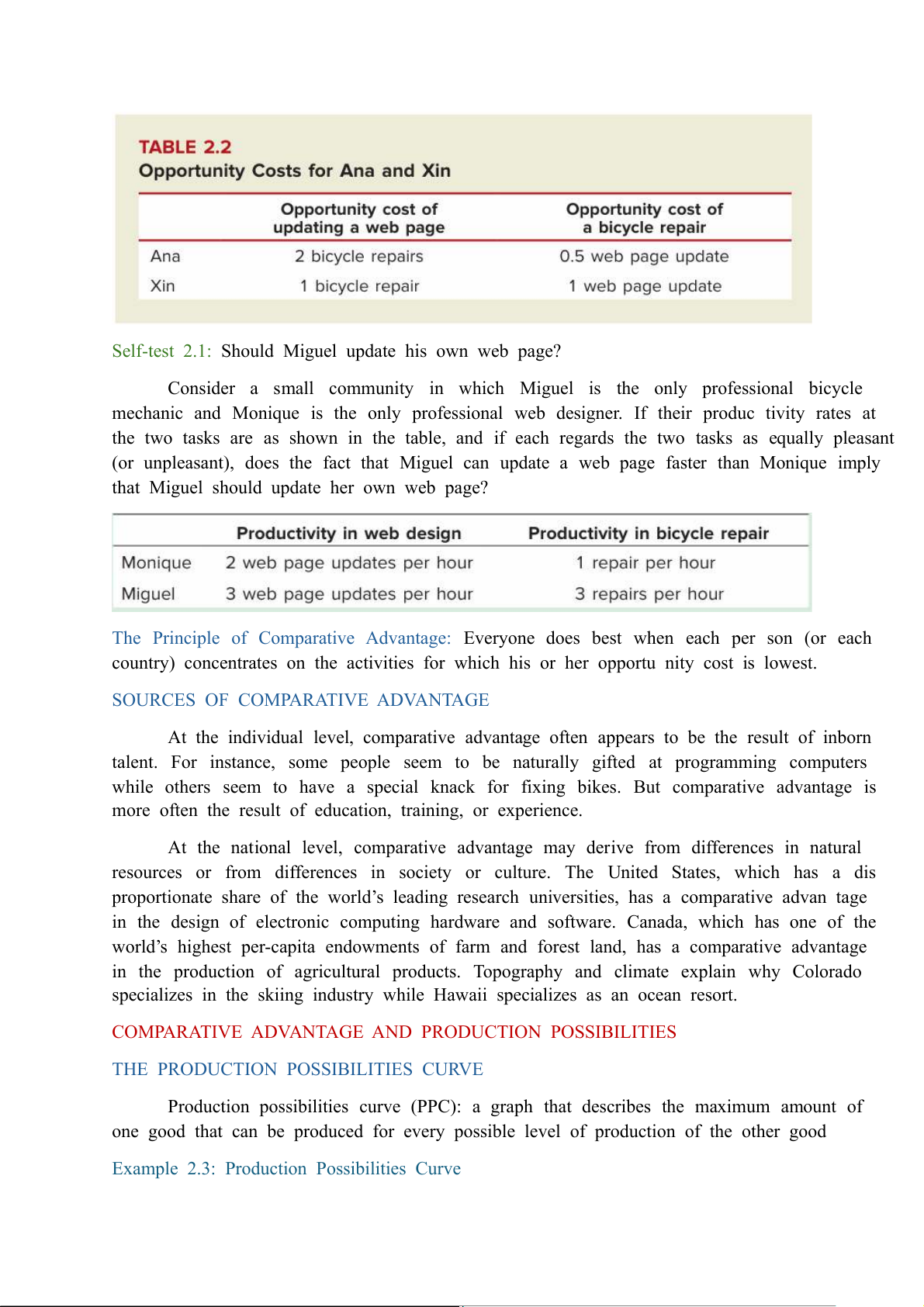

Self-test 2.1: Should Miguel update his own web page?

Consider a small community in which Miguel is the only professional bicycle

mechanic and Monique is the only professional web designer. If their produc tivity rates at

the two tasks are as shown in the table, and if each regards the two tasks as equally pleasant

(or unpleasant), does the fact that Miguel can update a web page faster than Monique imply

that Miguel should update her own web page?

