Preview text:

11 OCTOBER 2010

Scientific Background on the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2010 MARKETS WITH SEARCH FRICTIONS

compiled by the Economic Sciences Prize Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

THE ROYAL SWEDISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES has as its aim to promote the sciences and strengthen their influence in society.

BOX 50005 (LILLA FRESCATIVÄGEN 4 A), SE-104 05 STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN

TEL +46 8 673 95 00, FAX +46 8 15 56 70, INFO@KVA.SE HTTP://KVA.SE MarketswithSearchFrictions 1 Introduction

Mostreal-worldtransactionsinvolvevariousformsofimpedimentstotrade,

or“frictions”. Buyersmayhavetrouble ndingthegoodstheyarelooking

forandsellersmaynotbeableto ndbuyersforthegoodstheyhaveto

offer. These frictions can take many forms and may have many sources,

including worker and rm heterogeneity, imperfect information, and costs

oftransportation. Howaremarketoutcomesin uencedbysuchfrictions?

Thatis,howshouldweexpectpricestoformand–giventhatmarketswill

notclear atallpointsintime–howarequantitiesdetermined? Dothese

frictions motivate government intervention? These questions are perhaps

particularlypertinentinthelabormarketwherecostlyandtime-consuming

transactionsarepervasiveandwherethequantitydeterminationmayresult

inunemployment: someworkerswillnot ndjobopeningsortheirapplica-

tionswillbeturneddowninfavorof otherworkers.

This year’s Prize is awarded for fundamental contributions to search

andmatchingtheory. Thistheoryoffersaframeworkforstudyingfrictions

in real-world transactions and has led to new insights into the workings

ofmarkets. Thedevelopmentofequilibriummodelsfeaturingsearchand

matchingstartedintheearly1970sandhassubsequentlydevelopedintoa

verylargeliterature. ThePrizeisgrantedforthecloselyrelatedcontribu-

tionsmadeby PeterDiamond,DaleMortensen,andChristopherPissarides.

Thesecontributionsincludetheanalysisofpricedispersionandefficiencyin

economieswithsearchandmatchingfrictionsaswellasthedevelopmentof

whathascometobeknownasthemodernsearchandmatchingtheoryof unemployment.

TheresearchofDiamond,MortensenandPissaridesfocusesonspeci c

frictionsduetocostlysearchandpairwisematching,i.e.,theexplicitdiffi-

cultiesbuyersandsellershaveinlocatingeachother,therebyresultingin

failure of markets to clear at all points in time. Buyers and sellers face

costsintheirattemptstolocateeachother(“search”)andmeetpairwise 1

whentheycomeintocontact(“matching”). Incontrast,standardmarket

descriptionsinvolvealargenumberofparticipantswhotradeatthesame

time. Accessto thismarketplaceandalltherelevantinformationaboutit

iscostlesslyavailabletoalleconomicagents;inparticular,alltraderswould

tradeatthesamemarketprice. Oneofthemainissues,therefore,ishow

priceformationworksinamarketwithsearchfrictions. Inparticular,how

much price dispersion will be observed, and how large are the deviations fromcompetitivepricing?

PeterDiamondaddressedthesequestionsinanimportantpaperfrom

1971,whereheshowed, rst,thatthemerepresenceofcostlysearchand

matchingfrictionsdoesnotsufficetogenerateequilibriumpricedispersion.

Second,andmorestrikingly,Diamondfoundthatevenaminutesearch cost

movestheequilibriumpriceveryfar fromthecompetitiveprice: heshowed

thattheonlyequilibrium outcomeisthemonopolyprice. Thissurprising

ndinghasbeenlabeledthe“Diamondparadox”andgeneratedmuchfollow- upresearch.

Anotherimportantissueinsearchmarketsiswhetherthereistoomuch

ortoolittlesearch, i.e.,whetherornotthemarketsdeliverefficientoutcomes.

Sincetherewillbeunexecutedtradeandunemployedresources–buyerswho

havenotmanagedtolocatesellers,andviceversa–theoutcomemightbe

regardedasnecessarilyinefficient. However,theappropriatecomparisonis

notwithaneconomywithoutfrictions. Giventhatthefrictionisafunda-

mentalonethattheeconomycannotavoid,therelevantissueiswhetherthe

economyisconstrainedefficient,i.e., deliversthebestoutcomegiventhis

restriction. Itshouldalsobenotedthataggregatewelfareisnotnecessarily

higherwithmoresearchsincesearchiscostly. Diamond, Mortensen,and

Pissarides all contributed important insights into the efficiency question,

withthe rstresultsappearinginthelate1970sandearly1980s(Diamond

and Maskin, 1979, 1981; Diamond 1982a; Mortensen, 1982a,b; Pissarides

1984a,b). Agenericresultisthatefficiencycannotbeexpectedandpolicy

interventionsmaythereforebecomedesirable.

Alongsimilarlines,Diamondarguedthatasearchandmatchingenvi-

ronmentcanleadtomacroeconomicunemploymentproblemsasaresultof

thedifficultiesincoordinatingtrade. Thisargumentwasintroducedina

highlyin uentialpaper,Diamond(1982b),whereamodelfeaturingmulti-

plesteady-stateequilibriaisdeveloped. Theanalysisprovidesarationale

for “aggregate demand management” so as to steer the economy towards

thebestequilibrium. Thekeyunderlyingthisresultisasearchexternality,

wherebyasearchingworkerdoesnotinternalizeallthebene tsandcosts

toothersearchers. ThemodelDiamonddevelopedinthiscontexthasalso 2

become a starting point for strands of literature in applied areas such as

monetary economicsandhousing,whichfeaturespeci ckindsofexchange

thatareusefullystudiedwithDiamond’ssearchandmatchingmodel.

Theresearchonsearchandmatchingtheorythusraisesgeneralandim-

portantquestionsrelevantformanyappliedcontexts. However,thetheory

hasbyfarhaditsdeepestimpactswithinlaboreconomics. Thequestion

ofwhyunemployment existsandwhatcanandshouldbedoneaboutitis

oneofthemostcentralissuesineconomics. Labormarketsdonotappear

to“clear”: therearejoblessworkerswhosearchforwork(unemployment)

and rms that look for workers (vacancies). It has proven to be a diffi-

cultchallengetoformulateafullyspeci edequilibriummodelthatgener-

atesbothunemploymentandvacancies. TheresearchbyPeterDiamond,

Dale Mortensen and Christopher Pissarides has fundamentally in uenced

ourviewsonthedeterminantsofunemploymentand,moregenerally,onthe

workingsoflabormarkets. Akeycontributionisthedevelopmentofanew

frameworkforanalyzinglabormarketsforbothpositiveandnormativepur-

posesinadynamicgeneralequilibriumsetting. Theresultingclassofmodels

hasbecomeknownastheDiamond-Mortensen-Pissaridesmodel(orDMP

model). This canonical model originated in the rst search-matching in-

sightsfromthe1970salthoughthecrucialdevelopmentsoccurredlateron.

Especially important contributions were Mortensen and Pissarides (1994)

and Pissarides (1985). The DMP model allows us to consider simultane-

ously(i)howworkersand rmsjointlydecidewhethertomatchortokeep

searching;(ii)in caseofacontinuedmatch,howthebene tsfrom the match

aresplitintoawagefortheworkerandapro tforthe rm;(iii) rmentry,

i.e., rms’decisionsto“createjobs”;and(iv)howthematchofaworkerand

a rmmightdevelopovertime,possiblyleadingtoagreed-uponseparation.

Theresultingmodelsandtheirfurtherdevelopmentswerequiterichand

theappliedresearchonlabormarkets,boththeoreticalandempirical,has

ourished. Theoreticalworkhasincludedpolicyanalysis,bothpositiveand

normative. Itwasnowstraightforwardtoexaminetheeffectsofpoliciescon-

cerning hiringcosts, ringcosts,minimumwagelaws,taxes,unemployment

bene ts,etc. onunemploymentandeconomicwelfare. Empiricalworkhas

consistedofsystematicwaysofevaluatingthesearchandmatchingmodel

using aggregate data on vacancies and unemployment, including the de-

velopmentofdatabasesandanalysesoflabormarket ows, i.e., owsof

workersbetweendifferentlabor-marketactivitiesaswellasjobcreationand jobdestruction ows.

TheDMPmodelhasalsobeenusedtoanalyzehowaggregateshocks

are transmitted to the labor market and lead to cyclical uctuations in 3

unemployment, vacancies, and employment ows. The rst step towards

a coherent search-theoretical analysis of the dynamics of unemployment,

vacanciesandrealwageswastakenbyPissarides(1985).

Applications of search and matching theory extend well beyond labor

markets. The theory has been used to study issues in consumer theory,

monetary theory, industrial organization, public economics, nancial eco-

nomics,housingeconomics,urbaneconomicsandfamilyeconomics.

2 Generalaspectsofsearchandmatchingmarkets

The broad theoretical work on search and matching addresses three fun-

damentalquestions. The rstispricedispersion; i.e., whetherthelawof

onepriceshouldbeexpectedtoholdinmarketswithfrictions. Acentral

resulthereistheDiamondparadoxandthesubsequentattemptstoresolve

it. The second issue concerns efficiency, which began to be addressed in

thelate1970sandintothenextdecade. Thethirdquestionfocusesonthe

possibility ofcoordinationfailuresbasedonthestylizedmodelinDiamond (1982b). 2.1 Priceformation

The rststrandofmodelswithexplicitsearchactivityhadanentirelymi-

croeconomicfocusandexaminedworkers’orconsumers’optimalsearchbe-

haviorunderimperfectinformationaboutwagesorprices. Importantearly

contributions to this microeconomic literature include McCall (1970) and

Mortensen(1970a,b). Thesemodelsgeneratednewresultsregardingthede-

terminantsofsearchactivityand,inparticular,thedurationofunemploy-

ment. Theproblemaddressedintheprototypemicroeconomicjobsearch

modelconcernstheoptimalruleforacceptingjoboffers. Theunemployed

worker searching for employment is portrayed as unaware of wage offers

availableatsingle rmsbutawareofthedistributionofwageoffersacross

rms. Theworkeristhenenvisionedassamplingwageofferssequentially

andattemptingtomaximizetheexpectedpresentvalueoffutureincome.

Optimalsearchbehaviorinvolvesareservationwage,atwhichtheworkeris

indifferentbetweenacceptingajobandremainingunemployed. Thereser-

vationwageisthussetsoastoequatethevalueofunemployment,whose

immediatereturnisanyunemploymentbene ttheworkerreceives,tothe

present discounted value of future wage incomes from this job, which in-

volvesthelikelihoodofkeepingthejob,theinterestratebywhichthefu-

tureearningsarediscounted,andanyexpectedwagemovementsonthejob. 4

Afundamentalquestionleftunansweredintheearlymicroliteraturewas

whetherthepostulateddistributionofprices, orwages, couldberationalized asanequilibriumoutcome.

Diamond’s (1971) article “A Model of Price Adjustment” established

whatcametobeknownastheDiamondparadox. Hedemonstrated, surpris-

ingly,thatunderrathergeneralconditionsinanenvironmentwherebuyers

andsellerssearchforeachother,andwherethe sellersset,i.e.,committo,

prices in advance of meeting customers, the single monopoly price would

prevail. Diamondarguedthat,evenwithveryminorsearchcostsandwith

alargenumberofsellers,asearchandmatchingenvironmentwoulddeliver

aratherlargedeparturefrom theoutcomeunderperfectcompetition(which

wouldprevailifthesearchcostswerezero). Thus,asmallsearchfriction

canhavealargeeffectonpriceoutcomes,anditwouldnotleadtoanyprice dispersionatall.

AheuristicexplanationofDiamond’sargumentisasfollows. Suppose

therearemanyidenticalbuyers,eachinsearchofoneunitofagood, and

thateachconsumeriswillingtobuythegood provideditcostsnomorethan

∗. Supposealsothattherearemanyidenticalsellers,whoeachcommittoa

priceatthebeginningofthegame. Thebuyersareperfectlyinformedabout

thepricedistribution,butateachpointintimeabuyeronlyknowstheprice

askedbyaparticularseller. Eachbuyermustthendecidewhethertobe

satis edwiththispriceorsearchmoretolearnthepriceofoneadditional

seller(sequentialsearch). Thissearch,however,only occursat acost,which

isassumedtobe xed. Itiseasytoseethatoptimalsearchpolicyinthis

contextinvolvesacutoffprice : thebuyerbuysthegood assoonasshe

encounters a price at or below . The precise level of this cutoff price

dependsontheparameters ofthemodel, suchasthe xedsearchcost, andon

theendogenouspricedistribution. Giventhatallconsumershaveidentical

searchcostsandfacethesamepricedistribution,itmustthenfollowthat

they have the same cutoff price. This immediately implies that all the

sellerswillcharge . However,ifthere isnodispersioninprices,itcannot

beoptimaltolearnmorethanoneprice. Thus,theuniqueequilibriumisone

inwhichallsellerschargethehighestpricebuyersarewillingtopay,i.e., ∗,

the“monopolyprice”. Putdifferently,no below ∗ canbeanequilibrium,

sinceanygiven rmwoulddeviateandchooseapriceeversoslightlyhigher

than ,byanamountsmallenoughthatitwouldnotbeworthwhilefor any

consumertosearchforanother rm. Thislogicworksnomatterhowsmall

thesearchcostis,aslongasitispositive.

Diamond’s surprising result inspired subsequent research on the exis-

tence of price and wage dispersion in search equilibrium where rms set 5

prices (wages) optimally. Some authors, for example Albrecht and Axell

(1984),developedmodelswheresomeheterogeneityacrossworkersand/or

rmsprevailedexante andwereabletoshowhowwagedispersionemerged

asanequilibriumoutcome. Otherauthorsmaintainedtheassumptionofex

ante identicalagentsbutconsideredalternativestosequentialsearch. An

importantcontributioninthisgenreisBurdettandJudd(1983),whore-

laxedtheassumptionofsequentialsearchandwereabletoprovethatprice

dispersionmayexistinequilibrium.