The Principle of Comparative Advantage: Everyone does best when each per son (or each

country) concentrates on the activities for which his or her opportu nity cost is lowest.

SOURCES OF COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

At the individual level, comparative advantage often appears to be the result of inborn

talent. For instance, some people seem to be naturally gifted at programming computers

while others seem to have a special knack for fixing bikes. But comparative advantage is

more often the result of education, training, or experience.

At the national level, comparative advantage may derive from differences in natural

resources or from differences in society or culture. The United States, which has a dis

proportionate share of the world’s leading research universities, has a comparative advan tage

in the design of electronic computing hardware and software. Canada, which has one of the

world’s highest per-capita endowments of farm and forest land, has a comparative advantage

in the production of agricultural products. Topography and climate explain why Colorado

specializes in the skiing industry while Hawaii specializes as an ocean resort.

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE AND PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES

THE PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES CURVE

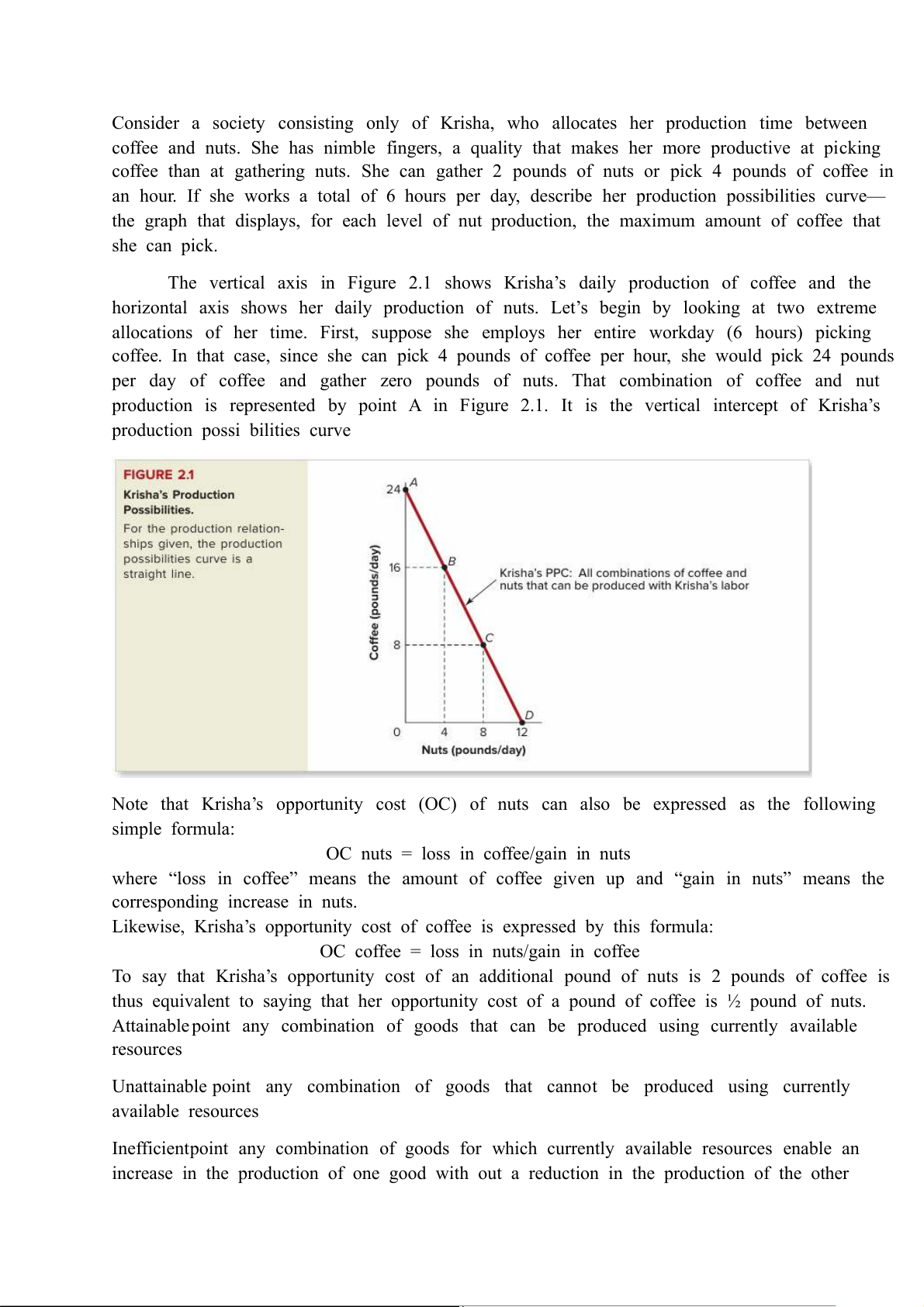

Production possibilities curve (PPC): a graph that describes the maximum amount of

one good that can be produced for every possible level of production of the other good