AdifferentresolutionoftheDiamondparadoxwasofferedinapaperby

BurdettandMortensen(1998). Theydevelopedamodelwithmonopsonistic

wagecompetitioninaneconomywith searchfrictionsandwereabletosolve

explicitly for the equilibrium wage distribution. Workers are identical ex

antebutindividualheterogeneityarisesexpost asworkersbecomeemployed

or unemployed. A key innovation was to allow for on-the-job search and

recognizethatreservationwagesamongemployedandunemployedsearchers

generallydiffer. Reservationwageheterogeneitycreatesatradeofffor rms

between“volume”and“margin”: high-wage rmsareabletoattractand

retainmoreworkersthanlow-wage rmsare,buttherentperworkerthat high-wage

rmscanextractisrelativelylow. Asintraditionalmodelsof

monopsony,anappropriatelysetminimumwagecanincreaseemployment andwelfare.

The literature on wage dispersion is nicely summarized in the recent

bookbyMortensen(2005). Onestrandofargumentsintheliteratureon

wagedispersionsuggeststhatmodelswithquantitativelylargewagedisper-

sionrequirethatworkerscansearchforotherjobswhileemployed;see,e.g.,

Burdett(1978)forapartial-equilibriumanalysis,Postel-VinayandRobin

(2002)foranequilibriummodel,andHornsteinetal.(2007)foraquantita-

tivecomparisonofmodelswithandwithouton-the-jobsearch. 2.2 Efficiency

Frictionalmarketsinvolvesearchexternalitiesthatmaynotbeinternalized

byagents. Consideramodelwheretheunemployedworkerdetermineshow

intensely to search for jobs. An increase in search effort implies a higher

individualprobabilityofbecomingemployed. However, therearetwoex-

ternalitieswhicharenottaken intoaccountby theindividualworker. On

theonehand, bysearchingharder,theindividualworkermakesotherun-

employedworkersworseoffbyreducingtheirjob ndingrates(“congestion

externality”). Ontheotherhand,bysearchingharder,theworkermakesem-

ployersbetteroffbyincreasingtherateatwhichtheycan lltheirvacancies 6

(“thickmarketexternality”). Congestionandthickmarketexternalitiesare

commoninsearchandmatchingmodelsanditisapriori unclearwhether

decentralizeddecisionsonsearchandwagesetting willinternalizethem.

In a series of contributions, Diamond examined the efficiency proper-

tiesofmarketswithfrictions(DiamondandMaskin,1979,1981;Diamond,

1982a). BuildingonanearlierpaperbyMortensen(1978)onefficientlabor

turnover, Diamond and Maskin (economics laureate in 2007) developed a

modelwhereindividualsmeetpairwiseandnegotiatecontractstocarryout

projects(DiamondandMaskin,1979). Thequalityofthematchisstochas-

ticandmatchedindividualshavetheoptiontokeepsearching(atacost)for

bettermatches. Aunilateralseparation(“breachofcontract”)occurswhen

apartnerhasfoundabettermatch. Theauthorsstudiedalternativecom-

pensationrulesforsuchbreachesofcontractandexaminedhowefficiency

is related to the properties of the meeting technology, i.e., the matching

function. Ingeneral,thecompensationrulesunderstudydonotresultin efficientoutcomes.

Diamond (1982a) considers a labor market with search on both sides

of the market albeit with a xed number of traders. Contacts between

traders—unemployedworkersand rmswithvacancies—aregovernedbya

matchingfunctionandwagesaredeterminedthroughNashbargaining. The

paperidenti essearchexternalitiesandis aprecursortomorerecentwork

oncongestionandthickmarketexternalities.

OtherimportantcontributionsinthisareaincludeMortensen(1982a,b)

andPissarides(1984a,b). Mortensen(1982a)speci esanexplicitmatching

technologyandtreatstheagents’searcheffortsasendogenous. Anefficient

outcomeisshowntorequirethatthematchsurplusshouldbecompletely

allocatedtothe“matchmaker”,i.e.,theagentwhoinitiatedthecontact.

However,thereisnomechanismtoachievethatoptimum;theequilibrium

isthusgenericallyinefficient. Mortensen(1982b)studiesdynamicgames,

including a patent race and a matching problem, where actions taken by

asingleagentaffectfutureoutcomesforother agents. Themainresultis

similartoMortensen(1982a): efficiencyrequiresthattheagentwhoiniti-

atedaneventshouldobtainthewholesurplus,lessacompensationpaidto

agentswhoareadverselyaffected. Theresultissometimesreferredtoas the“Mortensenprinciple”.

Pissarides(1984a)considersaneconomywithendogenoussearchinten-

sitiesonbothsidesofthemarketandshowsthatsearchintensitiesaregen-

erallytoolowandequilibriumunemploymenttoohigh. Pissarides(1984b)

analyzestheefficiencypropertiesofasearcheconomywithstochasticmatch

productivityand ndsthattherecanbetoolittleortoomuchjobrejection. 7

Pissaridesarguesthattoolittlejobrejectionisthemostplausibleoutcome,a

resultthatmaysuggestaroleforunemploymentbene tssoastoencourage

morerejectionsoflow-productivitymatches.

Thesestudiesonefficiency byDiamond,MortensenandPissaridesare

forerunnerstothecomprehensivetreatmentofsearchexternalitiesinmatch-

ingmodelsprovidedbyHosios(1990). Theso-calledHosiosconditionstates

that the equilibrium outcome is constrained efficient if the elasticity of

matching with respect to unemployment is equal to the worker’s relative

bargaining power.1 With Nash bargaining over wages, there is no reason

whytheHosiosconditionshouldapply. Recentworkonefficiencyproper-

tiesofsearchequilibriahasconsideredalternativestoNashbargaining. One

strandofliterature–competitivesearchequilibriumtheory–hasshownhow

theHosios conditioncanariseendogenously;see,e.g.,Moen(1997). In one

versionofthesemodels, rmspostwagessoastoattractmoreapplicants.

Jobseekers allocatethemselvesacross rms,whilerecognizingthatahigher

offeredwage isassociatedwitha lowerprobabilityofgettinghired sincea

higherwageleadstoalongerqueueofseekers. Inequilibrium,workersare

indifferentaboutwhich rmtoconsider.

Arelated strandofthesearchliteraturebeginswithLucasandPrescott

(1974),whodevelopan“islandmodel”ofsearch. Oneachisland,markets

arecompetitive(withmany rmscompetingformanyworkers)andthere

arenosearchcosts,butworkersmaysearchamongislandsandbe imper-

fectlyinformedaboutconditionsonspeci cislands. Asformulated,these

modelsdonotfeatureanyexternalitieseitheranddecentralizedequilibria areefficient. 2.3 Coordinationfailures

InDiamond(1982b),itisarguedthatsearchexternalitiescanevengenerate

macroeconomiccoordinationproblems. Inordertomakeacomprehensive

logicalargument,Diamondconstructedanabstractmodelthatallowedfor

carefulexaminationoftheseissues. Variantsandfurtherdevelopmentsof

thismodelhavehadalargeimpactinseveralareasofeconomics,notonlyfor

thestudy ofcoordinationproblemsbutalsoasaprototypewayofstudying

equilibriawithsearchandmatching.

1 Using a common functional form for the matching function, the relevant elasticity,

denoted ,isconstant. Intermsofthenotationofthelabor-marketmodelinSection3

below,thematchingfunctioncanbewrittenas ( ) = 1− ,where and denote

unemploymentandvacancies. TheHosioscondition saysthat = , where isameasure

oftheworker’srelativebargainingpower. 8

Consideracontinuumofrisk-neutralagentswhoderiveutilityfromcon-

suminganindivisiblegoodandwhodiscountutilityatrate ;timeiscon- tinuous,and the

owutilityofconsuming agoodis . Consumersneedto

trade: theyeachproduceagood,buttheydonotconsumethegoodthey

produceandthereforeneedto ndatradingpartnerin ordertoexchange

goods. Forsimplicity,Diamondassumesthataconsumeriswillingtocon-

sumeanygoodotherthanhisown. Productionofgoodsoccursrandomly

andwitharandomcost structure. Theopportunitytoproduceagoodar-

rivesaccordingtoaPoissonprocessata owprobabilityrate . Whena

production possibility appears, the cost of production is , with the cost

drawn from a distribution function ( ). The consumer can then choose

to produce or not depending on (i) how costly it is and (ii) the value of

beingendowedwithagoodthatcanbeusedfortrade,which dependson

how easy it is to encounter other consumers endowed with goods. Thus,

theproduction-consumptionstructureassumedhereisanabstractwayof

capturinggainsfrombilateraltrade;thoughexpressedaveryparticularway

inthemodel,theideaandapplicabilityoftheargumentseemquitegeneral.

Bilateralmeetings,however, donotoccurwithoutfrictionsinDiamond’s

model. Letthenumberofconsumersendowedwith agood,andthussearch-

ingfortradingpartners,bedenoted

(for“searchers”). Wefocusonthe

casewheretheeconomyisinasteadystate,sothat isconstant. Letthe

owprobabilityofmeetingatradingpartnerbe ( ), where (0) = 0 and 0( )

0. The greater the number of agents searching for partners, the

higheristheprobabilityof ndingoneforanygivenagent.

Thepoolofsearchersisdiminishedateachpointintimebythenumber

of traders who nd partners and thus can consume, ( ). The pool is

increasedbythenumberofagentswhohaveaproductionopportunityand who decide to produce: (1− )

( ∗), i.e., the number of non-searchers

timestheprobabilityofaproductionopportunitytimestheprobabilitythat

theproductioncostisbelowthecutoffcost, ∗. Flowequilibriumimplies: ( ) = (1− ) ( ∗) (1)

Thecutoff costistobedeterminedinequilibrium. Productionoppor- tunitiesareacceptedfor ≤ ∗ andrejectedfor ∗. Todeterminethe

cutoffcost,considerthe owutilityofasearchingconsumerwhichisgiven as = ( )[ − ( − )] (2) where

is the expected lifetime utility of a searching agent and the

expected lifetime utility of an agent who does not search. The searching 9

agent meets a trading partner at the rate ( ), consumes and switches

fromsearchertonon-searcher,therebyexperiencingalossinlifetimeutility givenby −

. The owutilityofanon-traderreads = maxZ ∗(− + − ) ( ) (3) 0 ∗

Thenon-searcher ndsaproductionopportunityattherate anddecides

whether or not to pay the cost , thereby experiencing a capital gain of − .

Thesteadystateofthemodelisstraightforwardtoanalyze. Clearly,it

mustbethatthecutoffcostsatis es ∗ = − . Itisthuspossibleto subtract(3)from (2)toobtain Z ∗ ( ) − ∗ ( ∗). (4) ∗ = ( )( − ∗)+ 0

Equation(4)andthesteady-stateconditiongivenby(1)determine ∗

and . Theequationscanbedepictedastwopositivelyslopedrelationships inthe( ∗

) space. Ingeneral,multipleequilibriaarepossibleandequilibria

involvingahigherlevelofeconomicactivityyieldhigherwelfare. Thus,there

ispotentiallyarolefor“demandmanagement”,i.e.,forgovernmentpolicy

inducinghigheractivity sothattheeconomycouldmovefromabadtoa goodsteadystate.

Literally,aproofthatagoodsteadystateisbetterthanabadsteady

stateisnota proofofinefficiency. Themovefromabadsteadystatetoa

goodsteadystatewouldrequireatransitionperiodwherebyagentswould

rststartproducingonlytobeabletotradelater. Initiallyitwouldbehard

to ndtradingpartnerssincethereareveryfewofthemduetothelowlevel

ofproduction. Inalaterpaper,DiamondandFudenberg(1989)analyzed

themodelfromthisperspectiveandindeedestablishedinefficiencyaswellas

entirely“expectations-driven”equilibriummultiplicity. Theyalso demon-

strated that this economy could feature business-cycle-like uctuations in

outputwithout uctuationsinthefundamentalparameters.

Akeyingredient–subjecttomuchdiscussionandempiricalevaluation–

inDiamond’ssettingistheassumptionthat ( ) isincreasing: thelarger

thenumberoftradersinthemarket,thehigherthemeetingrates. Thatis,

themoretradersthereare,thelowerarethesearchfrictions. Thisassump-

tion,emphasizingtheimportanceofscale, isusuallyreferredtoasoneof

“increasingreturnstoscale”. Itisanopenquestioninanygiventrading 10

contextwhetherthisassumptionisappropriate. Forlabormarkets,many

argue that constant returns–in which case multiple steady states cannot

coexist–describerealitybetter(see,e.g.,PetrongoloandPissarides,2001).

Themodelsetuphasalsobeenusedinothercontexts,seee.g.,Duffieetal.

(2005)for anapplicationto nancialmarkets.

Diamond’s(1982b)articleisoftenviewedasde ninganewapproach,

basedonacarefulanalysisusingmicroeconomicfoundations,toanalyzing

someofthecentralthemesofKeynes’sbusiness-cycletheory.2 Coordina-

tionproblemswereofcentralimportanceinKeynes’swritings;theycanbe

viewedasawayofallowingfor“sentiments”toin uencetheeconomy,such

asKeynes’swell-knownparableofthe“animalspirits”ofinvestors. Ifin-

vestorssensethatotherinvestorswillbeactiveandproduce,theyproduce

too,thereby leadingtohigheconomicactivity. Butanotherequilibriumin

thesameeconomyinvolveslowactivity. 3 Equilibriumunemployment

Unemploymentsuggests“missingopportunities”fromasocietalperspective

and potential inefficiency of market outcomes. Through a long series of

systematicandpartly overlapping contributions,Diamond,Mortensen and

Pissarideshavebuiltafoundationfortheanalysisoflabormarketsbased

onsearchandmatchingfrictions. Thiswork,whichbeganwithMortensen

(1970a,b), has fundamentally in uenced the way economists and policy-

makers approach the subject of unemployment. Their canonical model–

the DMP model–has more broadly become a cornerstone of macroeco-

nomicanalysisofthelabormarket. Key contributionsareDiamond(1981,

1982a,b),Mortensen (1982a,b),Pissarides(1979, 1984a,b,1985),andMor-

tensenandPissarides(1994). Pissarides’sin uentialmonograph(1990/2000)

providessynthesisandextensions.3

TheDMPmodelisatheoreticalframeworkwithacommoncoreanda

rangeofspeci cmodelsthatdealwithparticularissuesandinvokealterna-

tiveassumptions. Wagesareusuallydeterminedviabargainingbetweenthe

workerandthe rm. Frictionsin themarketimplythattherearerentsto

besharedonceaworkeranda rmhaveestablishedcontact. Rentsaretyp-

2 Diamond’sWickselllectures(Diamond,1984)includesabroaddiscussionofthesearch

equilibriumapproachtothemicrofoundationsofmacroeconomics.