Example 2.3: Production Possibilities Curve

Consider a society consisting only of Krisha, who allocates her production time between

coffee and nuts. She has nimble fingers, a quality that makes her more productive at picking

coffee than at gathering nuts. She can gather 2 pounds of nuts or pick 4 pounds of coffee in

an hour. If she works a total of 6 hours per day, describe her production possibilities curve—

the graph that displays, for each level of nut production, the maximum amount of coffee that she can pick.

The vertical axis in Figure 2.1 shows Krisha’s daily production of coffee and the

horizontal axis shows her daily production of nuts. Let’s begin by looking at two extreme

allocations of her time. First, suppose she employs her entire workday (6 hours) picking

coffee. In that case, since she can pick 4 pounds of coffee per hour, she would pick 24 pounds

per day of coffee and gather zero pounds of nuts. That combination of coffee and nut

production is represented by point A in Figure 2.1. It is the vertical intercept of Krisha’s

production possi bilities curve

Note that Krisha’s opportunity cost (OC) of nuts can also be expressed as the following simple formula:

OC nuts = loss in coffee/gain in nuts

where “loss in coffee” means the amount of coffee given up and “gain in nuts” means the

corresponding increase in nuts.

Likewise, Krisha’s opportunity cost of coffee is expressed by this formula:

OC coffee = loss in nuts/gain in coffee

To say that Krisha’s opportunity cost of an additional pound of nuts is 2 pounds of coffee is

thus equivalent to saying that her opportunity cost of a pound of coffee is ½ pound of nuts.

Attainable point any combination of goods that can be produced using currently available resources

Unattainable point any combination of goods that cannot be produced using currently available resources

Inefficient point any combination of goods for which currently available resources enable an

increase in the production of one good with out a reduction in the production of the other