3 MortensenandPissarides(1999b,c)reviewthesearchandmatchingmodelwithappli-

cationstolaboreconomicsandmacroeconomics. Arecentcomprehensivesurveyofsearch

modelsofthelabormarketisprovided byRogersonetal. (2005). 11

icallysharedthroughtheNashsolution,butthebasicmodeliscompatible withotherwage-settingrules.

AnimportantconceptintheDMPmodelistheso-calledmatchingfunc-

tionthatrelatesthe owofnewhirestothetwokeyinputsinthematching

process: thenumberofunemployedjobsearchersandthenumberofjobva-

cancies. Thisconcepthasallowedresearcherstoincorporatesearchfrictions

intomacromodelswithouthavingtospecifythecomplexdetailsofthose

frictions(suchasgeographicalorinformationaldetail). 3.1 Abenchmarkmodel

The benchmark labor-market model that emerged from the work of Dia-

mond,MortensenandPissaridescanbedescribed inarelativelycompact

way. Inthefollowing,asimpleversionofthesetupdevelopedinPissarides

(1985) is described. This setup, which does not address wage dispersion,

canperhapsbeviewedasthecanonicalequilibriummodelofsearchunem-

ployment. Albeitsimple,themodelis exibleenoughtobeusefulforboth

confrontingdataandanalyzingpolicyissues. 3.1.1 Labor-market ows

Consider a labor market in a steady state with a xed number of labor force participants,

, who are either employed or unemployed. Time is

continuous and agents have in nite time horizons. Jobs are destroyed at

theexogenousrate ;allemployedworkersthuslosetheirjobsandenter

unemployment at the same rate. Unemployed workers enter employment at the rate

which is endogenously determined. Frictions in the labor

marketaresummarizedbyamatchingfunctionoftheform = ( ), where

isthenumberofunemployedworkersand thenumber ofjob

vacancies. Thematchingfunctionistakenasincreasinginbotharguments,

concaveandexhibitingconstantreturnstoscale. Unemployedworkers nd jobs at the rate = ( ) = (1 ) = ( ), where ≡

is a measure of labor market tightness. Firms ll vacancies at the rate = ( ) = ( 1)= ( ). Obviously, 0( ) 0, 0( ) 0 and ( )=

( ). Thetighterthelabormarket,theeasieritisforworkersto

ndajob,andthemoredifficultfor rmsto llavacancy.

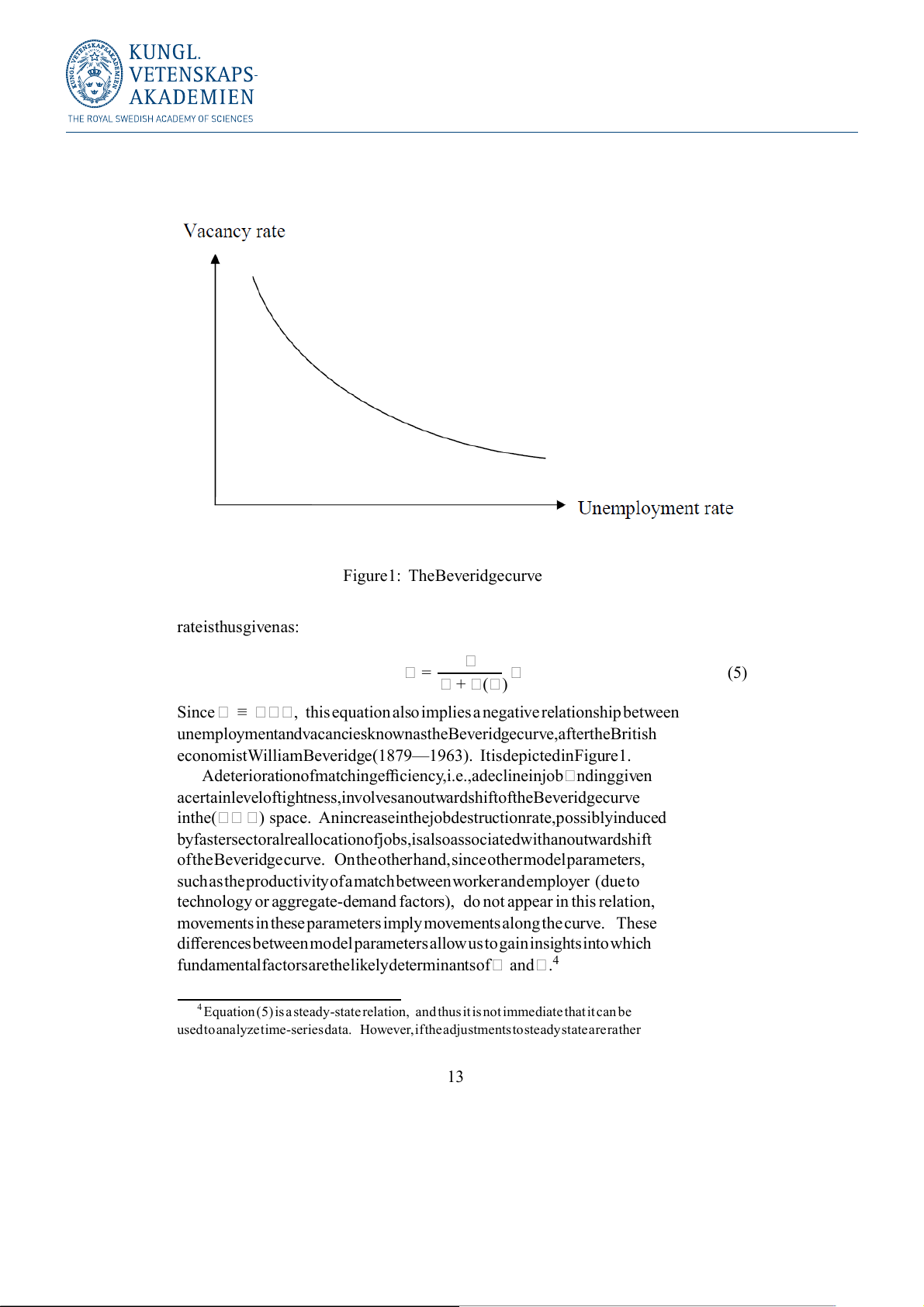

Asteadystateentails“equilibrium”inthelabormarketinthesensethat

theunemploymentrateisunchangingovertime. Thisoccurswhenthein ow

fromemploymentintounemployment, (1− ) , equalstheout owfrom unemployment to employment, ( )

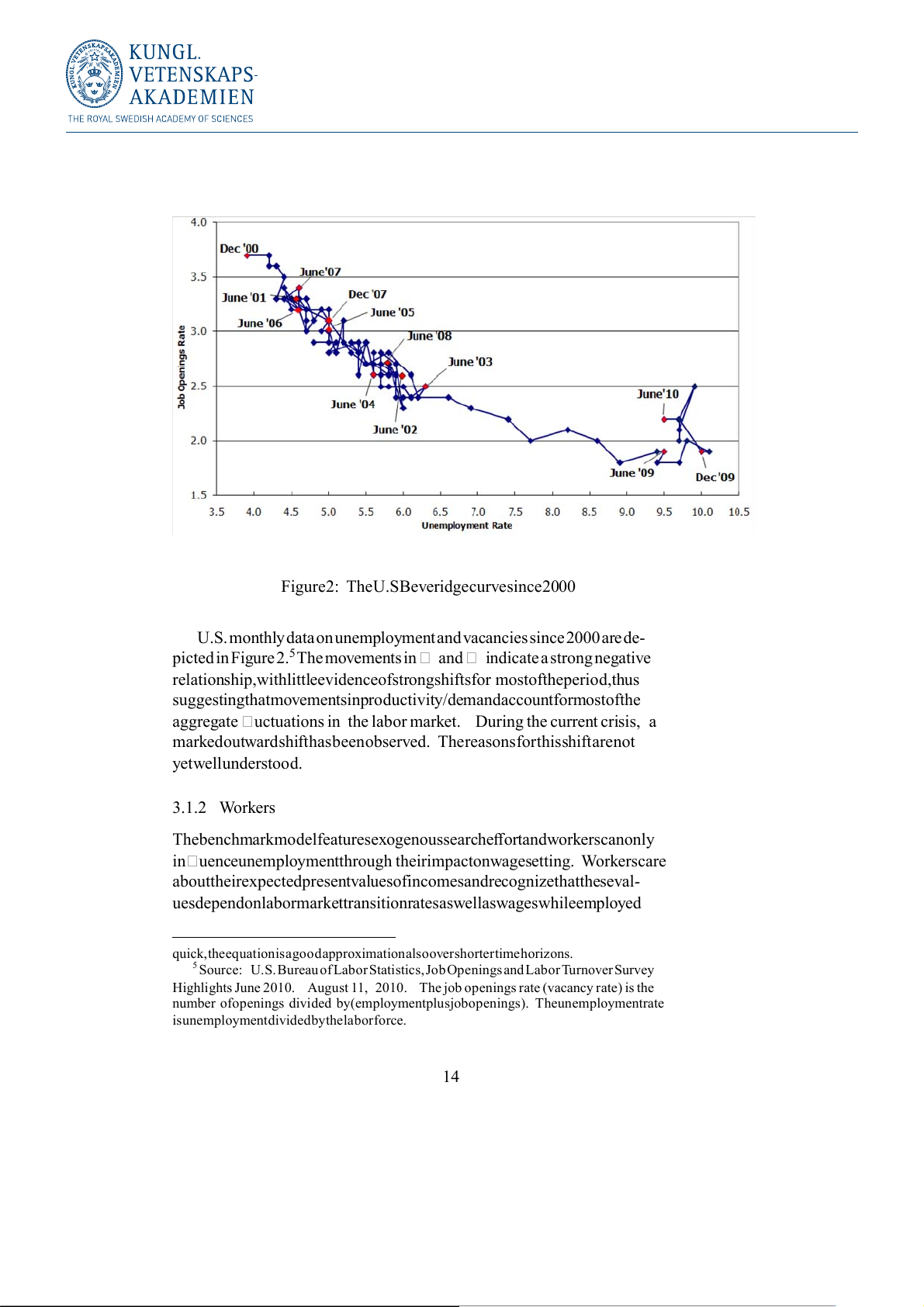

. The steady-state unemployment 12 Figure1: TheBeveridgecurve rateisthusgivenas: = (5) + ( ) Since ≡

, thisequationalsoimpliesanegativerelationshipbetween

unemploymentandvacanciesknownastheBeveridgecurve,aftertheBritish

economistWilliamBeveridge(1879—1963). ItisdepictedinFigure1.