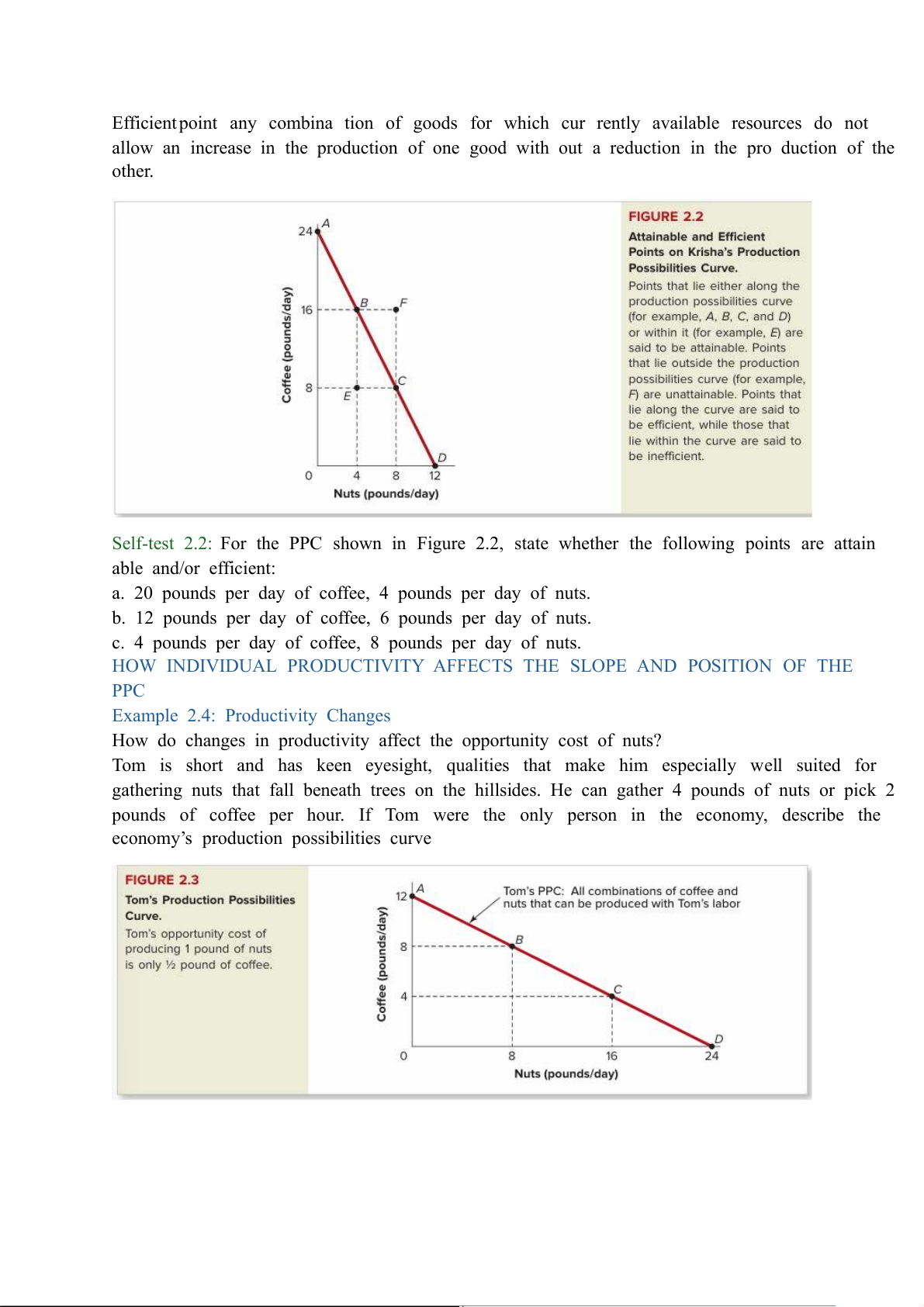

Efficient point any combina tion of goods for which cur rently available resources do not

allow an increase in the production of one good with out a reduction in the pro duction of the other.

Self-test 2.2: For the PPC shown in Figure 2.2, state whether the following points are attain able and/or efficient:

a. 20 pounds per day of coffee, 4 pounds per day of nuts.

b. 12 pounds per day of coffee, 6 pounds per day of nuts.

c. 4 pounds per day of coffee, 8 pounds per day of nuts.

HOW INDIVIDUAL PRODUCTIVITY AFFECTS THE SLOPE AND POSITION OF THE PPC

Example 2.4: Productivity Changes

How do changes in productivity affect the opportunity cost of nuts?

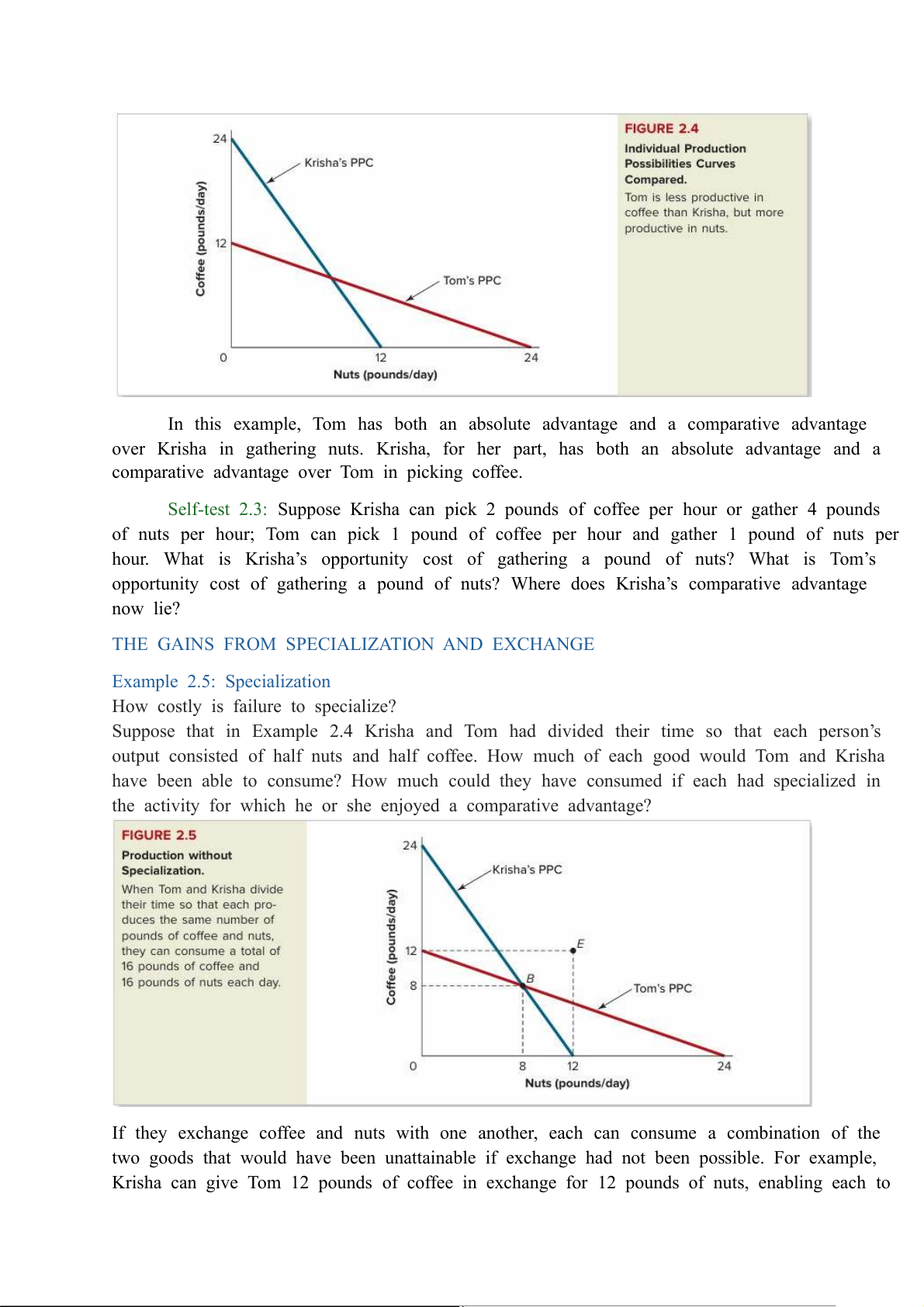

Tom is short and has keen eyesight, qualities that make him especially well suited for

gathering nuts that fall beneath trees on the hillsides. He can gather 4 pounds of nuts or pick 2

pounds of coffee per hour. If Tom were the only person in the economy, describe the

economy’s production possibilities curve

In this example, Tom has both an absolute advantage and a comparative advantage

over Krisha in gathering nuts. Krisha, for her part, has both an absolute advantage and a

comparative advantage over Tom in picking coffee.

Self-test 2.3: Suppose Krisha can pick 2 pounds of coffee per hour or gather 4 pounds

of nuts per hour; Tom can pick 1 pound of coffee per hour and gather 1 pound of nuts per

hour. What is Krisha’s opportunity cost of gathering a pound of nuts? What is Tom’s

opportunity cost of gathering a pound of nuts? Where does Krisha’s comparative advantage now lie?