Adeteriorationofmatchingefficiency,i.e.,adeclineinjob ndinggiven

acertainleveloftightness,involvesanoutwardshiftoftheBeveridgecurve inthe(

) space. Anincreaseinthejobdestructionrate,possiblyinduced

byfastersectoralreallocationofjobs,isalsoassociatedwithanoutwardshift

oftheBeveridgecurve. Ontheotherhand,sinceothermodelparameters,

suchastheproductivityofamatchbetweenworkerandemployer (dueto

technology or aggregate-demand factors), do not appear in this relation,

movementsintheseparametersimplymovementsalongthecurve. These

differencesbetweenmodelparametersallowustogaininsightsintowhich

fundamentalfactorsarethelikelydeterminantsof and .4

4 Equation(5)isasteady-staterelation, andthusitisnotimmediatethatitcanbe

usedtoanalyzetime-seriesdata. However,iftheadjustmentstosteadystatearerather 13

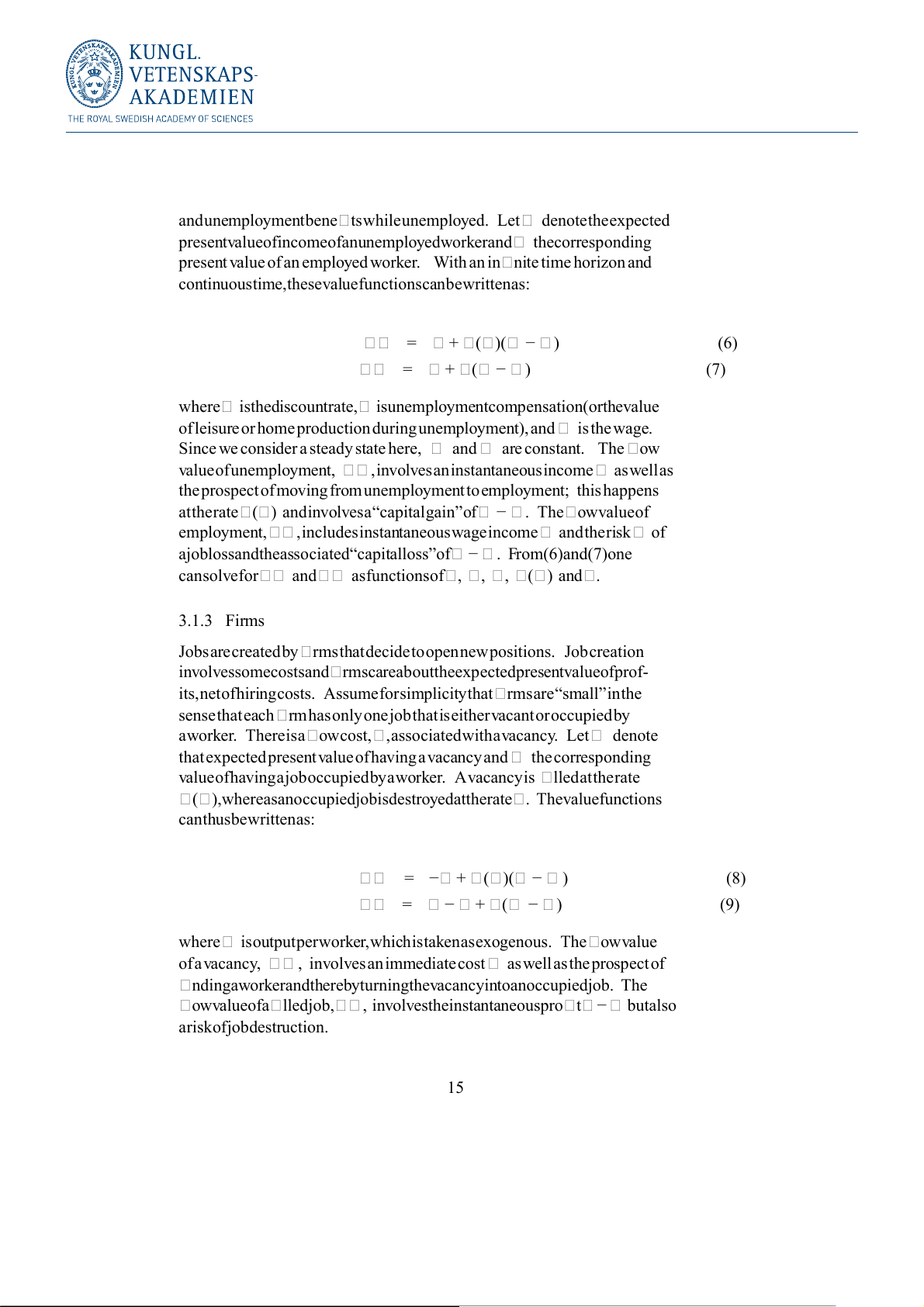

Figure2: TheU.SBeveridgecurvesince2000

U.S.monthlydataonunemploymentandvacanciessince2000arede-

pictedinFigure2.5Themovementsin and indicateastrongnegative

relationship,withlittleevidenceofstrongshiftsfor mostoftheperiod,thus

suggestingthatmovementsinproductivity/demandaccountformostofthe

aggregate uctuations in the labor market. During the current crisis, a

markedoutwardshifthasbeenobserved. Thereasonsforthisshiftarenot yetwellunderstood. 3.1.2 Workers

Thebenchmarkmodelfeaturesexogenoussearcheffortandworkerscanonly

in uenceunemploymentthrough theirimpactonwagesetting. Workerscare

abouttheirexpectedpresentvaluesofincomesandrecognizethattheseval-

uesdependonlabormarkettransitionratesaswellaswageswhileemployed

quick,theequationisagoodapproximationalsoovershortertimehorizons.

5 Source: U.S.BureauofLaborStatistics,JobOpeningsandLaborTurnoverSurvey

Highlights June 2010. August 11, 2010. The job openings rate (vacancy rate) is the

number ofopenings divided by(employmentplusjobopenings). Theunemploymentrate

isunemploymentdividedbythelaborforce. 14

andunemploymentbene tswhileunemployed. Let denotetheexpected

presentvalueofincomeofanunemployedworkerand thecorresponding

present value of an employed worker. With an in nite time horizon and

continuoustime,thesevaluefunctionscanbewrittenas: = + ( )( − ) (6) = + ( − ) (7) where

isthediscountrate, isunemploymentcompensation(orthevalue

ofleisureorhomeproductionduringunemployment),and isthewage.

Since we consider a steady state here, and are constant. The ow valueofunemployment, ,involvesaninstantaneousincome aswellas

theprospectofmovingfromunemploymenttoemployment; thishappens

attherate ( ) andinvolvesa“capitalgain”of − . The owvalueof employment,

,includesinstantaneouswageincome andtherisk of

ajoblossandtheassociated“capitalloss”of − . From(6)and(7)one cansolvefor and asfunctionsof , , , ( ) and . 3.1.3 Firms

Jobsarecreatedby rmsthatdecidetoopennewpositions. Jobcreation

involvessomecostsand rmscareabouttheexpectedpresentvalueofprof-

its,netofhiringcosts. Assumeforsimplicitythat rmsare“small”inthe

sensethateach rmhasonlyonejobthatiseithervacantoroccupiedby

aworker. Thereisa owcost, ,associatedwithavacancy. Let denote

thatexpectedpresentvalueofhavingavacancyand thecorresponding

valueofhavingajoboccupiedbyaworker. Avacancyis lledattherate

( ),whereasanoccupiedjobisdestroyedattherate . Thevaluefunctions canthusbewrittenas: = − + ( )( − ) (8) = − + ( − ) (9) where

isoutputperworker,whichistakenasexogenous. The owvalue ofavacancy, , involvesanimmediatecost aswellastheprospectof

ndingaworkerandtherebyturningthevacancyintoanoccupiedjob. The owvalueofa lledjob,

, involvestheinstantaneouspro t − butalso ariskofjobdestruction. 15 Freeentryofvacanciesimplies =0 inequilibrium: rmsopenvacan-

ciesaslong asitispro tabletodoso. Byimposingthefree-entrycondition

on eqs. (8) and (9), one obtains the key demand-side relationship of the model: ( + ) − = (10) ( )

This free-entry condition implies a negative relationship between the

wageandlabormarkettightness. Thetighterthelabormarket,themore

costlyitistorecruitnewworkers. Thishastobeoffsetbylowerwagessoas tomaintainzeropro ts. Notethat mustholdbecauseofhiringcosts,

0. Inequilibrium,theexcessofthemarginalproductoflaboroverthe

wagecostisequaltotheexpectedcapitalizedvalueofthevacancycost. The

incentivestocreatevacanciesarereducedbyahigherreal interestrate,a

higherjobdestructionrateandahighervacancycost. Vacancycreationis

encouragedbyimprovedmatchingefficiencythatexogenouslyincreasesthe

rateatwhichthe rmmeetsjobsearchers. 3.1.4 Wagebargaining

Sincethelabormarketischaracterizedbyfrictionsandbilateralmeetings,

thestandardwagedeterminationmechanism doesnotcomeintoplay. So

how are wages determined? The main approach that has been used in

theliteratureassumesthatthereisbargainingbetween theemployerand

theworker. So supposethatwagesaresetthroughindividualworker- rm

bargains andthattheNashsolutionapplies,i.e., max Ω=[ ( ) − ] [ ( ) − ]1− where

isameasureoftheworker’srelativebargainingpower, ∈ (0 1).

( ) and ( ) representpresentvaluesassociatedwithaparticularwage

inthisbilateralbargain (tobedistinguishedfromthewageusedinother matches),i.e., ( ) = + [ − ( )] ( ) = + [ − ( )]

Thevalueofunemploymentisindependentof andisobtainedfromeqs.

(6)and(7). NotethatthethreatpointsintheNashbargainaretakentobe 16

and ,i.e.,whattheworkerandthe rmwouldreceiveuponseparation fromeachother.