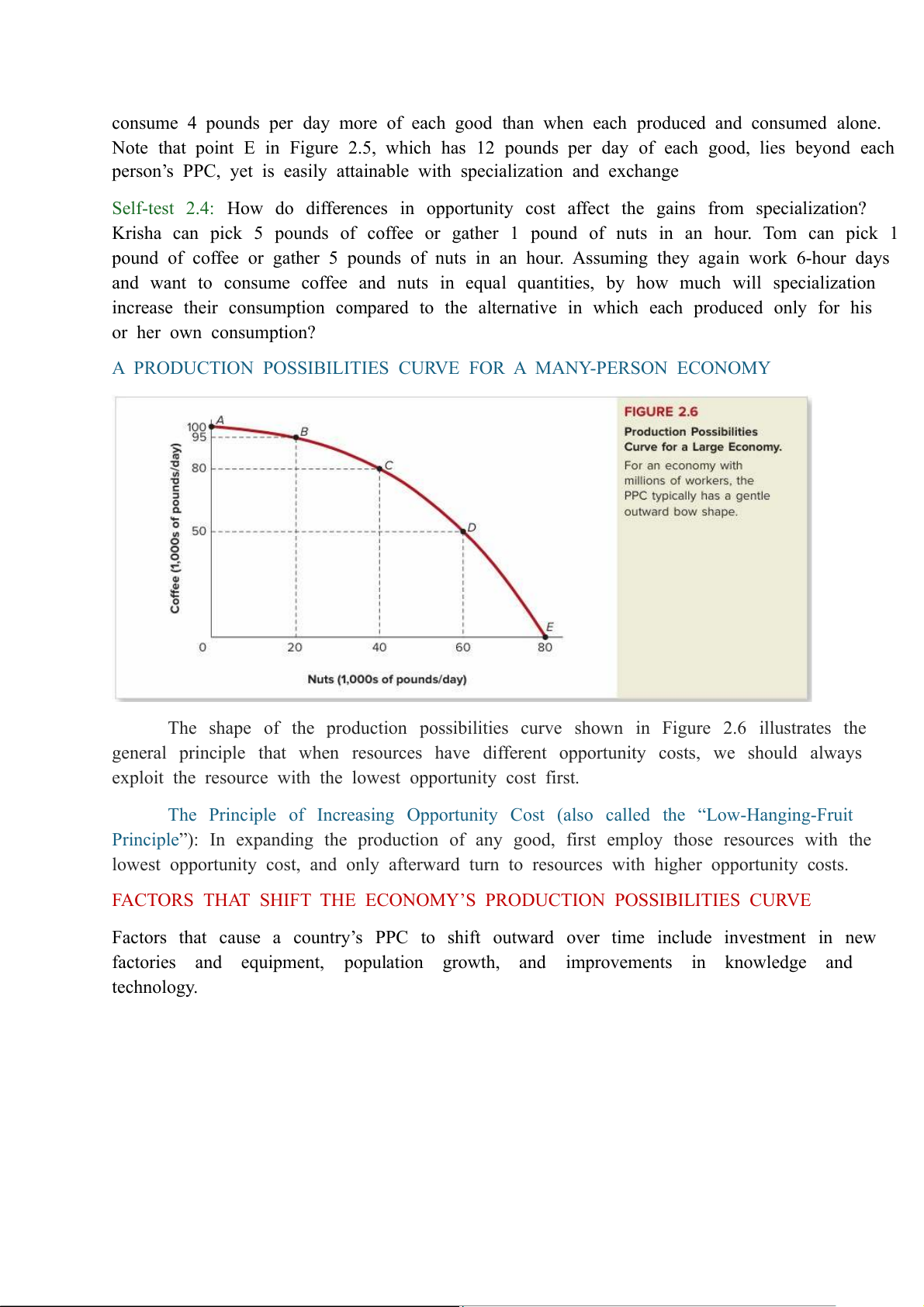

THE GAINS FROM SPECIALIZATION AND EXCHANGE Example 2.5: Specialization

How costly is failure to specialize?

Suppose that in Example 2.4 Krisha and Tom had divided their time so that each person’s

output consisted of half nuts and half coffee. How much of each good would Tom and Krisha

have been able to consume? How much could they have consumed if each had specialized in

the activity for which he or she enjoyed a comparative advantage?

If they exchange coffee and nuts with one another, each can consume a combination of the

two goods that would have been unattainable if exchange had not been possible. For example,

Krisha can give Tom 12 pounds of coffee in exchange for 12 pounds of nuts, enabling each to

consume 4 pounds per day more of each good than when each produced and consumed alone.

Note that point E in Figure 2.5, which has 12 pounds per day of each good, lies beyond each

person’s PPC, yet is easily attainable with specialization and exchange

Self-test 2.4: How do differences in opportunity cost affect the gains from specialization?

Krisha can pick 5 pounds of coffee or gather 1 pound of nuts in an hour. Tom can pick 1

pound of coffee or gather 5 pounds of nuts in an hour. Assuming they again work 6-hour days

and want to consume coffee and nuts in equal quantities, by how much will specialization

increase their consumption compared to the alternative in which each produced only for his or her own consumption?