Theoutcome ofthismaximizationisasurplus-sharingruleoftheform: ( ) − = [ ( ) − + ( ) − ] (11)

Thewageissetsoastogivetheworkerafraction ofthetotalsurplus

fromawageagreement. Eq.(11)canberewritteninseveralwayssoasto

yieldawageequation,i.e.,thebargainedwageasafunctionoflabormarket

tightness andtheparametersoftheproblem. Auseful partial-equilibrium

wageequationexpressesthewageasaweightedaverageoflaborproductivity andthe owvalueofunemployment:6 = + (1− ) (12)

Itispossibletogoonestepfurthertoobtainthefollowing:7 = (1− ) + ( + ) (13)

Thisexpressionhastheintuitivepropertythatthebargainedwageisan

increasingfunctionofunemploymentbene ts,laborproductivityandlabor markettightness. 3.1.5 Equilibrium

Theoverallsteady-stateequilibriumisnowcharacterizedbyeqs. (5),(10)

and (13). Eqs. (10) and (13) determine and andtheunemployment

ratefollowsfrom (5). Thevacancyrateisobtainedbyusingthefactthat =

. Theequilibriumunemploymentrateisdeterminedby , , , , ,

aswellasbytheparametersofthematchingfunction. Itispossible,by

variablesubstitution,toreducethesetofequationstooneequationinone

unknown: labor-markettightness. 3.1.6

Comparativestatics,policyanalysis,andmodelevaluation

Giventhatthemodelcanbeanalyzedinsuchasimpleway, comparative

staticanalysisisstraightforward. Considerforexampleanincreaseinun- 6 Use ( ) = + [ − ( )] and ( ) = − + [ − ( )],substitutethese

expressionsinto(11)andimposethefree-entrycondition = 0.

7 Imposefreeentryin(8)andobtain = ( ). Use = ( ) in(11)toobtaina relationshipbetween − and

( ). Substitute theexpressioninto(6)toeliminate −

andsubstitutethe resultingexpressionfor backinto(12). 17

employmentbene ts. Thisraisesthevalueofunemploymentand reduces

the worker’s gain from a wage agreement; the resulting increase in wage

pressureleadstoadeclineinjobcreation,higherunemploymentandhigher

realwages. Ahigherrealinterestratehasanadverseimpactonjobcreation

whichleadstofewervacancies,higherunemploymentandlowerrealwages.

It also easy to verify that unemployment increases if there is an increase

inthevacancycost, thejobdestructionrate,orthe worker’srelativebar-

gainingpower. Thematchingfunctionentersviatworoutes: ( ) ineq.

(5)–the Beveridge curve–and

( ) in eq. (10), the free-entry condition.

Improvements in the matching technology reduce unemployment directly

(holdingthenumberofvacanciesconstant)aswellasindirectly(by effec-

tivelyreducinghiringcostsandtherebyencouragingjobcreation)andreal wagesincrease.

Theimpactofproductivityonunemploymentisintriguing. Inthebench-

markmodelasspelledoutabove,ahigherlevelofproductivityleadstolower

unemployment;thepositiveimpactonjobcreationdominatestheoffsetting

effectarisingfromhigherwagepressure. Arguably,thisresultisreasonable

fortheshortrunbutnotforthelongrun,sincethelevelofproductivityisa

positivelytrendedvariablewhereasunemploymentdoesnotappeartohave

atrendoveralongenoughperiodintime. Amodelabletoreplicatethe

stylizedfactsofbalancedgrowthshouldthusfeatureincreasingrealwages

but constant unemployment. Two slight modi cations of the benchmark

modelaresufficientforachievingthatgoal. Thespeci cationsofvacancy

costsandunemploymentbene ts,possiblyincluding thevalueofhomepro-

duction, are crucial. Suppose that unemployment bene ts are “indexed”

torealwages(orproductivity)andthehiringcostgrowsintandemwith

realwages(orproductivity). Thenrealwageswillberesponsivetogeneral

productivityimprovementsandthemodelwould,infact,yieldpredictions

consistentwithstylizedbalancedgrowthfacts.8

The model provides a useful framework for analyses of various policy

issues. The effects of hiring and ring costs are two pertinent examples.

Theimpactof ringcostsdependsonwhetherthecostsinvolvetransfersto

workerswhoarelaidofforappearas“redtape”costsperhapsassociated

withstringentemploymentprotectionrules. Layoffcoststhattakethe form

8 The modi cationsofthe benchmarkmodelcanberationalized invariousways. Un-

employmentbene tsareinpracticetypicallyindexedtowagesandrecruitmentactivities

arelaborintensiveactivities. Moregenerally,theworker’simputedincomeduringunem-

ploymentcanberegardedasproportionaltohispermanentincome, i.e., . SeePissarides

(2000),chapter3,foradiscussionofsome oftheissuesinvolved. 18

ofseverancepaytolaid-offworkersdonotalterthetotalsurplusofamatch

andwillnotaffectjobcreationandunemployment. Redtapecostsreduce

thesurplusofamatchandleadtolowerjobcreation.

There is also a large literature that assesses the model quantitatively,

usingavarietyofevaluationmethodsanddifferentdatasets. Thedevel-

opment of search and matching theory has led to a large empirical liter-

ature. The early microeconomic models of job search initiated new data

collection efforts focusing on individual labor market transitions, in par-

ticular transitions from unemployment to employment. The more recent

macroeconomics-oriented search and matching theory has been developed

in parallel with improved data availability on worker ows and job ows (seeSection3.3below).

Themicroeconomicsearchmodelshavestimulated numerousempirical

studiesofthedeterminantsofunemploymentduration. Themethodological

literatureoneconometricdurationanalysishasexpandedsubstantiallyover

thepastcoupleofdecades, adevelopmentthatistoalargeextentdriven

bythegrowthandimpactofmicroeconomicsearchtheory. Theeffectsof

unemploymentbene tsonindividualunemploymentdurationconstitutethe

mostwidelyresearchedissueinthisstrandofliterature. Theearlypapers,

datingback tothelate1970s,typicallyidenti edtheimpactbyexploiting

cross-sectionalbene tvariationacrossindividuals. Morerecentstudieshave

exploitedinformationfrompolicyreformsandquasi-experiments. The em-

piricalstudiesgenerally suggestthatmoregenerousbene tstendtoincrease

thedurationofunemployment. AkeytheoreticalpredictionfromMortensen

(1977)–thattheexitratefromunemploymentincreasesastheworker ap-

proachesbene texhaustion–hasbeencorroboratedinaverylargenumber ofstudiesfrommanycountries.

Althoughinformationabouthowindividualsrespondtobene tchanges

isuseful,itcapturesonlyapartialequilibriumrelationshipsince rmbehav-

iorisignored. Theequilibriumoutcomewillalmostcertainlydifferquan-

titatively and conceivably also qualitatively from the partial equilibrium

relationship. Moreover, there are many policies, such as minimum wages

oremploymentsubsidies,thatcannotbeanalyzedwithinthepartialequi-

libriumframework. Theseconcernshaveinitiatedanumberofattemptsto

estimatemodelsofequilibriumsearcheconometricallyusingmicrodata. A

seminalpaperisEcksteinandWolpin(1990),whoestimatedtheAlbrecht

andAxell(1984)model. AmorerecentstudyisvandenBergandRidder

(1998),whoestimatedanextendedversionoftheBurdett andMortensen

(1998) model. Mortensen (2005) includes a comprehensive discussion of

wagedifferencesinDenmarkfromtheperspectiveofsearchandmatching 19