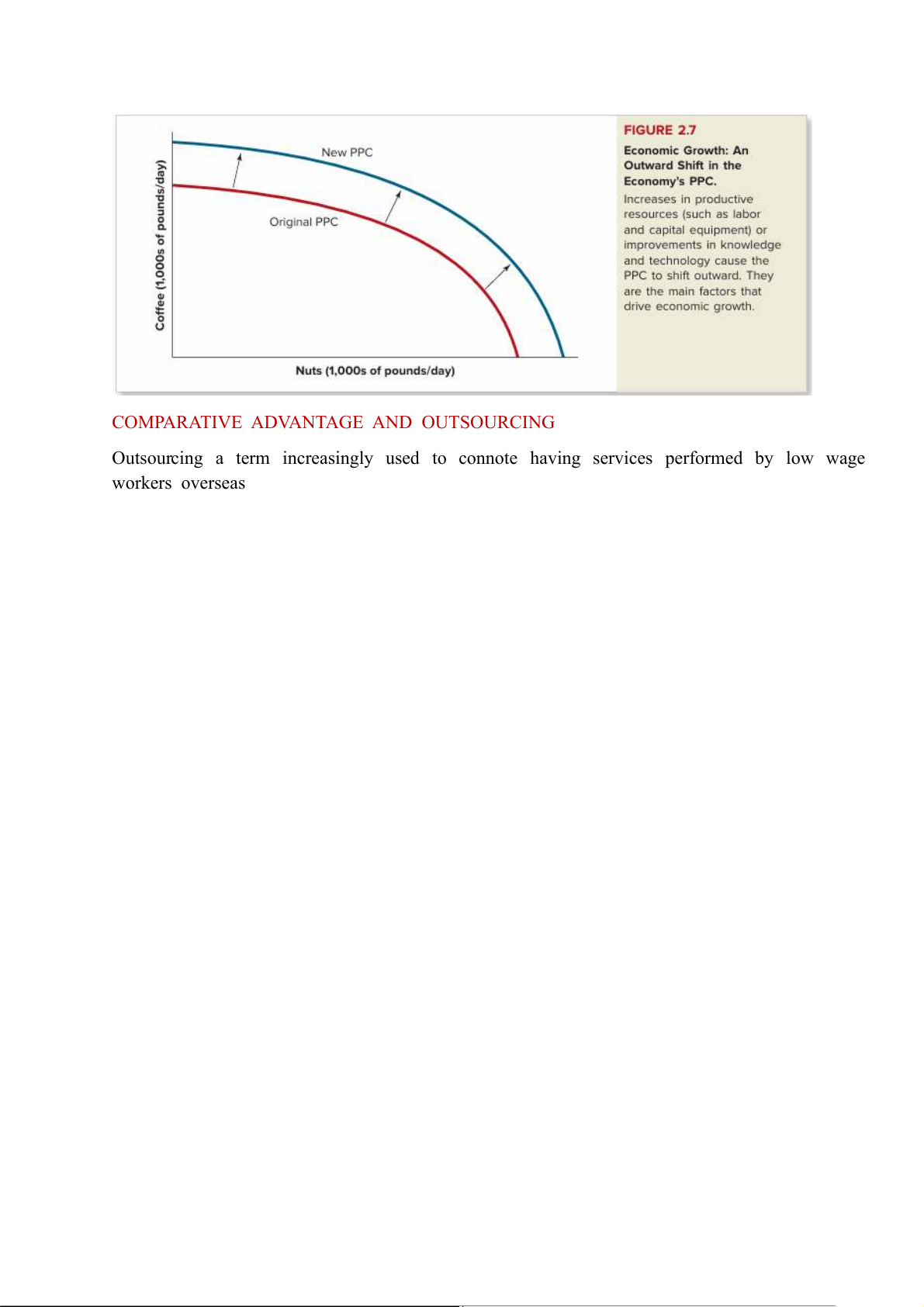

A PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES CURVE FOR A MANY-PERSON ECONOMY

The shape of the production possibilities curve shown in Figure 2.6 illustrates the

general principle that when resources have different opportunity costs, we should always

exploit the resource with the lowest opportunity cost first.

The Principle of Increasing Opportunity Cost (also called the “Low-Hanging-Fruit

Principle”): In expanding the production of any good, first employ those resources with the

lowest opportunity cost, and only afterward turn to resources with higher opportunity costs.

FACTORS THAT SHIFT THE ECONOMY’S PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES CURVE

Factors that cause a country’s PPC to shift outward over time include investment in new

factories and equipment, population growth, and improvements in knowledge and technology.

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE AND OUTSOURCING

Outsourcing a term increasingly used to connote having services performed by low wage workers overseas